The document summarizes algorithms for learning first-order logic rules from examples, including:

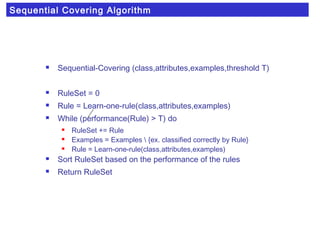

1) A sequential covering algorithm that learns one rule at a time to cover examples, removing covered examples and repeating until all examples are covered or rules have low performance.

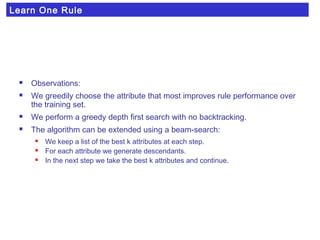

2) The learn-one-rule sub-algorithm uses a decision tree-like approach to greedily select the attribute that best splits examples according to a performance metric.

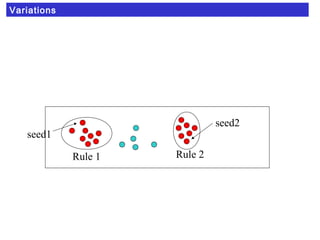

3) Variations include allowing low probability classes and using a seed example approach instead of removing covered examples between rules.

![STAR (Michalsky)

venenoso(X) <- color(X,

[marron,verde])

forma(X,alargado)

tierra(X,humeda)

bajo_arbol(X,Y) arbol(Y,

[fresno,laurel])

venenoso(X) <- color(X,

[marron,verde])

forma(X,alargado)

tierra(X,humeda)

bajo_arbol(X,Y) arbol(Y,

[fresno,laurel])

venenoso(X) <-

forma(X,alargado)

tierra(X,humeda)

ambiente(X,humedo)

venenoso(X) <-

forma(X,alargado)

tierra(X,humeda)

ambiente(X,humedo)

venenoso(X) <-

color(X,marron)

forma(X,alargado)

tierra(X,humeda)

ambiente(X,humedo)

bajo_arbol(X,Y) arbol(Y,Z)

venenoso(X) <-

color(X,marron)

forma(X,alargado)

tierra(X,humeda)

ambiente(X,humedo)

bajo_arbol(X,Y) arbol(Y,Z)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poggi-analytics-star-1a-160719004324/85/Poggi-analytics-star-1a-12-320.jpg)

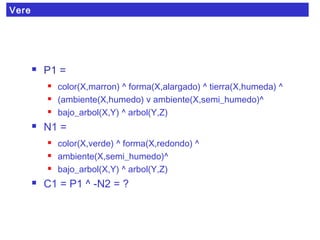

![Vere

C1 = P1 ^ -N2 =

color(X,marron) ^ forma(X,alargado) ^ tierra(X,humeda) ^

(ambiente(X,humedo) v ambiente(X,semi_humedo)^

bajo_arbol(X,Y) ^ arbol(Y,Z) ^

- [ color(X,verde) ^ forma(X,redondo) ^

ambiente(X,semi_humedo) ^

bajo_arbol(X,Y) ^ arbol(Y,Z) ]

=

color(X,marron) ^ forma(X,alargado) ^ tierra(X,humeda) ^

(ambiente(X,humedo) v ambiente(X,semi_humedo) ^

bajo_arbol(X,Y) ^ arbol(Y,Z) ^

-color(X,verde) ^ -forma(X,redondo) ^

-ambiente(X,semi_humedo) ^

- bajo_arbol(X,Y) ^ - arbol(Y,Z)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/poggi-analytics-star-1a-160719004324/85/Poggi-analytics-star-1a-17-320.jpg)