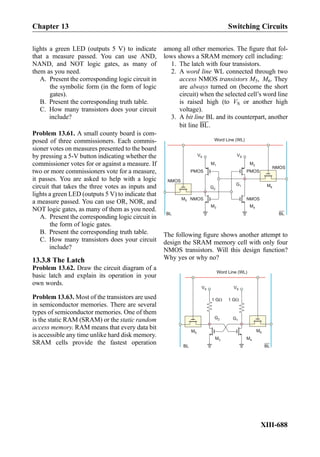

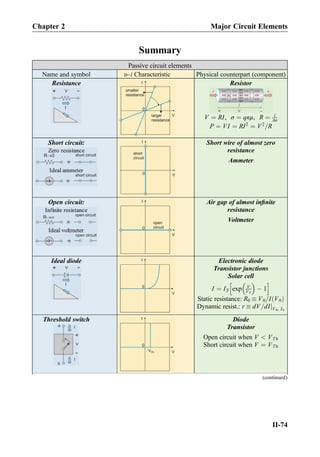

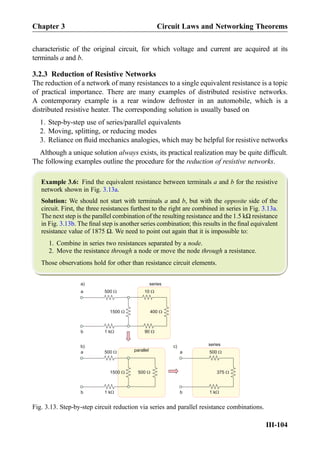

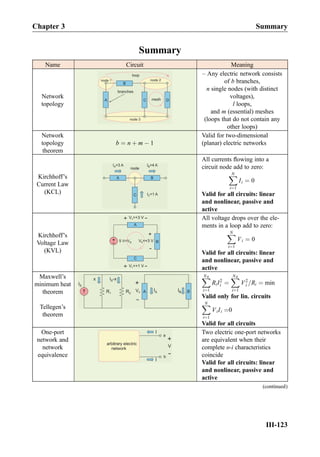

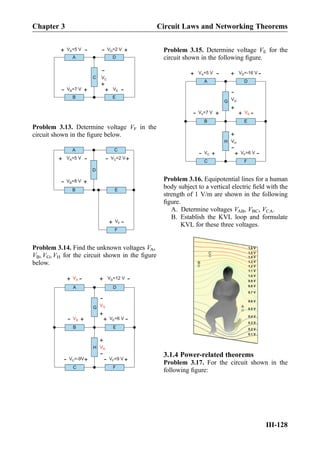

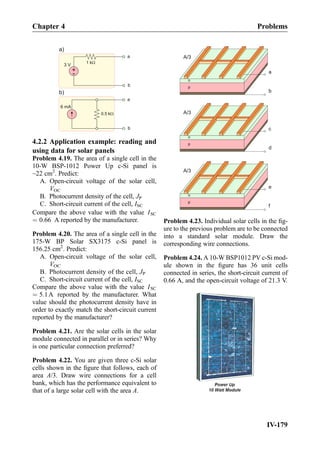

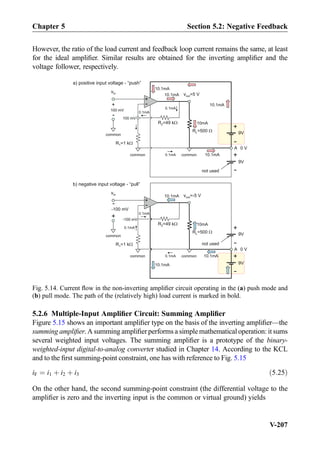

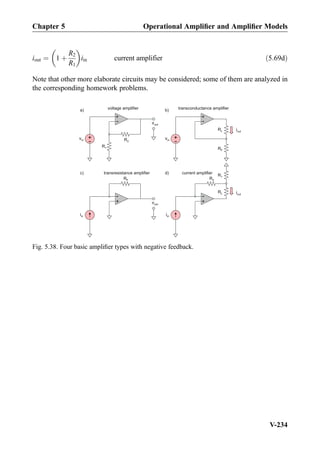

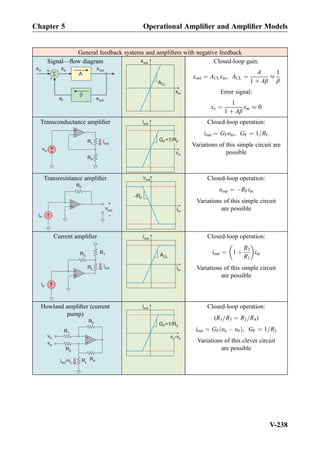

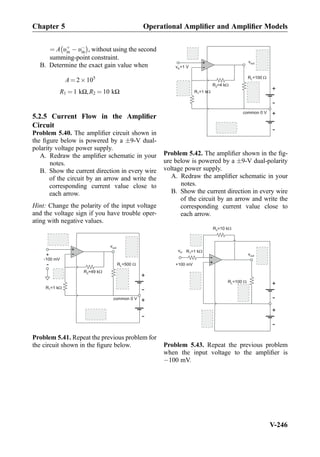

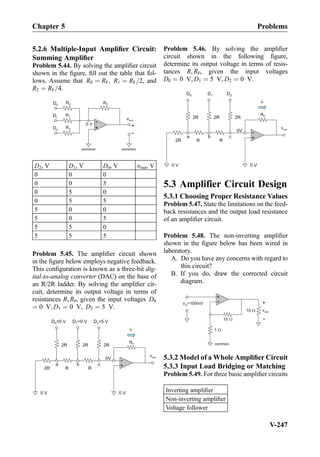

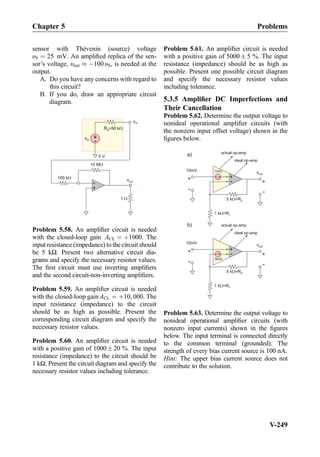

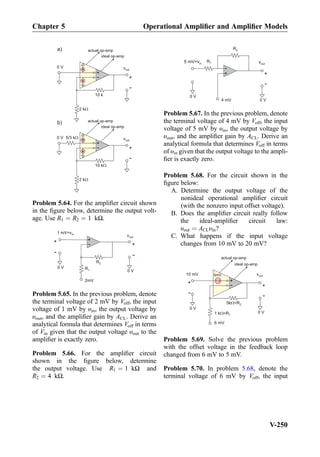

This document provides an overview of the book "Practical Electrical Engineering" by Sergey N. Makarov, Reinhold Ludwig, and Stephen J. Bitar. The book covers topics in electrical engineering including electrostatics, circuit theory, circuit elements, circuit analysis methods, operational amplifiers, and amplifier models. It is intended to provide practical knowledge of electrical engineering concepts for applications. The book contains chapters on major circuit elements, circuit laws and theorems, circuit analysis and power transfer, and operational amplifiers. It also includes examples and analogies to help explain different electrical engineering topics.

![having the opposite current directions, respectively. The lines of the combined magnetic

field are shown in Fig. 1.7b. They are always perpendicular to the lines of force for the

electric field. The magnetic-field magnitude in Fig. 1.7b also has its maximum exactly

between the two conducting wires, at the line connecting its centers.

Exercise 1.10: Determine the magnetic-field magnitude in the middle between two

parallel long wires carrying current of Æ1 A each and separated by 2 cm.

Answer: H ~rð Þ ¼ 31.8 A/m.

