Instrumentation Limited (IL) is an Indian government enterprise established in 1964 to achieve self-reliance in control and automation technology for process industries. IL manufactures and supplies advanced control equipment on a turnkey basis to various industry sectors. It has manufacturing facilities in Kota and Palakkad, India and a network of offices across India to provide installation, commissioning and after-sales services. With over 45 years of experience, IL designs, engineers, manufactures, integrates, installs and commissions complex control systems and has diversified into various related fields to offer a comprehensive range of products and services.

![Page | 19

1. Schematic capture through an Electronic design automation tool.

2. Card dimensions and template are decided based on required circuitry and case of the PCB.

Determine the fixed components and heat sinks if required.

3. Deciding stack layers of the PCB. 1 to 12 layers or more depending on design complexity.

Ground plane and power plane are decided. Signal planes where signals are routed are in top

layer as well as internal layers.[31]

4. Line impedance determination using dielectric layer thickness, routing copper thickness and

trace-width. Trace separation also taken into account in case of differential signals. Microstrip,

stripline or dual stripline can be used to route signals.

5. Placement of the components. Thermal considerations and geometry are taken into account.

Vias and lands are marked.

6.Routing the signal traces. For optimal EMI performance high frequency signals are routed in

internal layers between power or ground planes as power planes behave as ground for AC.

7. Gerber file generation for manufacturing.

In the design of the PCB artwork, a power plane is the counterpart to the ground plane and

behaves as an AC signal ground, while providing DC voltage for powering circuits mounted on

the PCB. In electronic design automation (EDA) design tools, power planes (and ground planes)

are usually drawn automatically as a negative layer, with clearances or connections to the plane

created automatically.

4.1COPPERTHICKNESS

Copper thickness of PCBs can be specified in units of length, but is often specified as weight of

copper per square foot, in ounces, which is easier to measure. Each ounce of copper is

approximately 1.4 mils (0.0014 inch) or 35 μm of thickness.

The printed circuit board industry defines heavy copper as layers exceeding 3 ounces of copper,

or approximately 0.0042 inches (4.2 mils, 105 μm) thick. PCB designers and fabricators often

use heavy copper when design and manufacturing circuit boards in order to increase current-

carrying capacity as well as resistance to thermal strains.

Heavy copper plated vias transfer heat to external heat sinks. IPC 2152 is a standard for

determining current-carrying capacity of printed circuit board traces](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/projectreport-copy-150901073452-lva1-app6891/75/PCB-19-2048.jpg)

