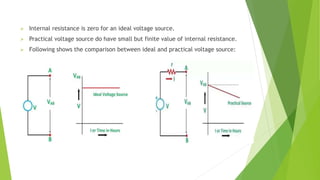

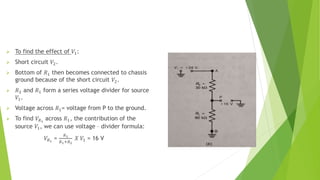

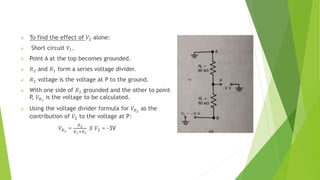

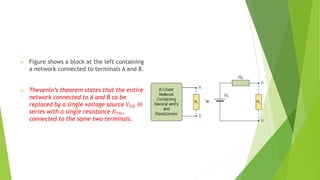

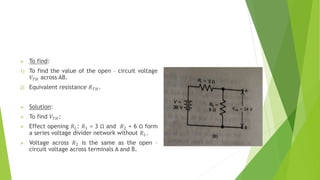

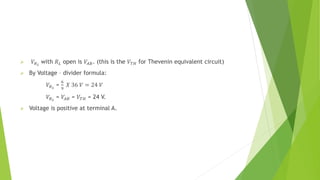

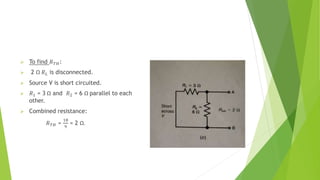

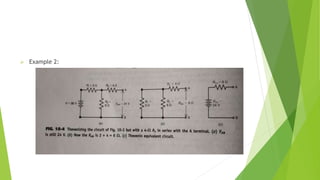

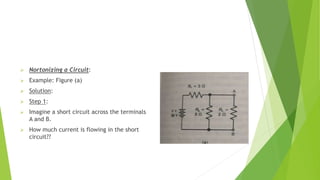

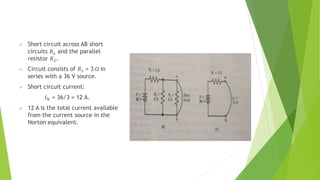

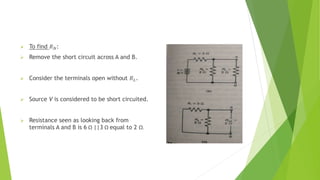

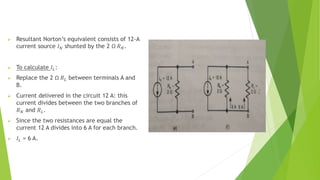

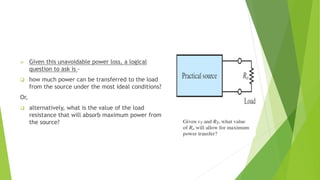

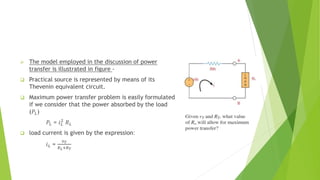

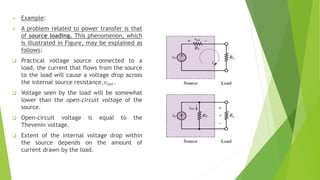

The document discusses several network theorems including superposition, Thevenin's, and Norton's theorems. Superposition theorem states that the total response of a network with multiple sources is the sum of the responses of each source acting alone. Thevenin's theorem shows that any linear network can be reduced to an equivalent circuit with a voltage source and single output resistance. Norton's theorem represents a network as a current source and parallel output resistance. Both theorems simplify analysis of complex networks. Maximum power transfer occurs when the load and source resistances are equal.