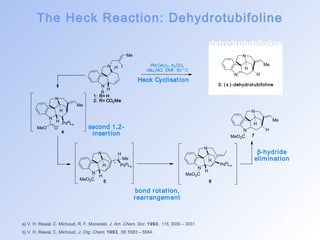

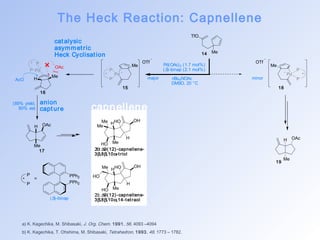

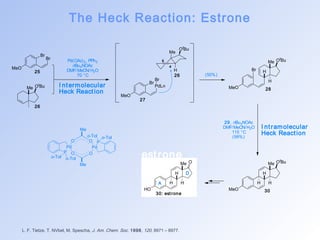

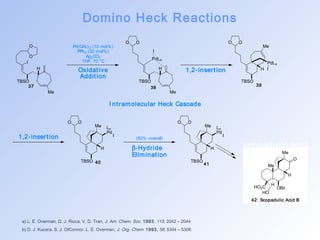

This document summarizes key aspects of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, with a focus on the Heck reaction and its mechanisms and applications. The Heck reaction involves the coupling of alkenyl or aryl halides with alkenes, catalyzed by palladium. The mechanism proceeds through oxidative addition, transmetalation, and reductive elimination steps. The document discusses factors that determine regioselectivity and provides examples of the Heck reaction in total syntheses of natural products like dehydrotubifoline, capnellene, and taxol. It also describes domino and intramolecular Heck reactions and summarizes the related Stille coupling reaction.

![Introduction

• Since Mizoroki[1] developed the first palladium catalysed reaction, research in this area has

developed exponentially, with each new issue of Angewandte Chemie or JACS highlighting the

latest techniques and processes.

• These reactions show a breadth of applications, not just in the type of transformation, but in the

target structure and scale of the process. Indeed, it is common to see the retrosynthesis of

industrial targets hinge upon a crucial palladium-mediated reaction.

Pd

1. T. Mizoroki, K. Mori, A. Ozaki, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1971, 44, 581

(There is still some debate as to which coupling was developed first; many claim that the Kumada coupling of sp2 grignard reagents with

aryl, vinyl or alkyl halides was the first. However, the intrinsic reactivity of grignard reagents with other common functionalities mean that

this coupling is seldom used.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-2-320.jpg)

![Why Palladium?

• Why is palladium such an adept catalyst centre? Why not sodium?

• The reason seems to be based around its electronegativity, which leads to relatively strong Pd-H

and Pd-C bonds, and also develops a polarised Pd-X bond.

• It allows easy access to the Pd (II) and Pd (0) oxidation states, essential for processes such as

oxidative addition, transmetalation and reductive elimination,

• Pd (I), Pd (III) and Pd (IV)[2] complexes are also known, though less thoroughly, with Pd (IV)

species essential in C-H activation mechanisms.

2. Pd (VI) complexes has also been proposed (W. Chen, S. Shimada, M. Tanaka, Science, 2002, 295, 308), but theoretical articles

counter-argue this (E. C. Sherer, C. R. Kinsinger, B. L. Kormos, J.D. Thompson, C. J. Cramer Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1953).

The debate is ongoing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-3-320.jpg)

![The Heck Reaction

• Broadly defined as the palladium-catalyzed coupling of alkenyl or aryl

(sp2) halides or triflates with alkenes to yield products which formally

result from the substitution of a hydrogen atom in the alkene coupling

partner.

• First discovered by Mizoroki, though developed and applied more

thoroughly by Richard F. Heck in the early 1970s.[3]

• Generally thought of as the original palladium catalysed cross-coupling,

and probably the best evolved, including a multitude of

asymmetric varients.[4]

H

R1

R2

R3

cat. [Pd0Ln]

R4 X R4

R1

R2

R3

base

R4 = aryl, benzyl, vinyl

X = Cl, Br, I, OTf

3. R. F. Heck, J. P. Nolley, Jr., J. O rg . Che m . 1972, 3 7 , 2320

4. Review on asymmetric Heck reactions: A. B. Dounay, L. E. Overman, Che m . Re v. 2003, 1 0 3 , 2945 – 2963](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-4-320.jpg)

![The Heck Reaction: Taxol

OTf

O

O

O

Me

OTBS

Me

H

BnO

O

[Pd(PPh3)4] (110 mol%)

I nt ramolecular

Heck React ion

O

O

O

M. S. (4 A)

K2CO3, MeCN, 90 °C

(49%)

Me

OTBS

Me

H

BnO

O

22

AcO

O

HO

BzO

Me

OH

Me

H

AcO

O

O

O

taxol

BzHN

Ph

OH

23

24: t axol

a) S. J. Danishefsky, J. J. Masters, W. B. Young, J. T. Link, L. B. Snyder, T. V. Magee, D. K. Jung, R. C. A. Isaacs, W. G. Bornmann, C. A.

