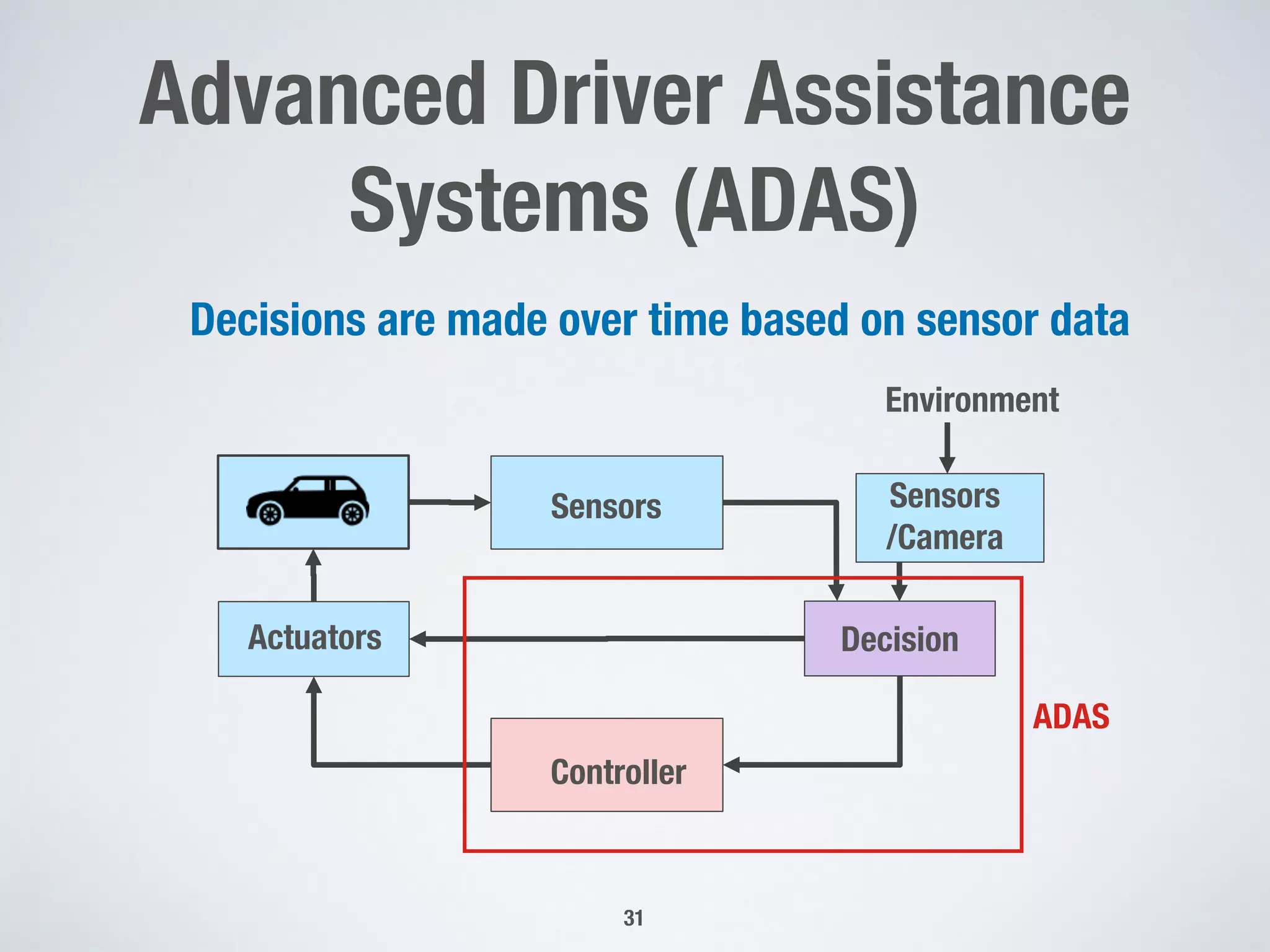

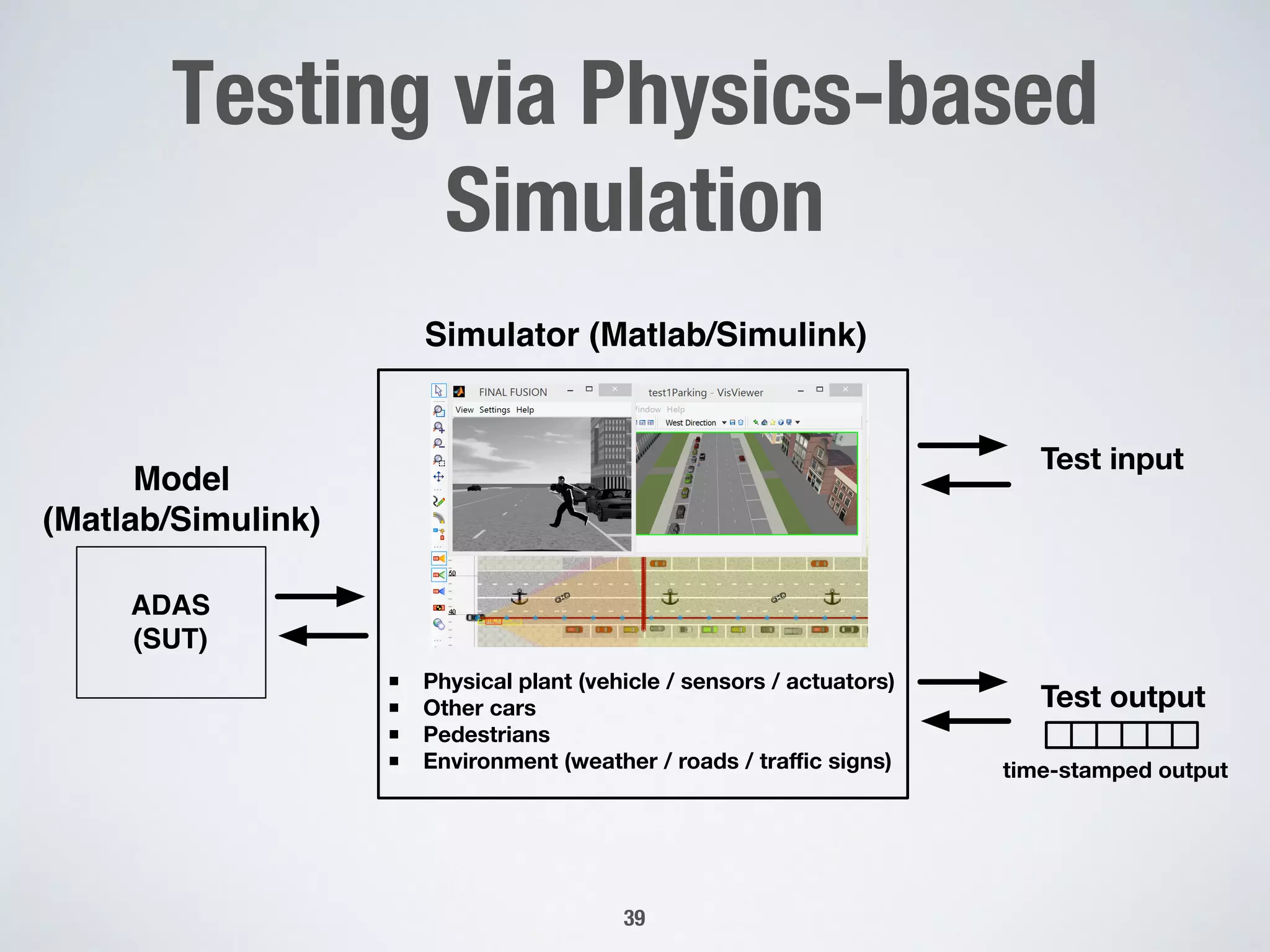

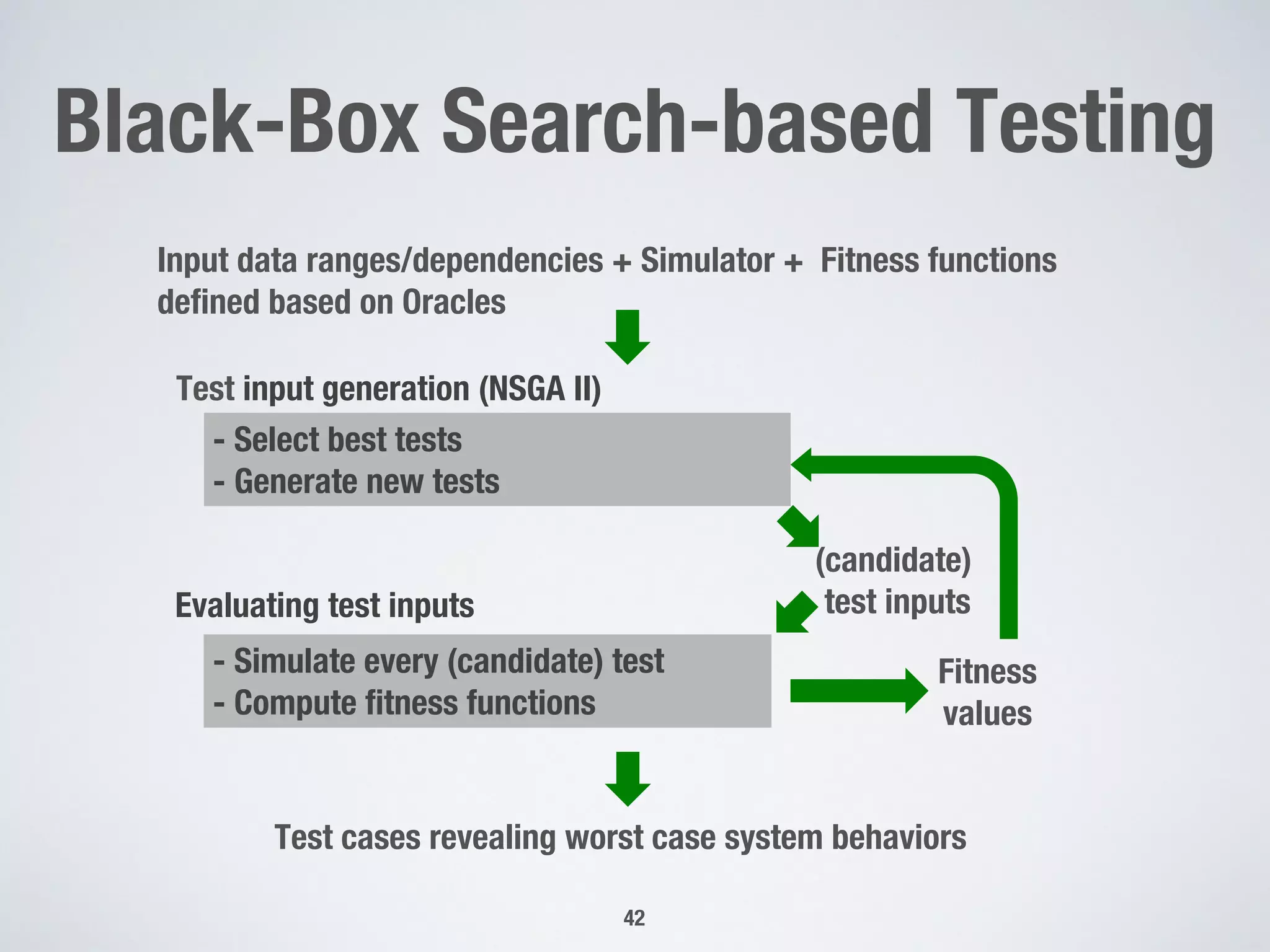

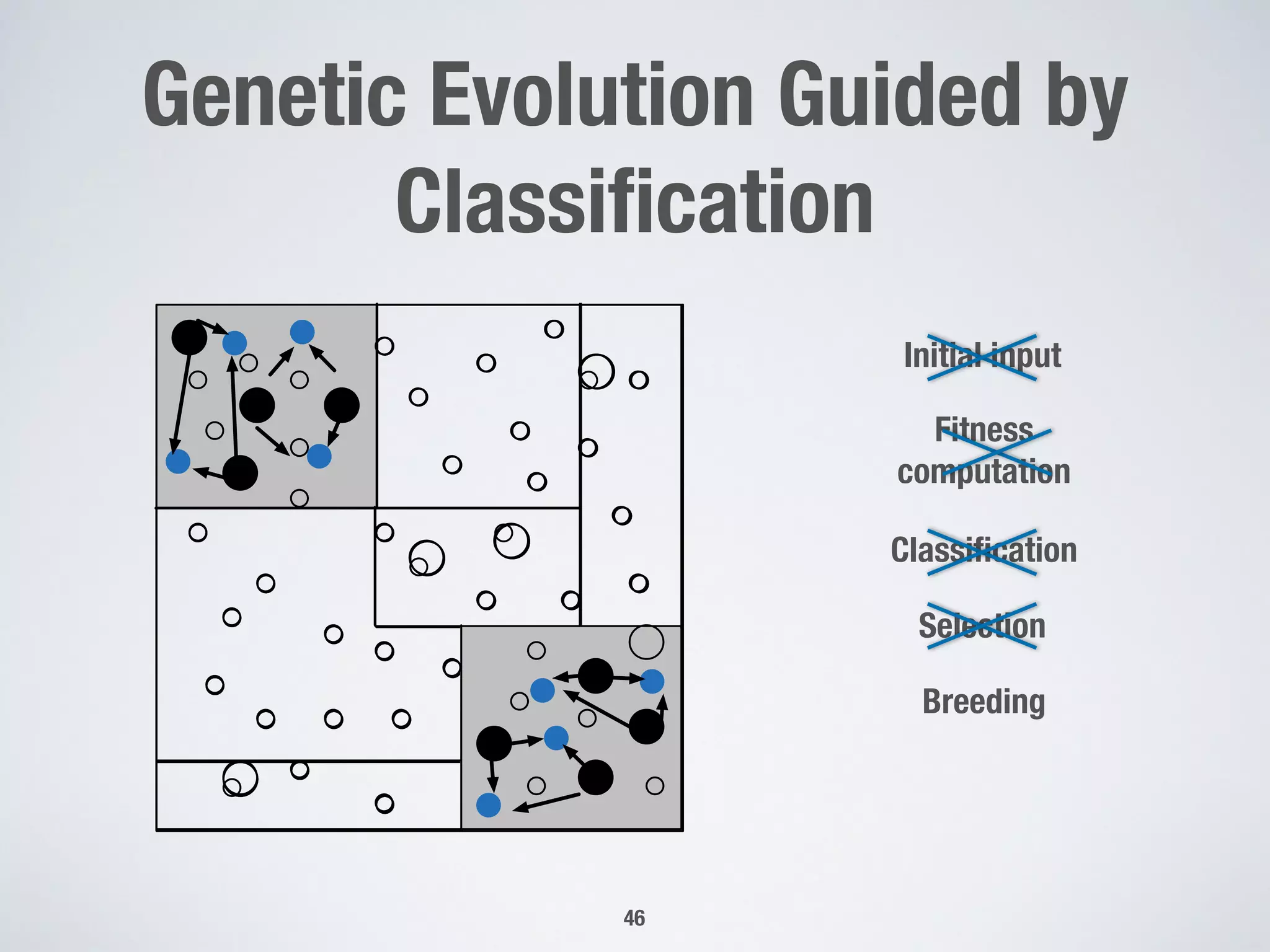

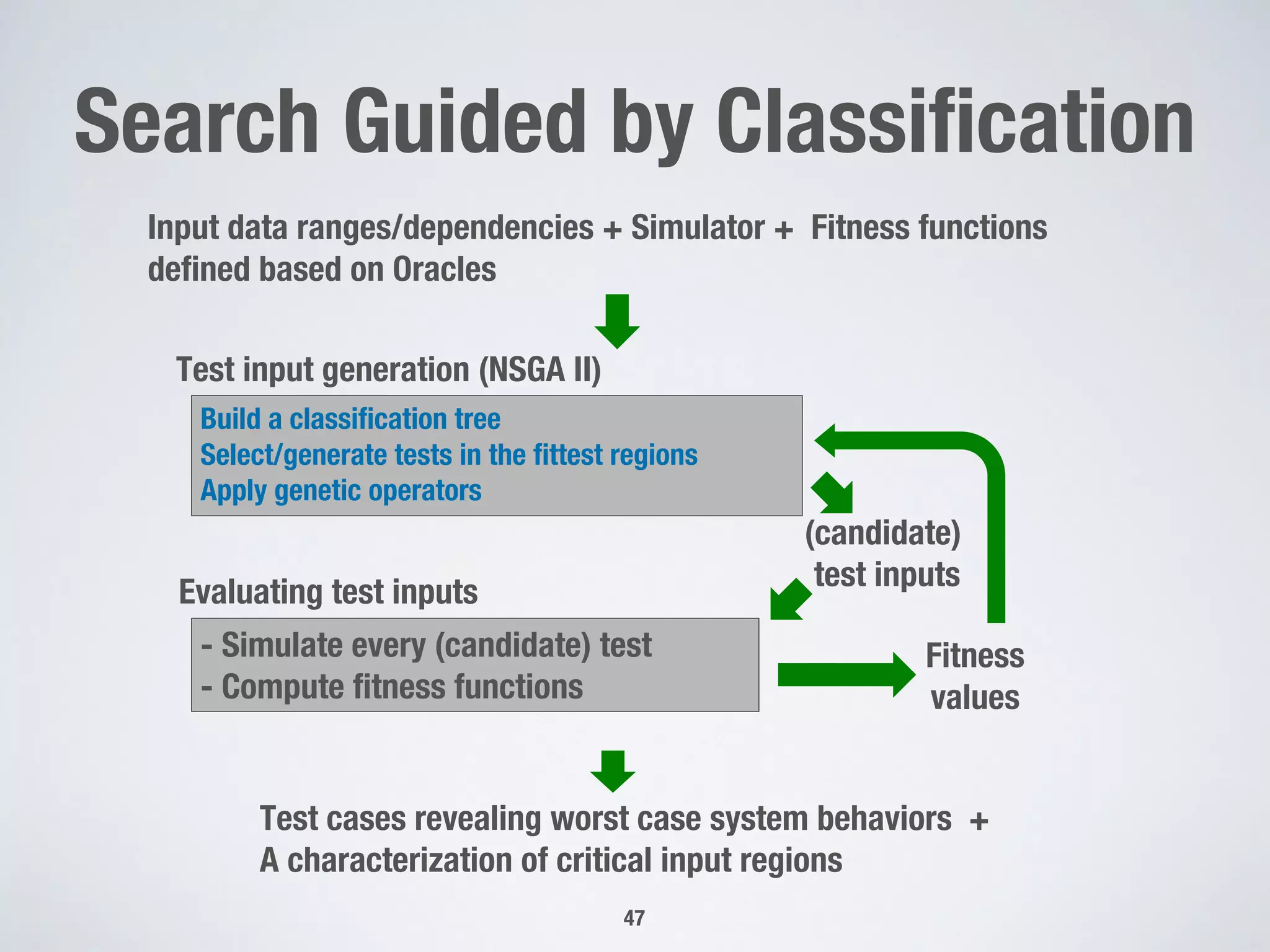

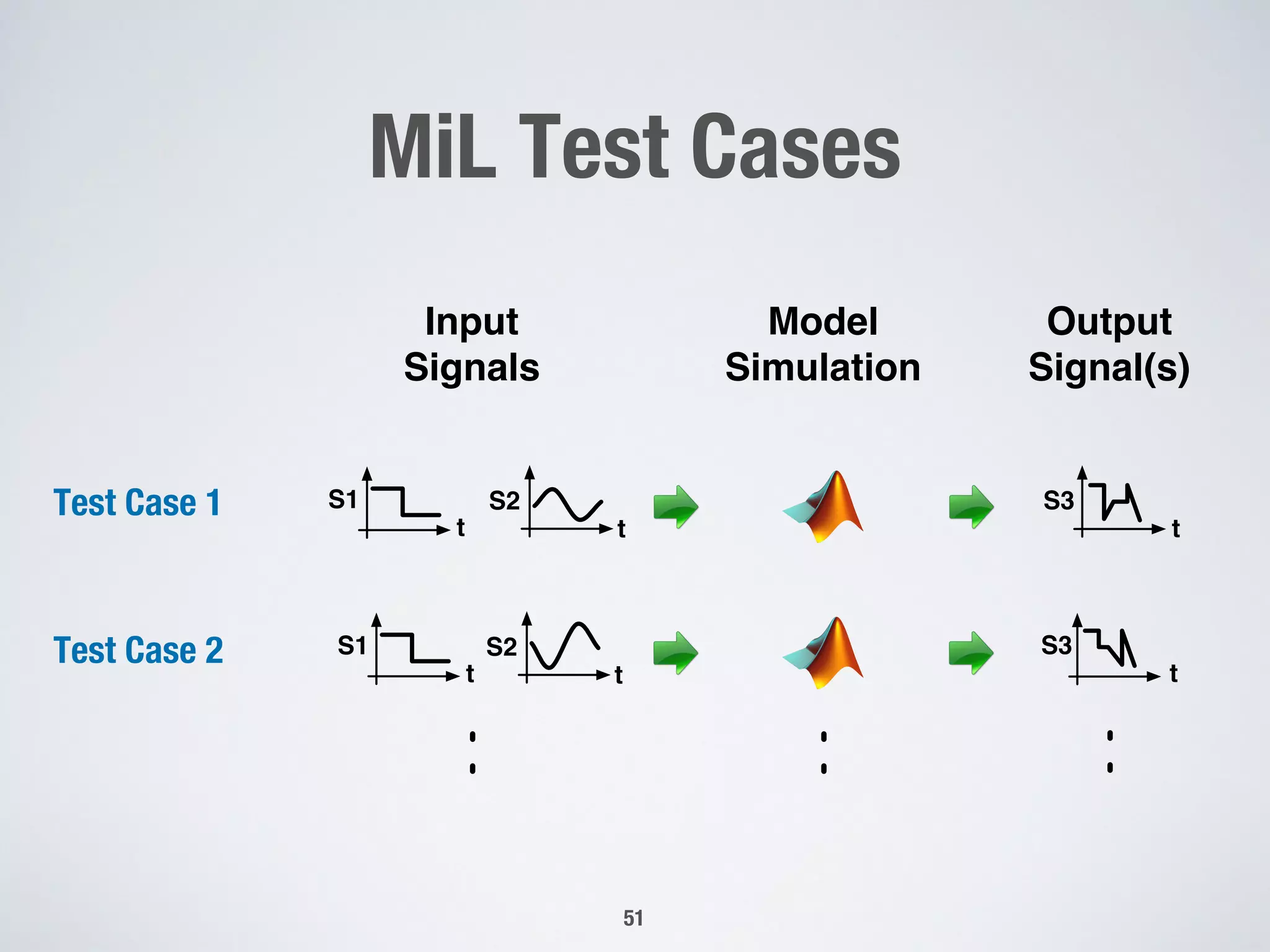

This document discusses techniques for testing advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) through physics-based simulation. It faces challenges due to the large, complex, and multidimensional test input space as well as the computational expense of simulation. The document proposes using a genetic algorithm guided by decision trees to more efficiently search for critical test cases. Classification trees are built to partition the input space into homogeneous regions in order to better guide the selection and generation of test inputs toward more critical areas.