![Page | 26

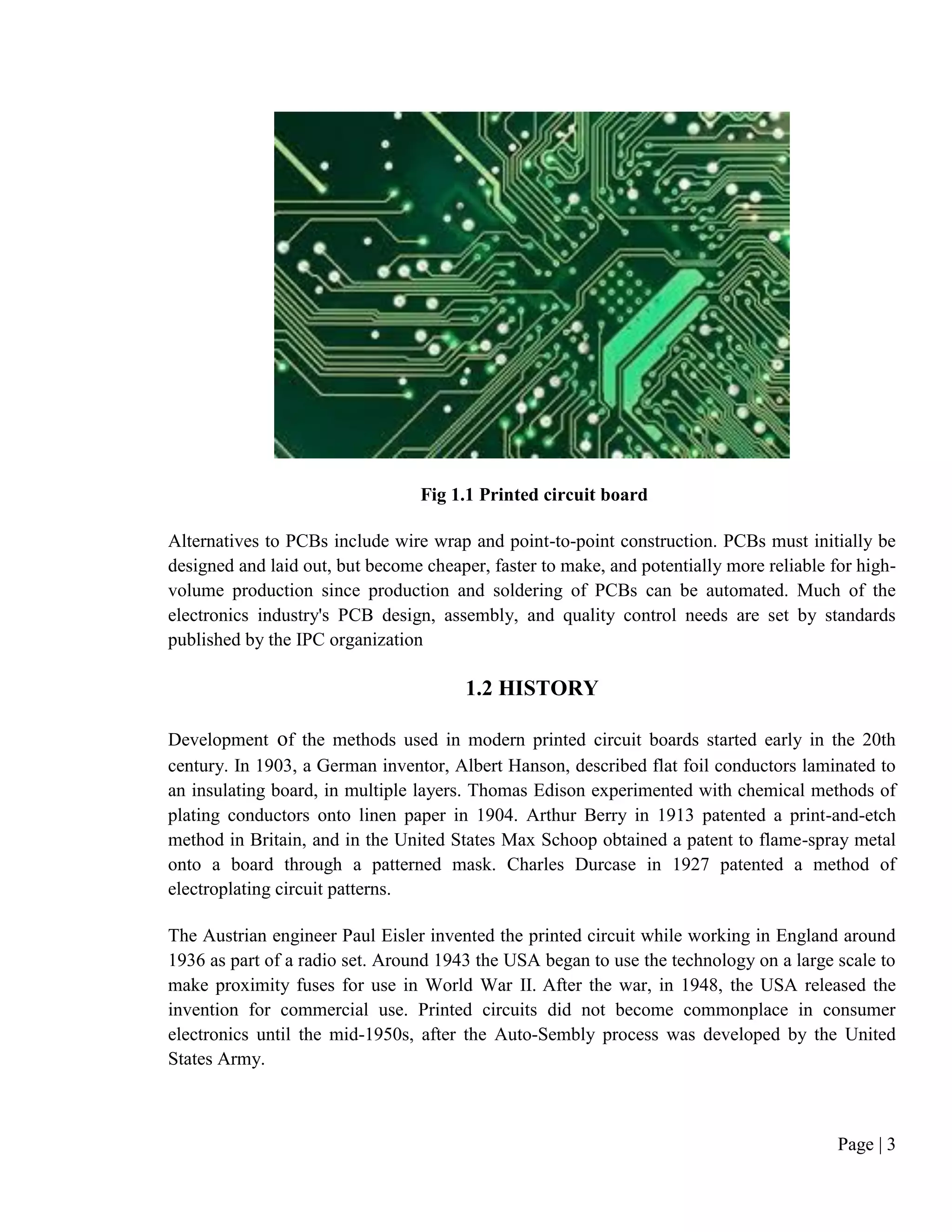

pick-and-place machines remove the parts from the tapes, tubes or trays and place them on the

PCB.

The boards are then conveyed into the reflow soldering oven. They first enter a pre-heat zone,

where the temperature of the board and all the components is gradually, uniformly raised. The

boards then enter a zone where the temperature is high enough to melt the solder particles in the

solder paste, bonding the component leads to the pads on the circuit board. The surface tension

of the molten solder helps keep the components in place, and if the solder pad geometries are

correctly designed, surface tension automatically aligns the components on their pads. There are

a number of techniques for reflowing solder. One is to use infrared lamps; this is called infrared

reflow. Another is to use a hot gas convection. Another technology which is becoming popular

again is special fluorocarbon liquids with high boiling points which use a method called vapor

phase reflow. Due to environmental concerns, this method was falling out of favor until lead-free

legislation was introduced which requires tighter controls on soldering. Currently, at the end of

2008, convection soldering is the most popular reflow technology using either standard air or

nitrogen gas. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages. With infrared reflow, the board

designer must lay the board out so that short components don't fall into the shadows of tall

components. Component location is less restricted if the designer knows that vapor phase reflow

or convection soldering will be used in production. Following reflow soldering, certain irregular

or heat-sensitive components may be installed and soldered by hand, or in large-scale

automation, by focused infrared beam (FIB) or localized convection equipment.

If the circuit board is double-sided then this printing, placement, reflow process may be repeated

using either solder paste or glue to hold the components in place. If a wave soldering process is

used, then the parts must be glued to the board prior to processing to prevent them from floating

off when the solder paste holding them in place is melted.

After soldering, the boards may be washed to remove flux residues and any stray solder balls that

could short out closely spaced component leads. Rosin flux is removed with fluorocarbon

solvents, high flash point hydrocarbon solvents, or low flash solvents e.g. limonene (derived

from orange peels) which require extra rinsing or drying cycles. Water-soluble fluxes are

removed with deionized water and detergent, followed by an air blast to quickly remove residual

water. However, most electronic assemblies are made using a "No-Clean" process where the flux

residues are designed to be left on the circuit board [benign]. This saves the cost of cleaning,

speeds up the manufacturing process, and reduces waste.

Certain manufacturing standards, such as those written by the IPC - Association Connecting

Electronics Industries require cleaning regardless of the solder flux type used to ensure a

thoroughly clean board. Even no-clean flux leaves a residue which, under IPC standards, must be

removed. Proper cleaning removes all traces of solder flux, as well as dirt and other

contaminants that may be invisible to the naked eye. However, while shops conforming to IPC

standard are expected to adhere to the Association's rules on board condition, not all

manufacturing facilities apply IPC standard, nor are they required to do so. Additionally, in some](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/projectreport-copy-150901073452-lva1-app6891/75/PCB-26-2048.jpg)