Another useful form of Ampere’s law is the magnetic field of an infinite “current

sheet,” i.e., when current flows in a thin conducting sheet in one direction. The sheet may

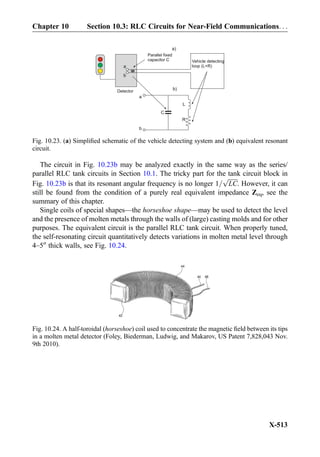

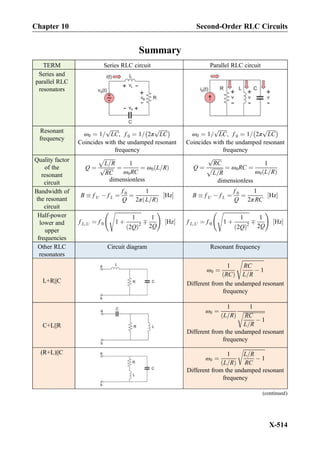

be thought of as an infinite number of parallel thin wires carrying the same current. If

j [A/m] is the current density per unit of sheet width, then the resulting constant field is

H ¼

1

2

j ¼ const ð1:11Þ

1.2.5 Origin of Electric Power Transfer

We know from physics classes that electric power P delivered to the load is given by the

product P ¼ VI where V is the voltage across the load and I is the current through it. How

exactly is this power transferred to the load? To answer this question, we assume a

transmission line in the form of two parallel sheets of width W and spacing l shown in

Fig. 1.8. Each sheet carries current density with the magnitude j per unit of sheet length.

When the material conductivity is infinite, the voltage between the two sheets is the

load voltage V. For l=W 1, Eq. (1.9) yields the electric field within the transmission

line,E ¼ V=l. The magnetic field is found using Eq. (1.11). The result isH ¼ jsince both

sheets contribute to the field within the line. Next, we define a vector

magnetic field (H)

electric field (E)

V

+

-

Poynting vector (S)

to load

W j

Fig. 1.8. Transmission line in the form of two current sheets.

Chapter 1 From Physics to Electric Circuits

I-16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-38-320.jpg)

![transformer shown in Fig. 1.10d operates with alternating currents. One mechanical

analogy is a gear transmission or gearbox. In terms of angular speed ω [rad/s] and

developed torque T N Á m½ Š, one has T2 ¼ D2=D1ð ÞT1, and ω2 ¼ D1=D2ð Þω1, where

D1,2 are pitch diameters of gear wheels. Here, torque is the voltage and speed is the

current. D1,2 are similar to the number of turns, N1,2, of the primary and secondary coils of

the transformer, respectively. This analogy ignores the field effect—magnetic coupling

between the coils. Therefore, it will fail in the DC case. A more realistic transformer

analogy is shown in Fig. 1.10e. The model with four pistons transforms power from one

circuit to another in the AC case only. It is drawn for a 1:1 transformer. When a

transformer with a turn ratio of 2:1 is required, the area of output pistons is doubled.

This doubles the output current, but the output voltage (the force) will be halved.

1.3.3 Analogies for Semiconductor Circuit Components

Semiconductor circuit components are similar to fluid valves, which are either externally

controlled or are controlled by the fluid-flow pressure itself. Figure 1.11a shows a hydraulic

analogy for a diode. This picture highlights its major function: a one-way valve. Fig. 1.11b

illustrates the operation of an n-channel metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor,

or NMOS transistor. This transistor is a valve controlled by a third voltage terminal. For

another bipolar junction transistor or BJT in Fig. 1.11c, not only the control voltage but

also the control current is important. In other words, to keep the valve open, we must also

supply a small amount of current (fluid) at the control terminal.

NMOS transistor

a)

semiconductor diode

b)

+ -

higher pressure lower pressure

flexible membrane

control pressure

control voltage

junction transistor

c) control pressure/current

control voltage/current

Fig. 1.11. Analogies for semiconductor circuit components.

Chapter 1 From Physics to Electric Circuits

I-20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-42-320.jpg)

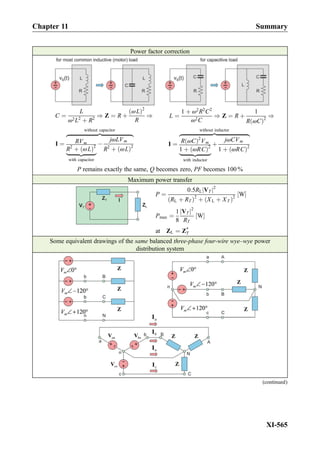

![Summary

Electrostatics

Electric voltage/electric potential VAA

0 ¼ 1 V )Work of 1 J is necessary to bring the 1 C of

charge from point A0

to point A against the field;

VAA

0 ¼ À

ðA

A

0

~E Á d~l for any contour 1, 2, or 3;

~E ~rð Þ ¼ ÀgradV ~rð Þ ¼ À∇V ~rð Þ for potential V ~rð Þ

everywhere in space including materials;

V ¼ lE in uniform fields (most important).

Coulomb force on charge q ~F ¼ q~E [N]

The force is directed along the field for positive charges and

against the field for negative charges

Gauss law Total flux of the electric field through closed surface S times

the permittivity is the total charge enclosed by S.

Q

ε0

¼

ð

S

~E Á ~n dS (ε0 =8.854Â10À12

F/m)

Equipotential conductors Within conductor(s) with applied voltage:

– Electric field is exactly zero;

– Volumetric charge density (C/m3

) is exactly zero.

On surface(s) of conductor(s) with applied voltage:

– Every point has the same voltage (conductor surface is

equipotential surface);

– Surface charge density (C/m2

) exists;

– Emanating electric field is perpendicular to the surface

(tangential field is zero: ~Et ¼ 0)

Outside conductor(s):

– Equipotential lines and lines of force are perpendicular

to each other

Voltage between two wires – Metal wires “guide” the electric field/voltage to a remote

point

– Given the same voltage, charges on wires increase when

their length increases.

Electrical induction in electrostatics – Conductors 1 and 2 are subject to applied voltages V1, V2;

– Conductor 3 has zero net charge;

– Conductor 3 acquires certain voltage V3;

– Surface charges in conductor 3 are separated as shown in

the figure.

(continued)

Chapter 1 Summary

I-21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-43-320.jpg)

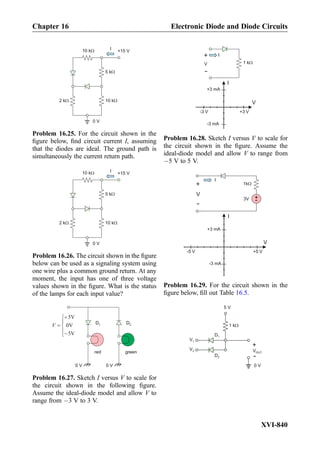

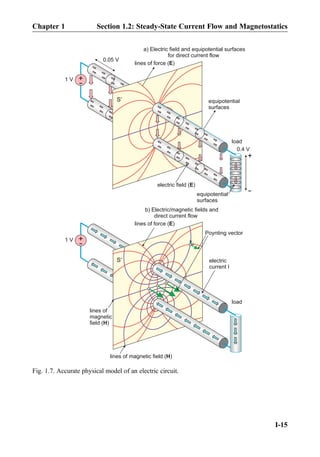

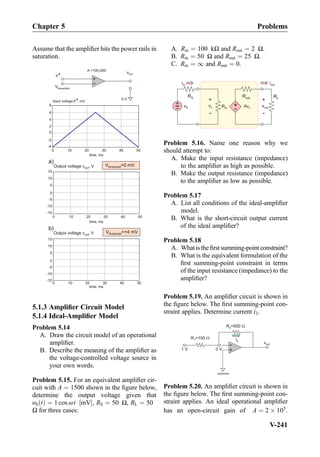

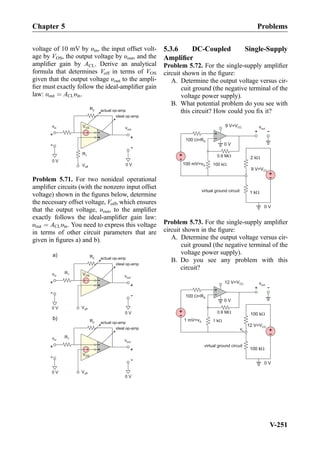

![Problems

1.1 Electrostatics of

Conductors

1.1.2 Electric Potential and Electric

Voltage

1.1.3 Electric Voltage Versus Ground

1.1.4 Equipotential Conductors

Problem 1.1. Determine voltage (or potential)

VAB and VBA (show units) given that the electric

field between points A and B is uniform and has

the value of 5 V/m. Point A has coordinates

(0, 0); point B has coordinates (1, 1).