Alaimo, C. A. Coburn, M. J. Di Grandi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 2843 – 2859

b) J. J. Masters, J. T. Link, L. B. Snyder, W. B. Young, S. J. Danishefsky, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1723 – 1726.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-10-320.jpg)

![Domino Heck Reactions

Me

EtO2C

EtO2C

I

Me

EtO2C

EtO2C

I

Y. Zhang, G.Wu, G. Angel, E. Negishi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8590 – 8592.

Me

EtO2C

EtO2C

[Pd(PPh3)4] (3 mol%)

Et3N (2 eq.)

MeCN, 85 °C

(76%)

I nt ramolecular

Domino Heck

32 Cyclisat ion 33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-12-320.jpg)

![The Stille Coupling

• Originally discovered by Kosugi et al[5] in the late 1970s, the Stille Coupling was later developed

as a tool for organic transformations by the late Professor J. K. Stille.[6]

• Milder than the older Heck reaction, and more functional-group tolerant, the Stille coupling

remains popular in organic synthesis.

R1 R2 X cat. [Pd0Ln]

SnR3 R1 R3

base

R1 = alkyl, alkynyl, aryl, vinyl

R2 = acyl, alkynyl, allyl, aryl, benzyl, vinyl

X = Br, Cl, I, OAc, OP(=O)(OR)2, OTf

5. Original Report; a) M. Kosugi, K. Sasazawa, Y. Shimizu, T. Migita, Chem. Lett. 1977, 301 – 302; b) M. Kosugi, K. Sasazawa, T. Migita,

Chem. Lett. 1977, 1423 – 1424.

• 6. A a) close D. Milstein, relative J. K. Stille, of the J. Am. Stille Chem. coupling Soc. 1978, is 100the , 3636 Hiyama; – 3638; b) this D. Milstein, involves J. K. the Stille, palladium J. Am. Chem. catalysed Soc. 1979, 101reaction

, 4992 –

4998; c) For a review of Stille Reactions, see; V. Farina, V. Krishnamurthy,W. J. Scott, Org. React. 1997, 50, 1 – 652

of a organosilicon with organic halides/triflates et c., but requires activation with fluoride (TBAF)

or hydroxide.[7]

7. T. Hiyama, Y. Hatanaka, Pure Appl. Chem. 1994, 66, 1471

8. T. R. Kelly, Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 161

• It is possible to couple bis-aryl halides using R3Sn-SnR3, in a varient known as a Stille-Kelly

reaction, but the toxicity of these species is a somewhat limiting factor.[8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-14-320.jpg)

![The Stille Coupling: Rapamycin

O

Me

O

O N

Me

I

I

O

Me

O

H

O

O

H

OH

Bu3Snn

Me

O

Me

O

Me

72 74

O

"St it ching Cyclisat ion"

a) K. C. Nicolaou, T. K. Chakraborty, A. D. Piscopio, N. Minowa, P. Bertinato, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 4419 – 4420; K. C. Nicolaou, A. D.

Piscopio, P. Bertinato, T. K. Chakraborty, , N. Minowa, K. Koide, Chem. Eur. J. 1995, 1, 318 –333.

b) A. B. Smith III, S. M. Condon, J. A. McCauley, J. L. Leazer, Jr.,J. W. Leahy, R. E. Maleczka, Jr., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5407 – 5408.

Me

Me

OH

OMe Me

Me

H OH

OMe

OMe

SnnBu3

[PdCl2(MeCN)2]

(20 mol%)

iPr2NEt, DMF,

THF, 25°C

I ntermolecular

St ille Coupling

O

O

O N

I

O

Me

O

O

H

OH

H

Me

Me

OH

OMe Me

Me

H OH

OMe

OMe

SnnBu3

I nt ramolecular

St ille Coupling

O

O

O N

Me

O

Me

O

O

H

OH

H

Me

Me

OH

OMe Me

Me

H OH

OMe

OMe

O

O

O N

Me

O

Me

O

O

H

OTIPS

H

Me

Me

OTBS

OMe Me

Me

H TESO

Me

OMe

OMe

SnnBu3

I

1. [PdCl2(MeCN)2] (20 mol%)

iPr2NEt, DMF, THF, 25°C (74%)

2. Deprotection (61%)

I nt ramolecular

St ille Coupling

27%

Overall

rapamycin

75 76: Rapamycin](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-16-320.jpg)

![The Stille Coupling: Dynamycin

TeocN

I

I

O

OH

OH

Me

H

OTBS

Me3Sn SnMe3

[Pd(PPh3)4] (5 mol%)

DMF, 75 °C

81%

Tandem

I nt ermolecular

St ille Coupling

TeocN

O

OH

OH

Me

H

OTBS

dynemicin

HN

O

CO2H

OMe

Me

H

OH

O

O

OH

OH

77 81: (± ) Dynamycin

79

Teoc = 2-(trimethylsilyl)ethoxycarbonyl

a) M. D. Shair, T.-Y. Yoon, K. K. Mosny, T. C. Chou, S. J. Danishefsky, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 9509 – 9525;

b) M. D. Shair, T.-Y. Yoon, S. J. Danishefsky, Angew. Chem. 1995, 107, 1883 – 1885; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1721 – 1723;

c) M. D. Shair, T. Yoon, S. J. Danishefsky, J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 3755 – 3757.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-17-320.jpg)

![The Stille Coupling: Sanglifehrin

Me

O O

NH

N

O

O

NH

SnnBu3

Me

HN

Me

OH

O Me

O

Me

O

O O

NH

O

HN

O O

NH

O

HN

sanglifehrin

O

86 87

O

a) K. C. Nicolaou, J. Xu, F. Murphy, S. Barluenga, O. Baudoin, H.-X.Wei, D. L. F. Gray, T. Ohshima, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2447 –

2451;

b) K. C. Nicolaou, F. Murphy, S. Barluenga, T. Ohshima, H. Wei, J. Xu, D. L. F. Gray, O. Baudoin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 3830 – 3838.

