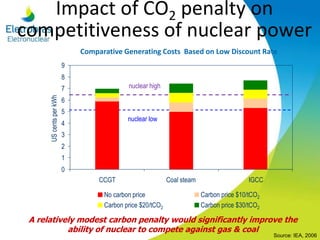

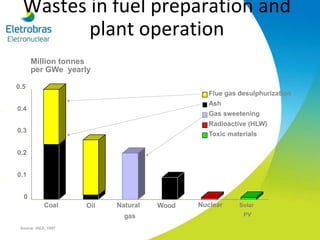

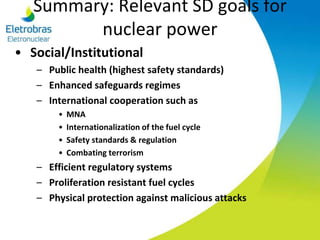

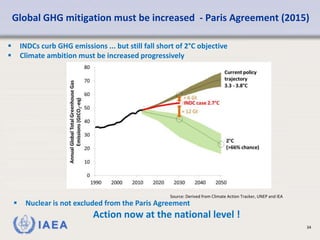

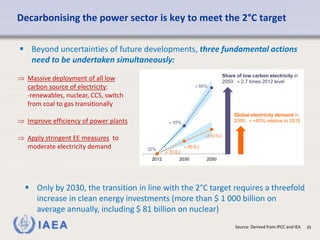

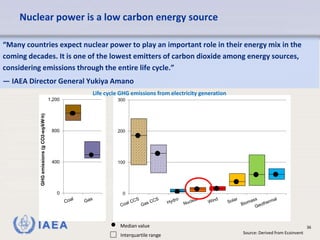

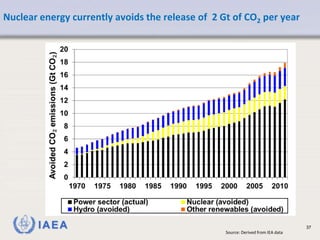

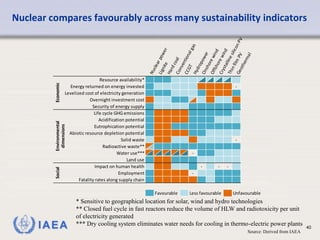

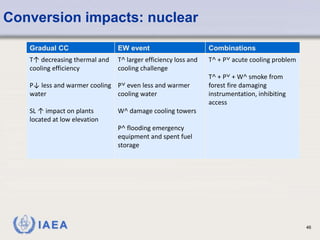

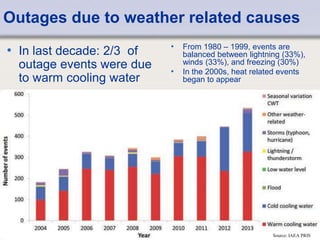

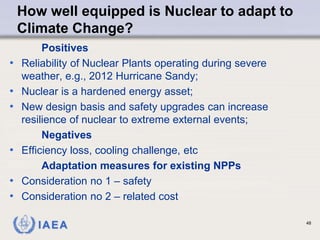

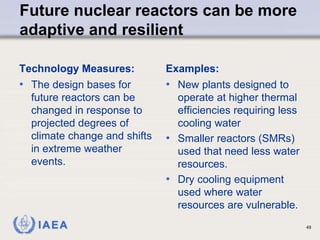

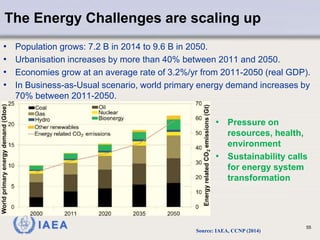

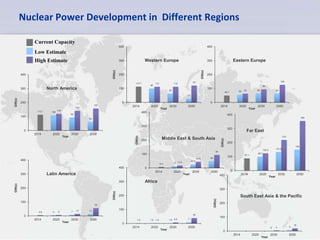

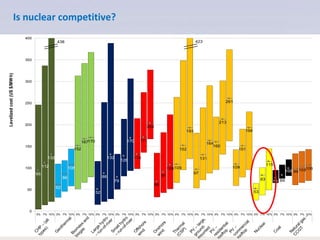

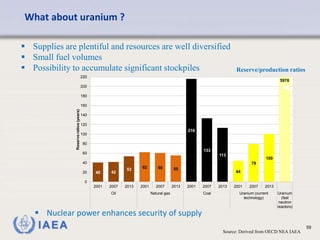

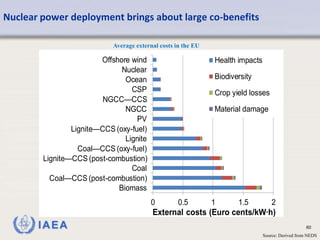

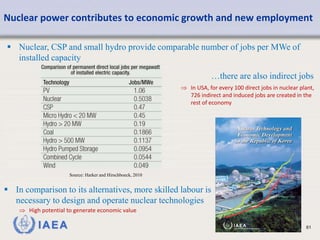

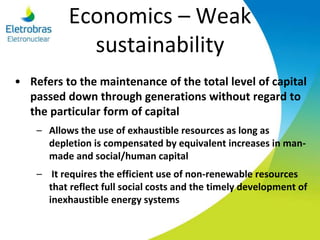

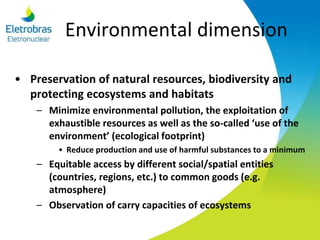

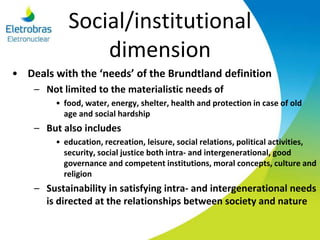

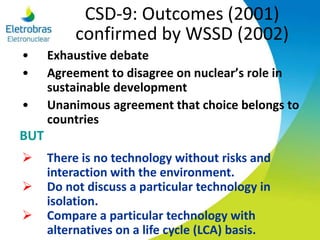

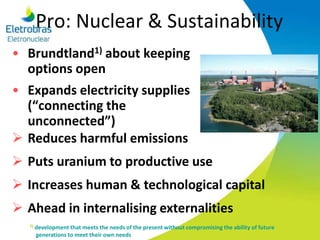

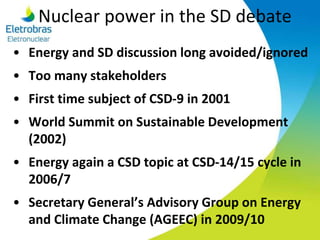

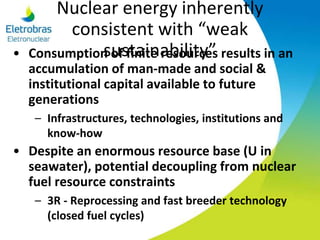

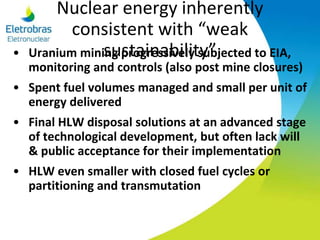

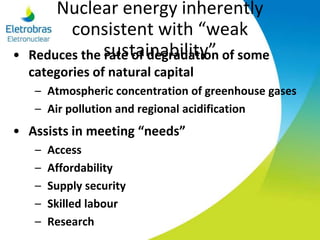

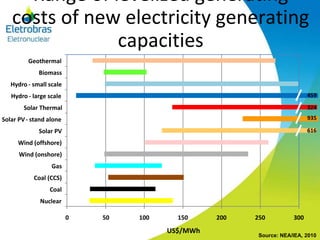

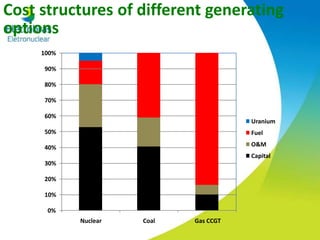

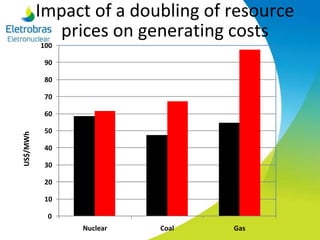

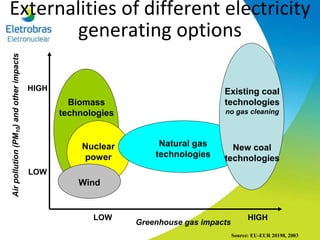