E

A

B

Problem 1.2. Determine voltages VAB, VBD,

and VBC given that the electric field shown in

the figure that follows is uniform and has the

value of (A) 10 V/m, (B) 50 V/m, and

(C) 500 V/m.

0 cm

E

5 cm

10 cm

A

B

C

D

Problem 1.3. Assume that the electric field

along a line of force AA0

has the value 1Âl V/

m where 0 l 1 m is the distance along the

line. Find voltage (or potential) VAA

0 .

Problem 1.4. The electric potential versus

ground is given in Cartesian coordinates by V

~rð Þ ¼ Àx þ y À z [V]. Determine the

corresponding electric field everywhere in space.

Problem 1.5. The figure below shows the

electric potential distribution across the semi-

conductor pn-junction of a Si diode. What

kinetic energy should the positive charge

(a hole) have in order to climb the potential

hill from anode to cathode given that the hill

“height” (or the built-in voltage of the

pn-junction) is Vbi ¼ 0:7 V? The hole charge

is the opposite of the electron charge. Express

your result in joules.

Vbi

anode cathode

Problem 1.6. Is the electric field shown in the

figure that follows conservative? Justify your

answer.

0

E

1 cm

2 cm

A

B

C

D

Problem 1.7. List all conditions for voltage and

electric field used in electrostatic problems.

Problem 1.8. The figure below shows a 345 kV

power tower used in MA, USA—front view. It

also depicts electric potential/voltage and elec-

tric field distributions in space:

A. Determine which figure corresponds to

the electric potential and which to the

magnitude of the electric field.

B. Provide a detailed justification of your

answer.

Chapter 1 Problems

I-23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-45-320.jpg)

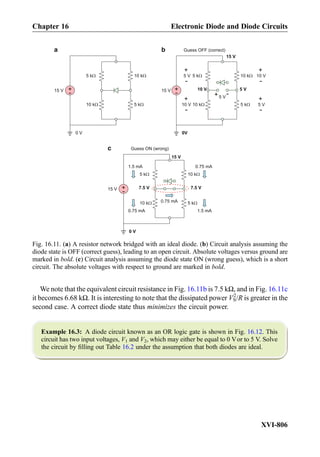

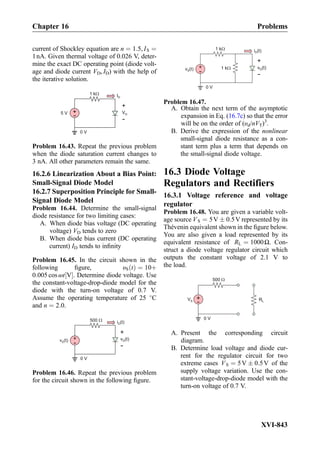

![follows Ohm’s law. It is therefore the nonlinear circuit element. The third element in

Fig. 2.12 corresponds to an ideal (Shockley) diode. The diode does not conduct at negative

applied voltages. At positive voltages, its υ-i characteristic is very sharp (exponential).

The diode is also the nonlinear circuit element. Strictly speaking, the υ-i characteristic of the

incandescent light bulb does not belong to the list of circuit elements due to its limited

applicability. However, the ideal diode is an important nonlinear circuit element. The

nonlinear elements are generally polar (non-symmetric) as Fig. 2.12c shows.

2.2.3 Static Resistance of a Nonlinear Element

Once the υ-i characteristic is known, we can find the static resistance R(V) of the nonlinear

circuit element at any given voltage V0. For example, the υ-i characteristic of the ideal

diode shown in Fig. 2.12c is described by the exponential Shockley equation:

I ¼ IS exp

V

VT

À 1

!

ð2:20Þ

In Eq. (2.20), the constant IS [A] is the diode saturation current. The saturation current is

very small. The constant VT [V] is called the thermal voltage.

Example 2.5: Give a general expression for the diode resistance R(V) using Eq. (2.20)

and find its terminal values atV ! 0andV ! 1, respectively. Then, calculate static diode

resistance R0 and diode current I0 when the voltage across the diode is V0 ¼ 0.55 V.

Assume that IS ¼ 1 Â 10À12

A and VT ¼ 25:7 mV.

Solution: Using Eq. (2.20) we obtain

R Vð Þ ¼

V

IS exp

V

VT

À 1

!

ð2:21Þ

WhenV ! 0, we can use a Taylor series expansion for the exponent. Keeping only the first

nontrivial term, one has exp V=VTð Þ % 1 þ V=VT. Therefore,

R Vð Þ !

VT

IS

when V ! 0 or V=VT 1ð Þ ð2:22Þ

This value is very large, in excess of 1 GΩ. The diode is thus the open circuit with a good

degree of accuracy.

On the other hand, at large V, the exponential factor in Eq. (2.21) greatly increases.

Therefore,

R Vð Þ ! 0 when V ! 1 ð2:23Þ

Chapter 2 Major Circuit Elements

II-48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-68-320.jpg)

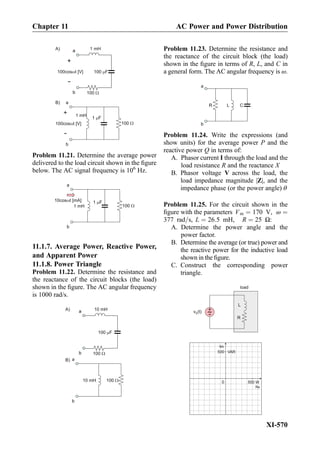

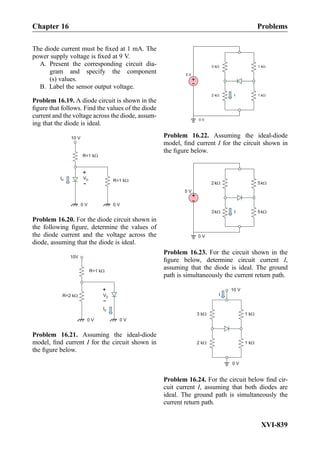

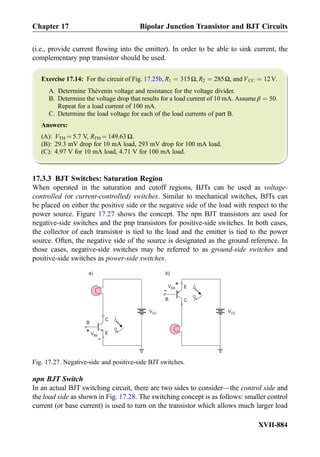

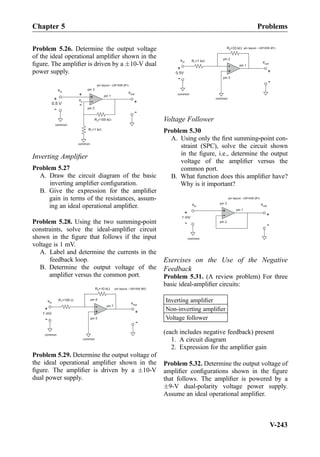

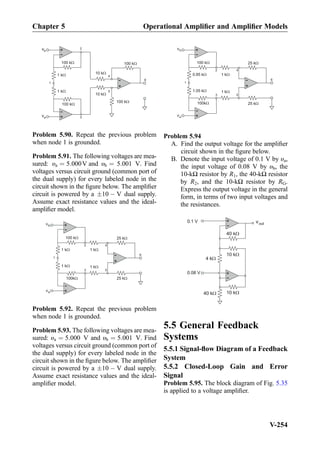

![Active circuit elements

Name and symbol υ–i Characteristic Physical counterpart (component)

Independent voltage

source

Practical voltage source

Independent current

source

Practical current source

Voltage-controlled

voltage source

Transistor

Amplifier

υout ¼ Aυin

A—open-circuit voltage gain

[V/V, V/mV] (dimensionless)