I

I

[Pd2(dba)3]•CHCl3

AsPh3, iPr2NEt

DMF, 25 °C, 62%

Chemoselect ive

I nt ramolecular

St ille macrocyclisat ion

N

O

NH

OH

O

Me

Me

O

Me

O Me

Me

I

1. [Pd2(dba)3] •CHCl3

AsPh3, iPr2NEt

DMF, 40°C, 45%

2. aq. H2SO4

THF/H2O

(33%)

I nt ermolecular

St ille Coupling

N

O

NH

OH

O

Me

Me

O

Me

O Me

Me Me

NH

O

Me

OH

Me

Me

Me

Me

Me

NH

O

Me

OH

Me

Me

Me

Me 88

87: sanglifehrin A

SnnBu3

23

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-18-320.jpg)

![The Stille Coupling: Manzamine A

CO2Me

NBoc

OTBDPS

O

N

Br

TBDPSO

SnnBu3

[Pd(PPh3)4)] (4 mol%)

toluene, 120 °C

I nt ermolecular

St ille Coupling

109

CO2Me

NBoc

OTBDPS

O

N

TBDPSO

N

O

OTBDPS

TBDPSO

N

H Boc E

110

N

O

H

H

OTBDPS

OTBDPS

CO2Me

NBoc

111

endo -int ramolecular

Diels-Alder React ion

(68% Overall)

manzamine

N NH

N

H

A B

C

D

N

H

H

OH

112: Manzamine A

a) S. F. Martin, J. M. Humphrey, A. Ali, M. C. Hillier, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 866 – 867;

b) J. M. Humphrey, Y. Liao, A. Ali, T. Rein, Y.-L. Wong, H.-J. Chen, A. K. Courtney, S. F. Martin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8584 – 8592.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-19-320.jpg)

![The Carbonylative Stille Coupling:

Jatrophone

O Me

O

Me

82 83

j at rophone

O Me

O

Me O

Me

Me

Me

Me O

Me

Me

Me

Me

A. C. Gyorkos, J. K. Stille, L. S. Hegedus, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8465 – 8472.

O Me

Me

Me

Me

[PdCl2(MeCN)2]

LiCl, CO (50 psi)

DMF, 25 °C

I ntermolecular

Carbonylat ive

SnnBu3 St ille Coupling

OTf

SnnBu3

PdLn

Cl

O Me

O

Me

Me

Me

SnnBu3

53% Overall

Cl

PdLn

O

85: (± )-2-epi-jatrophone 84

Carbonyl

I nsert ion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-20-320.jpg)

![The Suzuki Coupling

• The Suzuki reaction was formally developed by Suzuki Group in

1979[9], although the inspiration for this work can be traced back

to publications by Heck[10] and Negishi,[11] and their earlier

presentation of these papers at conferences.

• The popularity of this reaction can be partially attributed to the

ease of preparation of the organoboron reagents required, their

general stability, and the lack of toxic by-products.

• Progress in the last quarter-century has shown that the Suzuki

reaction is incredibly powerful, with examples of C(sp2)–C(sp3)

and even C(sp3)–C(sp3) now well documented.[12]

R1 R2 X cat. [Pd0Ln]

BY2 R1 R2

base

R1 = alkyl, alkynyl, aryl, vinyl

R2 = alkyl, alkynyl, aryl, benzyl, vinyl

X = Br, Cl, I, OAc, OP(=O)(OR)2, OTf

9. Original Report; a) N. Miyaura, K. Yamada, A. Suzuki, Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 3437 – 3440; b) N. Miyaura, A. Suzuki, J. Chem.

Soc. Chem. Commun. 1979, 866 – 867

10. a) R. F. Heck in Proceedings of the Robert A. Welch Foundation Conferences on Chemical Research XVII. Organic-Inorganic Reagents

in Synthetic Chemistry (Ed.W. O. Milligan), 1974, p. 53–98; b) H. A. Dieck, R. F. Heck, J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 1083 – 1090.

11. E. Negishi in Aspects of Mechanism and Organometallic Chemistry (Ed.: J. H. Brewster), Plenum, New York, 1978, p. 285.