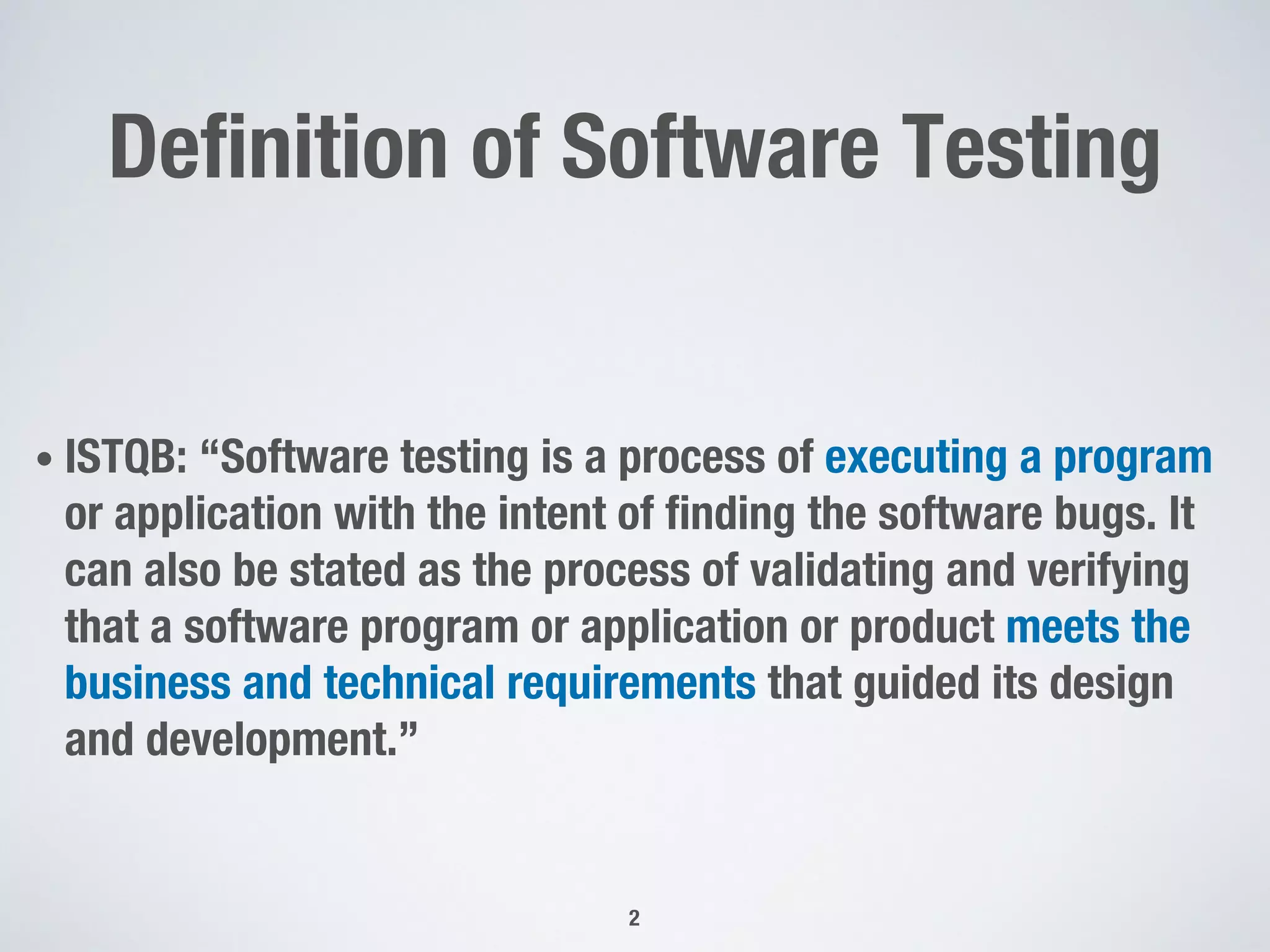

![Software Testing

9

SW Representation

(e.g., specifications)

SW Code

Derive Test cases

Execute Test cases

Compare

Expected

Results or properties

Get Test Results

Test Oracle

[Test Result==Oracle][Test Result!=Oracle]

Automation!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-181208032007/75/Presentation-by-Lionel-Briand-9-2048.jpg)

)

