This document provides an overview of the book "On Call Radiology" which presents case discussions on common clinical emergencies and their corresponding imaging findings encountered on-call. The book combines a case-based discussion format with practical advice on imaging decision making in the acute setting and guidance on radiology report writing. It discusses various conditions organized by body system including thoracic, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, neurological and trauma imaging. Each case includes a clinical history, imaging examples, diagnosis and basic management discussion.

![CRC Press

Taylor & Francis Group

6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300

Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742

© 2016 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business

No claim to original U.S. Government works

Version Date: 20150514

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4822-2168-8 (eBook - PDF)

This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. While all reasonable efforts have

been made to publish reliable data and information, neither the author[s] nor the publisher can accept any legal respon-

sibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. The publishers wish to make clear that any views or

opinions expressed in this book by individual editors, authors or contributors are personal to them and do not neces-

sarily reflect the views/opinions of the publishers. The information or guidance contained in this book is intended for

use by medical, scientific or health-care professionals and is provided strictly as a supplement to the medical or other

professional’s own judgement, their knowledge of the patient’s medical history, relevant manufacturer’s instructions and

the appropriate best practice guidelines. Because of the rapid advances in medical science, any information or advice on

dosages, procedures or diagnoses should be independently verified. The reader is strongly urged to consult the relevant

national drug formulary and the drug companies’ and device or material manufacturers’ printed instructions, and their

websites, before administering or utilizing any of the drugs, devices or materials mentioned in this book. This book

does not indicate whether a particular treatment is appropriate or suitable for a particular individual. Ultimately it is

the sole responsibility of the medical professional to make his or her own professional judgements, so as to advise and

treat patients appropriately. The authors and publishers have also attempted to trace the copyright holders of all mate-

rial reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been

obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any

future reprint.

Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or uti-

lized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopy-

ing, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the

publishers.

For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright.com (http://

www.copyright.com/) or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923,

978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users. For

organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by the CCC, a separate system of payment has been arranged.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for

identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Visit the Taylor & Francis Web site at

http://www.taylorandfrancis.com

and the CRC Press Web site at

http://www.crcpress.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oncallradiology-180422160240/85/On-call-radiology-6-320.jpg)

![Chapter 286

narrowing. Similarly, an increase in the peak systolic

velocity may also be observed. Severely stenotic arteries

mayeventuallythromboseandshownoflow.Pulse-wave

Doppler classically shows a ‘parvus-tardus’ waveform in

stenosed vessels (i.e. increased peak systolic acceleration

time [0.08 sec] with a slow deceleration) (Figure 2.89).

The RI is a measure of the resistance to blood flow

and can also be a useful tool in the assessment of the

post-transplantliver(see Figure 2.85,p.83).NormalRI

values range between 0.5 and 0.8. In the postoperative

period, RI values may be elevated for several days, but

they should generally reduce to normal limits. Elevated

RI values may be a sign of organ rejection or venous

outflow obstruction.

Portal vein abnormalities are relatively rare. The

commonest complications include portal vein stenosis

and thrombosis. The normal portal vein is anechoic

with thin, regular walls and uniform calibre. Acute

thrombus within the portal vein may present as

echogenic material within the lumen of the vessel with

reduced or no flow on colour Doppler.

Complications involving the IVC are uncommon

but include thrombosis and IVC stenosis at the

anastomotic site. Clinical features are those of Budd–

Chiarisyndromeandincludehepatomegaly,ascitesand

pleural effusions, which may be seen on ultrasound.

Biliary complications are relatively common

following transplant and include leaks and stricture

non-specific, but may be seen as a heterogeneous

echotexture. In cases of rejection, there are often no

correlatingfeatureswithDopplerstudies.Liverinfarcts

occurmostcommonlyintheearlypostoperativeperiod,

and present as focal, wedge-shaped areas of decreased

echogenicity. Abnormal Doppler waveforms may be

recorded in cases of infarction.

Hepatic artery complications account for the largest

proportion of vascular complications, which include

thrombosis and stenosis. Hepatic artery thrombosis is

a surgical emergency due to the high risk of ischaemia

and infarction to the transplant. In addition to this,

the bile ducts receive their blood supply solely from

the hepatic artery, and so thrombosis of the vessel may

lead to biliary duct ischaemia and stricture formation.

An appreciation of the normal hepatic artery flow and

waveform is useful in order to identify abnormalities.

The normal hepatic artery demonstrates a pulsatile

waveformwitharapidsystolicupstrokeandcontinuous

diastolic blood flow (Figure 2.88).

Absent flow within the hepatic artery with colour

and pulse-wave Doppler imaging allows for correct

diagnosisofhepaticarterythrombosisinthemajorityof

cases. Assessment should be made of the extrahepatic,

intrahepatic and right and left branches of the artery.

