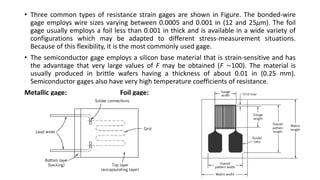

This document discusses stress and strain analysis through experimental measurement of material deformation. It focuses on strain measurement techniques, including the electrical resistance strain gage. The resistance strain gage works by measuring changes in electrical resistance caused by mechanical deformation. Its operation relies on the gage factor, which relates resistance change to strain. Proper installation of resistance strain gages requires a clean surface, suitable adhesive, and sufficient drying time.