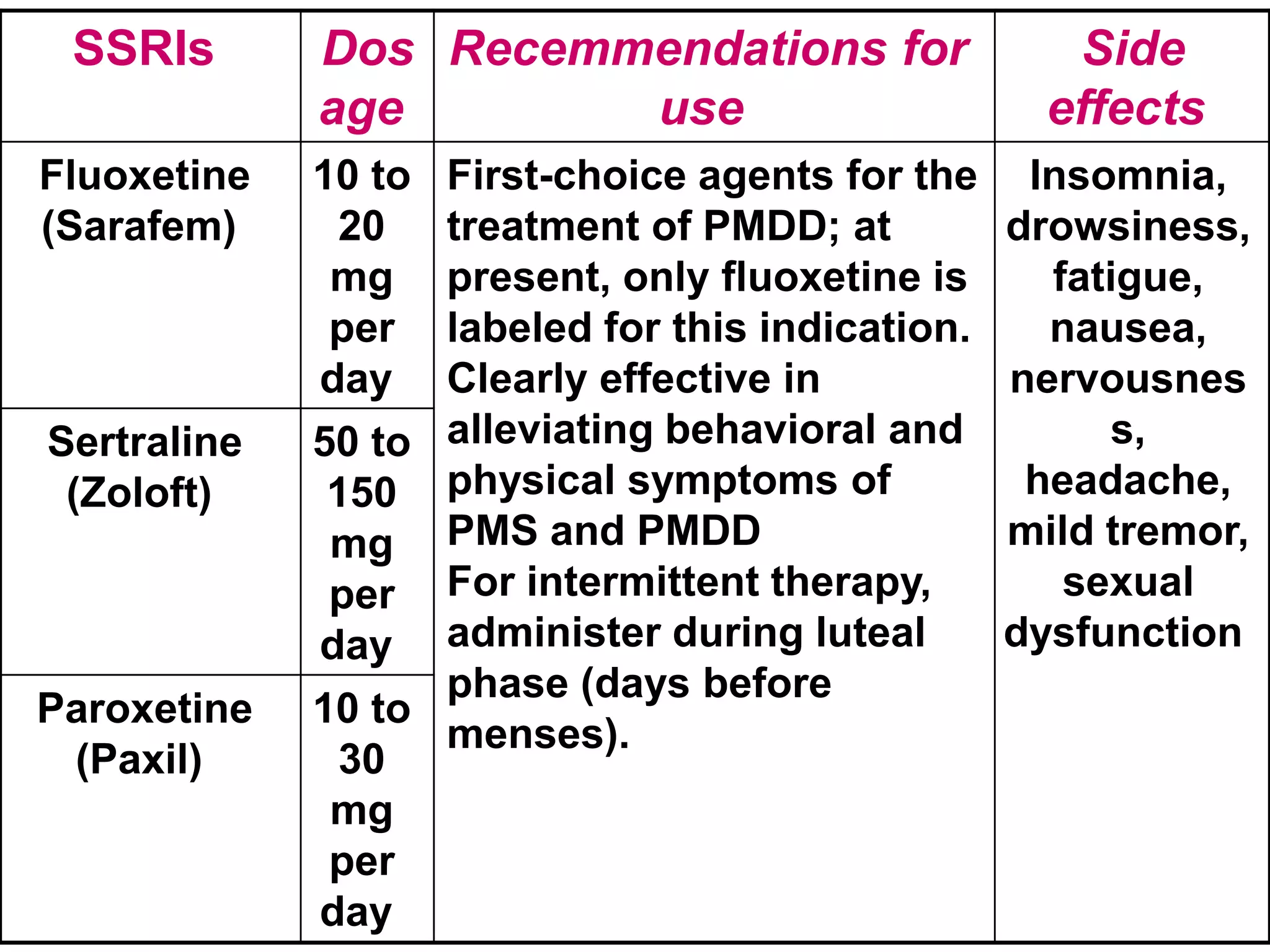

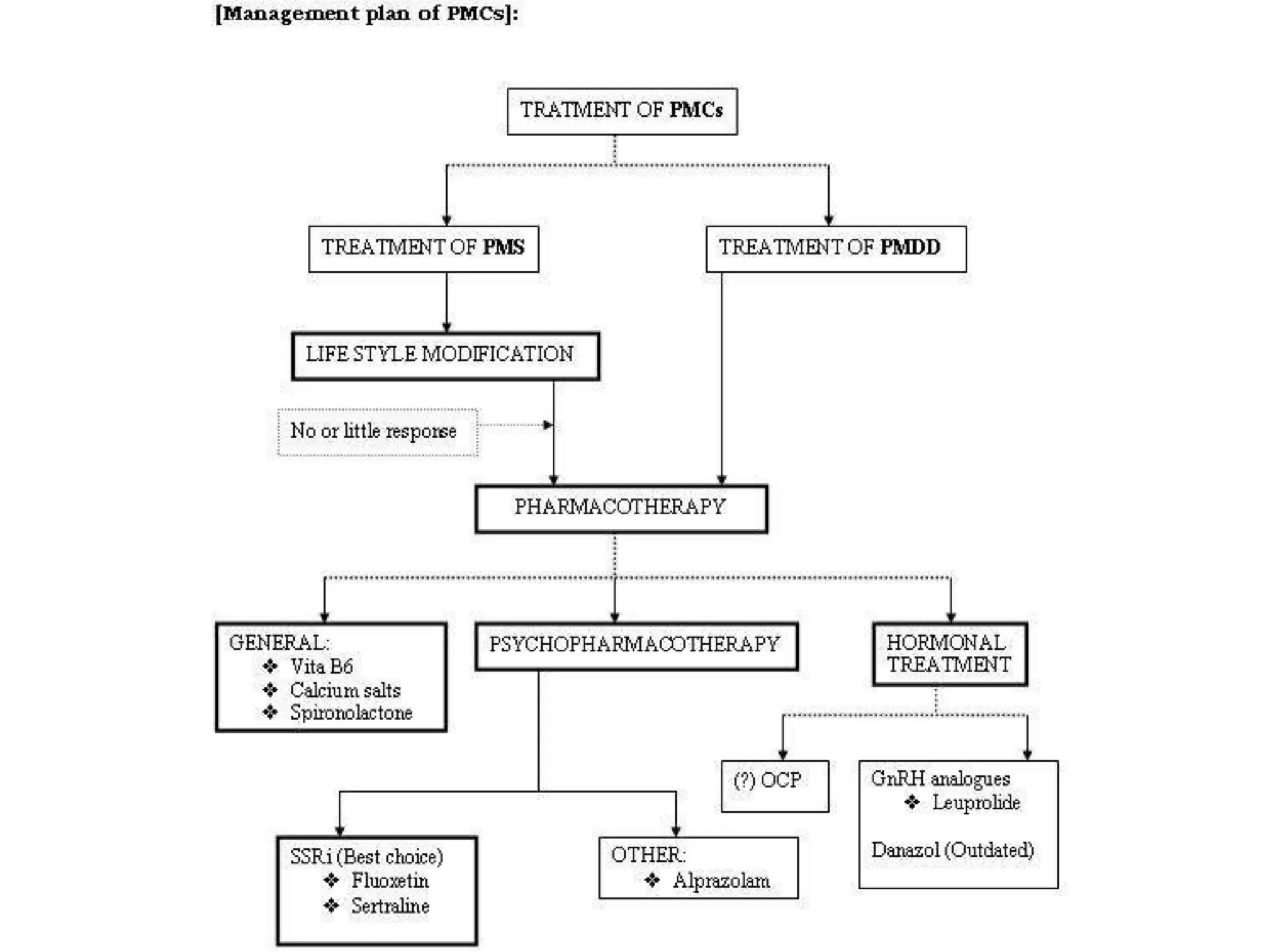

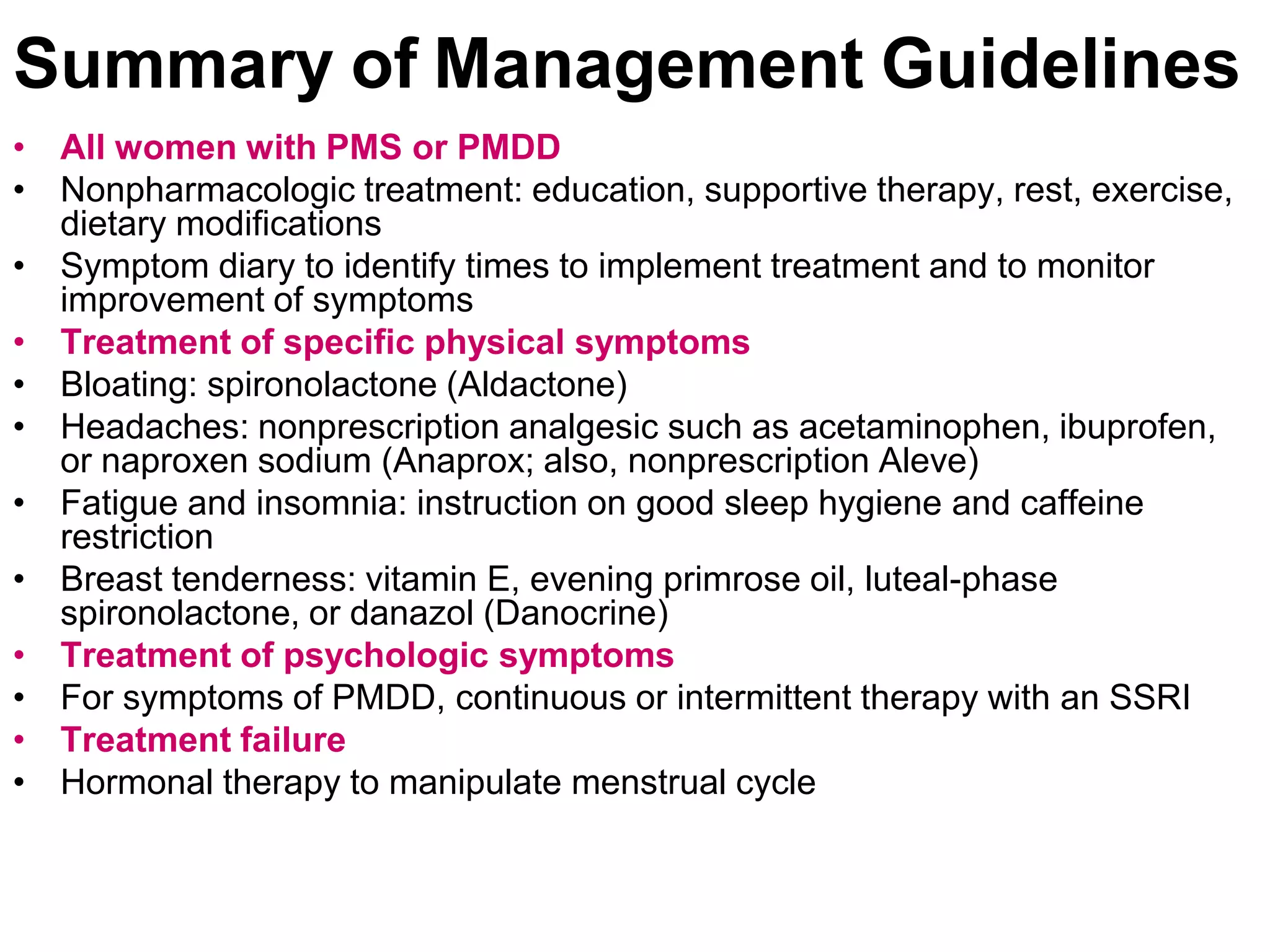

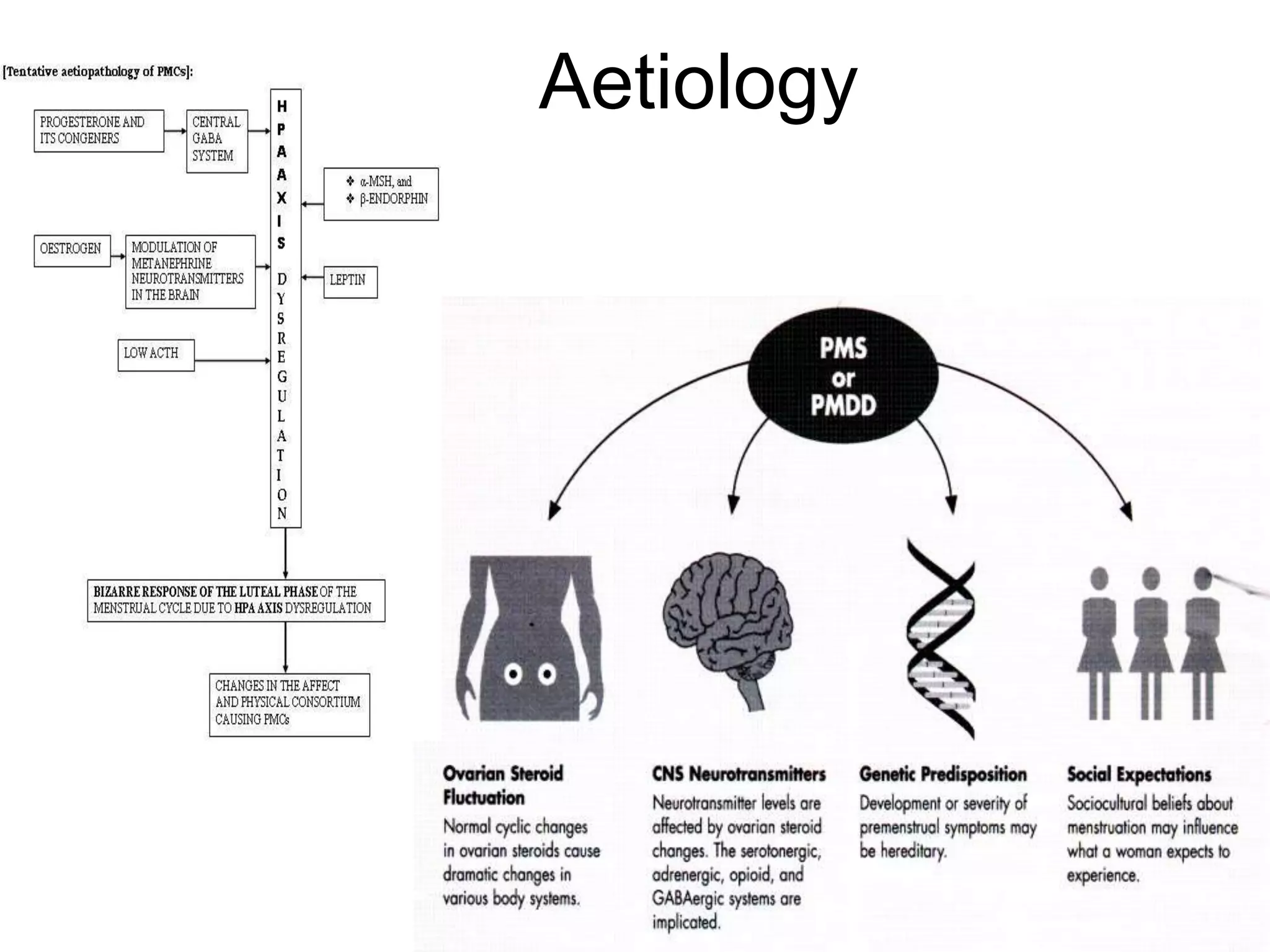

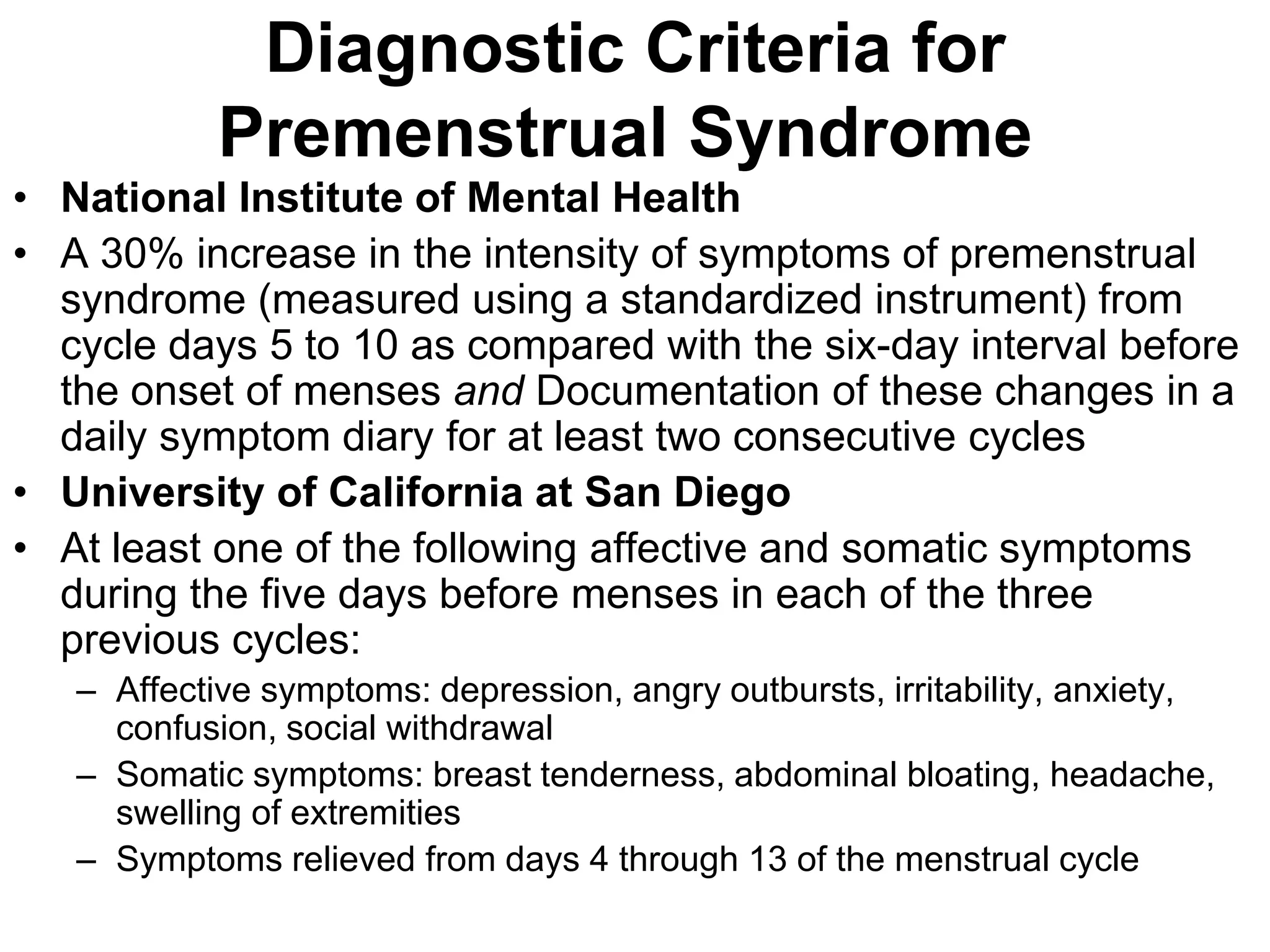

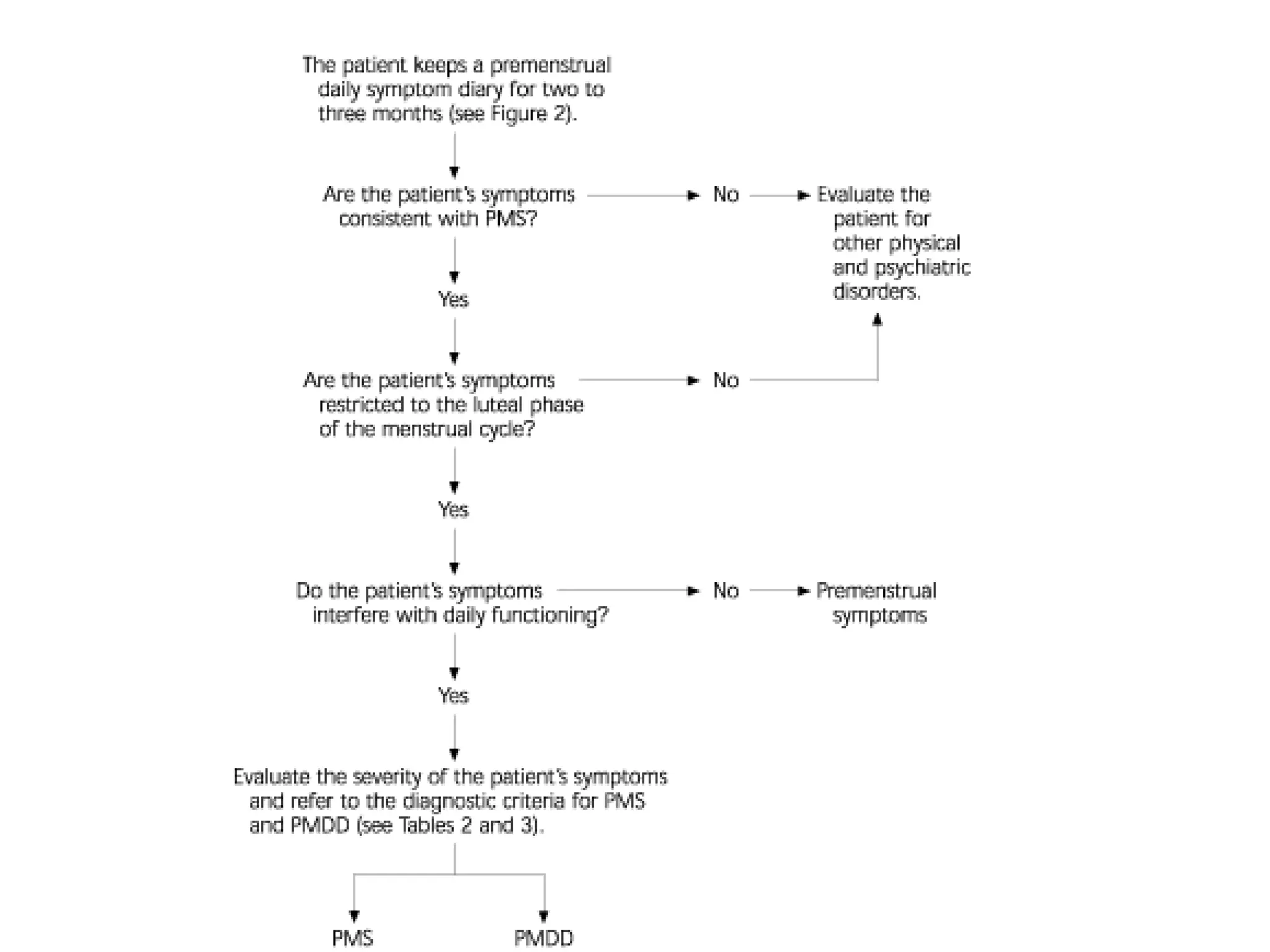