12. a) T. Ishiyama, S. Abe, N. Miyaura, A. Suzuki, Chem. Lett. 1992, 691 – 694. b) J. Zhou, G.C. Fu, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1340 –

1341, and references therein. c) A. C. Frisch, M. Beller, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 674 – 688. d) For a relatively recent review,

see N. Miyaura, A. Suzuki, Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 2457.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-21-320.jpg)

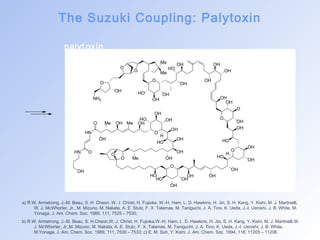

![The Suzuki Coupling: Palytoxin

O

O

OTBS

NHTeoc

Me

O Me

O

TBSO OTBS

TBSO OTBS

OTBS

B

OTBS

TBSO

TBSO

OTBS

HO

OH

O

OAc I

OTBS

TBSO OTBS

OTBS

OTBS

O OTBS

CO2Me

TBSO

TBSO

H

OTBS

I ntermolecular

Suzuki Coupling

[Pd(PPh3)4] (40 mol%)

TlOH, THF/H2O, 25 °C

(70%)

O

O

OTBS

TeocHN

O

Me

Me

O

TBSO

TBSO

OTBS

TBSO OTBS OTBS

OTBS

TBSO OTBS

O

OAc

OTBS

OTBS

OTBS

OTBS

TBSO

O

MeO2C

TBSO H

OTBS

OTBS OTBS

a) R.W. Armstrong, J.-M. Beau, S. H. Cheon, W. J. Christ, H. Fujioka, W.-H. Ham, L. D. Hawkins, H. Jin, S. H. Kang, Y. Kishi, M. J. Martinelli,

W. J. McWhorter, Jr., M. Mizuno, M. Nakata, A. E. Stutz, F. X. Talamas, M. Taniguchi, J. A. Tino, K. Ueda, J.-I. Uenishi, J. B. White, M.

Yonaga, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7525 – 7530;

b) R.W. Armstrong, J.-M. Beau, S. H.Cheon,W. J. Christ, H. Fujioka,W.-H. Ham, L. D. Hawkins, H. Jin, S. H. Kang, Y. Kishi, M. J. Martinelli,W.

J. McWhorter, Jr.,M. Mizuno, M. Nakata, A. E. Stutz, F. X. Talamas, M. Taniguchi, J. A. Tino, K. Ueda, J.-I. Uenishi, J. B. White,

M.Yonaga, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 7530 – 7533;

c) E. M. Suh, Y. Kishi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 11205 – 11206.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-23-320.jpg)

![The Suzuki Coupling: FR182887

MeO

O

Me

Br

OTBS

Me Me Br

126 127

O

OTBS

HO

H Me

HO

[PdCl2(dppf))] (10 mol%)

Cs2CO3, DMF/H2O, 100 °C

O Me

B

HO

H Me

HO

HO

H Me

O

O

130 129

a) D. A. Evans, J. T. Starr, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13531 –13540

b) D. A. Evans, J. T. Starr, Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 1865 – 1868; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1787 – 1790.

TBDPSO

B

OTBS

Me

OTBS

HO

OH

[Pd(PPh3)4)] (5 mol%)

Tl2CO3, THF/H2O, 23 °C

(84%)

I ntermolecular

Suzuki Coupling

TBDPSO

OTBS

Me

OTBS

MeO

Me

Me Me Br

O

OH

Br

H H

H

CO2Et

H

Me

Me

H

B

O

B

O

Me

Me

(71%)

O

OH

Me

H H

H

CO2Et

H

Me

Me

H O

OH

Me

H H

H

H

Me

Me

H

fr182887

131 132: FR182887

128

I ntermolecular

Suzuki Coupling](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-25-320.jpg)

![The Suzuki Coupling: Dragmacidin Me

TBSO

HO

Br

O N SEM

[Pd(PPh3)4] (10 mol%)

toluene/MeOH/H2O, 23 °C

I ntermolecular

Heck React ion

Me

TBSO

HO

PdOAc

O N SEM

162 164

TBSO

HO

O

(74%)

N SEM

H

TBSO

MeO

H

O

O N SEM

B O

166 165

[Pd(PPh3)4] (10 mol%)

161, toluene/MeOH/H2O

NaCO3, 50 °C, 77%

I ntermolecular

Suzuki React ion

TBSO

MeO

H

O N SEM

NTs

Br

N

N

OMe

167

dragmacidin

HO

Me NH

H

O NH

N

HO N

159 160

N

Br OMe

a) N. K. Garg, D. D. Capsi, B. M. Stoltz, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9552 – 9553.

b) For a failed alternative route without Pd Catalysis: N. K. Garg, R. Sarpong, B. M. Stoltz, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13179 – 13184.

Br

NH

O

N

N

H2N

168: dragmacidin

Ts

N

B

Br

OH

N I

Br OMe

[Pd(PPh3)4] (10 mol%)

toluene/MeOH/H2O, 23 °C

(71%)

I ntermolecular

Suzuki

Coupling

NTs

Br

N

161](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-26-320.jpg)

![The Suzuki-Miyaura B-Alkyl Coupling: CP-236,114

O

TBS I

169 170

173 171 CP-263,114

13) a) N. Miyaura, T. Ishiyama, M. Ishikawa, A. Suzuki, Tetrahedron Lett. 1986, 27, 6369 – 6372; b) not to be confused with the Miyaura

boration, in which an aryl halide is converted to an aryl boronate via palladium catalysis and a diboron reagent. However, this is a useful

preparation of the organoboron reagents required for the Suzuki reaction. See: T. Ishiyama, M. Murata, N. Miyuara. J. Org. Chem.

