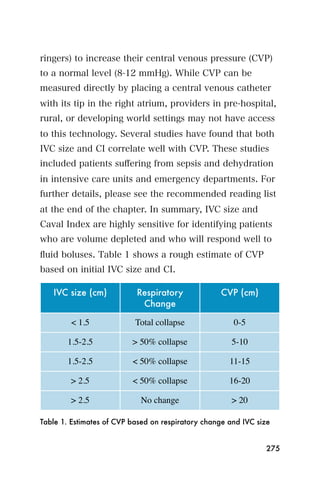

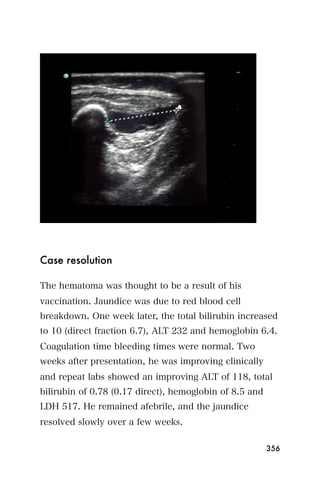

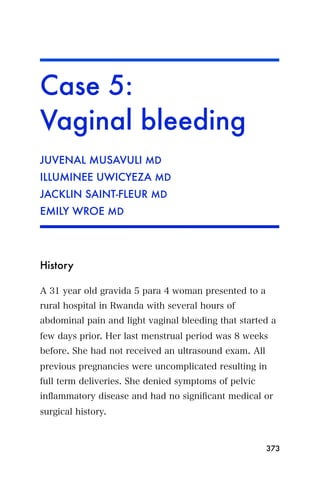

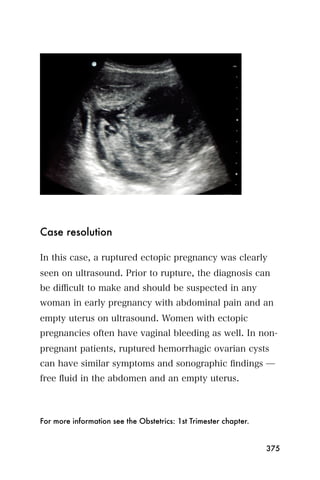

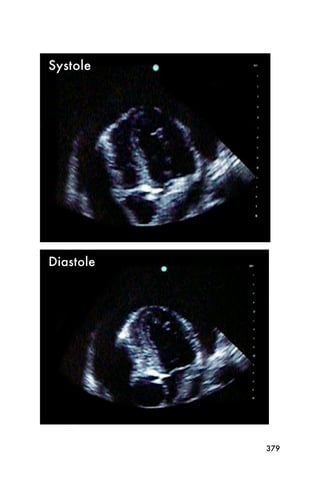

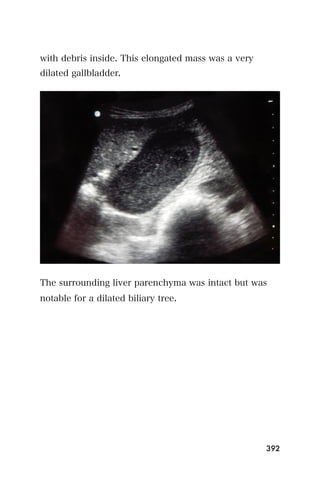

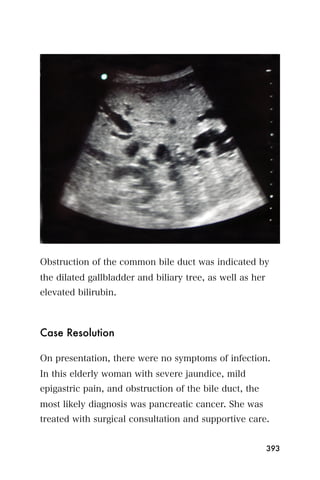

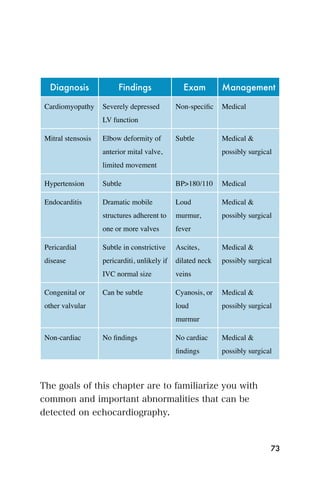

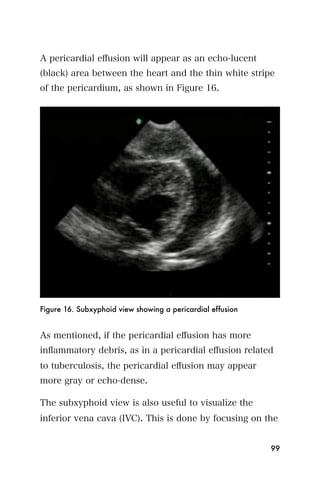

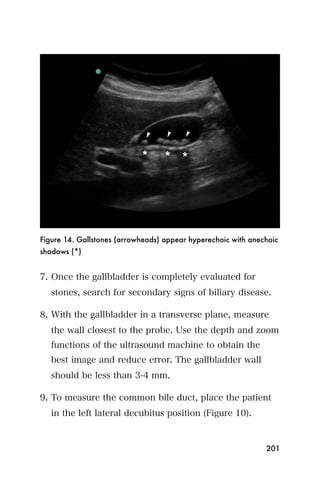

This document provides an overview and table of contents for "The Partners In Health Manual of Ultrasound for Resource Limited Settings." It was edited by Sachita P Shah and Daniel D Price and contains chapters on fundamentals of ultrasound, trauma, echocardiography, obstetrics, liver, gallbladder, spleen, kidney, abdominal aortic aneurysm, deep venous thrombosis, volume status, bladder, skin, procedures, and vascular access. It is intended as a resource for healthcare providers using point-of-care ultrasound in resource-limited settings.

![Recommended reading

1. Andrews MW. Ultrasound of the spleen. World J Surg