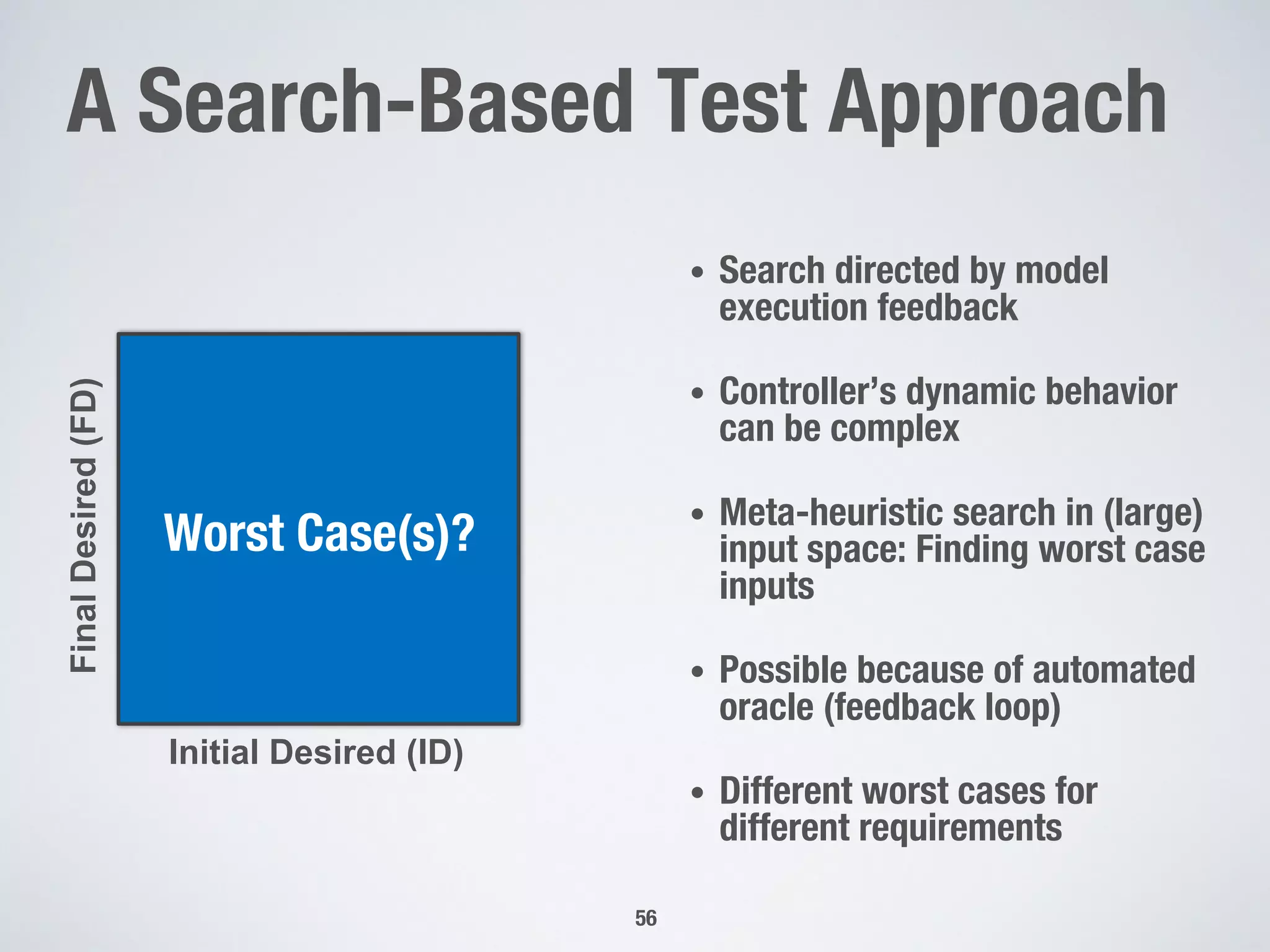

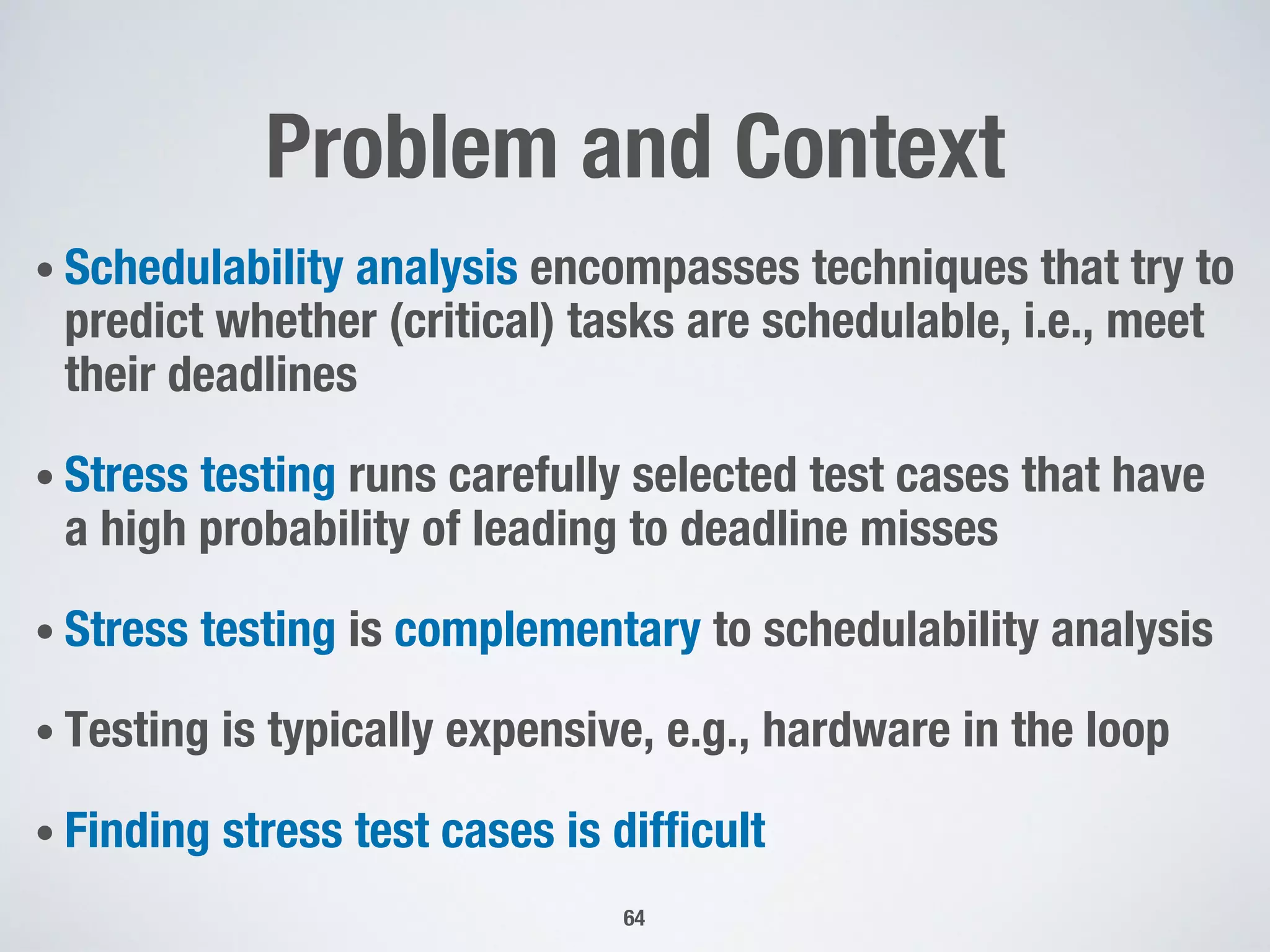

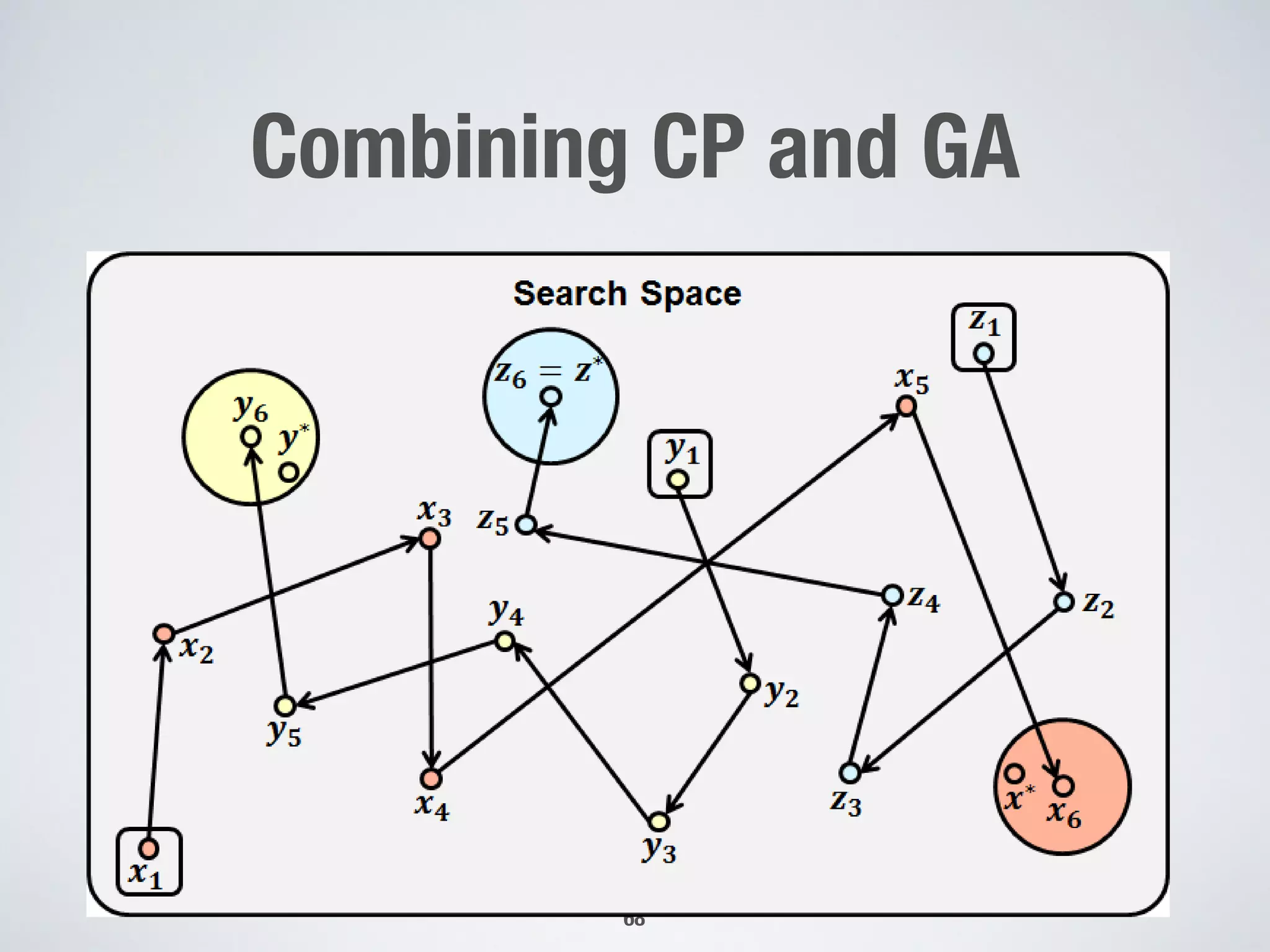

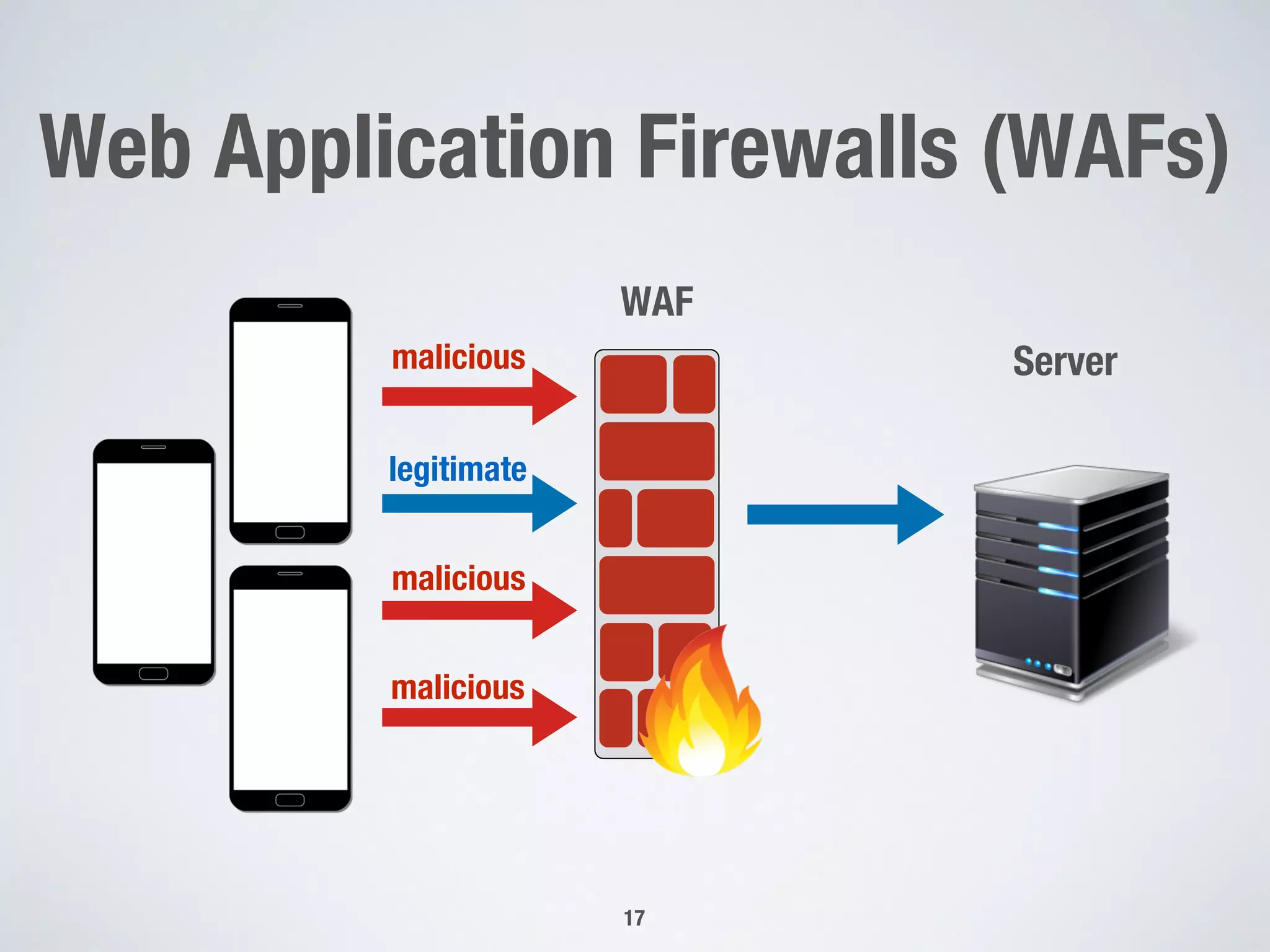

RoadTopology

(CR = [10 40](m))

“non-critical” 31%

“critical” 69%

“non-critical” 72%

“critical” 28%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-181208032007/75/Presentation-by-Lionel-Briand-45-2048.jpg)

