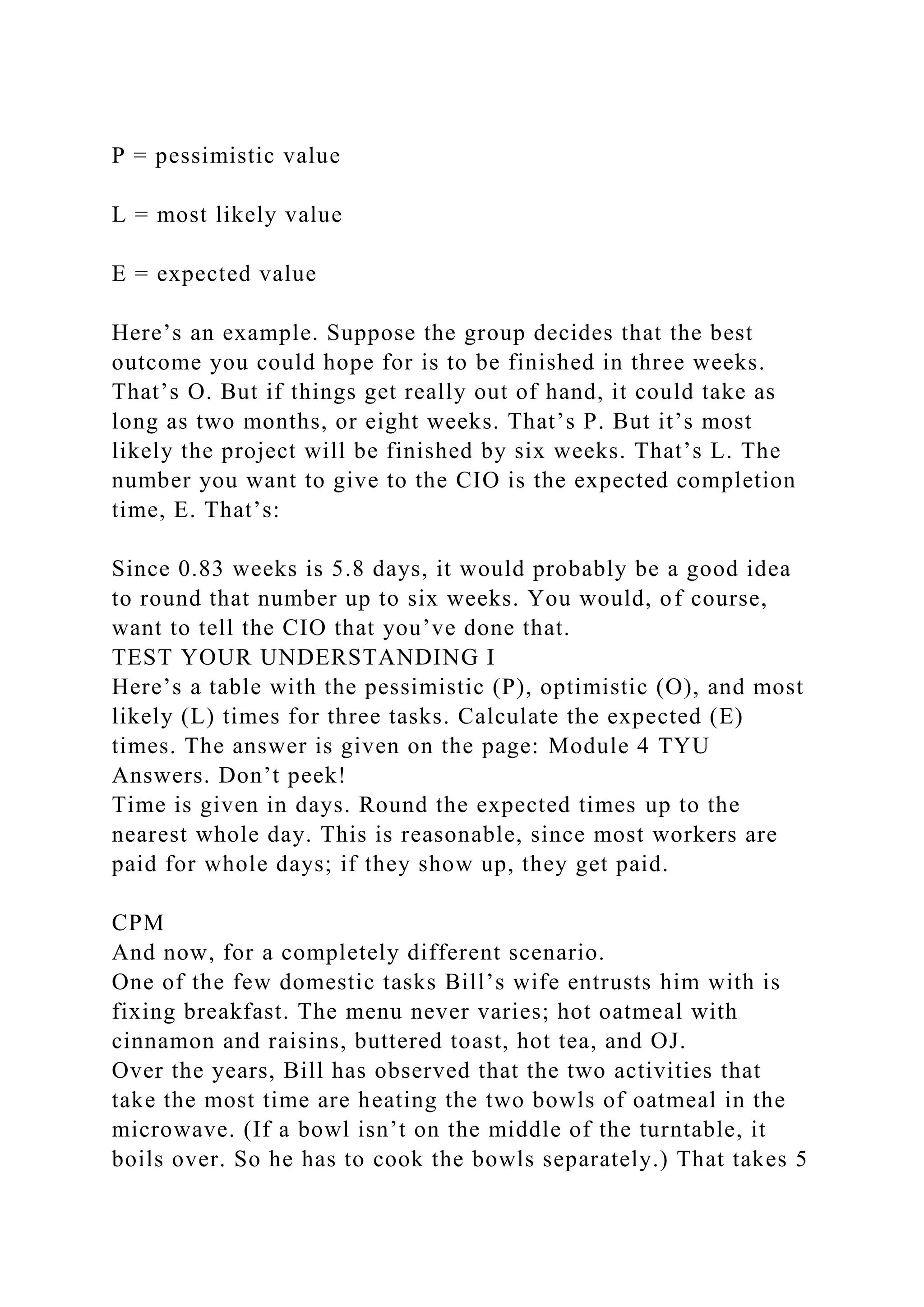

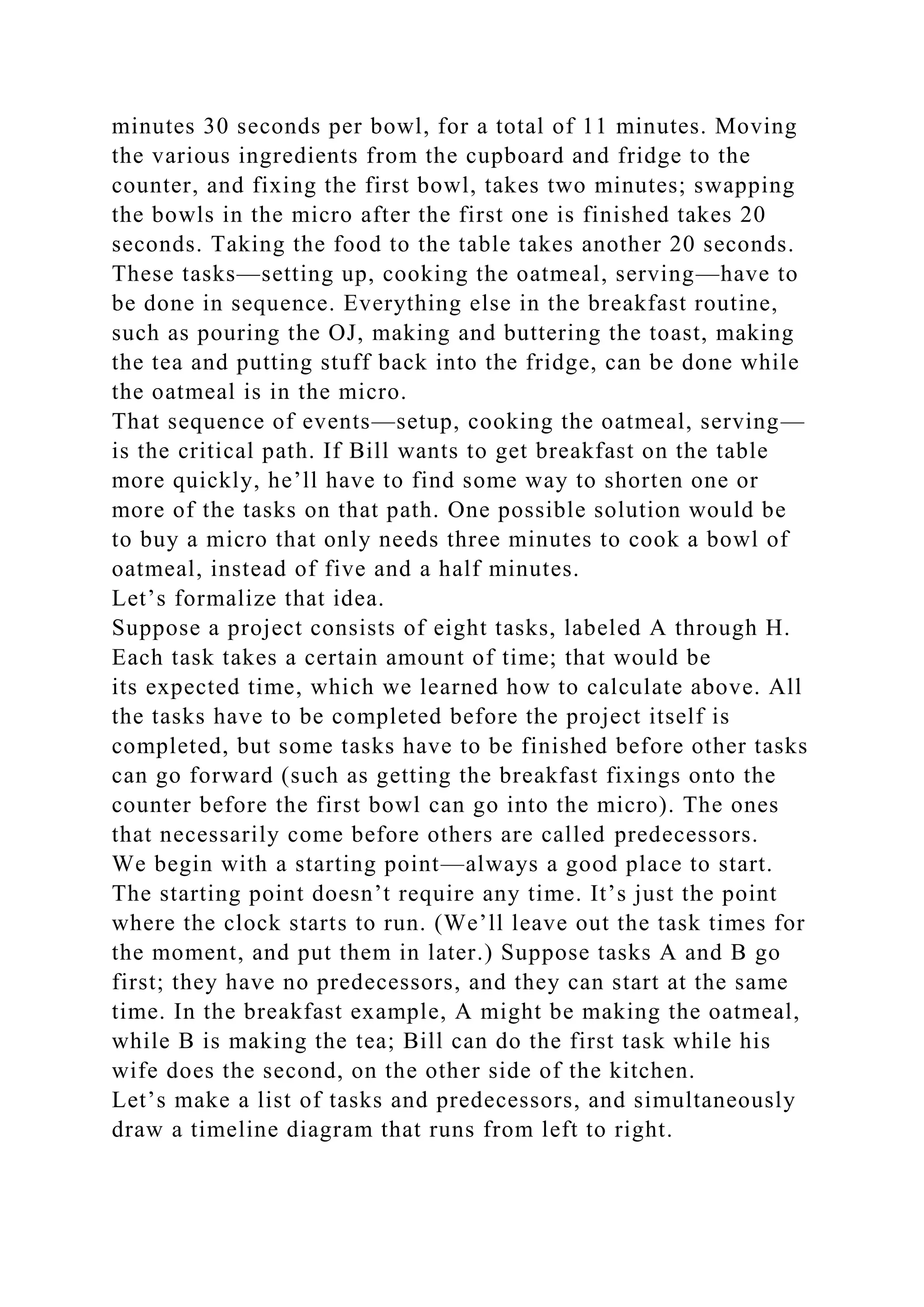

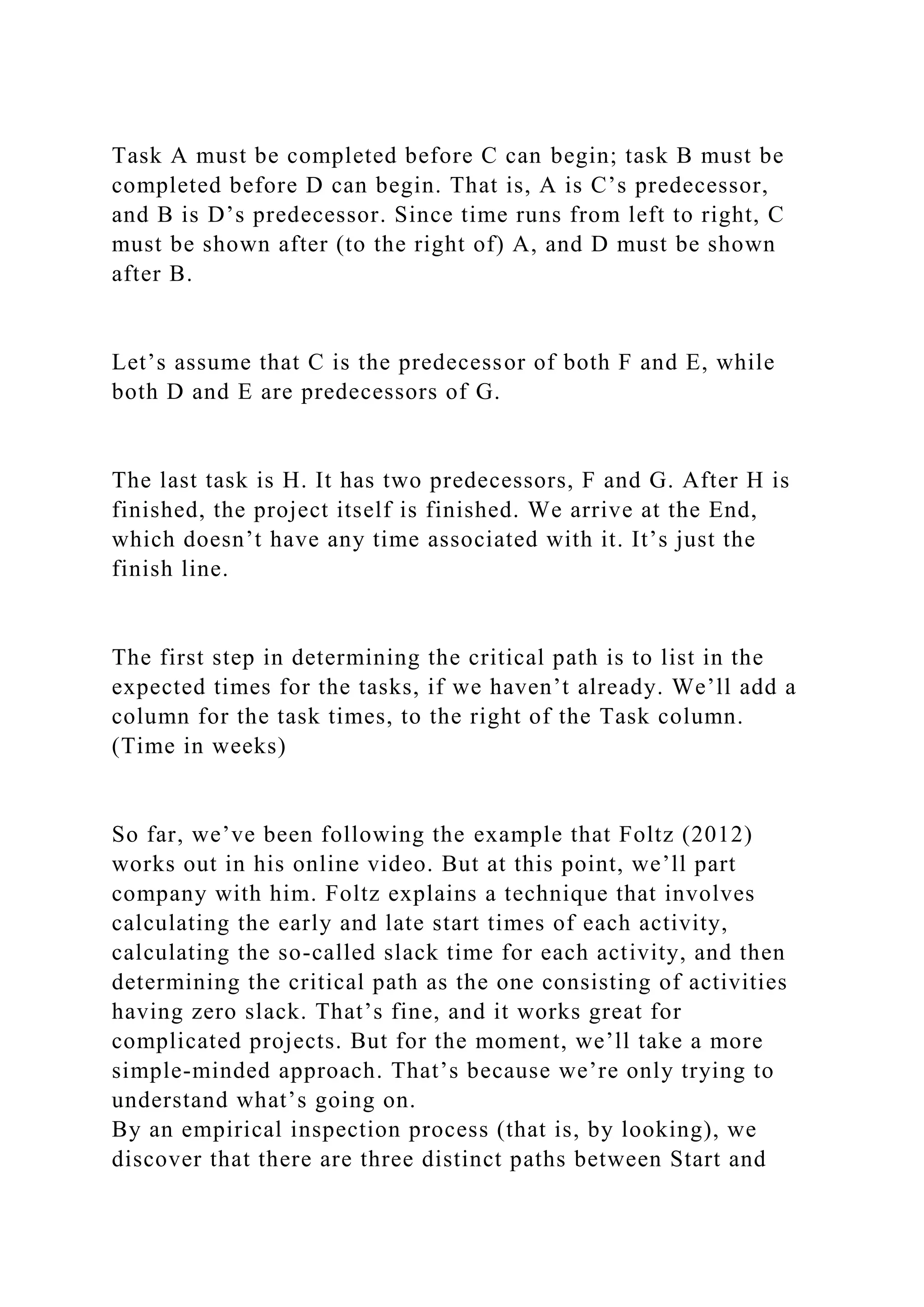