1995, 60, 7508.

14) Review of the development, mechanistic background, and applications of the B-alkyl Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction, see S. R.

Chemler, D. Trauner, S. J. Danishefsky, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 4544 – 4568.

15) Q. Tan, S. J. Danishefsky, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 4509 – 4511.

O

TBSO

H

O

TBS

O

H

OTBS

O

TBS

OTBS

H

OTBS

I

O

TBS

OTBS

H

OTBS

OBn

6

O

O

O

O O

O

CO2H

H

Me

O

H

Me

[Pd(OAc)2(PPh3)2]

Et3N, THF, 65 °C

(92%)

I nt ermolecular

Heck React ion

B{ (CH2)6OBn} 3

[PdCl2(dppf)]

CsCO3, AsPh3, H2O, 25 °C

(70%)

Suzuki-Miyaura

B-Alkyl React ion

174: CP-263,114

• An important trend in Suzuki

chemistry is the development of a

C(sp3)–C(sp2) methodology, which

has become known as the Suzuki-

Miyaura B-Alkyl varient.[13-15]

• Often used as an alternative to

RCM, leaving a single isolated

double bond, rather than the

conjugated systems produced by a

regular Suzuki coupling.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-27-320.jpg)

![The Suzuki Coupling: Phomactin A

O

OTMS

O

H

Me

Me

OTES

Me

I

9-BBN

THF, 40 °C

phomact in

O

a) P. J. Mohr, R. L. Halcomb, J. Am. Chem. So c. 2003, 125, 1712 – 1713

b) N. C. Callan, R. L. Halcomb, Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2687 – 2690.

O

Me OTMS

O

H

Me

OTES

Me

I

B

O

O

Me H

OTMS

OTES

Me

Me

Me

O

Me H

OH

OH

Me

Me

Me

TBAF

(78%)

Suzuki-Miyaura

B-Alkyl

Macrocyclisat ion

[PdCl2(dppf)] (100 mol%)

AsPh3(200 mol%), Tl2CO3

THF/DMF/H2O, 25 °C

(37%)

200: phomact in A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-28-320.jpg)

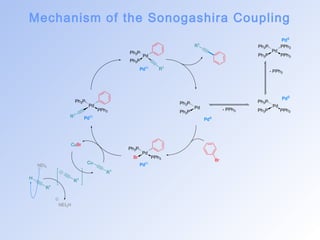

![The Sonogashira Coupling

• The coupling of terminal alkynes with vinyl or aryl halides via palladium catalysis was first

reported independently and simultaneously by the groups of Cassar[16] and Heck[17] in 1975.

• A few months later, Sonogashira and co-workers demonstrated that, in many cases, this cross-coupling

reaction could be accelerated by the addition of cocatalytic CuI salts to the reaction

mixture.[18,19]

• This protocol, which has become known as the Sonogashira reaction, can be viewed as both an

alkyne version of the Heck reaction and an application of palladium catalysis to the venerable

Stephens–Castro reaction (the coupling of vinyl or aryl halides with stoichiometric amounts of

copper(I) acetylides).[20]

• Interestingly, the utility of the “copperfree” Sonogashira protocol (i.e. the original Cassar–Heck

version of this reaction) has subsequently been “rediscovered” independently by a number of

other researchers in recent years.[21]

R2 X

cat. [Pd0Ln]

R1 H R2 R2

16. L. Cassar, J. Organomet. Chem. 1975, 93, 253 – 259.

17. H. A. Dieck, F. R. Heck, J. Organomet. Chem. 1975, 93, 259 – 263.

18. K. Sonogashira, Y. Tohda, N. Hagihara, Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 4467 – 4470.

19. For a brief historical overview of the development of the Sonogashira reaction, see: K. Sonogashira, J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 653,

46 – 49.

20. R. D. Stephens, C. E. Castro, J. Org. Chem. 1963, 28, 3313 – 3315.

21. a) M. Alami, F. Ferri, G. Linstrumelle, Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 6403 – 6406; b) J.-P. Genet, E. Blart, M. Savignac, Synlett 1992, 715

– 717; c) C. Xu, E. Negishi, Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 431 – 434;

base

R1 = alkyl, aryl, vinyl

R2 = alkyl, benzyl, vinyl

X = Br, Cl, I, OTf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-30-320.jpg)

![The Sonogashira Coupling: Eicosanoid 212

Br Me

OTBS

TMS

[Pd(PPh3)4] (4 mol%)

CuI (16 mol%)

nPrNH2, C6H6, 25 °C

Sonogashira

Coupling

K. C. Nicolaou, S. E. Webber, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 5734 – 5736

R

Me

OTBS

AgNO3,

KCN

208: R = TMS

209: R = H

210, [Pd(PPh3)4] (4 mol%)

