This document discusses robot dynamics and Jacobians. It covers:

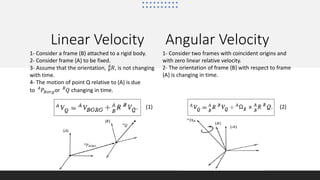

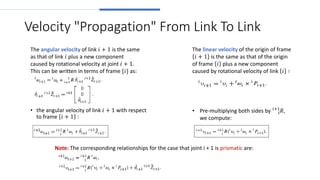

1) Linear and rotational velocity of rigid bodies and how velocity propagates from link to link in a robot.

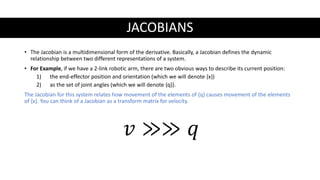

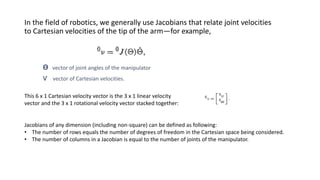

2) Jacobians relate how movement of joint angles causes movement of the end effector position and orientation.

3) Singularities occur when a robot loses degrees of freedom in Cartesian space.

4) Static forces in manipulators are analyzed by considering forces and torques exerted between links.