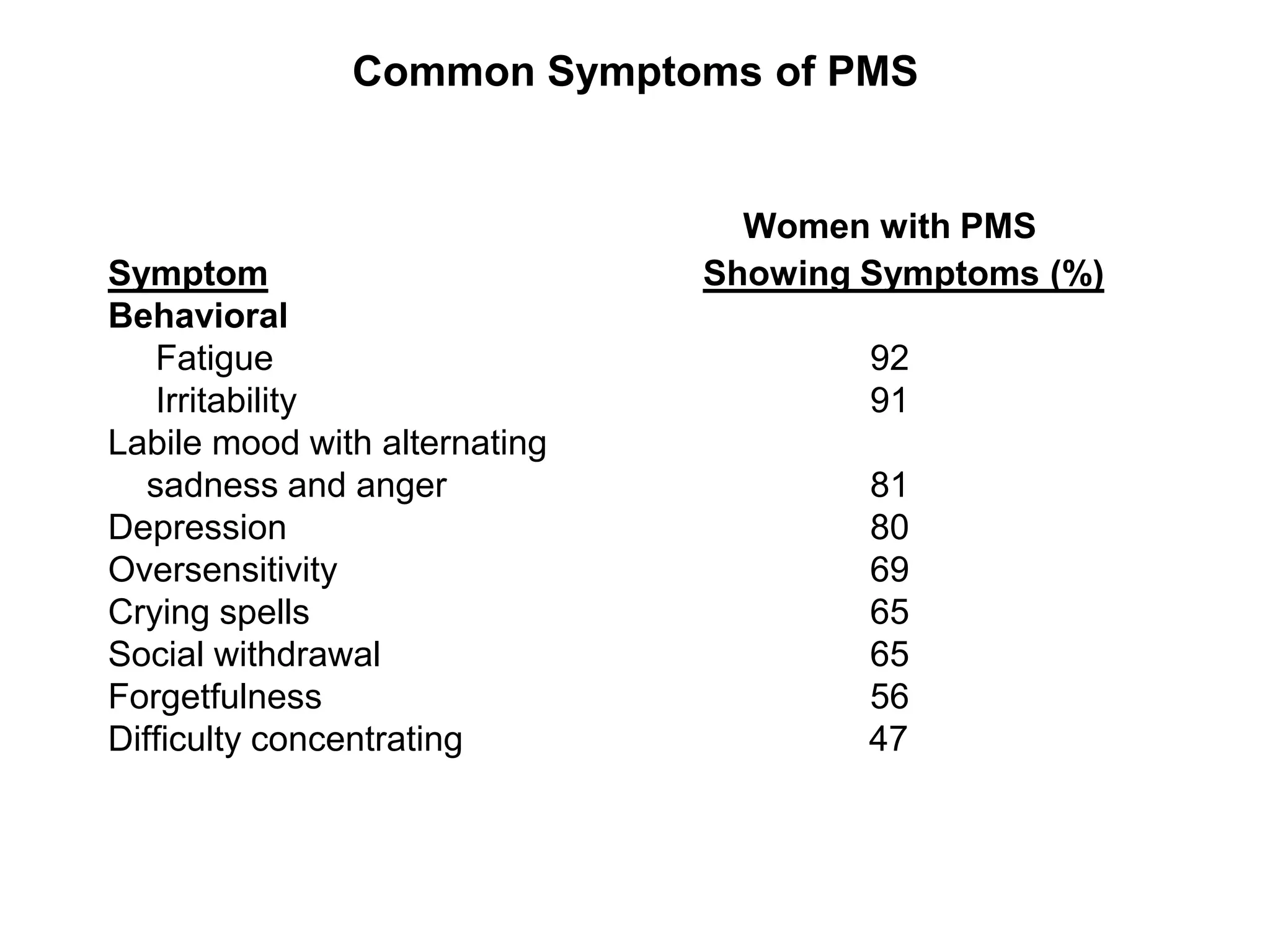

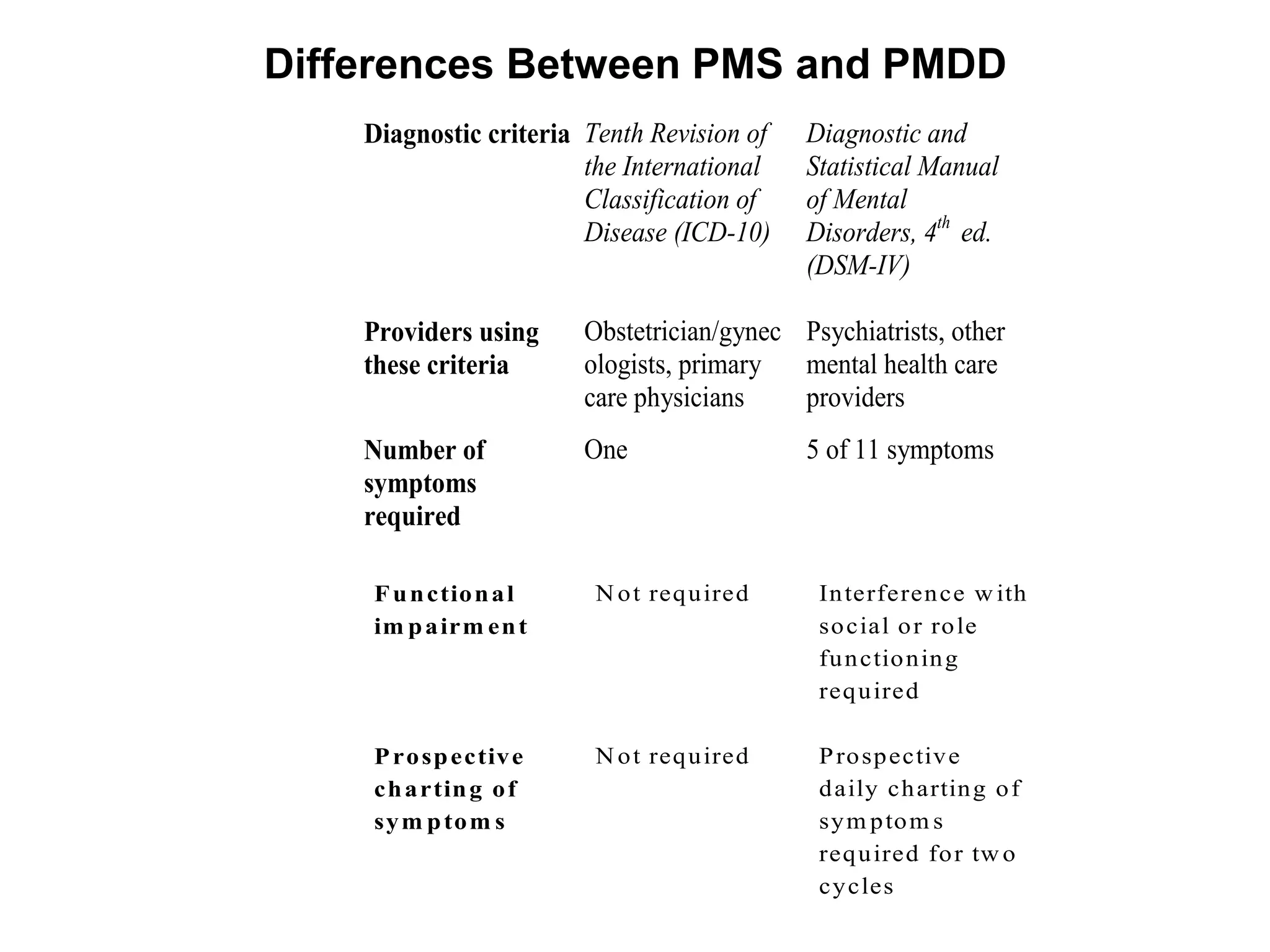

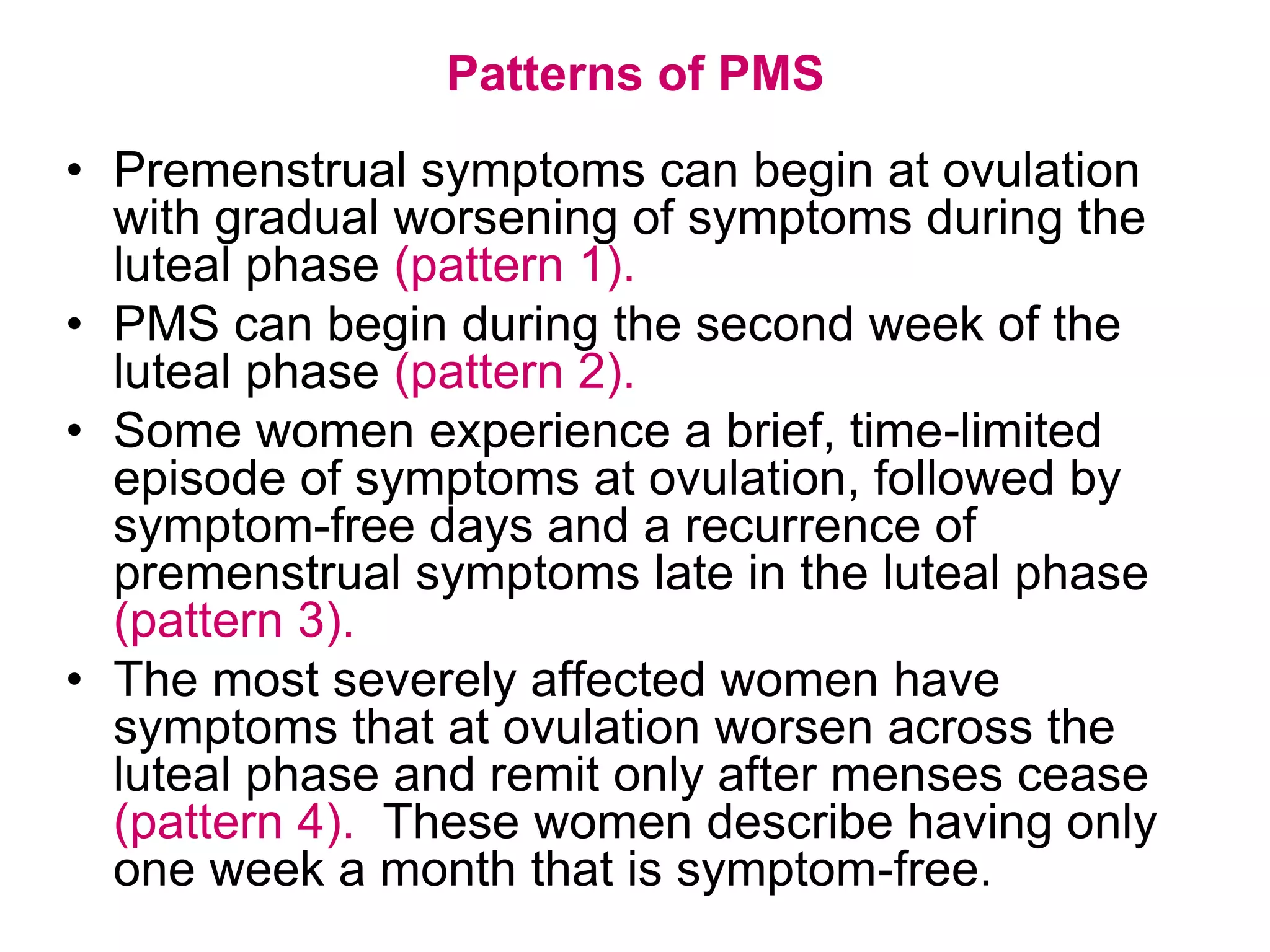

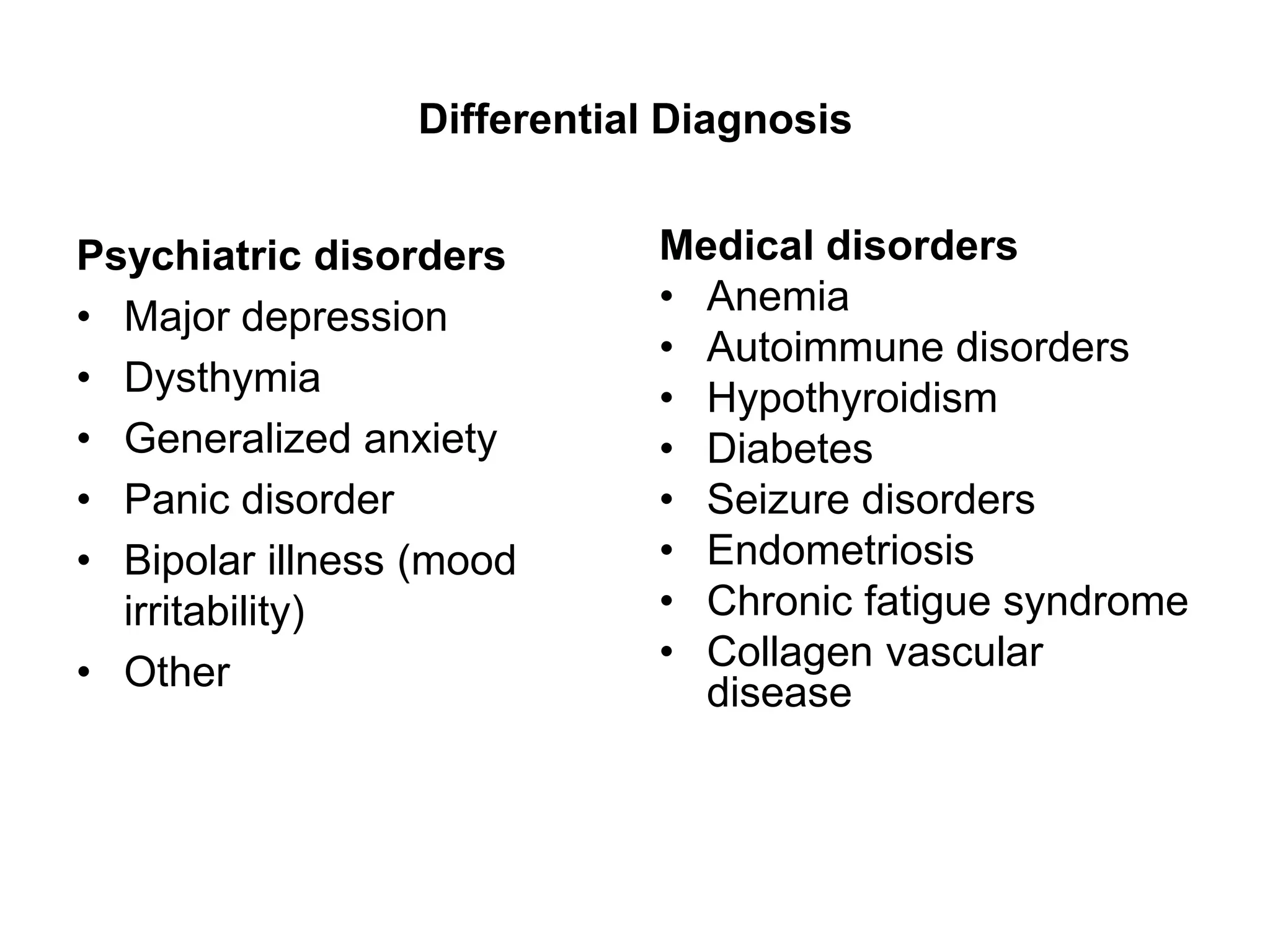

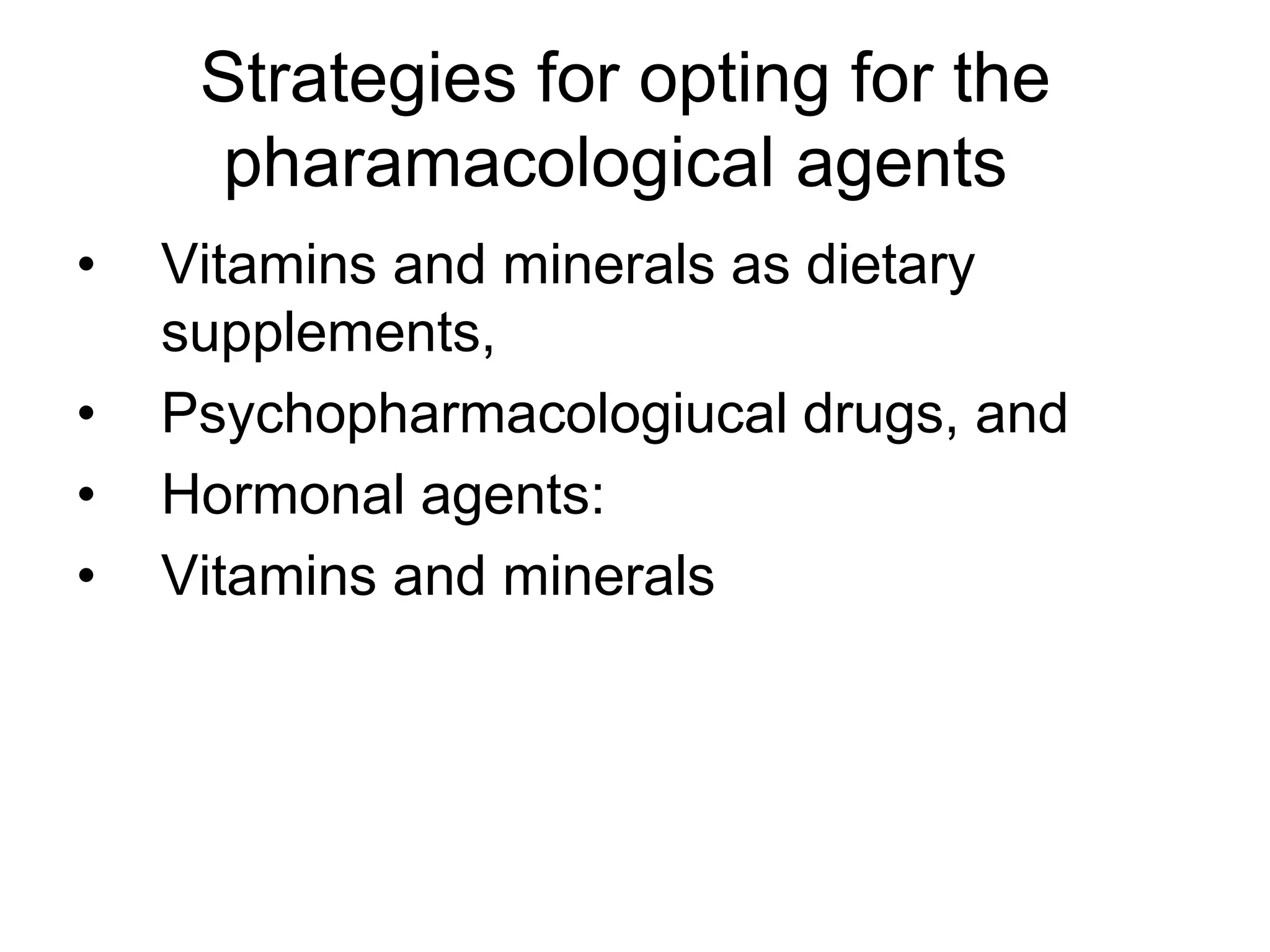

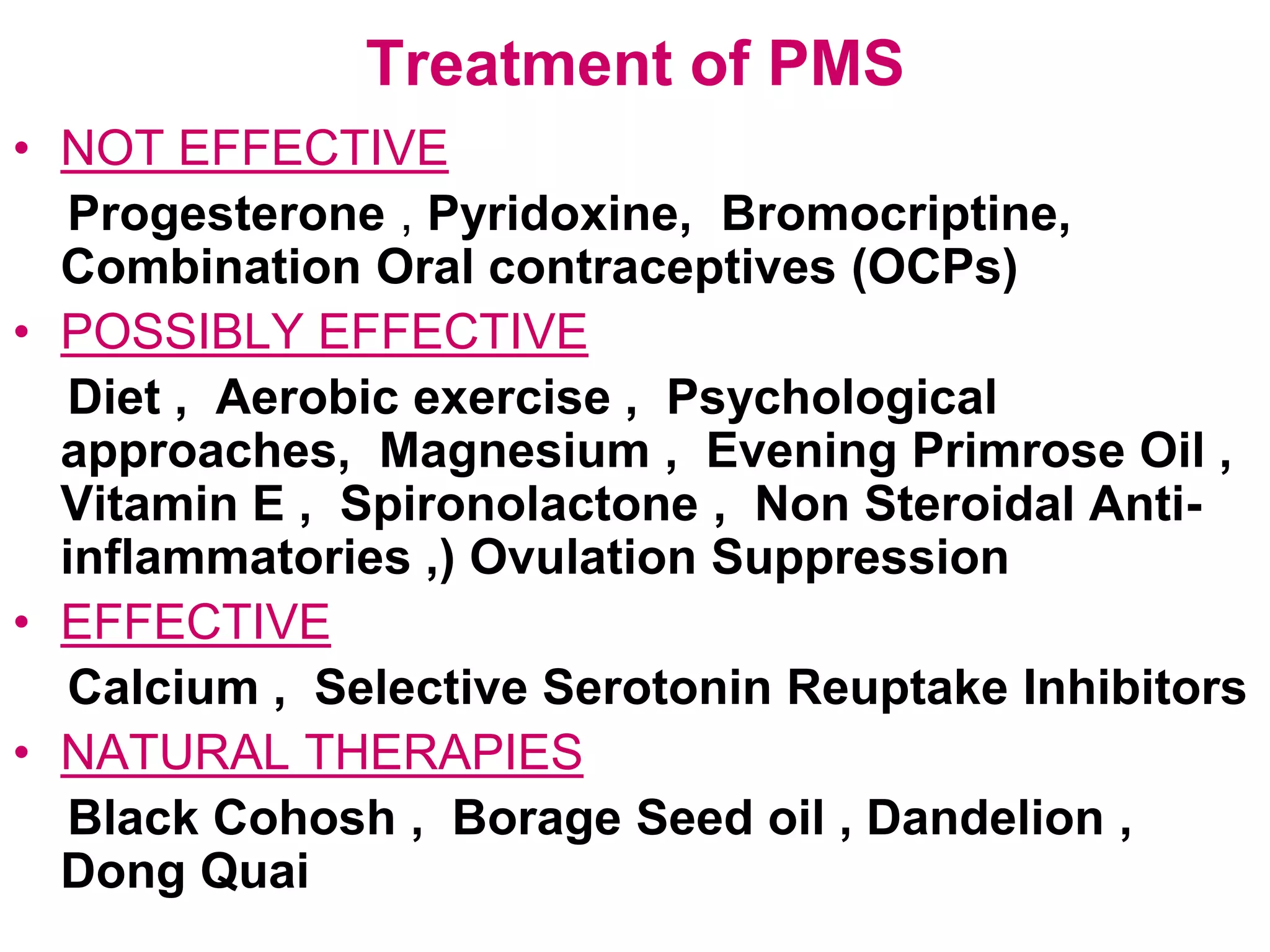

This document discusses premenstrual changes (PMCs), also known as premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMCs involve both psychiatric and gynecological symptoms that occur cyclically in the luteal phase before menstruation. Symptoms can range from mild mood changes to severe mental and physical disturbances. While the exact causes are unclear, serotonin levels are believed to play a role. Treatment involves lifestyle modifications and medications depending on symptom severity, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and calcium supplements showing effectiveness for more severe symptoms.

![• The ACOG recommends SSRIs as initial drug therapy

in women with severe PMS and PMDD. [Evidence

level C, expert/consensus guidelines]

• Common side effects of SSRIs include insomnia,

drowsiness, fatigue, nausea, nervousness, headache,

mild tremor, and sexual dysfunction.

• Use of the lowest effective dosage can minimize side

effects. Morning dosing can minimize insomnia.

• In general, 20 mg of fluoxetine or 50 mg of sertraline

taken in the morning is best tolerated and sufficient to

improve symptoms.

• Benefit has also been demonstrated for the

continuous administration of citalopram (Celexa).

• alleviating physical and behavioral symptoms, with

similar efficacy for continuous and intermittent](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pms2-100418230033-phpapp02/75/Premenstrual-Problems-42-2048.jpg)