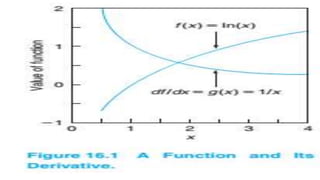

The document outlines the foundational postulates of quantum mechanics, stating that the Schrödinger equation does not encapsulate the entirety of the theory. It describes the relationship between wave functions, mechanical variables, and the corresponding mathematical operators, illustrating how measurements affect the state of a system. Additionally, the postulates emphasize the role of Hermitian operators and their associated properties in determining energy eigenvalues and expectation values in quantum mechanics.