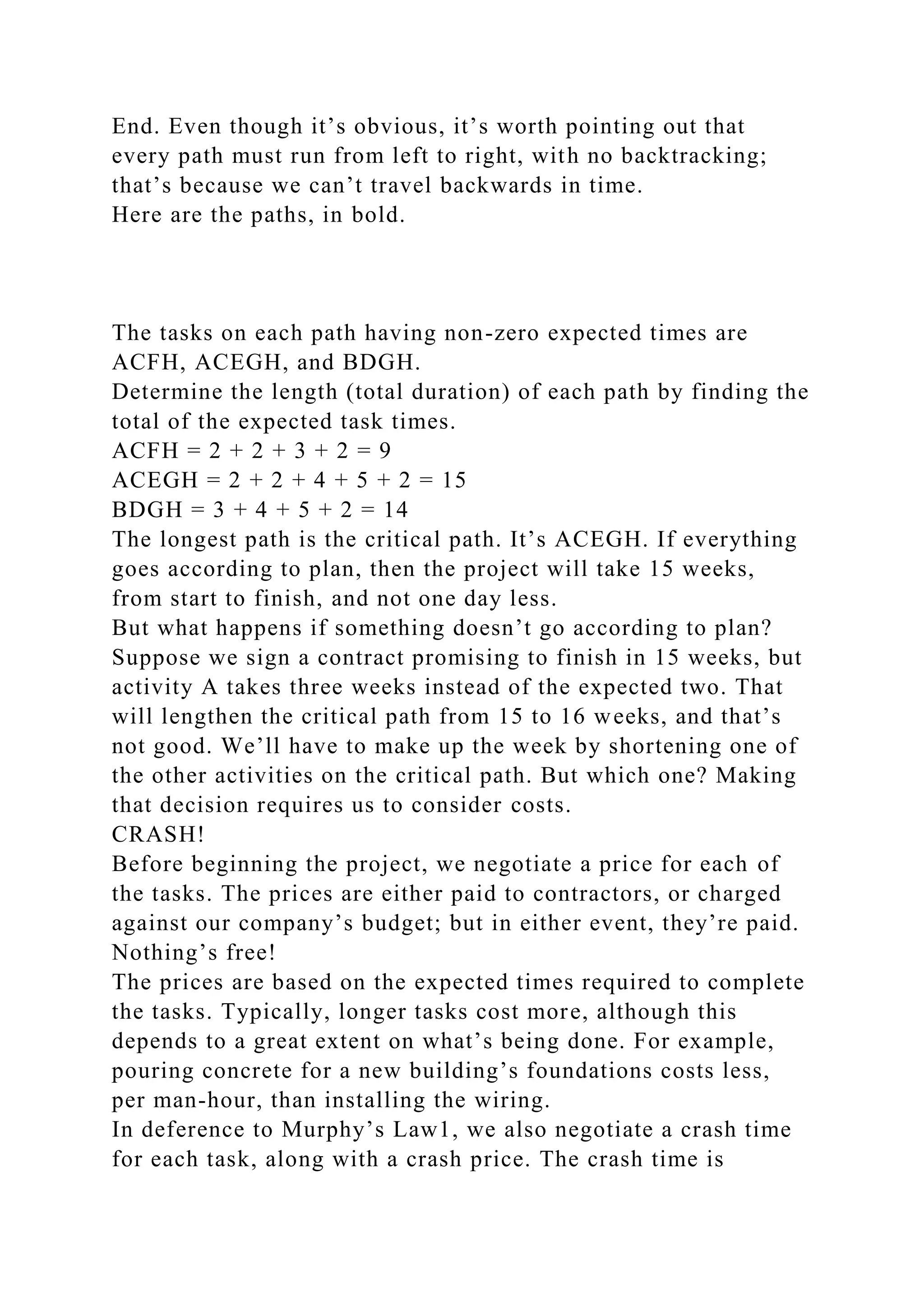

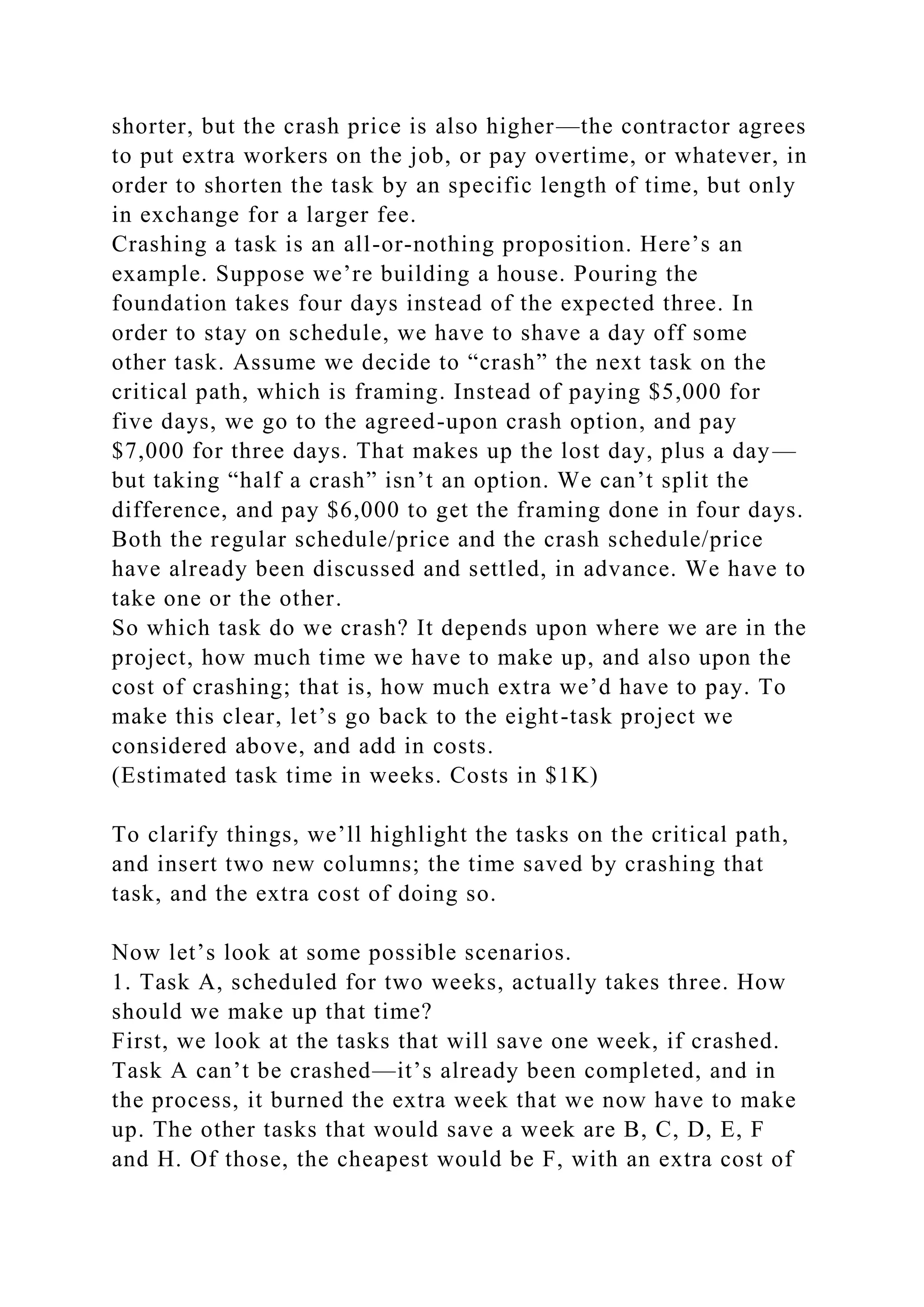

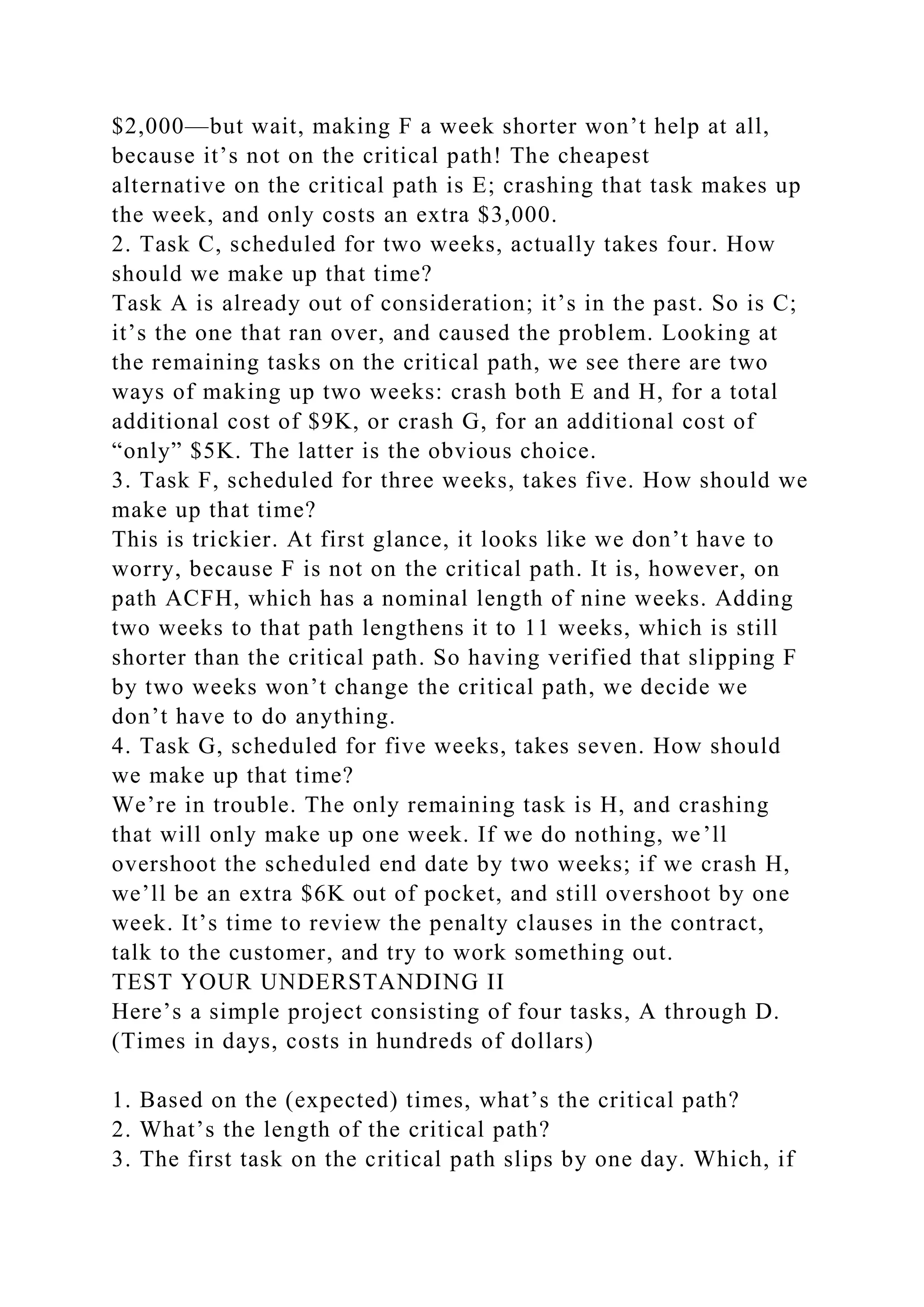

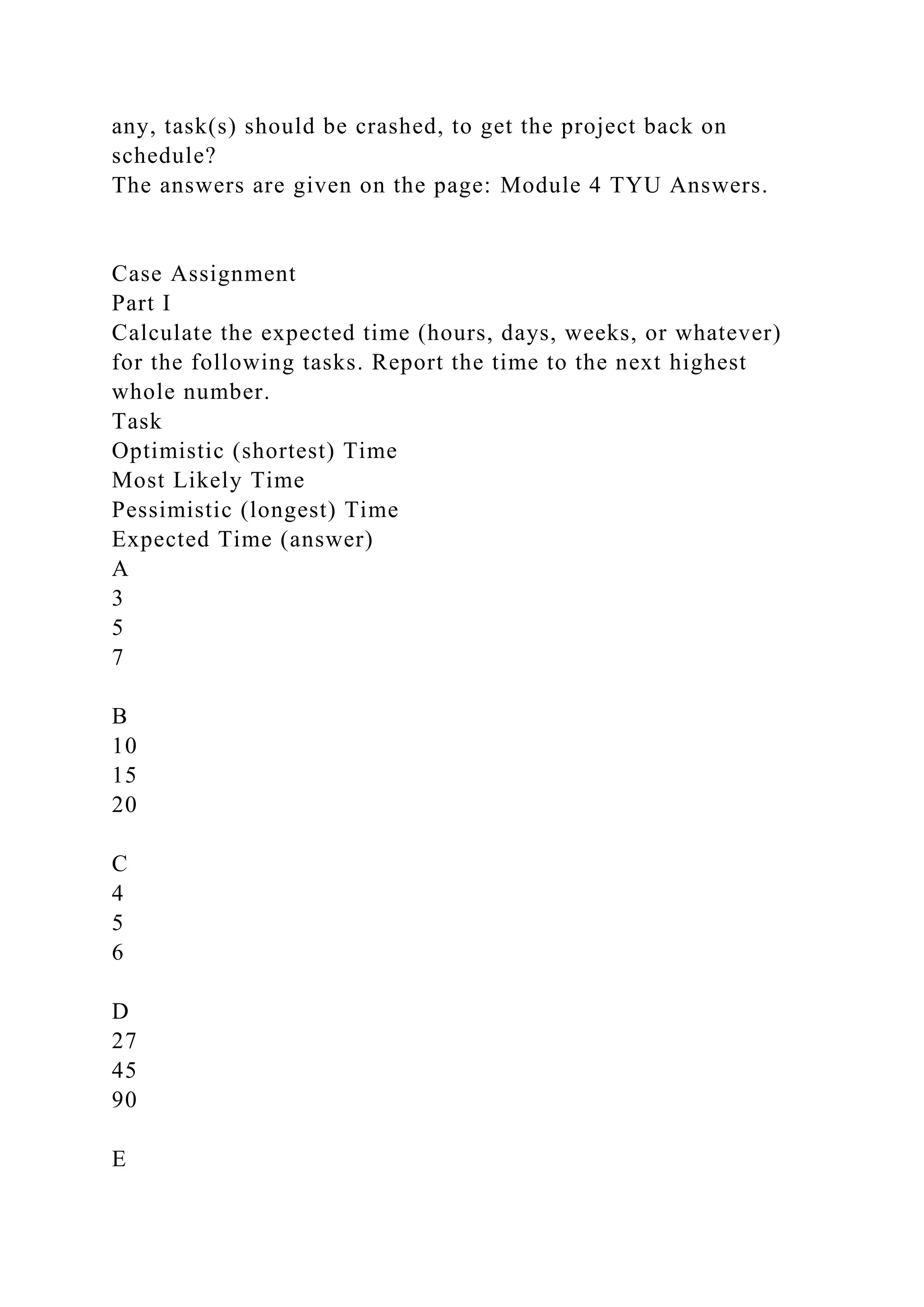