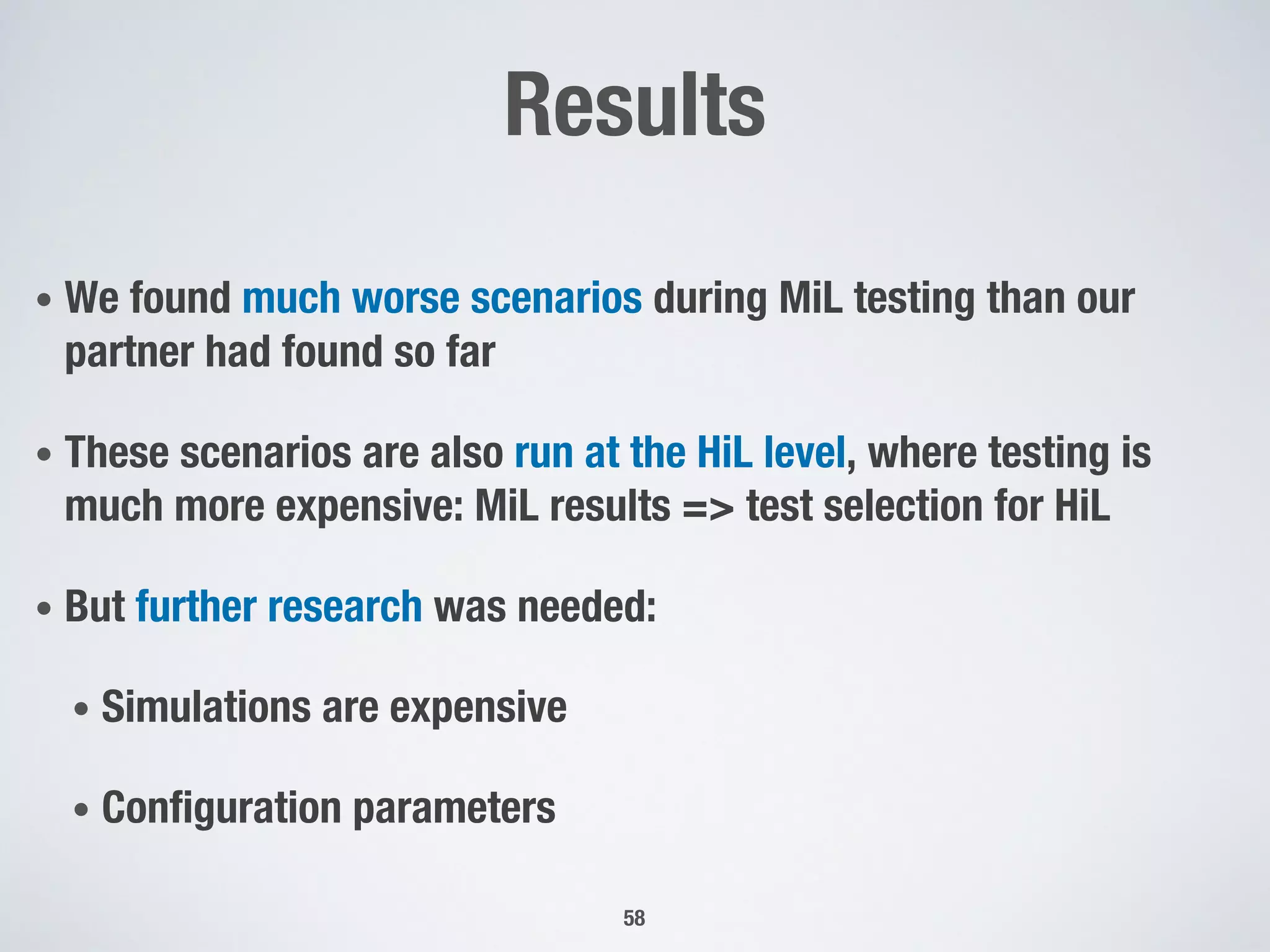

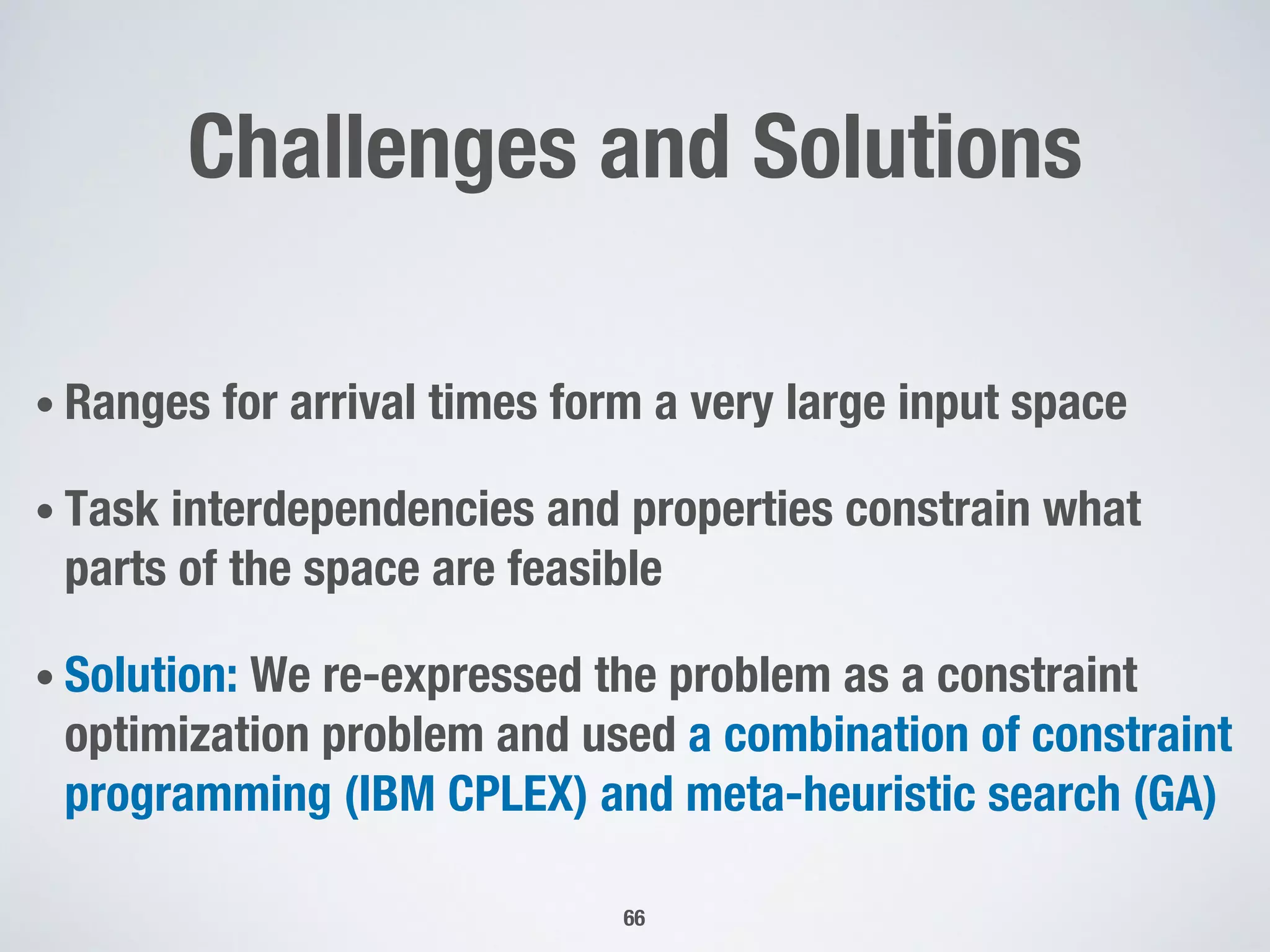

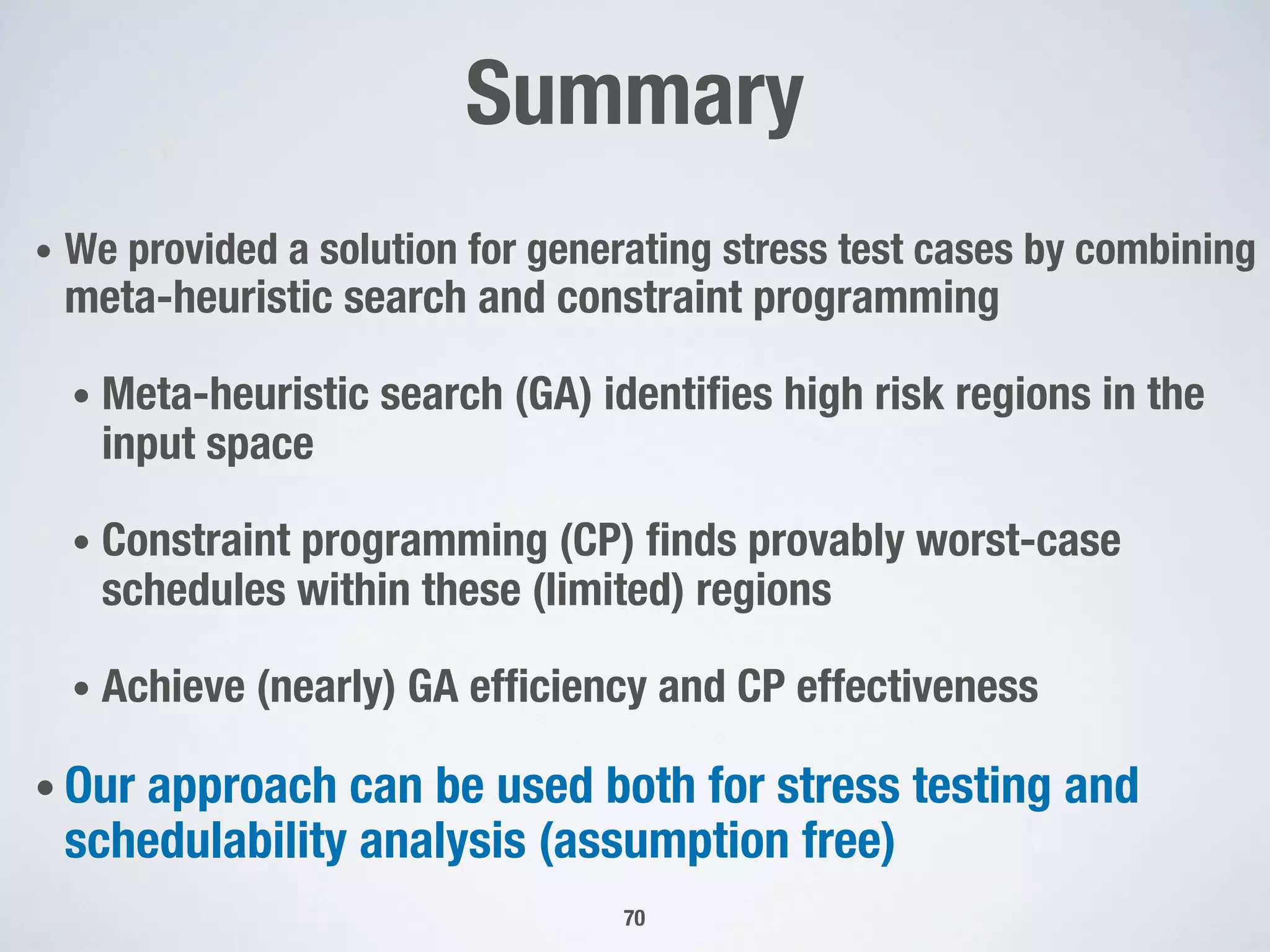

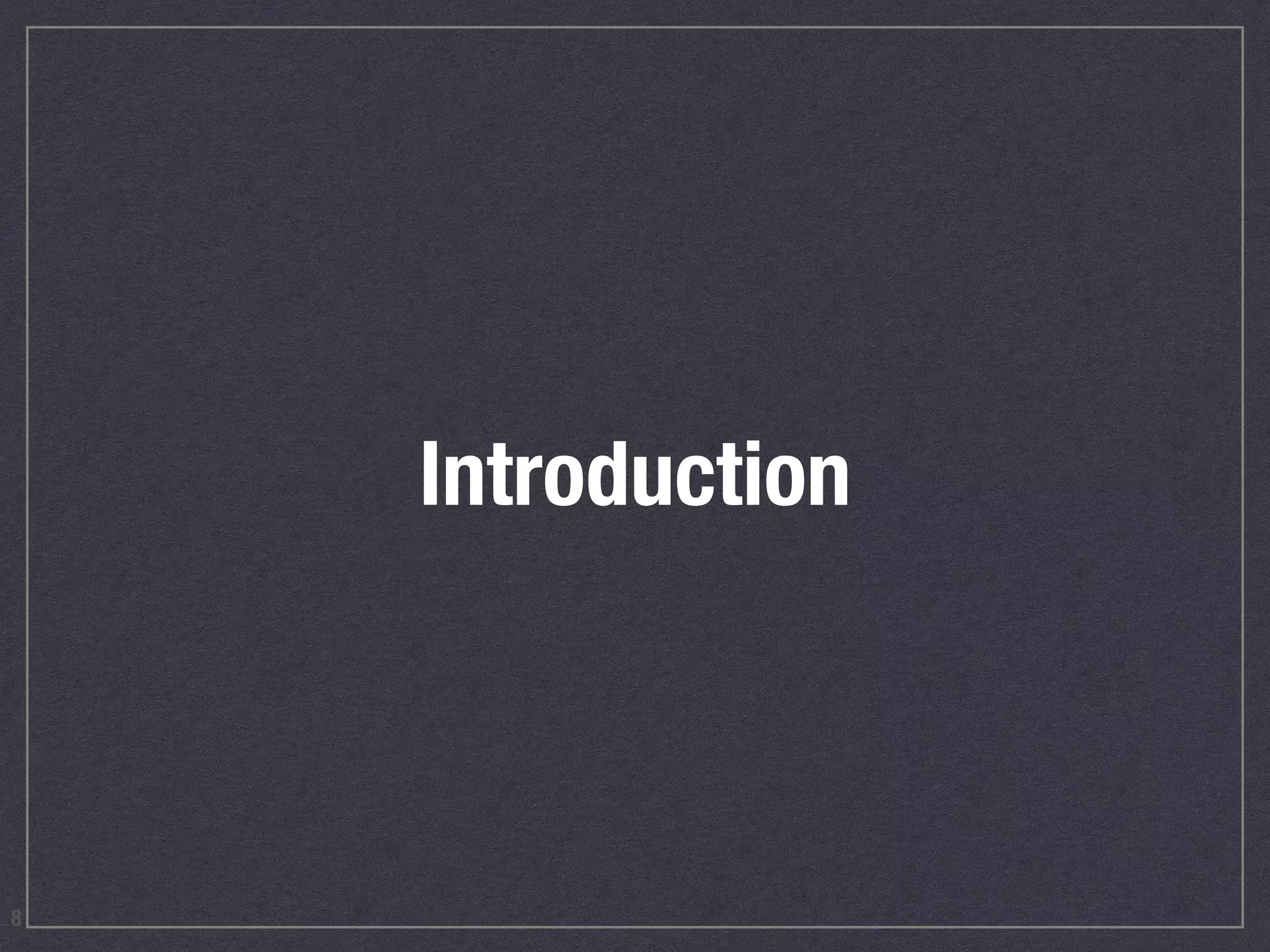

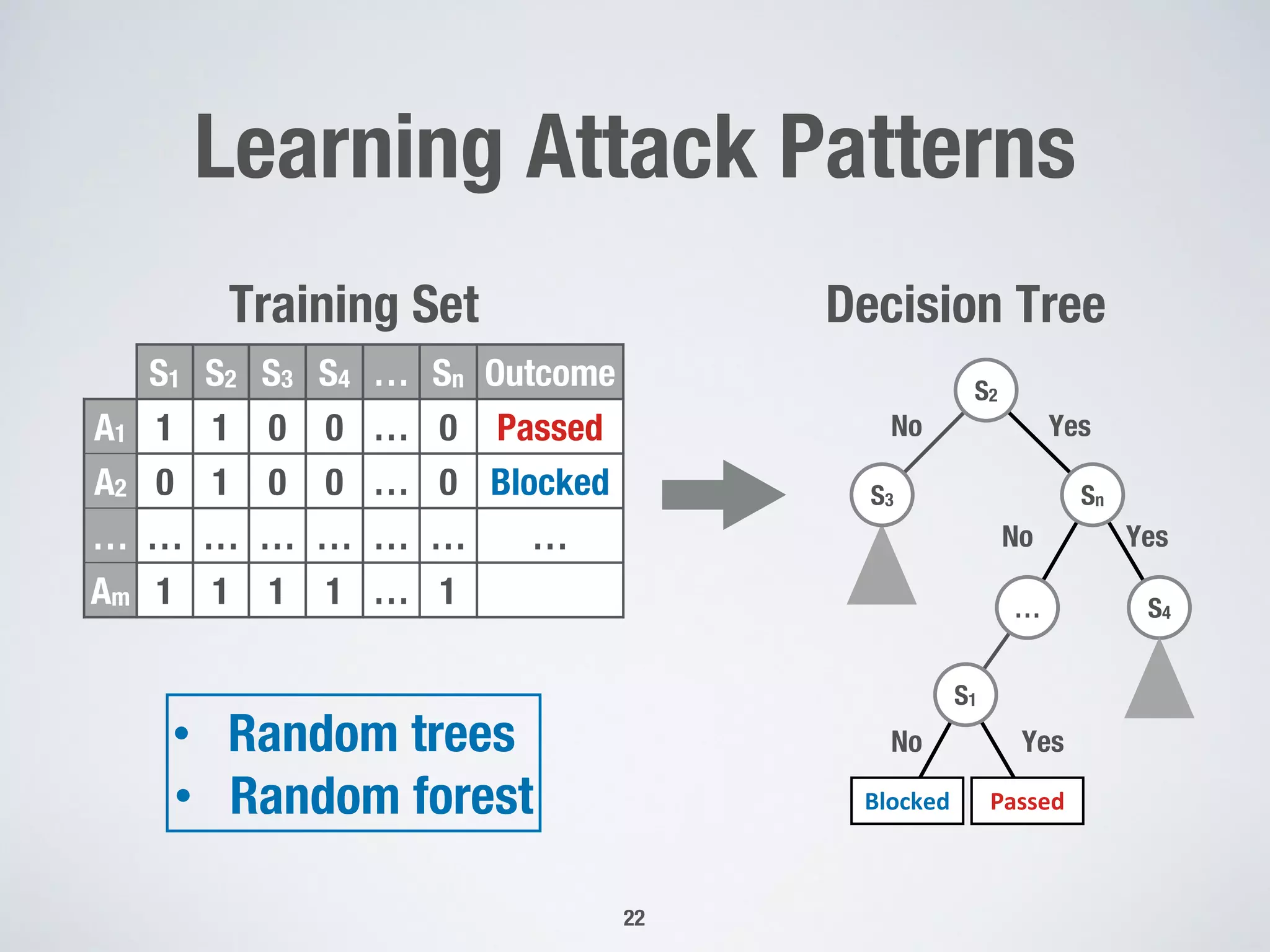

![• Supercharger bypass flap controller

üFlap position is bounded within

[0..1]

üImplemented in MATLAB/Simulink

ü34 (sub-)blocks decomposed into 6

abstraction levels

Supercharger

Bypass Flap

Supercharger

Bypass Flap

Flap position = 0 (open) Flap position = 1 (closed)

Simple Example

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-181208032007/75/Presentation-by-Lionel-Briand-52-2048.jpg)