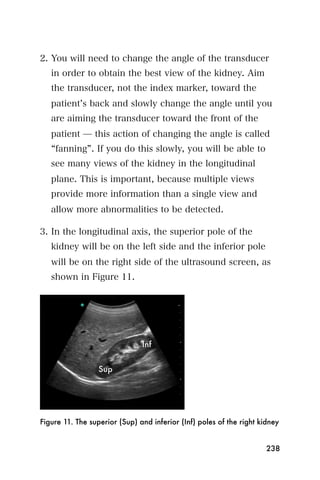

2000;24:183-7.

2. Bonnard P, Lanuit R, Dompnier JP, et al. [Predictive

ultrasonographic criteria for portal hypertension due to

Schistosoma mansoni in a recently established endemic zone].

Med Trop (Mars) 2000;60:42-6.

3. Harald T. Lutz HAG. Manual of Diagnostic Ultrasound in

Infectious Tropical Diseases. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag,

2006.

4. Richter J, de Bernardis C, Sagir A, et al. Is ultrasound a useful

adjunct for assessing malaria patients? Parasitol Res

2004;94:349-53.

5. Doehring-Schwerdtfeger E, Kaiser C, Schlake J, et al.

Ultrasound versus clinical examination as indication for

Schistosoma mansoni associated morbidity in children. Trop

Med Parasitol 1992;43:245-8.

6. Mathieson JR, Cooperberg PL. The Spleen in Diagnostic

Ultrasound. Mosby Year Book. St. Louis, MO: Mosby;

1997:154-177.

221](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/manualultrasound-120605111949-phpapp02/85/Manual-ultrasound-221-320.jpg)