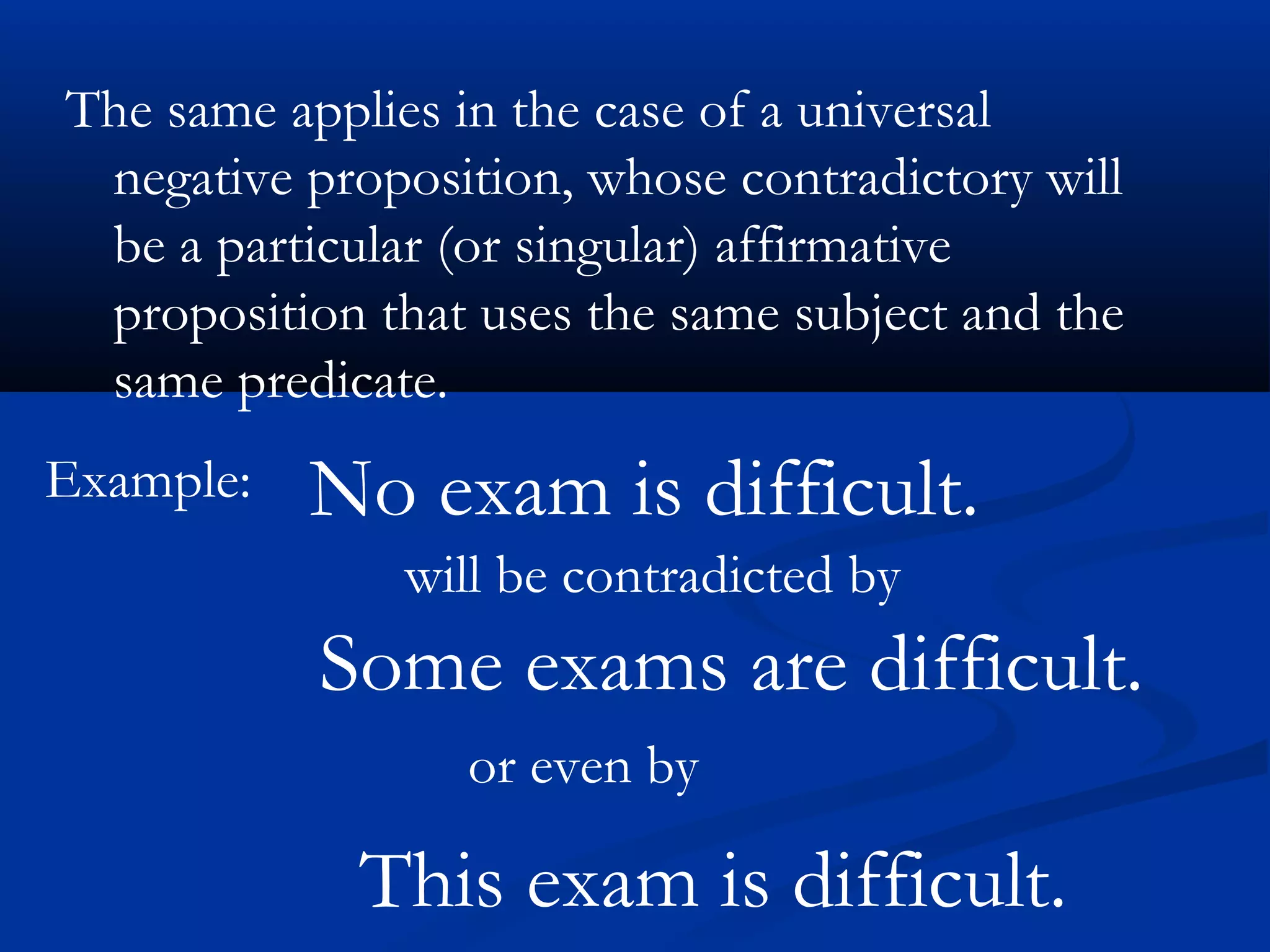

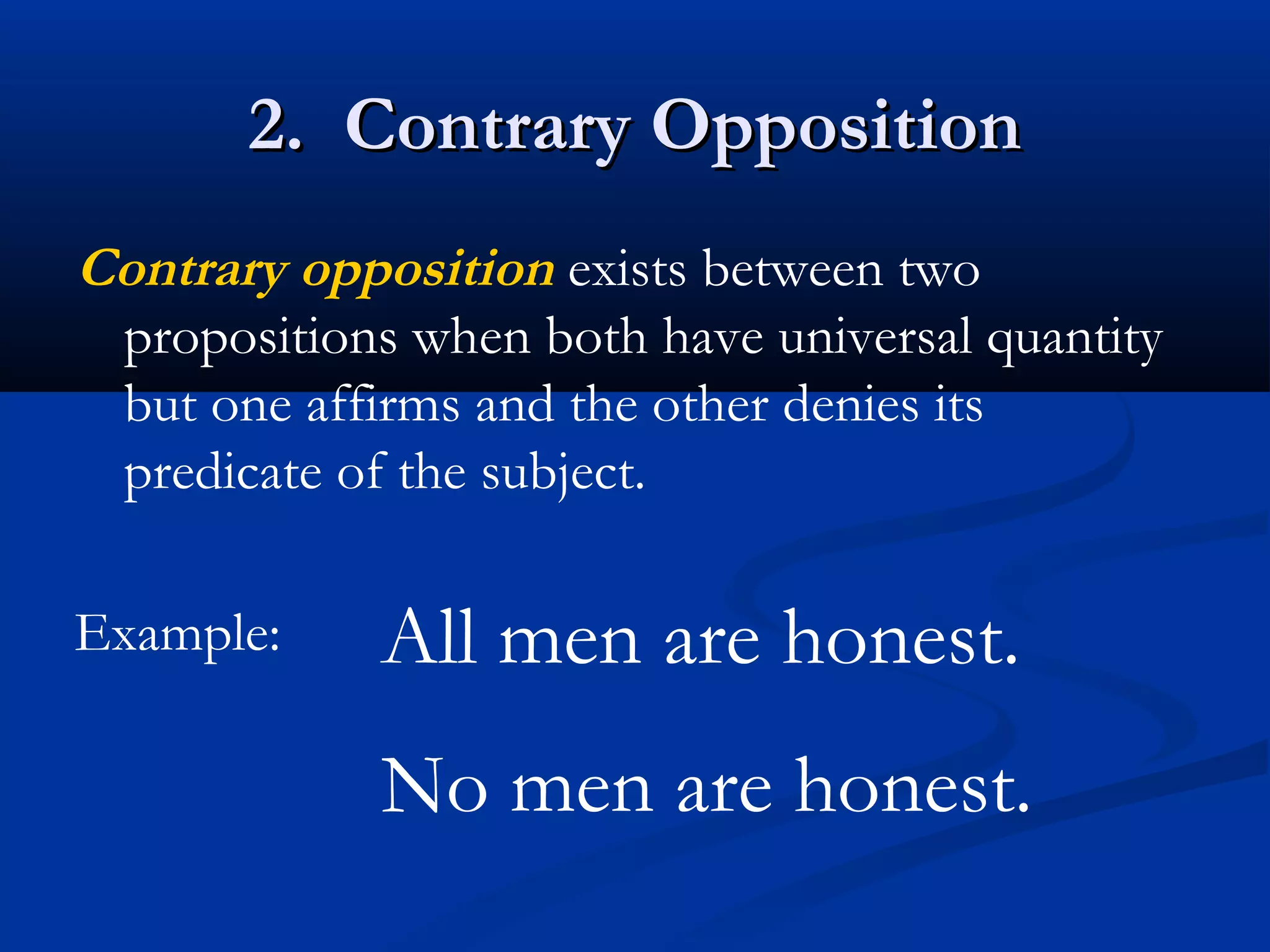

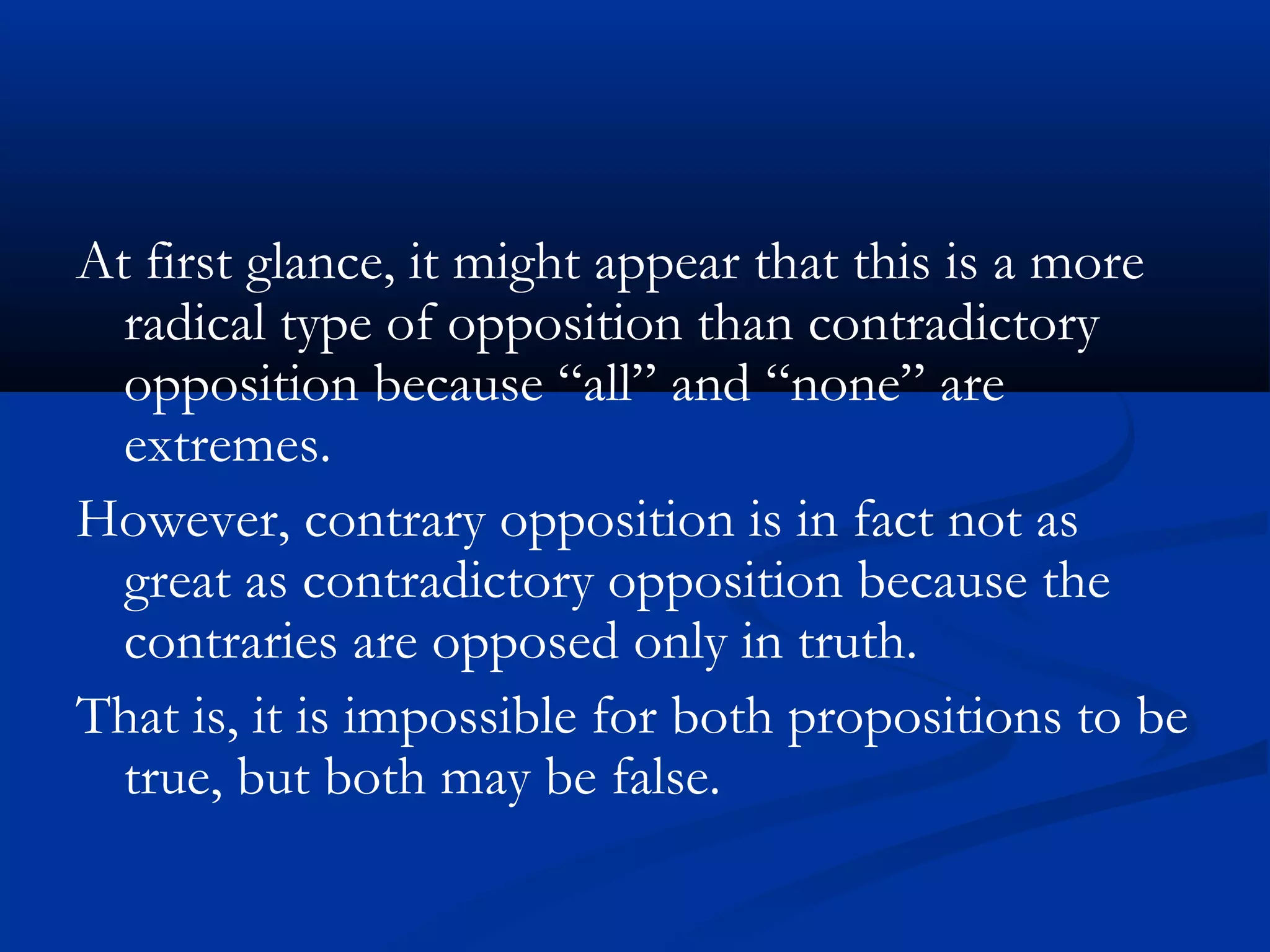