Current-controlled

voltage source

Transistor

Amplifier

υout ¼ Riin

R—transresistance [V/A, V/mA]

(units of resistance, Ω)

Voltage-controlled

current source

Transistor

Amplifier

iout ¼ Gυin

G—transconductance [A/V]

(units of conductance, ΩÀ1

)

Current-controlled

current source

Transistor

Amplifier

iout ¼ Aiin

A—short-circuit current gain

[A/A, A/mA] (dimensionless)

Chapter 2 Summary

II-75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-95-320.jpg)

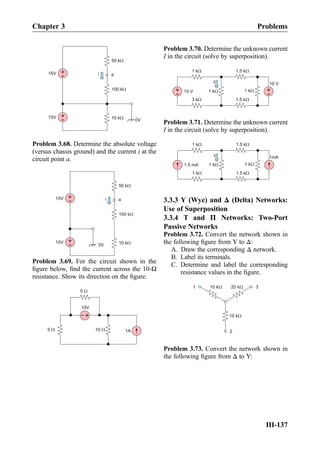

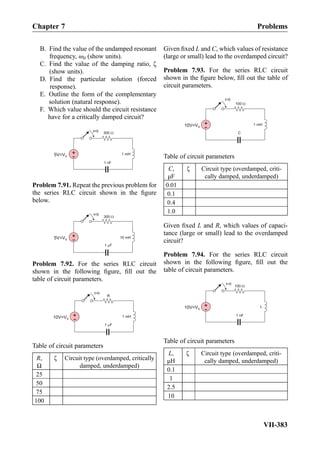

![scale as a function of the value of the unknown

resistance in the range from 10 Ω to 1000 Ω.

Problem 3.48. A voltage divider circuit with R1

¼ 700 Ω (the fixed resistance) and R2 ¼ 700 Ω

Æ 0:1% (the strain gauge) is used. The voltage

power supply is rated at 4.5 V:

A. Show that voltage across the strain

gauge varies in the range 2.25 V Æ

1.125 mV.

B. Could you derive an analytical formula

that gives the voltage variation across R2

¼ R1 Æ Δ as a linear function of an

arbitrary (but very small) resistance var-

iation Δ?

[Hint: use your calculus background—the

Maclaurin series versus a small parameter].

3.2.7 Current Limiter

Problem 3.49. A thermistor is connected to an

ideal voltage power source of 9 V. Determine

the value of the current-limiting resistor

R based on the requirement that the power

delivered to the thermistor should be always

less than 0.1 W. The lowest possible value of

R should be chosen. Consider two cases:

1. Thermistor resistance is exactly 100 Ω.

2. Thermistor resistance changes from

200 Ω to 100 Ω.

R =100WL

+

-9V=VS

R

I

3.2.8 Current Divider Circuit

Problem 3.50. For the circuit shown in the

following figure:

A. Calculate the voltage between terminals

a and b. Show its polarity on the figure.

B. Use the current division principle to cal-

culate branch currents i1, i2.

3 A 1 M 1 M

a

b

i2i1

Problem 3.51. Find branch currents i1, i2 for

the circuit shown in the following figure:

i2i1

+

-10 V 1 kW 1 kW

Problem 3.52. Find branch currents i1, i2 for

the circuit shown in the following figure:

i2i1

3 kW 5 kW10mA

Problem 3.53. Find the voltage between termi-

nals a and b (voltage across the current power

source) for the circuit shown in the following

figure:

5 kW

1 W

5 kW

1 kW1 kW

3A

a

b

Problem 3.54. The voltage source in the circuit

is delivering 0.2 W of electric power. Find R.

+

-10 V

1 kW

RR

Chapter 3 Circuit Laws and Networking Theorems

III-134](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-153-320.jpg)

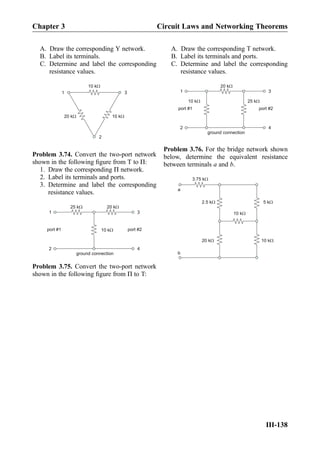

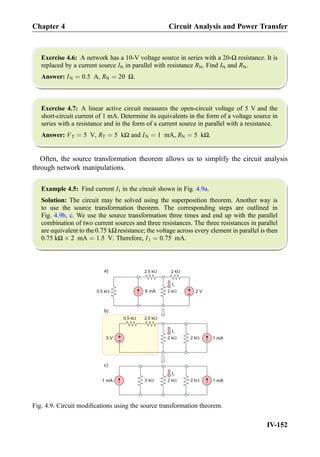

![Example 4.6: The circuit in Fig. 4.10a includes a current-controlled voltage source with

the strength of 4000ix [V]. Find current ix using the source transformation.

Solution: The corresponding circuit transformation is shown in Fig. 4.10b. The circuit with

the current-controlled current source in Fig. 4.10b is solved using KCL and KVL. KCL

written for the bottom node states that the current of 3 mA þ 3ix flows through the

rightmost 1-kΩ resistance (directed down). Since, by KVL, the voltages across both resis-

tances must be equal, one has

3 mA þ 3ix ¼ ix ) ix ¼ À1:5 mA ð4:16Þ

Alternatively, one might convert the independent current source to the independent voltage

source. However, this method would hide ix.

4.2.4 Thévenin’s and Norton’s Theorems: Proof Without Dependent

Sources

The origin of The´venin’s theorem is due to Léon Charles Thévenin, a French engineer

(1857–1926). The theorem is illustrated in Fig. 4.11a, b and can be expressed in the

following form:

1. Any linear network with independent voltage and current sources, dependent linear

sources, and resistances, as shown in Fig. 4.11a, can be replaced by a simple

equivalent network: a voltage source VT in series with resistance RT.

2. The equivalent network in Fig. 4.11b is called the The´venin equivalent.

3. Voltage VT is the open-circuit voltage VOC of the original network.

4. When dependent sources are not present, Thévenin resistance RT is an equivalent

resistance Req of the original network with all independent sources turned off

(voltage sources are replaced by short circuits and current sources by open circuits).

5. When both dependent and independent sources are present, the independent sources

are not turned off. Resistance RT is given by RT ¼ VOC=ISC, where ISC is the short-

circuit current of the original network.

a)

3 mA 1 kW

1 kW

b)

+

- 4000ix

ix

3 mA 1 kW 4ix

ix

1 kW

Fig. 4.10. Using source transformation for a circuit with dependent sources.

Chapter 4 Section 4.2: Generator Theorems

IV-153](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-172-320.jpg)

![Exercise 8.7: Three impedances j5Ω, 10Ω, 10Ω are combined in parallel. What is the

equivalent impedance?

Answer: 2:5 þ j2:5 Ω.

Exercise 8.8: In Fig. 8.18, the impedance of the capacitor changes toÀj10Ω. What will be

the phasor current, I, through the capacitor?

Answer: I ¼ 1∠90

A½ Š

8.3.4 Thévenin and Norton Equivalent Circuits

The The´venin’s theorem for steady-state AC circuits is formulated as follows. Any linear

AC network of resistors/capacitors/inductors and voltage/current power sources operat-

ing at the same frequency can be represented in the form of a Thévenin

equivalent network shown in Fig. 8.19b (phasor form). This result is a direct extension

of Thévenin’s theorem for DC circuits stated in Chapter 4. Thévenin’s theorem allows us

to reduce complicated AC circuits to a simple source and the impedance configuration,

with the same power output to a load. The AC frequency remains the same. Phasor

voltage VT is known as The´venin voltage or simply the source voltage; impedance ZT is

called The´venin impedance or source impedance. The phasor voltage may have

10

I

V1

+

-

j10

10 - 5j[A]90

Fig. 8.18. Source transformation applied to the AC circuit from the previous figure.

+

-

10

V1

+

-

j10

10 - 5j[V]9010

Fig. 8.17. An AC circuit solved with the help of source transformation. Note that every impedance

box has a physical counterpart shown within this box.