CuI (16 mol%)

nPrNH2, C6H6, 25 °C

76% Overall from 208

Br

CO2Me

OTBS

Me

OTBS

CO2Me

OTBS

Me

OH

CO2H

OH

Sonogashira

Coupling

206

207

210

212 211](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-32-320.jpg)

![The Sonogashira Coupling: Disorazole C1

PMBO

OH

PMBO

OH

218

[Pd(PPh3)2Cl2] (4 mol%)

CuI (30 mol%), Et3N

MeCN, -20 °C, 94%

217 219

O

O OMe

N

N

O

Me Me

P. Wipf, T. H. Graham, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15346 –15347.

Me

Me

Me

Me

Me

Me

N

CO2Me

MeO O

Sonogashira

Coupling

220, DCC, DMAP

80%

PMBO

Me

O

Me

Me

OMe

N

CO2Me

N

O

MeO O

O

I

218

[Pd(PPh3)2Cl2] (5 mol%)

CuI (20 mol%), Et3N

MeCN, -20 °C, 94%

Sonogashira

Coupling

PMBO

Me

O

Me

Me

O OMe

N

Me Me

CO2Me

N

O

MeO O

OH

Me

OPMB

Me

OH

Me

Me

MeO O

O

OH

Me

O

disorazole

N

O

RO

O

I

OMe

218: R = Me

220: R = H

221

223: Disorazole C1 222](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-33-320.jpg)

![The Sonogashira Coupling: Dynemicin

MeO2CN

OMe

Me

O

O

Br

MeO2CN

OMe

Me

O

[Pd(PPh3)4] (2 mol%)

CuI (20 mol%)

toluene, 25 °C

I nt ramolecular O

Sonogashira

Coupling

243 244

MeO2CN

OMe

Me

O

O

H

H

244

H

H

MeO2CN

OMe

Me

OH

246

Br

1) CO2Me

[Pd(PPh3)4] (2 mol %)

CuI (20 mol %)

toluene, 25 °C

2) LiOH, THF/H2O

65% overall

Sonogashira

Coupling

MeO2CN

2,4,6-Cl3C2H2COCl

DMAP, toluene, 25 °C

OMe

Me

Diels-

Alder

CO2H

OH

50%

248

247

Yamaguchi

Macrolactonisat ion/

Diels-Alder

HN

OMe

Me

H

O

O

O

OMe

OMe

CO2Me

OMe

dynemicin

249: t ri-O- methyl dynemicin A

met hyl est er

a) J. Taunton, J. L. Wood, S. L. Schreiber, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 10 378 – 10379

b) J. L. Wood, J. A. Porco, Jr., J. Taunton, A. Y. Lee, J. Clardy, S. L. Schreiber, J. Am. Chem. Soc.

1992, 114, 5898 – 5900

c) H. Chikashita, J. A. Porco, Jr., T. J. Stout, J. Clardy, S. L. Schreiber, J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 1692 – 1694

d) J. A. Porco, Jr., F. J. Schoenen, T. J. Stout, J. Clardy, S. L. Schreiber, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 7410 – 7411.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-34-320.jpg)

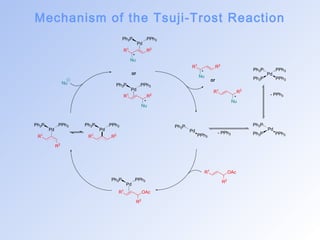

![The Tsuji-Trost Reaction

• The palladium catalysed nucleophilic substitution of allylic

compounds was discovered independently by Trost and Tsuji, and

represents the first example of a metalated species acting as an

electrophile.[22]

• Originally developed as a stoichiometric process, Trost succeeded in

transforming the allylation of enolates with p-allyl–palladium

complexes into the catalytic process of renown.[23,24]

• A wide range of allylic substrates undergo this reaction with a

correspondingly wide range of carbanions, making this a versatile

and important process for the formation of carbon–carbon bonds.

• Whilst the most commonly employed substrates for palladium-catalyzed

allylic alkylation are allylic acetates, a variety of leaving

groups also function effectively—these include halides, sulfonates,

carbonates, carbamates, epoxides, and phosphates.

cat. [Pd0Ln]

X NuH Nu

base

X = Br, Cl, OCOR, OCO2R, CO2R, P(=O)(OR)2

NuH = b-dicarbonyls, b-ketosulfones, enamines, enolates

22. For early reviews of the Tsuji-Trost reaction, see a) B. M. Trost, Acc. Chem. Res. 1980, 13, 385 – 393; b) J. Tsuji, Tetrahedron 1986,

42, 4361 – 4401.

23. J. Tsuji, H. Takahashi, Tetrahedron Lett. 1965, 6, 4387 – 4388.

24. For recent reviews of the palladium-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation reaction, see: a) B. M. Trost, M. L. Crawley, Chem. Rev. 2003,

103, 2921 – 2943; b) B. M. Trost, J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 5813 – 5837.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-35-320.jpg)

![The Tsuji-Trost Reaction: Strychnine

O

PdL AcO O OMe n

O

tBuO CO2Et

[Pd2(dba)3] (1 mol%)

PPh3 (15 mol%)

NaH, THF, 23 °C

[-CO2, -MeO ]

Tsuj i-Trost

React ion

AcO

O

tBuO CO2Et

Me

N

O

st rychnine

H

H

H

H

a) S. D. Knight, L. E. Overman, G. Pairaudeau, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 9293 – 9294

b) S. D. Knight, L. E. Overman, G. Pairaudeau, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5776 – 5788.

