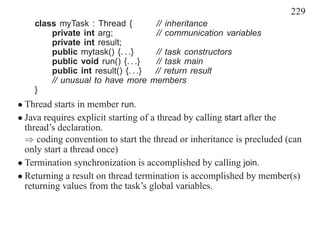

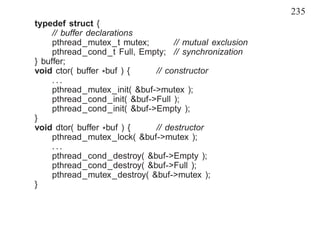

The document discusses several programming languages and libraries that provide concurrency constructs for parallel programming. It describes features for concurrency in Ada 95, Java, and C/C++ libraries including pthreads. Key features covered include threads, mutual exclusion locks, condition variables, and examples of implementing a bounded buffer for inter-thread communication.