Chapter 8 Section 8.3: Principles of AC Circuit Analysis

VIII-415](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-429-320.jpg)

![Summary

Term Meaning/Figure

Steady-state AC

voltage (steady-state

alternating current)

υ tð Þ ¼ Vm cos ωt þ φð Þ

Vm 0 is the voltage

amplitude [V]

ω ¼ 2πf 0 is the angular

frequency [rad/s]

f 0 is the frequency [Hz]

T ¼ 1=f 0 is the period [s]

Àπ φ π is the phase

[rad] or [deg]

Leading/lagging

Euler’s identity e jα

¼ cos α þ j sin α, e jπ=2

¼ j, eÀjπ=2

¼ Àj

Time-domain

signal υ(t) versus

its phasor V; phasor

diagram

Complex phasors

and impedances

ZR ¼ R

ZC ¼

1

jωC

ZL ¼ jωL

(continued)

Chapter 8 Summary

VIII-419](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-433-320.jpg)

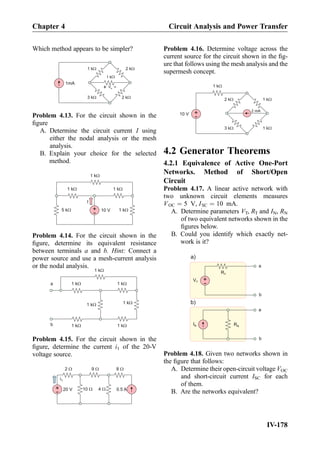

![Problem 8.46. Phasor voltages and currents

for three unknown circuit elements are shown

in the figure below. Determine the type of

the element (R, L, or C) and the value of R,

L, or C.

0 1

I

V

2

1

2

3

a)

0 1

I

V

2

1

2

3

b)

=1000 rad/sec

=3000 rad/sec

0 1

I

V

2

1

2

3

c) =20000 rad/sec

Re (V or A)

Im (V or A)

Re (V or A)

Im (V or A)

Re (V or A)

Im (V or A)

Problem 8.47. Phasor voltages and phasor cur-

rents for three unknown circuit elements are

shown in the figure below. Determine the type of

the element (R, L, or C) and the value of R, L, or

C when appropriate.

0

Re (V or A)

1I

V

2

1

2

3

a)

0 1

I

V

2

1

2

3

b)

=1000 rad/sec

=3000 rad/sec

0 1I V2

1

2

3

c) =20000 rad/sec

Im (V or A)

Re (V or A)

Im (V or A)

Re (V or A)

Im (V or A)

Problem 8.48*. The following MATLAB

script plots the real-valued signals in

time domain corresponding to the phasor

voltage V ¼ 5∠30

V½ Š and to the phasor

current I ¼ 2∠ À 60

A½ Š for an inductor.

clear all

f ¼ 2e6; % frequency, Hz

T ¼ 1/f; % period, sec

dt ¼ T/100; % sampling int.

t ¼ [0:dt:2.5*T]; % time vector

vL ¼ 5*cos(2*pi*f*t+pi/6); % voltage

iL ¼ 2*cos(2*pi*f*t-pi/3); % current

t ¼ t/T; % time in periods

Chapter 8 Problems

VIII-429](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-443-320.jpg)

![Example 9.2 (cont.):

Vm = [10 10 10]; % input voltage amplitudes, V

f = [20 3000 20000]; % input voltage frequencies, Hz

omega = 2*pi*f; % angular frequencies, rad/sec

R = 100; % resistance, Ohm

C = 530e-9; % capacitance, F

tau = R*C;

VmC = 1./sqrt(1+(omega*tau).^2).*Vm % output voltage ampl., V

phiC = - atan(omega*tau)*180/pi % output phases in deg

Exercise 9.1: The input voltage to a high-pass filter circuit is a combination of two

harmonics, υin tð Þ ¼ 2 cos ω1 t þ 2 cos ω2 t, with the amplitude of 2 V each. The filter has

the following parameters: R ¼ 100 kΩ and C ¼ 1:59 nF. Determine the output voltage

υout(t) to the filter given that f 1 ¼ 100 Hz and f 2 ¼ 100 kHz.

Answer: υout tð Þ ¼ 1:99 cos ω1 t À 5:7

ð Þ þ 0:02 cos ω2 t À 89:4

ð Þ V½ Š.

Application Example: Effect of a Load Connected to the Filter

The initial excitement about the simplicity of the theoretical filter model often fades

quickly once we try to construct the filter circuit of Fig. 9.2a or Fig. 9.2b in the laboratory.

And the circuit does not work. The major reason for this is the effect of a load connected

to the filter. We consider the low-pass filter in Fig. 9.3.

To solve the circuit with the load, we need to apply the phasor method. The input

voltage is now divided between the resistance R and the parallel combination of the

capacitor impedance and the load resistance, RL. Instead of Eq. (9.1c), we will have

VC ¼

1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1 þ R=RLð Þ2

þ ωτð Þ2

q Vm∠φC V½ Š, φC ¼ À tan À1 ωτ

1 þ R=RL

ð9:4Þ

The proof of this result is suggested in Problems 9.5 and 9.6. The necessary condition for

proper filter operation (both high pass or low pass) is that the filter termination resistance

R

C

+

-

v (t)outv (t)in

+

-

Load

Fig. 9.3. A generic load connected to the low-pass RC filter.

Chapter 9 Section 9.1: First-Order Filter Circuits and Their Combinations

IX-439](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-453-320.jpg)

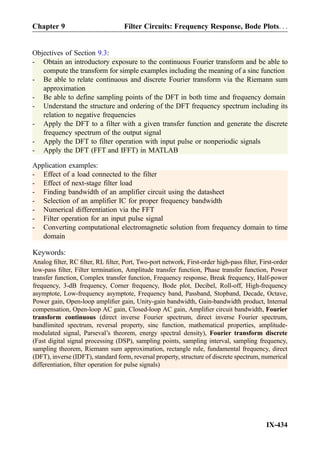

![frequency excites internal resonances, similar to a mechanical mass-spring system, that

continue ad infinitum.

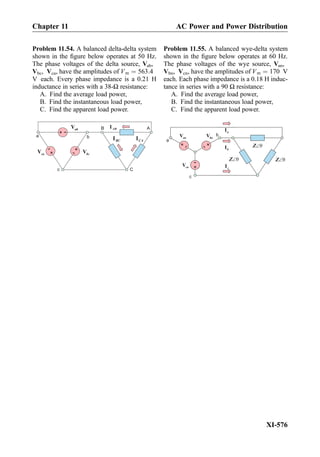

9.2.2 Unity-Gain Bandwidth Versus Gain-Bandwidth Product

The amplifier gain in Fig. 9.11 decreases by a factor of 0.1 (or 20 dB) gain roll-off per

frequency decade. The decay already starts at a relatively low break frequency of 10 Hz

where the DC open-loop gain drops by the factor of 0.707 or 1=

ffiffiffi

2

p

. The corresponding

value in dB is 20log101=

ffiffiffi

2

p

¼ À3 dB. The gain continues to decrease further and

reaches unity at the frequency of 1 MHz. This frequency is equal to the unity-gain

bandwidth (BW) of the amplifier, i.e., for the amplifier IC depicted in Fig. 9.11:

BW ¼ 1 MHz ð9:12Þ

A remarkable observation from Fig. 9.11 is that the gain-bandwidth product (sometimes

denoted by GBWor GB in datasheets) remains constant over the band for every particular

gain value. The gain-bandwidth product is equal to the length of every single arrow

(in Hz) in Fig. 9.11 times the corresponding gain value (dimensionless), that is,

f ¼ 102

Hz ) GBW ¼ 102

104

¼ 106

Hz ¼ BW,

f ¼ 103

Hz ) GBW ¼ 103

103

¼ 106

Hz ¼ BW,

f ¼ 104

Hz ) GBW ¼ 104

102

¼ 106

Hz ¼ BW;

ð9:13Þ

etc. Thus, the gain-bandwidth product is exactly equal to the unity-gain bandwidth BW;

it is frequently specified in the manufacturer datasheet. In what follows, we will use the

unity-gain bandwidth as the major parameter of interest. Note that instead of, or along

Open-loopgain,AOL

105

104

103

102

101

1

106

1 102

103

101

104

105

106

107

Frequency of input voltage, Hz

Open-loopgain[dB],20log10

(AOL)

100

80

60

40

120

20

0

3dB or 0.707A (0)OL

20 dB per decade

roll-off

BWfb

Fig. 9.11. Bode plot of the open-loop gain magnitude for the LM741-type amplifier IC. Note the

logarithmic scale on the left and the corresponding scale in dB on the right. The frequency

bandwidth given by the break frequency fb is only 10 Hz.

