Here is a limerick I wrote following the form:

There once was a poet named Claire

Who loved writing poems with flair

But one day she found

Her rhymes weren't so sound

So back to the form books she'd fare

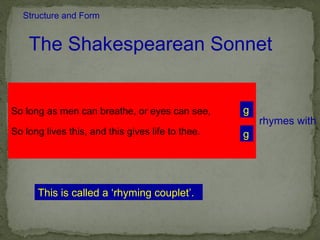

Structure and Form

The Shakespearean Sonnet

The Shakespearean, or English, sonnet has 14 lines with a rhyme scheme of:

ABAB CDCD EFEF GG

It is divided into 3 quatrains (groups of 4 lines) and a rhyming couplet at the end.

Let's look at an example sonnet by William Shakespeare to see how this form works:

Shall I compare thee to a