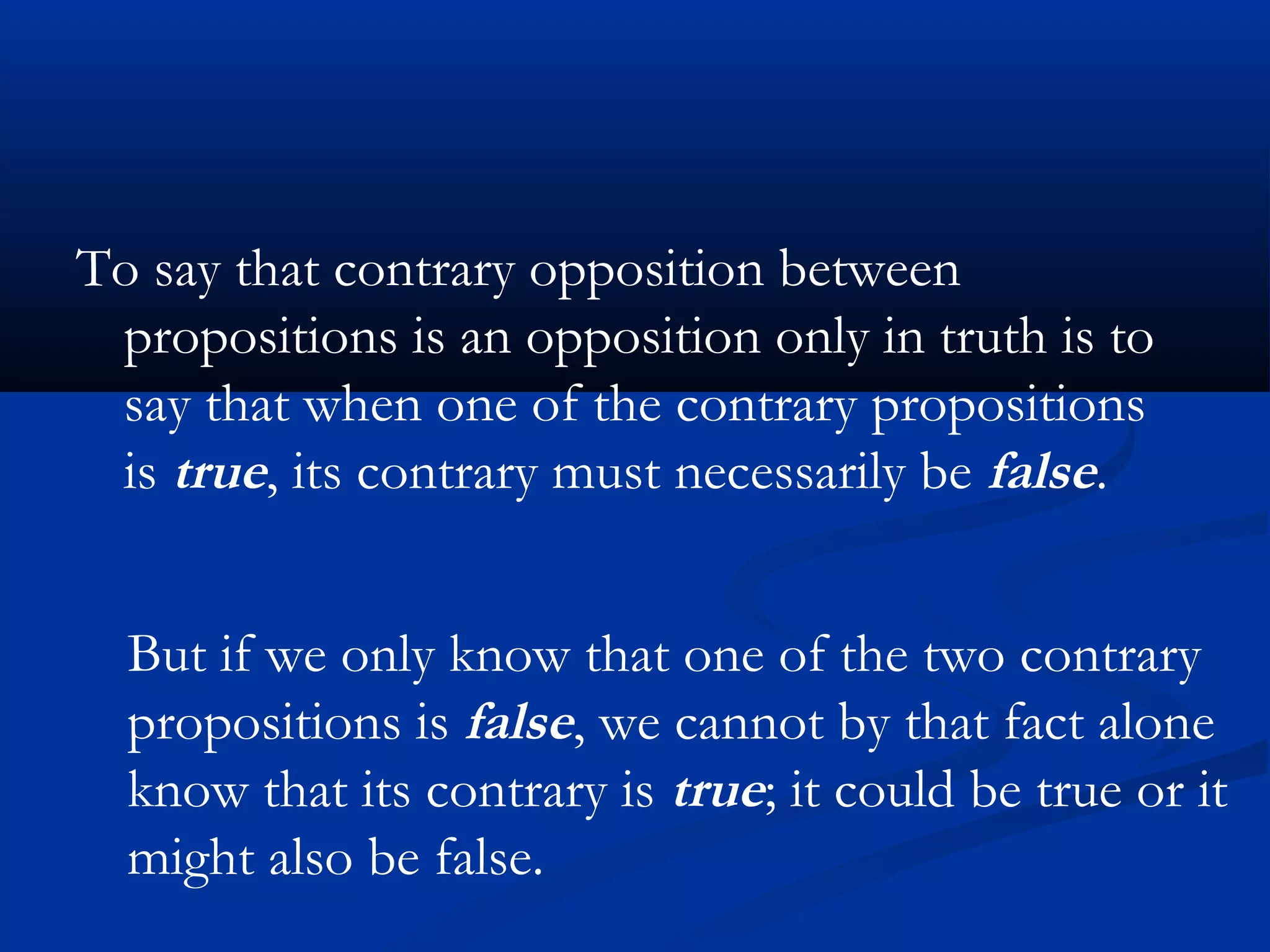

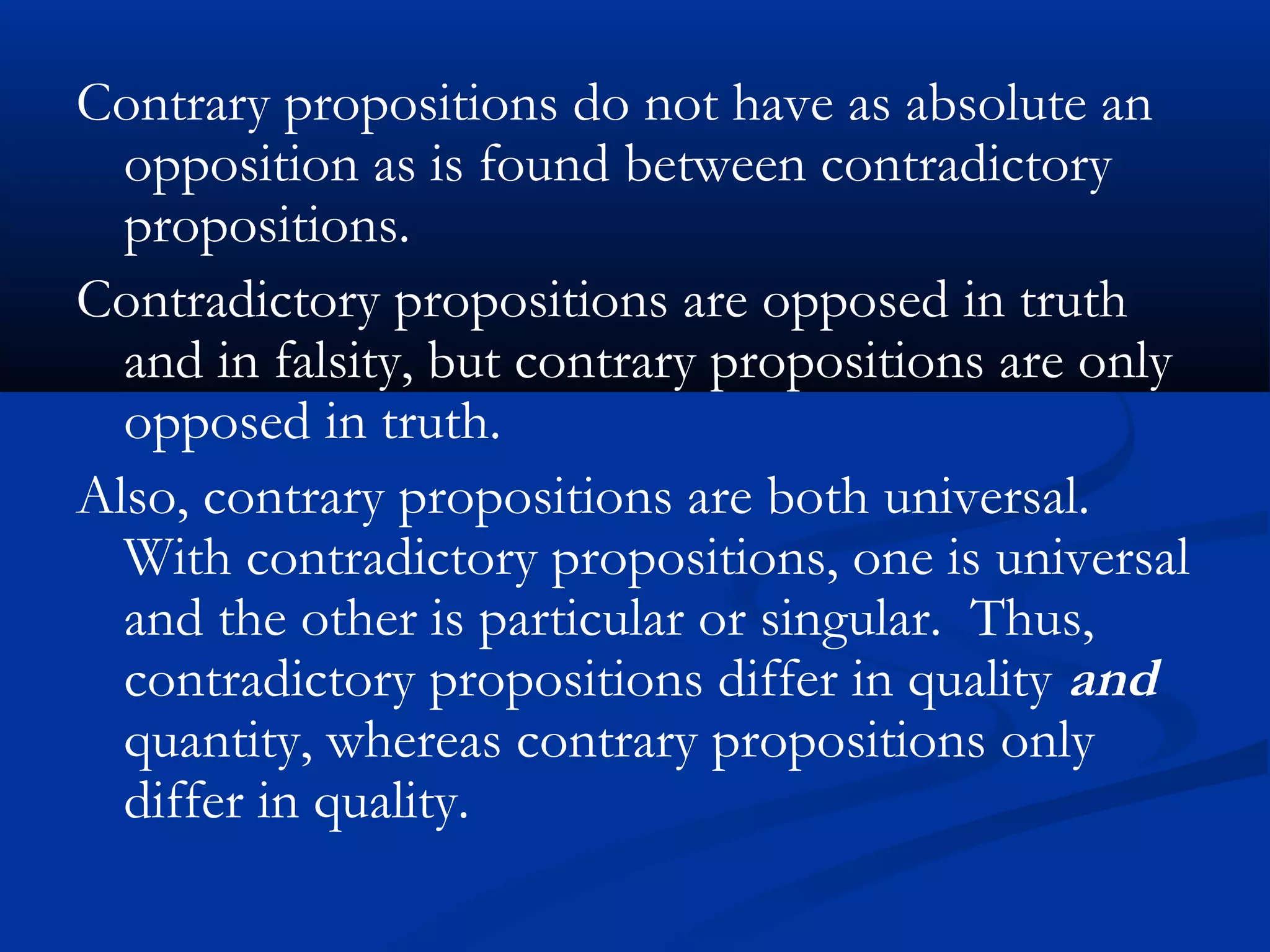

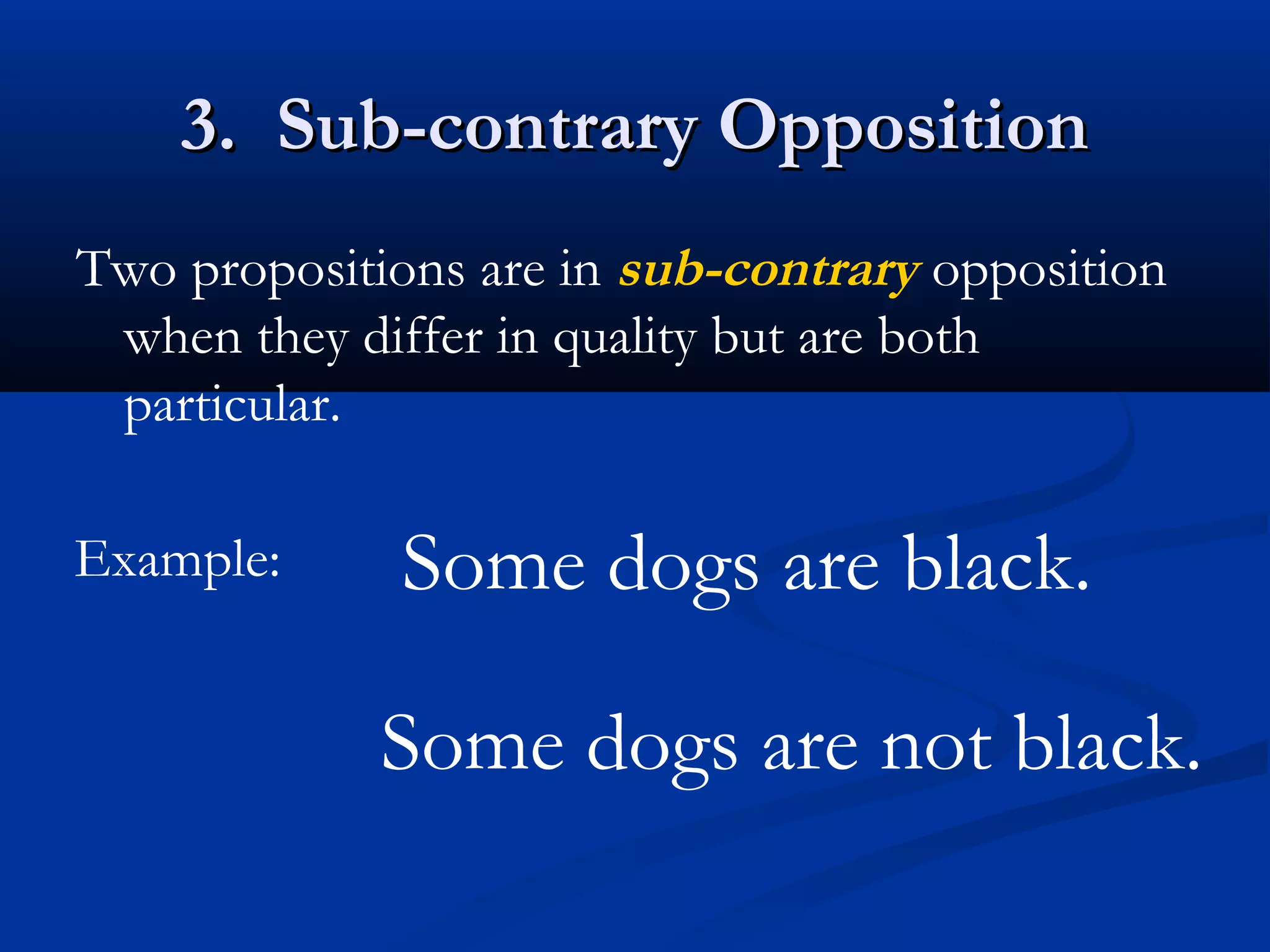