Hepatic artery stenosis tends to occur at the site of

the anastomosis. Colour flow may demonstrate post-

stenotic turbulent flow depending on the degree of

Figure 2.88 Doppler ultrasonogram of the hepatic

artery. The waveform demonstrates a sharp systolic

upstroke and short deceleration time with continuous

diastolic flow. Measurements have been made

documenting the peak systolic and end diastolic values

with the calculated Resistive Index of 0.63.

Figure 2.89 Doppler ultrasonogram of a stenotic

hepatic artery. The deceleration time of the waveform is

prolonged resulting in a ‘parvus-tardus’ waveform.

K22247_C002.indd 86 16/05/15 3:07 AM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oncallradiology-180422160240/85/On-call-radiology-108-320.jpg)

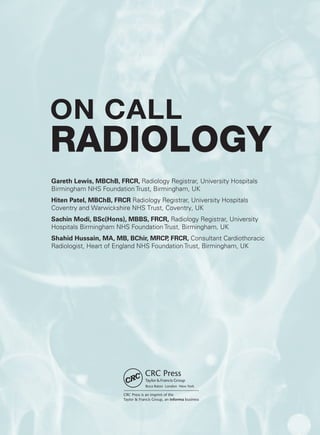

![203

Appendix 1

CRITERIA FOR PERFORMING A CT

HEAD SCAN

[1] For adults who have sustained a head injury and have any of the following risk factors, perform a

CT head scan within 1 hour of the risk factor being identified:

• GCS less than 13 on initial assessment in the emergency department.

• GCS less than 15 at 2 hours after the injury on assessment in the emergency department.

• Suspected open or depressed skull fracture.

• Any sign of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, ‘panda’ eyes, cerebrospinal fluid leakage from the

ear or nose, Battle’s sign).

• Post-traumatic seizure.

• Focal neurological deficit.

• More than 1 episode of vomiting.

• A provisional written radiology report should be made available within 1 hour of the scan being

performed.

[2] For children who have sustained a head injury and have any of the following risk factors, perform

a CT head scan within 1 hour of the risk factor being identified:

• Suspicion of non-accidental injury.

• Post-traumatic seizure but no history of epilepsy.

• On initial emergency department assessment, GCS less than 14, or for children under 1 year GCS

(paediatric) less than 15.

• At 2 hours after the injury, GCS less than 15.

• Suspected open or depressed skull fracture or tense fontanelle.

• Any sign of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, ‘panda’ eyes, cerebrospinal fluid leakage from

the ear or nose, Battle’s sign).

• Focal neurological deficit.

• For children under 1 year, presence of bruise, swelling or laceration of more than 5 cm on the head.

• A provisional written radiology report should be made available within 1 hour of the scan being

performed.

[3] For children who have sustained a head injury and have more than one of the following risk factors

(and none of those listed under [2] above), perform a CT head scan within 1 hour of the risk factors

being identified:

• Loss of consciousness lasting more than 5 minutes (witnessed).

• Abnormal drowsiness.

• Three or more discrete episodes of vomiting.

• Dangerous mechanism of injury (high-speed road traffic accident either as pedestrian, cyclist or vehicle

occupant, fall from a height of greater than 3 metres, high-speed injury from a projectile or other

object).

K22247_Appendix I.indd 203 16/05/15 3:15 AM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oncallradiology-180422160240/85/On-call-radiology-225-320.jpg)

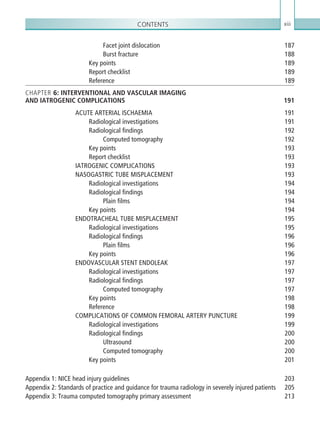

![Appendix 1204

• Amnesia (antegrade or retrograde) lasting more than 5 minutes.

• A provisional written radiology report should be made available within 1 hour of the scan being

performed.

[4] Children who have sustained a head injury and have only 1 of the risk factors listed under [3]

above (and none of those listed under [2] above) should be observed for a minimum of 4 hours after

the head injury. If during observation any of the risk factors below are identified, perform a CT head

scan within 1 hour:

• GCS less than 15.

• Further vomiting.

• A further episode of abnormal drowsiness.

• A provisional written radiology report should be made available within 1 hour of the scan being

performed. If none of these risk factors occur during observation, use clinical judgement to determine

whether a longer period of observation is needed.

GCS = Glasgow Coma Score

From National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014) CG 176 Head injury. Triage, assessment,

investigation and early management of head injury in children, young people and adults. Manchester: NICE.

Available from www.nice.org.uk/CG176. With permission.

K22247_Appendix I.indd 204 16/05/15 3:15 AM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oncallradiology-180422160240/85/On-call-radiology-226-320.jpg)