This document provides a handbook on poultry diseases covering various topics. It begins with an introduction and discusses economic considerations in disease prevention and control. It covers health and performance in tropical climates, prevention of disease through biosecurity, vaccination, nutrition, and control procedures for different production systems. It also discusses various disease categories in poultry like immunosuppressive, respiratory, multifactorial, systemic, enteric, locomotory, and integumentary diseases. For each disease, it provides information on etiology, transmission, clinical signs, pathology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

![10

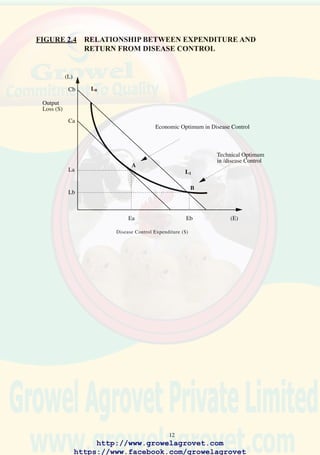

FIGURE 2.1 CONCEPTUAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COST AND

REVENUE

FIGURE 2.2 GENERAL FORMAT FOR GROSS MARGIN ANALYSIS

(1) Value of inventory at the beginning of the period

(2) Cost of chicks/flocks purchased

(3) Variable costs (feed, management, health care)

(4) Total value at the beginning of the period plus all costs

[ (1) + (2) + (3) ]

(5) Value of flock at the end of the period

(6) Value of chickens and products sold

(7) Revenue from by-products

(8) Total value at the end of the period

[ (5) + (6) + (7) ]

(9) Gross margin

[ (8) - (4)]

http://www.growelagrovet.com

https://www.facebook.com/growelagrovet](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poultrydiseaseshandbook-131025105224-phpapp01/85/A-Handbook-of-Poultry-Diseases-25-320.jpg)

![11

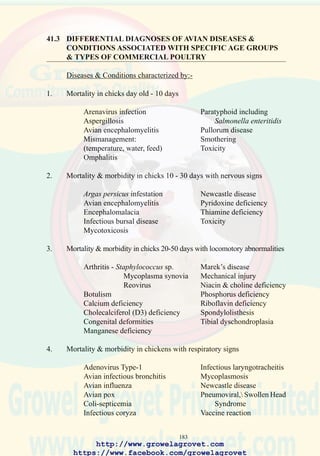

FIGURE 2.3 FORMAT OF PAY-OFF TABLE CONSIDERING

ALTERNATIVE PREVENTIVE STRATEGIES

Possible outcomes Probability Financial result of alternative

of strategies in designated

occurrence monetary unit ($)

no action biosecurity vaccination

#0 #1 #2

With disease X a b c

= 0.6 $3,000 $6,000 $8,000

Without disease (1 -X) d e f

= (1 - 0.6) = 0.4 $10,000 $7,000 $9,000

Expected monetary value associated with alternative strategies:

(Base #0) = (a x X) + [d x (1 - X)] = $5,800

$1,800 + $4,000

(Strategy #l) = (b x X) + [e x (1 - X)] = $6,400

$3,600 + $2,800

(Strategy #2) = (c x X) + [f x (1 - X)] = $8,400

$4,800 + $3,600

http://www.growelagrovet.com

https://www.facebook.com/growelagrovet](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poultrydiseaseshandbook-131025105224-phpapp01/85/A-Handbook-of-Poultry-Diseases-26-320.jpg)