Chapter 9 Filter Circuits: Frequency Response, Bode Plots. . .

IX-452](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-466-320.jpg)

![Example 9.11: An inverting amplifier with a gain of À20 and bandwidth of at least

20 kHz is needed. Is the LM348 chip appropriate for this purpose?

Solution: From the LM348 datasheet, we obtain BW ¼ 1 MHz. Because the inverting

gain is À20, we should use a ratio of R2=R1 ¼ 20. According to Eq. (9.22), this gives

f closed loop

b ¼ 47:6 kHz. The closed-loop 3-dB bandwidth of the amplifier coincides with

this value. Therefore, the LM348 chip is sufficient for our purposes. However, if its gain is

forced to a higher value, say to 100, then the useful bandwidth reduces to 10 kHz.

Exercise 9.7: A non-inverting amplifier with a gain of 31 and a bandwidth of at least

90 kHz is needed. Is an LM741-based amplifier IC appropriate for this circuit?

Answer: No.

10

5

10

4

10

3

10

2

10

1

1

10

6

1 10

2

10

3

10

1

10

4

10

5

10

6

10

7

Frequency of input voltage, Hz

Open-loopgainvs.closed-loopgain[dB]

100

80

60

40

120

20

0

20 dB per decade

roll-off

fb

3dB or 0.707G

Open-loopgainvs.closed-loopgain

3dB or 0.707A (0)OL

open-loop gain

closed-loop gain

closed-loop bandwidth

fb

closed loop

a)

b)

Fig. 9.13. Closed-loop AC gain ACL( f ) (lower curve) versus open-loop AC gain AOL( f ) (upper

curve) for an inverting amplifier with AOL 0ð Þ ¼ 105

and 1 þ R2=R1 ¼ 10 (the amplifier DC gain

is À9).

Chapter 9 Section 9.2: Bandwidth of an Operational Amplifier

IX-457](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-471-320.jpg)

![f tnð Þ ¼

1

NΔT

XNÀ1

m¼0

e j

2π

N mnF ωmð Þ, n ¼ 0, . . . , N À 1 ð9:33Þ

Definition of Discrete Fourier Transform

It is rather inconvenient to keep the factor ΔT in both Eqs. (9.32) and (9.33), respectively.

Therefore, we may introduce the notation

f n½ Š ΔTf tnð Þ, F m½ Š F ωmð Þ ð9:34Þ

and obtain the standard form of the discrete Fourier transform

F m½ Š ¼

XNÀ1

n¼0

eÀj

2π

N mnf n½ Š, m ¼ 0, . . . , N À 1 ð9:35aÞ

f n½ Š ¼

1

N

XNÀ1

m¼0

e j

2π

N mnF m½ Š, n ¼ 0, . . . , N À 1 ð9:35bÞ

Here, f [n] may be treated as an impulse having the area of ΔTf(tn).

Exercise 9.10: Establish a relation betweenF N À m½ Šand F[m] for a real signal f(t), which

is called a reversal property of the discrete Fourier transform.

Answer:

F*

N À m½ Š ¼ F m½ Š ð9:36Þ

where the star again denotes complex conjugate.

Example 9.13: It is possible to very significantly minimize the actual number of multi-

plications necessary to compute a given DFT in Eqs. (9.35a, b). The DFT so constructed is

the fast Fourier transform (FFT) and inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT). It works best

when N is a power of two. For a pulse f tð Þ ¼ exp À2 t À 5ð Þ2

, 0 s t 10 s, compute

its FFT and then the IFFT and finally compare the end result with the original pulse form

given that N ¼ 64.

Solution: The solution is conveniently programmed using a few lines of a self-explanatory

MATLAB code, which uses Eq. (9.29) and plots two final curves:

Chapter 9 Filter Circuits: Frequency Response, Bode Plots. . .

IX-462](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-476-320.jpg)

![Example 9.13 (cont.):

T = 10; N = 64;

dT = T/N; t = dT*(0:N-1);

f0 = exp(-2*(t-5).^2);

F = fft(f0); f = ifft(F);

plot(t, f, t, f0, '*');

Both curves are virtually identical: the relative integral error (integral of signal difference

magnitude over the integral of signal magnitude) does not exceed 10À16

.

Structure of Discrete Fourier Spectrum

The set of spectrum values F[m], m ¼ 0, . . . , N À 1, of the DFT has an important

redundancy property illustrated in the following example.

Example 9.14: Express all discrete Fourier spectrum values F[m] present in Eq. (9.35a)

through N/2 first values of F[m] only. Hint: Use Eq. (9.36).

Solution:

F 0½ Š, F 1½ Š, . . . , F

N

2

À 1

!

, F

N

2

!

, F

N

2

þ 1

!

, . . . , F N À 1½ Š ¼

F 0½ Š, F 1½ Š, . . . , F

N

2

À 1

!

, F

N

2

!

, F* N

2

À 1

!

, . . . , F*

1½ Š

ð9:37Þ

Equation (9.37) demonstrates how the output of the DFT (and of the FFT, in particular in

MATLAB) is arranged in reality. It is a symmetric conjugate aboutm ¼ N=2. Equation (9.37)

is a key to finding derivatives and arbitrary filter transformations of the input signal with the

FFT. Only a frequency with m N=2 is considered to be valid; its mirror reflection about

m ¼ N=2 is a higher “aliasing frequency.” We emphasize that, according to Eq. (9.26), the

complex conjugates may be replaced by spectrum values at a negative frequency, i.e.,

F*

1½ Š ¼ F À1½ Š. Thus, the spectrum above m ¼ N=2 corresponds to negative frequencies

with m ÀN=2.

9.3.4 Sampling Theorem

It follows from Example 9.14 that only frequency samples with ωm

N

2 ω0 are really

needed. This fact is a consequence of the sampling theorem, which states that any signal

bandlimited to ωmax can be reproduced exactly using the discrete Fourier transform if

ωmax

N

2

ω0 ð9:38aÞ

Chapter 9 Section 9.3: Introduction to Continuous and Discrete. . .

IX-463](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-477-320.jpg)

![Example 9.15 (numerical differentiation via the FFT) (cont.):

T = 10; N = 64;

dT = T/N; t = dT*(0:N-1);

f = exp(-2*(t-5).^2); % input pulse

omega = (2*pi/T)*[0:N/2]; % non-aliasing frequencies

H = j*omega; % H at non-aliasing frequencies

F = fft(f); % FFT spectrum

HF = F.*[H, conj(H(end-1:-1:2))]; % HF according to Eq. (9.40)

fder = real(ifft(HF)); % numerical derivative

fder0 = -4*(t-5).*f; % analytical derivative

plot(t, fder0, t, fder, 'd'); % compare both derivatives

Both curves are virtually identical: the relative integral error (integral of signal difference

magnitude over the integral of analytical signal magnitude) does not exceed 1.3 Â 10À15

.

9.3.7 Application Example: Filter Operation for an Input Pulse Signal

The filter operation for an input pulse signal exactly follows Example 9.15 but with a

different transfer function H(ω).

Example 9.16: A pulse f tð Þ ¼ exp À2 t À 5ð Þ2

, 0 s t 10 s is an input to a first-

order high-pass filter. Find the filter output when its (angular) break frequency is given by

a) ω0 ¼ 1 rad=s and b) ω0 ¼ 10 rad=s. Use the FFT and IFFT with N ¼ 64.