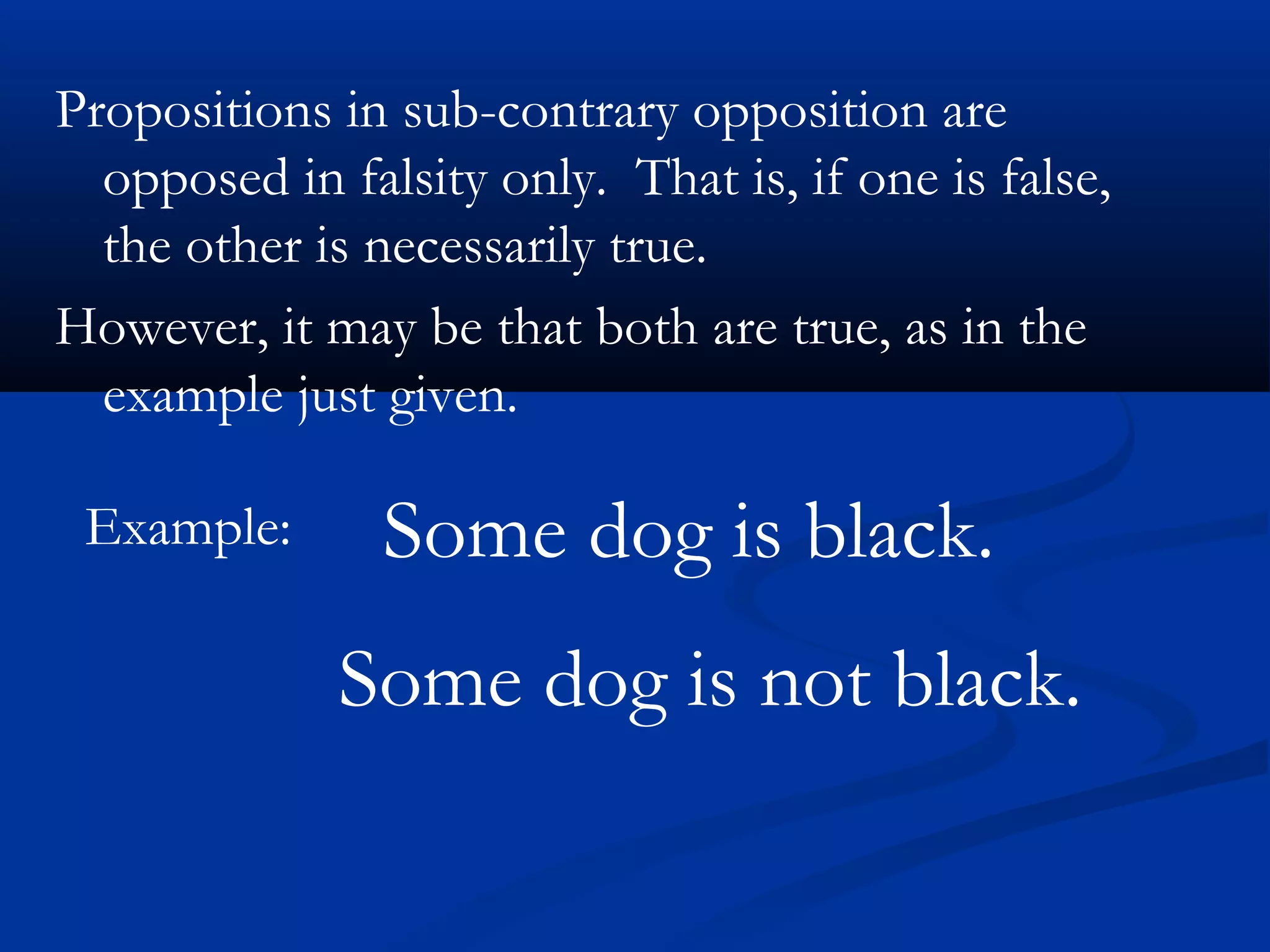

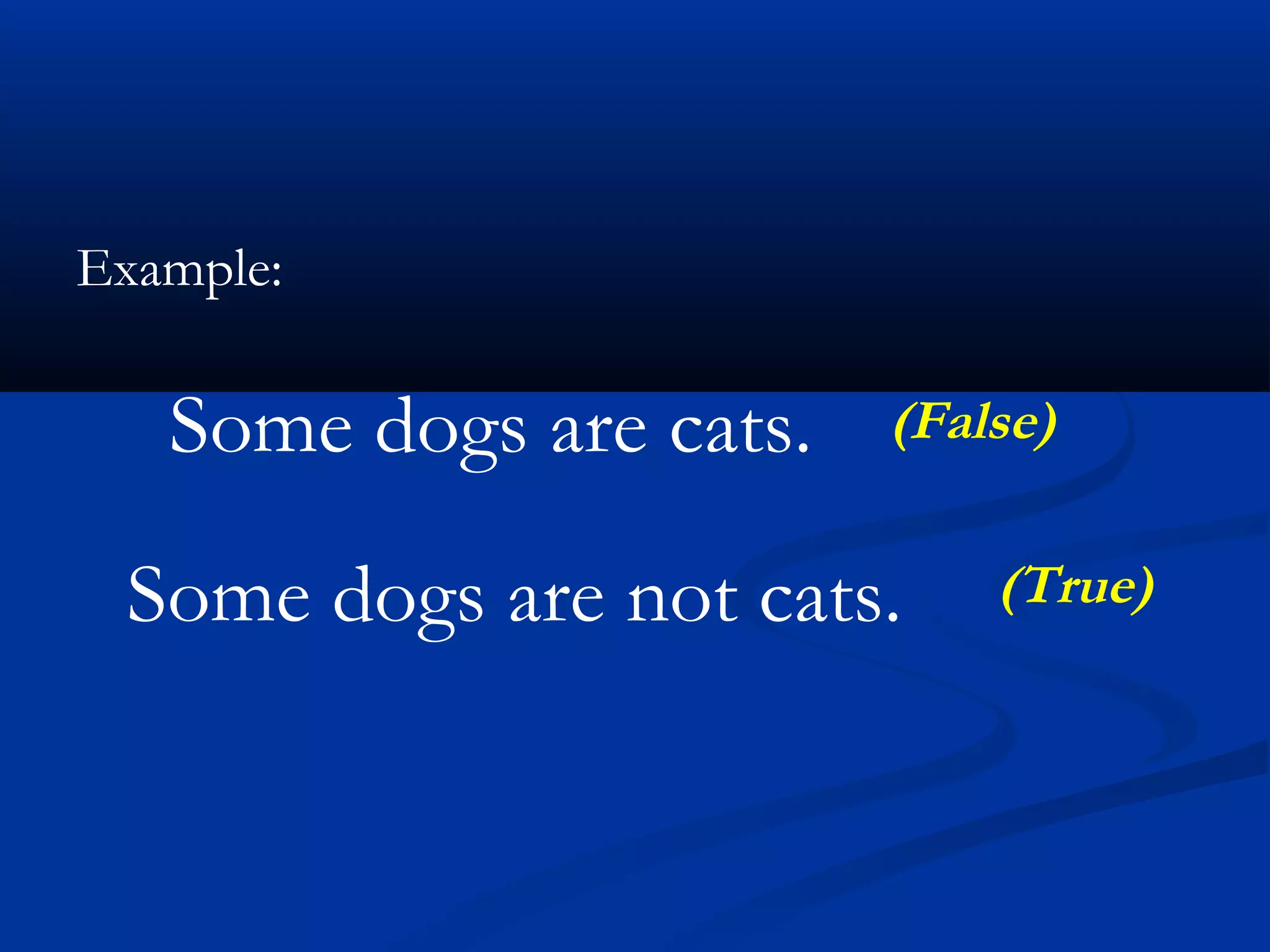