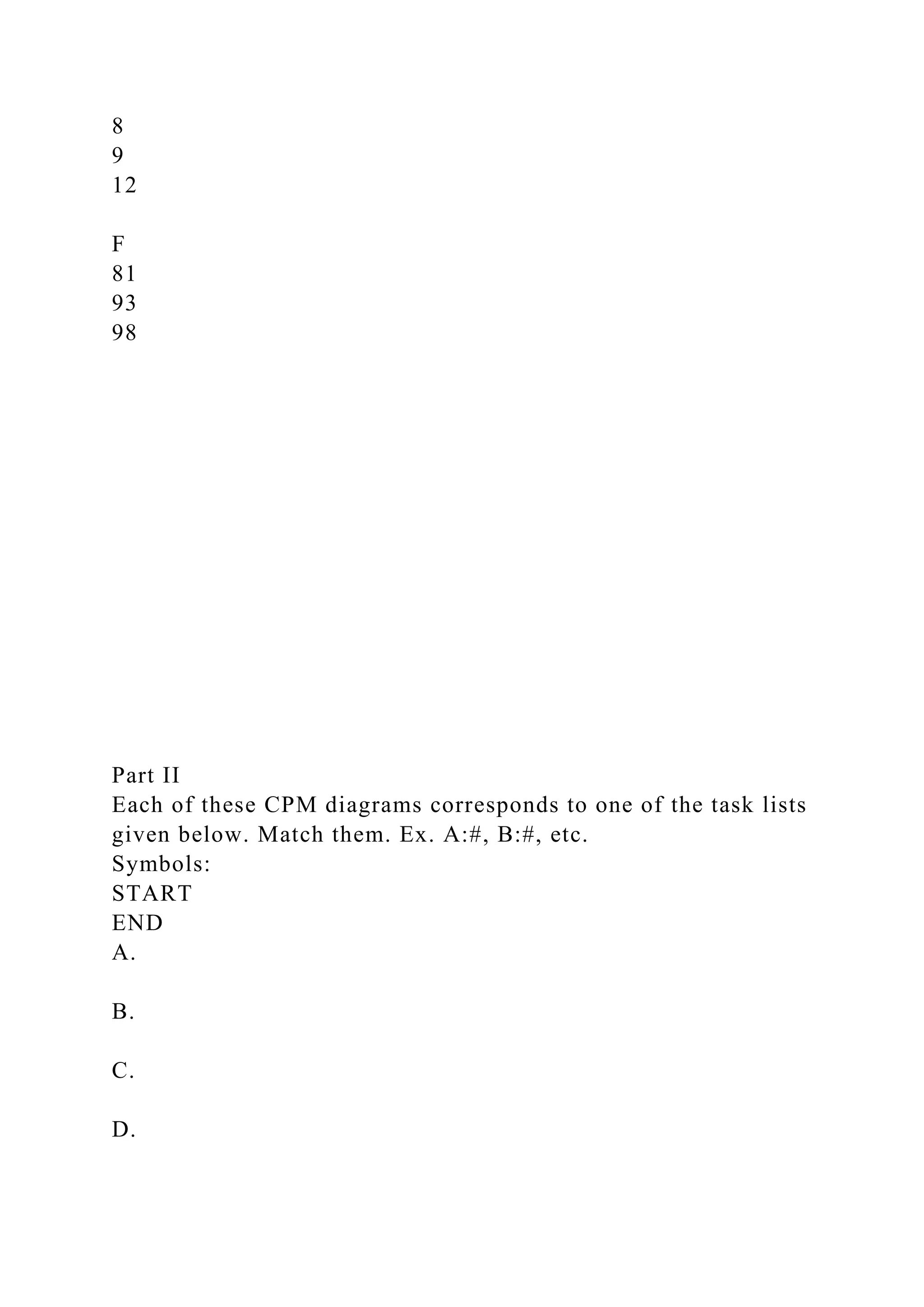

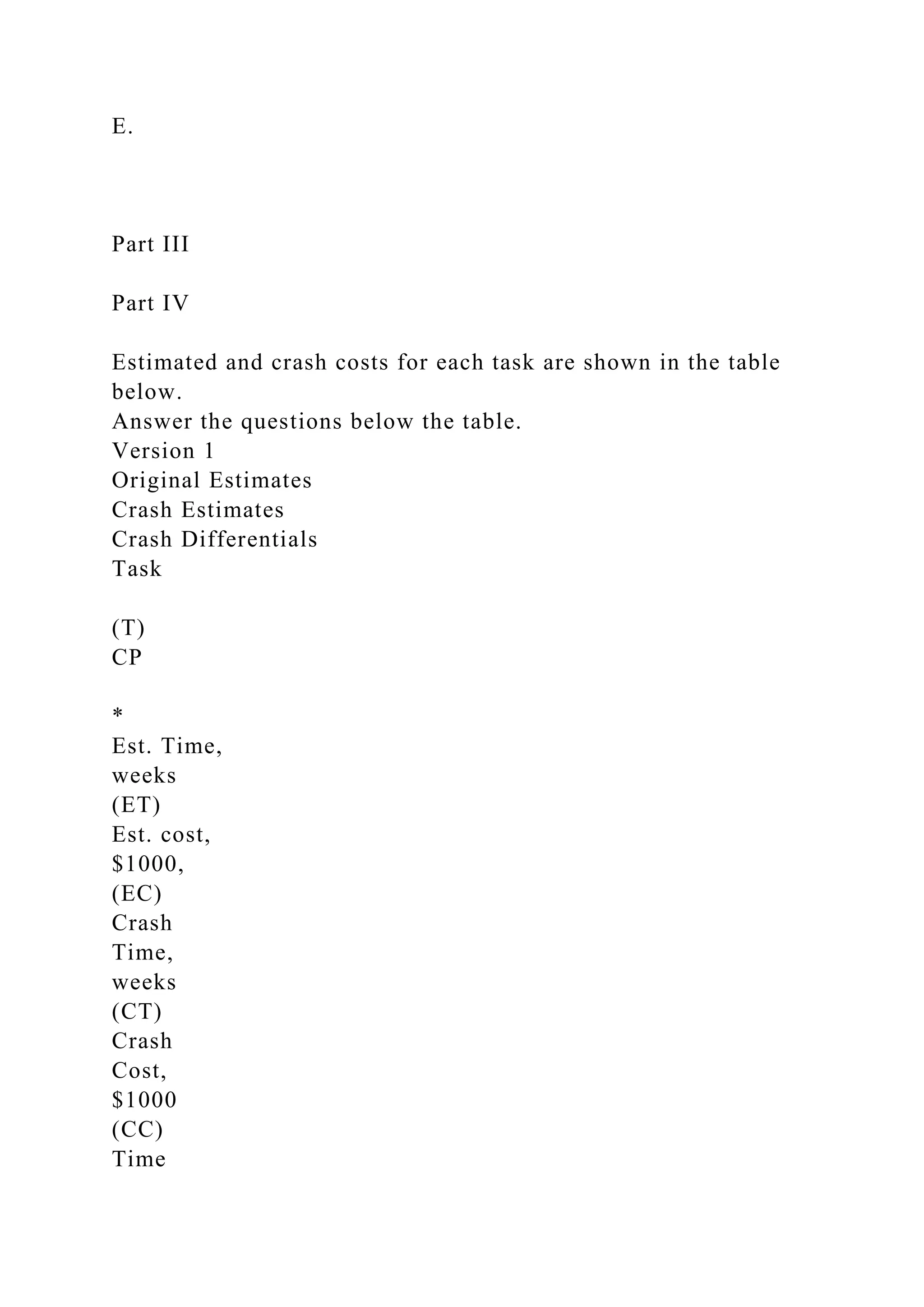

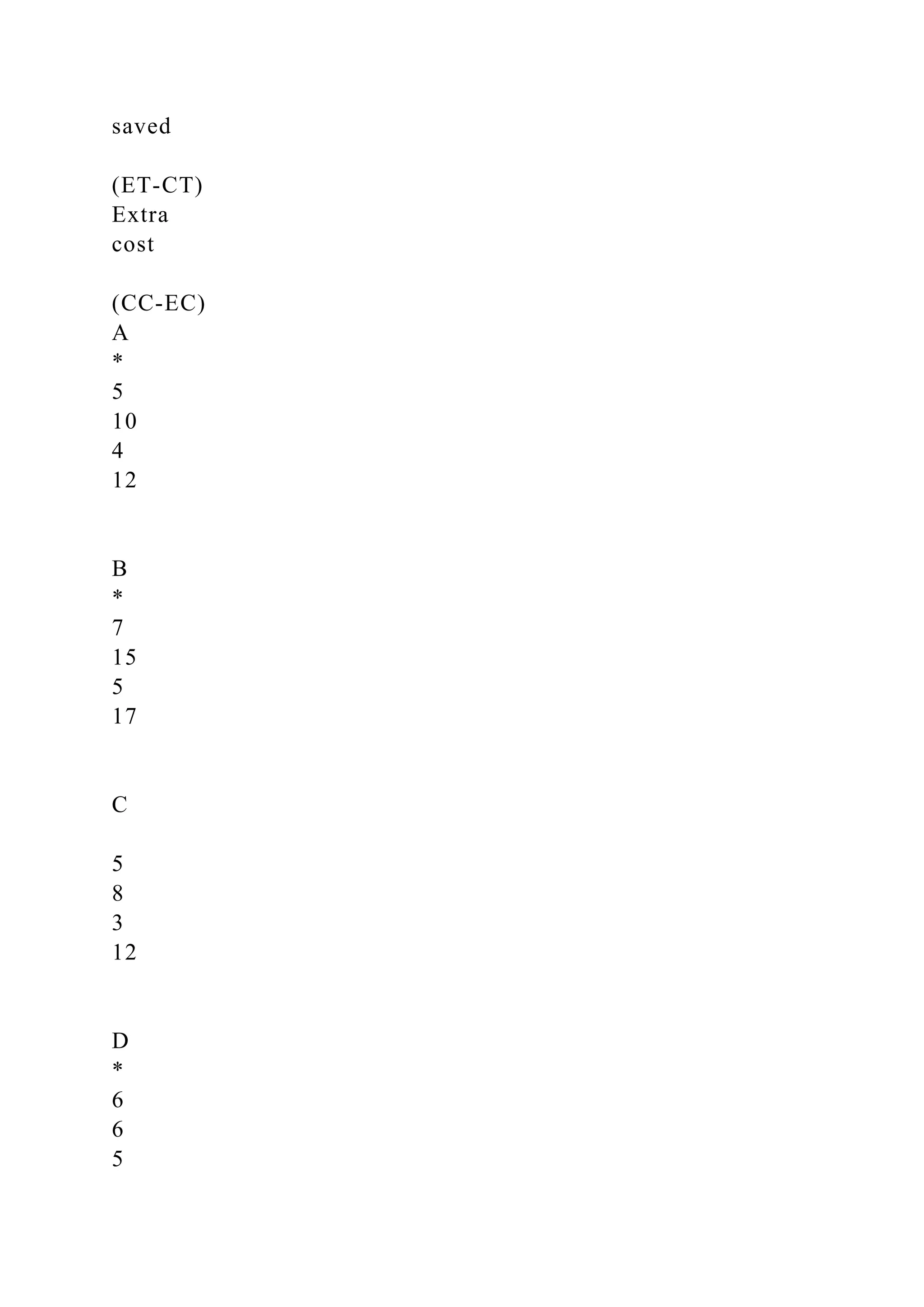