The document discusses the relationship between nuclear power and sustainable development, detailing the three pillars of sustainability: environmental, economic, and social/institutional dimensions. It highlights the debate surrounding nuclear energy's role in climate change mitigation, emphasizing its low greenhouse gas emissions and potential to expand electricity supplies while addressing waste management concerns. Ultimately, it asserts that while nuclear power has advantages in promoting sustainability, it also faces challenges such as safety risks and public acceptance.

![Mitigation – Role of nuclear

power

Life cycle GHG emissions of different electricity generating options

Nuclear power: Very low lifetime GHG emissions make

the technology a potent climate change mitigation option

[8]

[12]

[10]

[16]

[8]

0

200

400

600

800

1 000

1 200

1 400

1 600

1 800

lignite coal oil gas CCS

[8]

[12]

[10]

[16]

[8]

0

200

400

600

800

1 000

1 200

1 400

1 600

1 800

lignite coal oil gas CCS

[15][15]

[16]

[15]

[13]

[8]

[4]

Standard deviation

Mean

Min - Max

[sample size]

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

hydro nuclear wind solar

PV

bio-

mass

storage

[16]

[15]

[13]

[8]

[4]

Standard deviation

Mean

Min - Max

[sample size]

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

hydro nuclear wind solar

PV

bio-

mass

storage

gCO2-eqperkWh](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nuclearpowerandsustainabledevelopment-160729163008/85/Nuclear-power-and-sustainable-development-25-320.jpg)