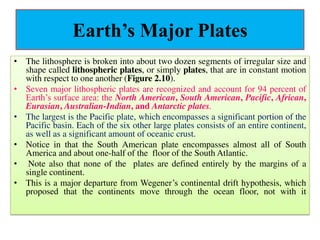

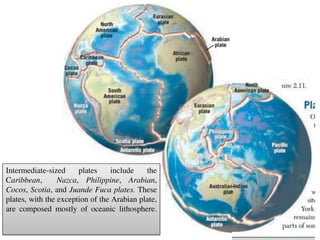

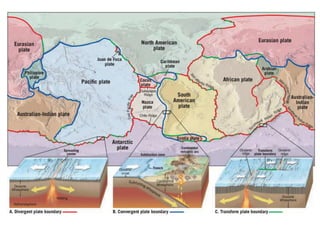

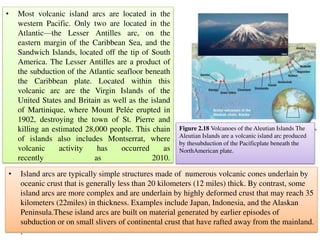

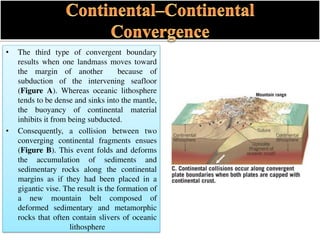

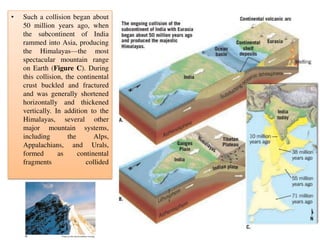

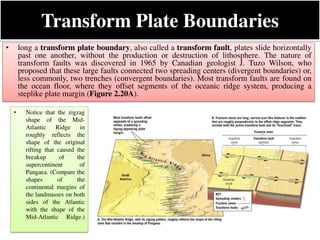

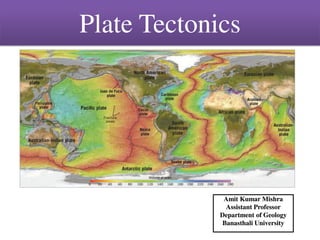

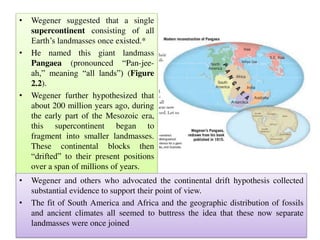

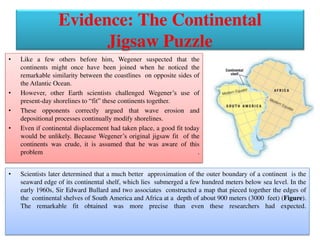

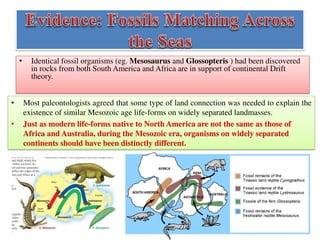

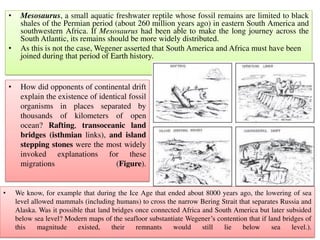

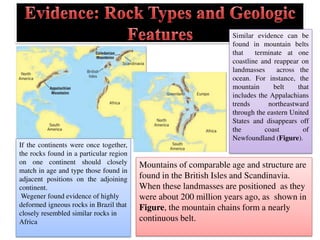

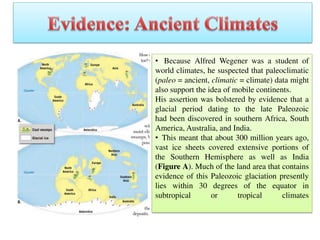

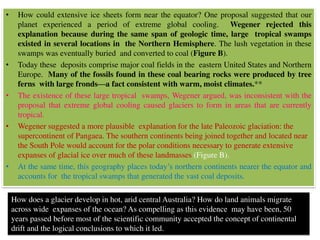

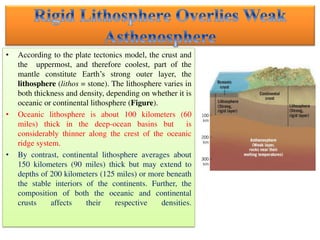

The document discusses plate tectonics and the evidence that supports the theory. It describes how Alfred Wegener first proposed the idea of continental drift in 1915, noting that continents seem to fit together. Over decades, further evidence was collected from matching fossil records, mountain ranges, and coastline shapes between separated continents. In the 1960s, the theory of plate tectonics emerged to explain these observations, proposing that the Earth's lithosphere is broken into plates that move over Earth's asthenosphere. There are three types of plate boundaries - divergent where new crust forms, convergent where plates collide, and transform where plates slide past each other.

![• The asthenosphere (asthenos = weak) is a hotter, weaker region in the

mantle that lies below the lithosphere). The temperatures and pressures in

the upper asthenosphere (100 to 200 kilometers [60 to 125 miles] in

depth) are such that rocks at this depth are very near their melting

temperatures and, hence, respond to forces by flowing, similar to the way

a thick liquid would flow.

• By contrast, the relatively cool and rigid lithosphere tends to respond to

forces acting on it by bending or breaking but not flowing.

• Because of these differences, Earth’s rigid outer shell is effectively

detached from the asthenosphere, which allows these layers to move

independently .

• Oceanic crust is composed of basalt, rich in dense iron and magnesium,

whereas continental crust is composed largely of less dense granitic

rocks. Because of these differences, the overall density of oceanic lithosphere

(crust and upper mantle) is greater than the overall density of continental

lithosphere.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/platetectonics2017-170927084221/85/Plate-tectonics-13-320.jpg)