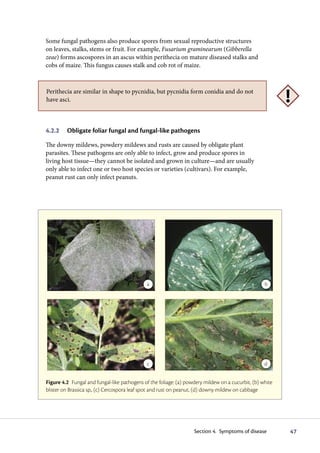

The diagnostic process begins with observing symptoms on plants, which can provide clues to the potential pathogens involved. Common symptoms like wilting, yellowing and stunting can have many causes. Specific symptoms like root galls help identify certain pathogens. A single plant may show symptoms from multiple pathogens. Accurate diagnosis may require laboratory analysis. It is important to carefully examine all plant parts and not guess the cause, as an incorrect diagnosis could impact treatment options.

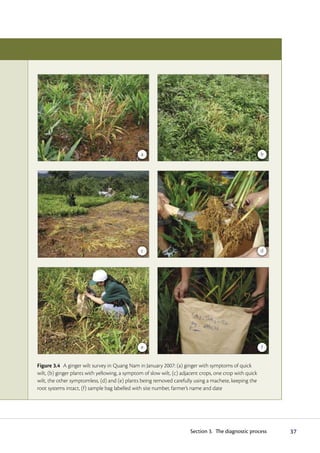

![c

a

b d e

f g h

Figure 4.4 Diseases of the crown, roots and stem: (a) club root of crucifers, (b) wilting of crucifers

(healthy [left] and diseased [right]) caused by club root (Plasmodiophora brassicae), (c) Fusarium wilt

of asters (note the production of sporodochia on the stem), (d) spear point caused by Rhizoctonia sp.,

(e) Phytophthora root rot of chilli, (f) Phytophthora root rot of chilli causing severe wilt, (g) Pythium root

and pod rot of peanuts, (h) perithecia of Gibberella zeae causing stalk rot of maize

50 Diagnostic manual for plant diseases in Vietnam](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plantdisease-120216150043-phpapp02/85/Plant-disease-19-320.jpg)