AcO

OtBu

O

H

CO2Et

91%

Me3Sn

TIPSO

OtBu

[Pd2(dba)3] (3 mol%)

AsPh3 (22 mol%), CO (50 psi)

LiCl, NMP, 70 °C

80%

Carbonylat ive

St ille Coupling

TIPSO

OtBu

O

N

MeN

N

O O

250

251

252

253

MeN

N

NMe

O

I

256: St rychnine 255 254](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-37-320.jpg)

![OTBS

O

PhO2S

MeO2C

The Tsuji-Trost Reaction: Roseophilin

[Pd2(dba)3] (1 mol%)

PPh3 (15 mol%)

NaH, THF, 23 °C

Tsuj i-Trost

Macrocyclisat ion

LnPd O

TBSO

PhO2S

MeO2C

LnPd OH

TBSO

PhO2S

MeO2C

263 264 265

PhO2S PhO2S

O O

O

MeO2C HO

OTBS

-[Pd0Ln]

85%

BnNH2

[Pd(PPh3)4] (15 %)

THF, 35 °C, 70%

Tsuj i-Trost

O React ion

PhO2S

NBn

HO

268 267 266

Roseophilin

N

Me

O

Me

MeO

Cl NH

269: Roseophilin

a) A. Fürstner, H. Weintritt, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 2817 – 2825;

b) A. Fürstner, T. Gastner, H. Weintritt, J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 2361 – 2366.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-38-320.jpg)

![The Tsuji-Trost Reaction: Hamigeran B

Pd

Me

P P

b

Me

B. M. Trost, C. Pissot-Soldermann, I. Chen, G.M. Schroeder, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 4480 – 4481.

O

OtBu

OAc

[{h3-C3H5PdCl} 2] (1 mol%)

ligand 285 (2 mol%)

LDA, tBuOH, Me3SnCl

DME, 25 °C

O

Asymmet ric

Allylic Alkylat ion Me

tBuO

P P

Pd

a

*

*

O

OtBu

77%, 93% ee

OMe O

Me OTf

Me

Me Me

Pd(OAc) (10 mol%)

dppb (20 mol%)

K2CO3

toluene, 110 °C, 58%

I nt ramolecular

Heck React ion

OMe O

Me H

Me

Me

Me

OMe O

Me H

Me

Me

Me

NH

O

P

Ph

Ph

HN

O

P

Ph

Ph

hamigeran B

285

284

286

287

288

290: hamigeran 289](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-39-320.jpg)

![The Tsuji-Trost Reaction: (+)-g-lycorane

* 66%, 54% ee

OBz

BzO OBz

NH

291

MeO2C

O

O

O Br

[Pd2(OAc)3] (5 mol%)

293 (10 mol%)

LDA

THF/MeCN, 0 °C

Asymmet ric

Allylic Alkylat ion

O

O

Br

NH

O

MeO2C

P P

Pd

294 295

O PdLn

O

H

H

H

O H

lycorane

O

H H H

H. Yoshizaki, H. Satoh, Y. Sato, S. Nukui, M. Shibasaki, M. Mori, J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 2016 – 2021.

O

O

Br

NH

O

MeO2C

OBz

Pd(OAc) (5 mol%)

dppb (20 mol%)

NaH

DMF, 50 °C

I nt ramolecular

Allylic Alkylat ion/

Heck React ion

Cascade

O

O

Br

N

MeO2C

O O

Br

N

MeO2C

H

iPr2NEt, 100 °C

O O

N

CO2Me

O

N

299: (+ ) -g-lycorane

298

297 296

292

O

O

PPh2

PPh2

293](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-40-320.jpg)

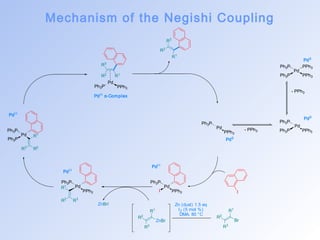

![The Negishi Coupling

• The use of organozinc reagents as the nucleophilic component in

palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, known as the Negishi

coupling, actually predates both the Stille and Suzuki processes,

with the first examples published in the 1970s.[25]

• However, the stunning progress in the latter procedures left the

Negishi process behind, underappreciated and underutilised.

• Organozinc reagents exhibit a very high intrinsic reactivity in

palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, which combined with

the availability of a number of procedures for their preparation and

their relatively low toxicity, makes the Negishi coupling an

exceedingly useful alternative to other cross-coupling procedures, as

well as constituting an important method for carbon–carbon bond

formation in its own right.[26]

ZnR2 R1 R3

25. a) E. Negishi, A. O. King, N. Okukado, J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 1821 – 1823; for a discussion, see: b) E. Negishi, Acc. Chem. Res.