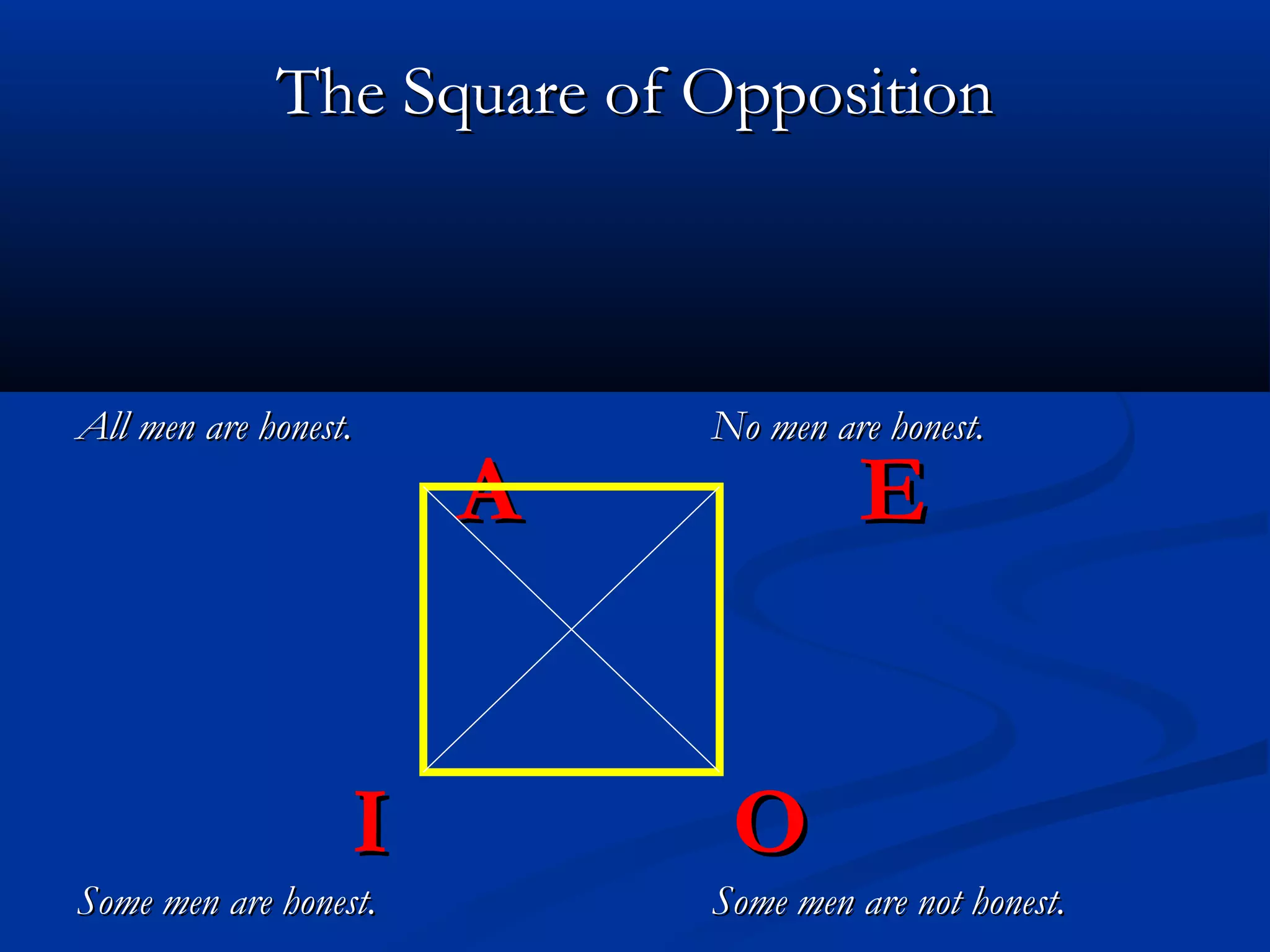

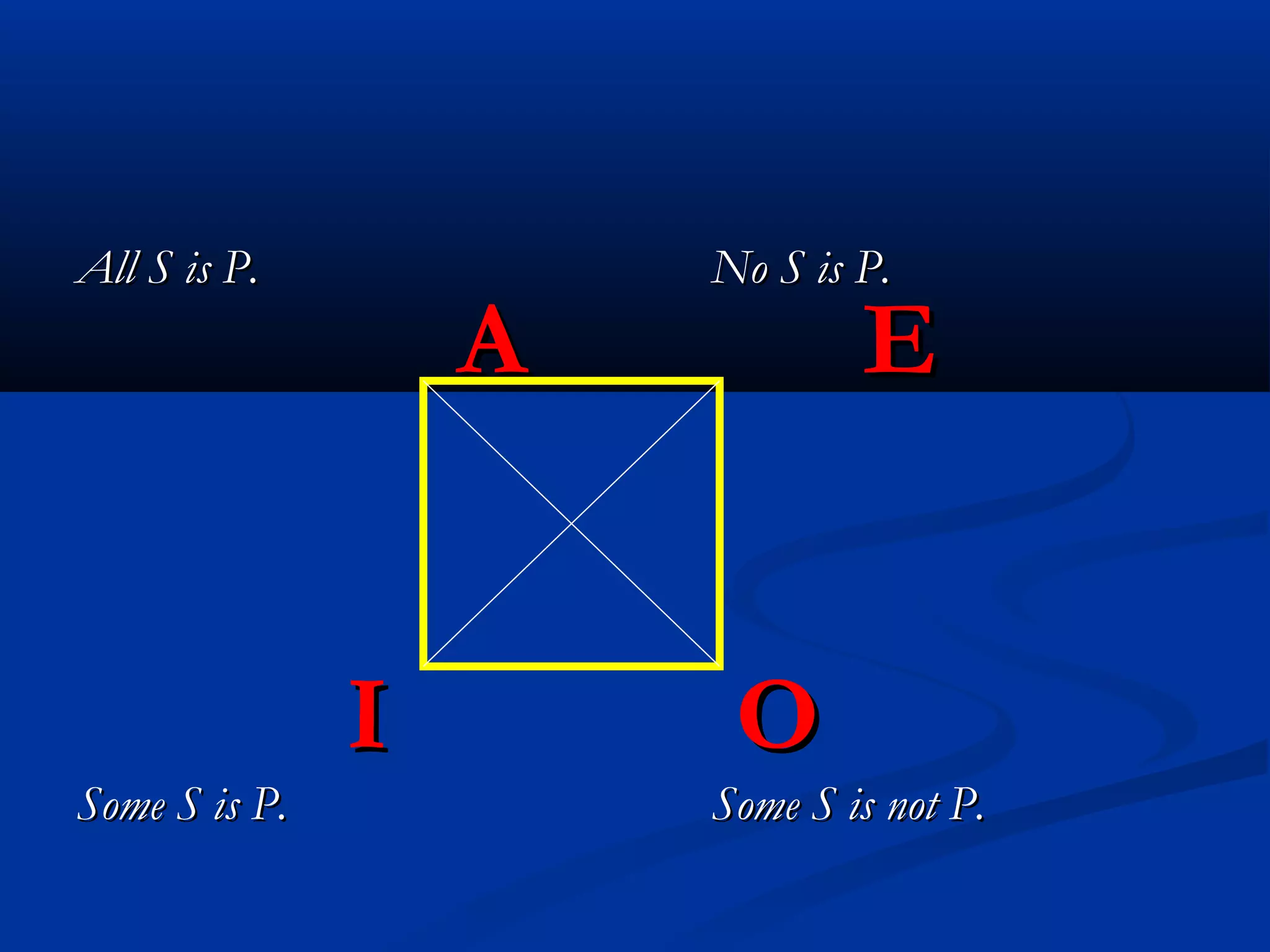

The document discusses the opposition and relation between propositions. It defines three types of opposition between propositions: contradictory, contrary, and sub-contrary. Contradictory propositions cannot both be true or false, contrary propositions cannot both be true, and sub-contrary propositions cannot both be false. It also discusses the relation of sub-alternation between propositions. The square of opposition is presented as a visual aid to understand these relationships between propositions.