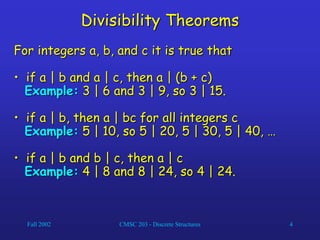

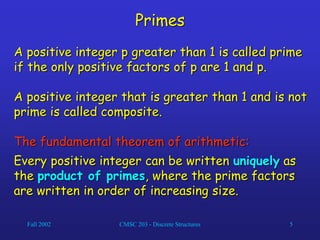

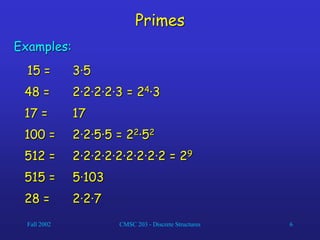

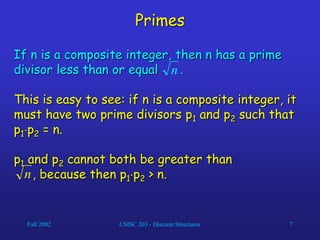

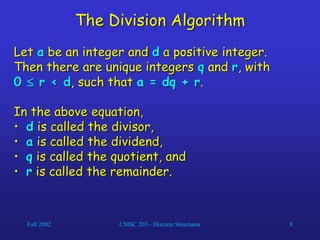

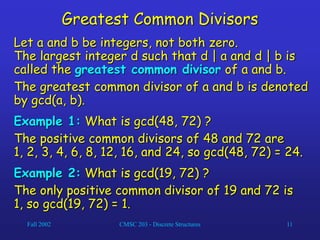

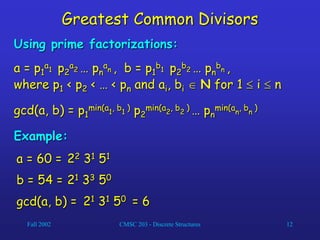

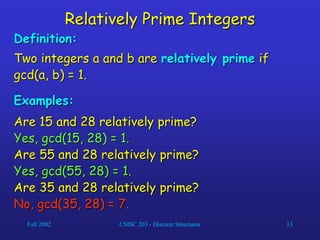

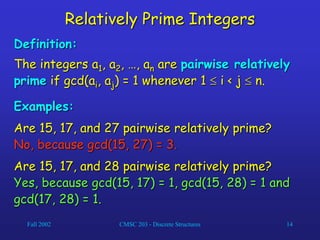

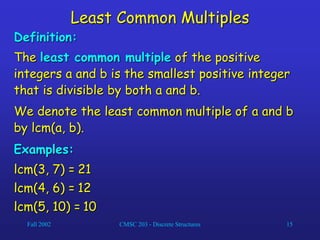

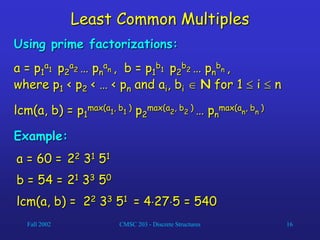

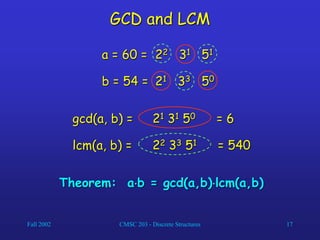

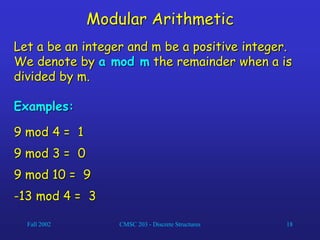

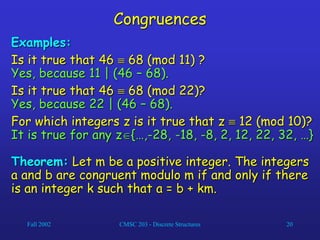

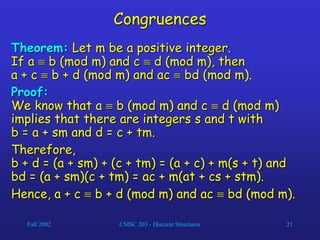

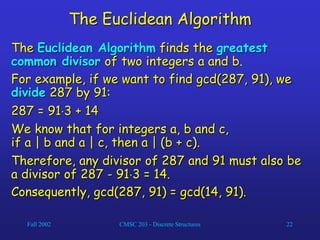

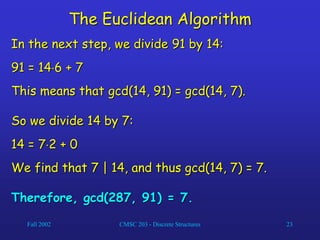

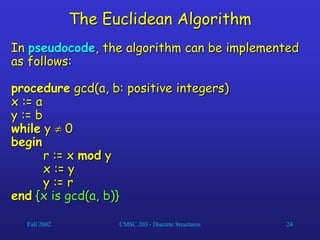

This document provides an overview of topics in number theory that will be covered in a discrete structures course, including divisibility, greatest common divisors, primes, and modular arithmetic. It introduces basic concepts such as integers dividing other integers, prime numbers, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, the Euclidean algorithm for finding greatest common divisors, and modular arithmetic involving remainders when dividing integers. Examples are provided to illustrate key definitions and properties related to these foundational number theory topics.