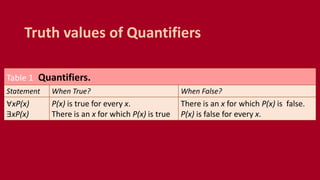

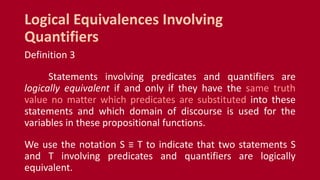

This document discusses predicates and quantifiers in predicate logic. Predicate logic can express statements about objects and their properties, while propositional logic cannot. Predicates assign properties to variables, and quantifiers specify whether a predicate applies to all or some variables in a domain. There are two types of quantifiers: universal quantification with ∀ and existential quantification with ∃. Quantified statements involve predicates, variables ranging over a domain, and quantifiers to specify the scope of the predicate.

![“Every student in class has studied calculus.”

What if we change the domain to consist of all people?

“For every person x, if person x is a student in this class

then x has studied calculus.”

If S(x) represents the statement that person x is in this

class: ∀x(S(x) → C(x))

[Note: not ∀x(S(x) ∧ C(x)) because this statement says that all

people are students in this class and have studied calculus!]

2nd Solution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cmsc56lec3-190425080743/85/CMSC-56-Lecture-3-Predicates-Quantifiers-80-320.jpg)