1982, 15, 340 – 348.

26. a) E. Erdik, Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 9577 – 9648; b) E. Negishi, T. Takahashi, S. Babu,D. E. Van Horn, N. Okukado, J. Am. Chem. Soc.

1987, 109, 2393 – 2401.

R1 R3 X

cat. [Pd0Ln]

R1 = alkyl, alkynyl, aryl, vinyl

R3 = acyl, aryl, benzyl, vinyl

X = Br, I, OTf, OTs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-41-320.jpg)

![The Negishi Coupling: Discodermolide

Me

Me

Me

Me

309 310 312

Me

discodermolide

Me

O O

O

HO

a) A. B. Smith III, T. J. Beauchamp, M. J. LaMarche, M. D. Kaufman, Y. Qiu, H. Arimoto, D. R. Jones, K. Kobayashi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000,

122, 8654 – 8664;

b) A. B. Smith III, M. D. Kaufman, T. J. Beauchamp,M. J. LaMarche, H. Arimoto, Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 1823 – 1826.

c) For a review of the chemistry and biology of discodermolide, see: M. Kalesse, ChemBioChem 2000, 1, 171 – 175

d) For examples of other approaches to discodermolide, see: I. Paterson, G. J. Florence, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 2193 – 2208.

e) In the synthesis of discodermolide by the Marshall group, a B-alkyl Suzuki–Miyarua fragment-coupling strategy was employed to form the

C14C15 bond, in which 2.2 equivalents of an alkyl iodide structurally related to 309 was required: J. A. Marshall, B. A. Johns, J. Org.

Chem. 1998, 63, 7885 – 7892.

I

Me Me

TBSO O O

PMP

tBuLi, ZnCl2

Et2O

-78 °C Zn

Me Me

TBSO O O

PMP

[Pd(PPh3)4] (5 mol%)

311

Et2O, 25 °C, 66%

Negishi Coupling

Me Me

OTBS O O

PMP

Me

PMBO

Me

OTBS

I

PMBO

Me

OTBS

Me

= 311

Me Me

OH O

Me

Me Me

OH

NH2

HO

Me

HO

313: discodermolide

15 15

15

14

14

15

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-43-320.jpg)

![The Negishi Coupling: Amphidinolide T1

Cl O

Me

O

O

Me

TBDPSO Me

O

Me

OMOM

R

314: R = ZnI

(315: R = I)

(316: R = H)

[Pd2(dba)3] (3 mol%)

285

P(2-furyl)3 (6 mol %)

toluene/DMA, 25 °C, 50%

Negishi Coupling

Me O

amphidinolide

a) C. Aïssa, R. Riveiros, J. Ragot, A. Fürstner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 15 512 – 15520.

OMOM

TBDPSO Me

Me

O

O

Me

O

Me O

OMOM

TBDPSO Me

O

Me Me

O

O

317

318

319: Amphidinolide T1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-44-320.jpg)

![The Fukuyama Coupling

• The Fukuyama Coupling is a

modification of the Negishi

Coupling, in which the electrophilic

component is a thioester.

• The product of the coupling with a

Negishi-type organozinc reagent is

carbonyl compound, thus negating

the need for a carbon monoxide

atmosphere.

O

SR4

R1 R3 cat. [Pd0Ln]

ZnR2 R1 R3

R1 = alkyl, alkynyl, aryl, vinyl

R3 = acyl, aryl, benzyl, vinyl

R4 = Me, Et, et c.

O ZnI [PdCl2(PPh3)2] (10 mol%)

27) H. Tokuyama, S. Yokoshima, T. Yamashita, S.-C. Lin, L. Li, T. Fukuyama, J. Braz. Chem. Soc., 1998, 9, 381-387.

O

MeO

SEt

toluene, 25 °C, 5 min, 87%

Fukuyama Coupling MeO

O](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-45-320.jpg)

![Palladium Catalysis: Outlook And Summary

• This review has highlighted only a small number of applications of palladium catalysis in organic

synthesis, but new examples are published every month.

• Each example pushes the field forwards, towards universal conditions, where application of them

results in a useful yield without prior optimisation.

• However, palladium is only one metal; the breadth of catalysis available from rhodium,[28]

ruthenium[29] and platinum based systems extend far further, and into the realms of metathesis.[30]

Fürstner has shown analogous procedures using Iron catalysts,[31] with obvious economic and

toxicity benefits.

28) For an example of palladium-mimicking rhodium catalysis, see: M. Lautens and J. Mancuso, Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 2105

29) For a recent review of "atom ecconomic" ruthenium catalysis, see: B. M. Trost, M. U. Frederiksen, M. T. Rudd, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.,

2005, 41, 6630 – 6666.

30) For the complementary review on Metathesis Reactions in Total Synthesis, see: K. C. Nicolaou, P. G. Bulger, D. Sarlah , Angew. Chem. Int.

Ed., 2005, 41, 4490-4527.

31) A. Fürstner, R. Martin, Chem. Lett. 2005, 34, 624-629.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/palladiumcatalysedreactionsinsynthesis-141014223547-conversion-gate02/85/Palladium-catalysed-reactions-in-synthesis-46-320.jpg)