Solution: The solution is performed and programmed exactly described in the previous

example, but the transfer function is now given by Eq. (9.1b):

H ¼ j*omega/omega0./(1+j*omega/omega0);

t, s 10

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

df(t)/dt

0 5

Fig. 9.16. Analytical (solid curve) and numerical (diamonds) differentiation of the original

Gaussian pulse.

Chapter 9 Filter Circuits: Frequency Response, Bode Plots. . .

IX-466](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-480-320.jpg)

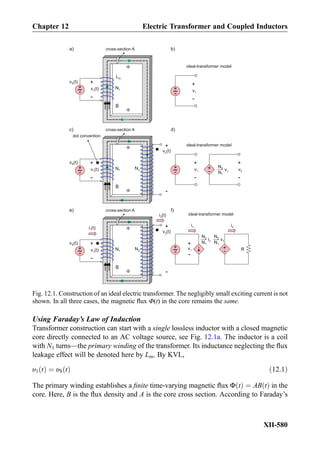

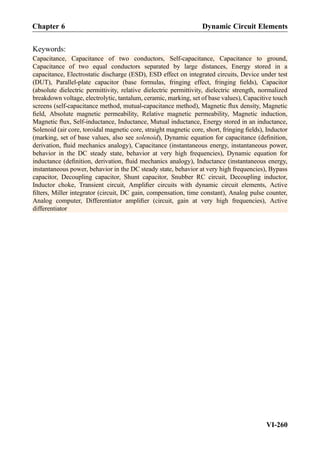

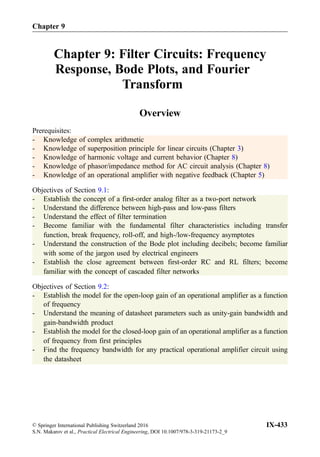

![Summary

Property First-order low-pass filter First-order high-pass filter

Circuit schematic

Transmission at

f ¼ 0 (DC)

1

(DC path through the resistor)

0

(No DC path)

Transmission at

f ! 1

0

(Inductor is an open circuit

at f ! 1)

1

(DC path through the resistor)

Transfer function

H( f )

1

1 þ j f =f bð Þ

f =f bð Þ

1 þ j f =f bð Þ

Decibels of H ¼ Hj j 20 log10H [dB] 20 log10H [dB]

Decibels of 1 and 0.1 0 dB and À20 dB 0 dB and À20 dB

Transfer function

magnitude Hm( f )

1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1 þ f =f bð Þ2

q

f =f b

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1 þ f =f bð Þ2

q

Transfer function

phase ∠φH

∠ À tan À1 f

f b

π

2

À tan À1 f

f b

Break frequency,

(half-power fre-

quency, 3-dB

frequency, corner

frequency)

f b ¼

1

2πτ

Hz½ Š

τ ¼ RC or

L

R

s½ Š

f b ¼

1

2πτ

Hz½ Š

τ ¼ RC or

L

R

s½ Š

Passband (3 dB

bandwidth), Hz

From 0 to fb From fb to 1

Filter with a resistive

load RL

(continued)

Chapter 9 Summary

IX-469](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-483-320.jpg)

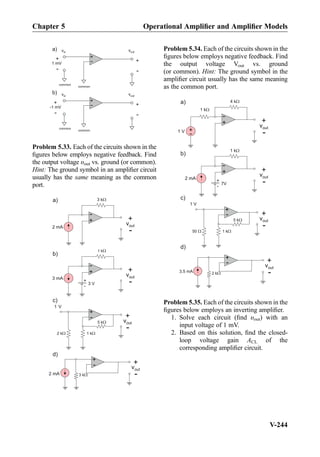

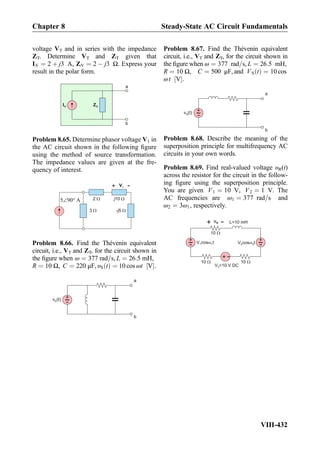

![Problems

9.1 First-Order Filter

Circuits and Their

Combinations

9.1.1 RC Voltage Divider as an Analog

Filter

Problem 9.1

A. Explain the function of an analog RC

filter.

B. Write the capacitor and resistor voltages

υR(t) and υC(t) of the series RC circuits

in the general form, as functions of the

AC angular frequency.

C. Which circuit element (or which voltage)

dominates at low frequencies? At high

frequencies?

Problem 9.2

A. Draw a schematic of the low-pass analog

RC filter. Show the input and output

ports.

B. Repeat the same task for the high-pass

analog RC filter.

Problem 9.3. The input voltage to the filter

circuit shown in the following figure is a com-

bination of two harmonics,

υin tð Þ ¼ 1 cos ω1 t þ 1 cos ω2 t, with the ampli-

tude of 1 V each. The filter has the following

parameters: R ¼ 100 kΩ and C ¼ 1:59 nF.

Determine the output voltage υout(t) to the filter

given that f 1 ¼ 100 Hz and f 2 ¼ 100 kHz.

Express all phase angles in degrees.

R

C

+

-

v (t)outv (t)in

+

-

Problem 9.4. Repeat the previous problem

for the filter circuit shown in the

following figure. All other parameters remain

the same.

C

R

+

-

v (t)in

+

-

v (t)out

Problem 9.5. The input voltage to the RC

filter circuit shown in the figure is

Vin tð Þ ¼ 5 cos ωt V½ Š. The filter has the fol-

lowing parameters: C ¼ 1 μF and

R ¼ 100 Ω. The filter operates in the fre-

quency band from 100 Hz to 50 kHz. The filter

is connected to a load with the load resistance

of 1 MΩ. By solving the corresponding AC

circuit, determine the output voltage amplitude

across the load (and its percentage versus the

input voltage amplitude) with and without the

load at f ¼ 100 Hz, f ¼ 1592 Hz, and

f ¼ 50 kHz.

R

C

+

-

v (t)outv (t)=5cos(wt) [V]in

+

-

Load

Problem 9.6. Repeat the previous problem

when the load resistance changes from 1 MΩ

to 100 Ω (decreases).

Problem 9.7. Repeat Problem 9.5 for the filter

circuit shown in the following figure. Assume

the load resistance of 100 Ω.

R

C

+

-

v (t)outv (t)=5cos( t) [V]in w

+

-

Load

Chapter 9 Problems

IX-473](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-487-320.jpg)

![C. Compute equivalent frequency samples

using negative frequencies.

D. Compute all discrete samples f [n].

E. Compute all discrete samples F[m] using

the definition of the discrete Fourier

transform. Explain the physical meaning

of their values.

F. Repeat the previous step using function

fft of MATLAB. Compare both sets of

F[m].

G. Restore all discrete samples f [n] using

the definition of the inverse discrete Fou-

rier transform. Compare them with the

exact function values.

H. Repeat the previous step using function

ifft of MATLAB. Compare both sets of

f [n].

Problem 9.58. Repeat the previous problem for

the signal f tð Þ ¼ cos t. All other parameters

remain the same.

Problem 9.59. For Problem 9.57, establish and

prove a discrete version of Parseval’s theorem

formulated in Problem 9.55.

Problem 9.60. An input signal to a filter has a

discrete frequency spectrum

F m½ Š, m ¼ 0, . . . , N À 1 computed via the

FFT. You are given filter transfer function

H computed at N

2 þ 1 frequency points of the

FFT, H m½ Š, m ¼ 0, . . . , N=2. Compute the

discrete spectrum of the filter’s output to be

fed into the IFFT.

9.3.6 Application Example: Numerical

Differentiation via the FFT

9.3.7 Application Example: Filter Oper-

ation for an Input Pulse Signal

Problem 9.61*. Present the text of a MATLAB

script that numerically differentiates the input

signal f tð Þ ¼ sin t over the time interval from

0 to 4π s using the FFT with 4096 sampling

points and plot the resulting signal derivative.