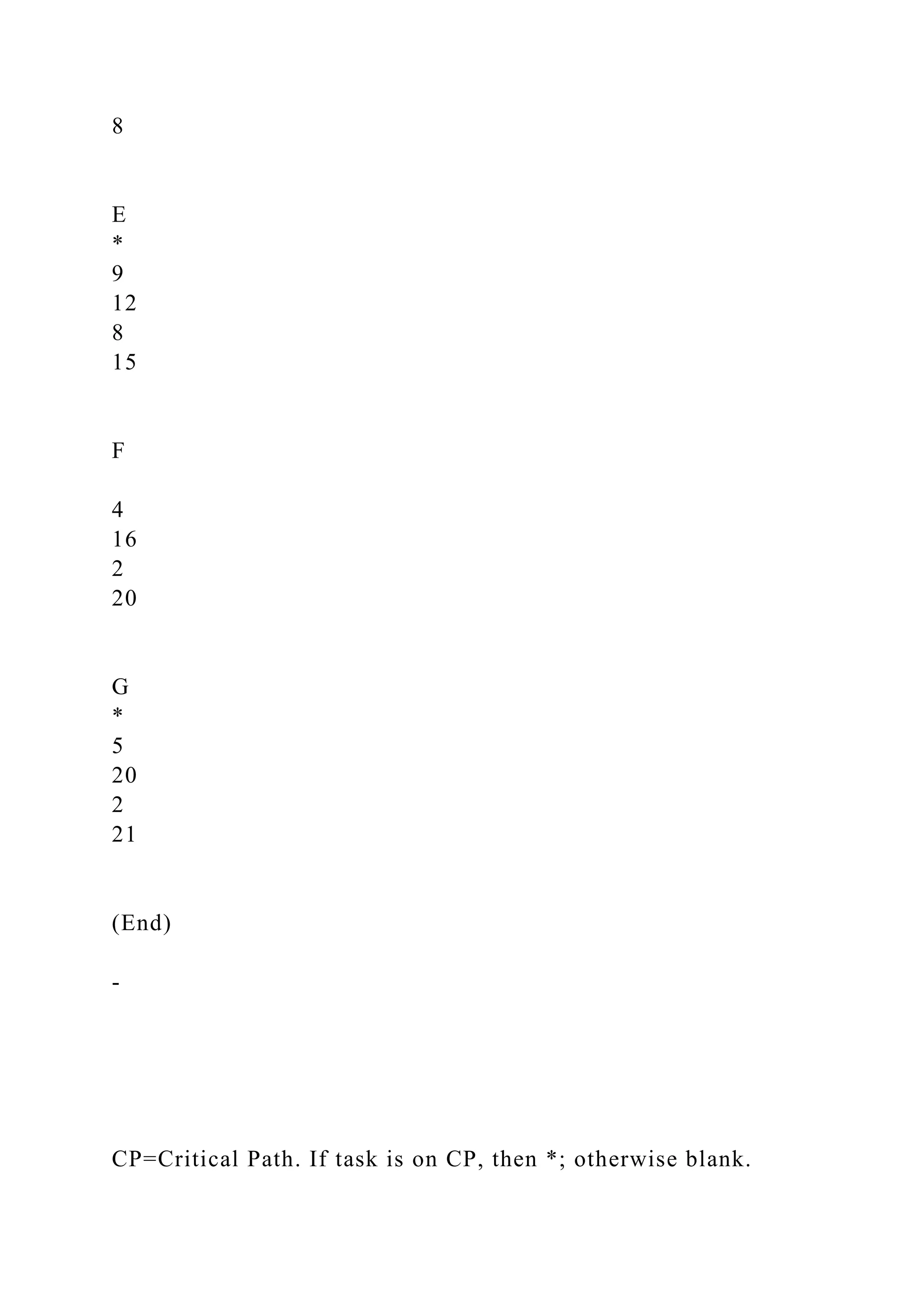

This document provides an overview of the Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) and the Critical Path Method (CPM), highlighting their roles in project management for estimating task duration and analyzing interdependent tasks. It explains how PERT generates an expected completion time using optimistic, pessimistic, and most likely estimates, while CPM identifies the critical path that dictates project duration based on task sequences. Practical examples are given to illustrate the application of both techniques in real-world project scenarios and decision-making processes regarding time management and cost efficiency.