Problem 9.62. Repeat the previous problem for

the signal f tð Þ ¼ exp À t À 2πð Þ2

. All other

parameters remain the same.

Problem 9.63. A monopolar pulse

f tð Þ ¼ exp À2 t À 5ð Þ2

, 0 t 10 s is

an input to a series combination of two identical

first-order high-pass filters. Find the output of

the filter combination when the (angular) break

frequency is given by:

A. ω0 ¼ 0:5 rad=s

B. ω0 ¼ 10 rad=s

Use the FFT and IFFT with N ¼ 64. Plot the

filter output and explain the output signal

behavior in every case.

Problem 9.64. A bipolar pulse

f tð Þ ¼ 5Àtð Þexp À2 t À5ð Þ2

, 0 t 10s is

an input to a first-order low-pass filter. Find the

filter output when its (angular) break frequency

is given by:

A. ω0 ¼ 0:5 rad=s

B. ω0 ¼ 5 rad=s

Use the FFT and IFFT with N ¼ 64. Plot the

filter output along with the input signal on the

same graph and explain the output signal

behavior in both cases.

Chapter 9 Filter Circuits: Frequency Response, Bode Plots. . .

IX-480](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-494-320.jpg)

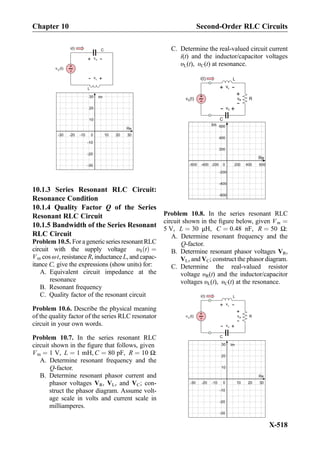

![resistance is small, large circuit current and large capacitor and inductor voltages may be

achieved at the resonance. You have to be aware of the fact that it is not uncommon to

measure voltage amplitudes of 50–500 Vacross the individual elements in the laboratory,

whereas the driving source voltage may only have an amplitude of 10 V. The circuit in

Fig. 10.4 is also called the series RLC tank circuit.

Exercise 10.2: In the series resonant RLC circuit shown in Fig. 10.4, Vm ¼ 10 V,

L ¼ 50 μH, C ¼ 0:5 nF, R ¼ 50 Ω. Determine the real-valued circuit current and the

inductor/capacitor voltages at the resonance.

Answer:

i tð Þ ¼ 0:2 cos ωtð Þ A½ Š, υL tð Þ ¼ 63:3 cos ωt þ 90

ð Þ V½ Š,

υC tð Þ ¼ 63:3 cos ωt À 90

ð Þ V½ Š:

ð10:7Þ

Could we increase the resonant voltage amplitudes of the series RLC circuit in

Fig. 10.4a [see Eq. (10.6c)] while keeping the voltage source and the circuit resistance

unaltered? Yes we can. However, one more concept is required for this and similar

problems: the concept of the quality factor of a resonator.

10.1.4 Quality Factor Q of the Series Resonant RLC Circuit

Multiple factors in front of resonant voltages and currents expressions can be reduced to

one single factor. Using the definition of the resonant frequency ω0, Eq. (10.6c) at the

resonance may be rewritten in the simple form

i tð Þ ¼

Vm

R

cos ω0tð Þ, υL tð Þ ¼ QVm cos ω0t þ90

ð Þ, υC tð Þ ¼ QVm cos ω0t À 90

ð Þ

ð10:8Þ

where the dimensionless constant

Q ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

L=R

p

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

RC

p ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

L=C

p

R

ð10:9Þ

is called the quality factor of the series resonant RLC circuit. The equivalent forms are

Q ¼

1

ω0RC

¼ ω0

L

R

ð10:10Þ

Thus, in order to increase the resonant voltage amplitudes in Eq. (10.8), we should simply

increase the quality factor of the resonator. Even if the circuit resistance remains the same,

we can still improve Q by increasing the ratio of L/C in Eq. (10.9). This observation

Chapter 10 Second-Order RLC Circuits

X-488](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-502-320.jpg)

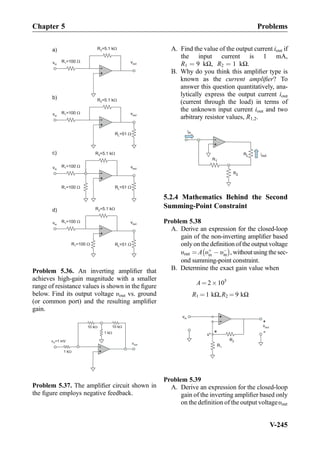

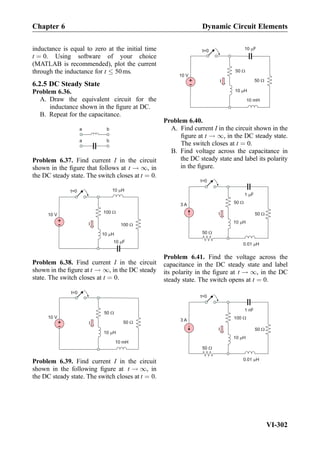

![Example 10.6: Create Bode plots as seen in Fig. 10.5 using MATLAB.

Solution: We create only one bandwidth curve, for Q ¼ 2. Other curves are obtained

similarly, using the command hold on.

f = logspace(3, 5, 101); % frequency vector, Hz(from 10^3 to 10^5 Hz)

f0 = 1e4; % resonant frequency, Hz

Q = 2; % quality factor, dimensionless

H = 1./sqrt(1+Q^2*(f/f0-f0./f).^2);

HdB = 20*log10(H);

semilogx(f, HdB, 'r'); grid on;

title('Bode plot');

xlabel('frequency, Hz'); ylabel('H, dB')

axis([min(f) max(f) -30 0])

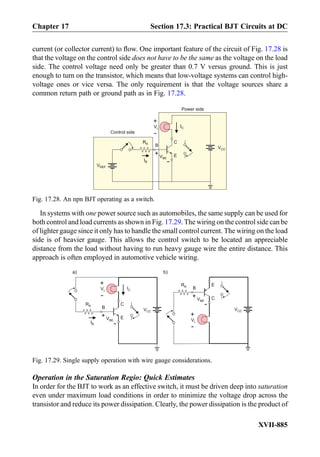

10.1.6 Parallel Resonant RLC Circuit: Duality

The parallel resonant RLC circuit is shown in Fig. 10.6. It is driven by an alternating

current source iS tð Þ ¼ Im cos ωt. The parallel RLC resonator is a current divider circuit,

which is the dual to the series RLC resonator (which is a voltage divider) in Fig. 10.4.

While the series RLC resonator is capable of creating large voltages (or “amplifying” the

supply voltage), the parallel RLC resonator circuit is capable of producing large currents.

The amplitudes of the currents through the inductor and the capacitor may be large, much

larger than the supply current itself. The circuit in Fig. 10.6 is also called the parallel RLC

tank circuit.

The circuit in Fig 10.6a is solved by using the phasor method; see Fig. 10.6b. The

equivalent impedance is given by

1

Zeq

¼

1

ZR

þ

1

ZL

þ

1

ZC

¼

1

R

þ

1

jωL

þ jωC ¼

1

R

À j

1 À LCω2

ωL

Ω½ Š ð10:18Þ

The resonance condition for any AC circuit states that the impedance Zeq must be a

purely real number at resonance. If the impedance is real, its reciprocal, the admittance, is

also real and vice versa. Therefore, from Eq. (10.18), we obtain the resonant frequency

R

i (t)S

LZ CZIS

V

+

-

b)a)

RZL C

i (t)S

+

-

v

+

-

v

+

-

v

+

-

v

IS

V

+

-V

+

-

Fig. 10.6. Parallel resonant RLC circuit and its phasor representation.

Chapter 10 Section 10.1: Theory of Second-Order Resonant RLC Circuits

X-493](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/practicalelectricalengineering-160720234734/85/Practical-electrical-engineering-507-320.jpg)