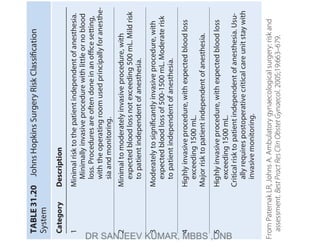

The document describes the Johns Hopkins Surgery Risk Classification System which categorizes surgical procedures into 5 categories based on invasiveness and risk to the patient independent of anesthesia. Category 1 procedures have minimal risk and invasiveness while Category 5 procedures have critical risk and invasiveness, usually requiring post-operative intensive care. It provides descriptions of the expected blood loss, risk level, and typical post-operative care for each category.

![35

•

Neuromuscular

Disorders

Including

Malignant

Hyperthermia

and

Other

Genetic

Disorders

1123

Diagnosis

in

the

Operating

Room

and

Postanesthesia

Care

Unit

As

stated

earlier,

fulminant

MH

is

rare,

and

early

signs

of

clini-

cal

MH

may

be

subtle

(Box

35.1).

These

signs

must

be

distin-

guished

from

other

disorders

with

similar

signs

(Box

35.2).

When

the

diagnosis

is

obvious

(i.e.,

fulminant

MH

or

suc-

cinylcholine-induced

rigidity

with

rapid

metabolic

changes),

marked

hypermetabolism

and

heat

production

occur,

and

there

may

be

little

time

left

for

specific

therapy

to

prevent

death

or

irreversible

morbidity.

If

the

syndrome

begins

with

slowly

increasing

end-tidal

CO

2

(defined

earlier),

specific

ther-

apy

can

await

a

complete

clinical

workup

before

treatment.

In

general,

MH

is

not

expected

to

occur

when

no

triggers

are

administered

(see

“Anesthesia

for

Susceptible

Patients”).

However,

several

confirmed

fulminant

nonanesthetic

cases

of

MH

that

resulted

in

death

have

been

reported

(see

“Non-

anesthetic

Malignant

Hyperthermia”).

148

When

volatile

anesthetics

or

succinylcholine

are

used,

MH

should

be

suspected

whenever

there

is

an

unexpected

increase

in

end-tidal

CO

2

(ETCO

2

),

undue

tachycardia,

tachypnea,

arrhythmias,

mottling

of

the

skin,

cyanosis,

muscle

rigidity,

sweating,

increased

body

temperature,

or

unstable

blood

pressure.

If

any

of

these

occur,

signs

of

increased

metabolism,

acidosis,

or

hyperkalemia

must

be

sought.

The

most

common

cause

for

sudden

ETCO

2

dur-

ing

general

anesthesia

and

sedation

is

hypoventilation.

Increased

minute

ventilation

should

be

able

to

correct

such

a

problem.

The

diagnosis

of

MH

can

be

supported

by

the

analysis

of

arterial

or

venous

blood

gases

which

demonstrates

a

mixed

respiratory

and

metabolic

acidosis;

184

however,

the

respi-

ratory

component

of

acidosis

may

be

predominate

in

the

very

early

stage

of

the

onset

of

fulminant

MH.

O

2

and

CO

2

change

more

markedly

in

the

central

venous

compartment

than

in

arterial

blood;

therefore

end-expired

or

venous

CO

2

levels

more

accurately

reflect

whole-body

stores.

Venous

CO

2

,

unless

the

blood

drains

an

area

of

increased

metabolic

activity,

should

have

PCO

2

levels

of

only

about

5

mm

Hg

greater

than

that

of

expected

or

measured

PaCO

2

.

In

small

children,

particularly

those

without

oral

food

or

fluid

for

a

prolonged

period,

the

base

deficit

may

be

5

mEq/L

because

of

their

smaller

energy

stores.

Any

patient

suspected

of

having

an

MH

episode

should

be

reported

to

the

North

American

MH

Registry

via

the

adverse

metabolic/muscular

reaction

to

anesthesia

(AMRA)

report

available

from

the

website

at

http://anest.ufl.edu/namhr/

namhr-report-forms/.

TREATMENT

Acute

management

for

MH

can

be

summarized

as

follows:

1.

Discontinue

all

triggering

anesthetics,

maintain

intrave-

nous

agents,

such

as

sedatives,

opioids,

and

nondepolar-

izing

muscular

blockers

as

needed,

and

hyperventilate

with

100%

oxygen

with

a

fresh

flow

to

at

least

10

L/min.

With

increased

aerobic

metabolism,

normal

ventilation

must

increase.

However,

CO

2

production

is

also

increased

because

of

neutralization

of

fixed

acid

by

bicarbonate;

hyperventilation

removes

this

additional

CO

2

.

2.

Administer

dantrolene

rapidly

(2.5

mg/kg

intrave-

nously

[IV]

to

a

total

dose

of

10

mg/kg

IV)

every

5

to

10

minutes

until

the

initial

symptoms

subside.

Early

Signs

Elevated

end-tidal

CO

2

Tachypnea

and/or

tachycardia

Masseter

spasm

if

succinylcholine

has

been

used

Generalized

muscle

rigidity

Mixed

metabolic

and

respiratory

acidosis

Profuse

sweating

Mottling

of

skin

Cardiac

arrhythmias

Unstable

blood

pressure

Late

Signs

Hyperkalemia

Rapid

increase

of

core

body

temperature

Elevated

creatine

phosphokinase

levels

Gross

myoglobinemia

and

myoglobinuria

Cardiac

arrest

Disseminated

intravascular

coagulation

BOX

35.1

Clinical

Signs

of

Malignant

Hyperthermia

Anaphylactic

reaction

Alcohol

therapy

for

limb

arteriovenous

malformation

Contrast

dye

injection

Cystinosis

Diabetic

coma

Drug

toxicity

or

abuse

Elevated

end-tidal

CO

2

due

to

laparoscopic

operation

Environmental

heat

gain

more

than

loss

Equipment

malfunction

with

increased

carbon

dioxide

Exercise

hyperthermia

Freeman-Sheldon

syndrome

Generalized

muscle

rigidity

Heat

stroke

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperkalemia

Hypokalemic

periodic

paralysis

Hypoventilation

or

low

fresh

gas

flow

Increased

ETCO

2

from

laparoscopic

surgery

Insufficient

anesthesia

and/or

analgesia

Malignant

neuroleptic

syndrome

Muscular

dystrophies

(Duchenne

and

Becker)

Myoglobinuria

Myotonias

Osteogenesis

imperfecta

Pheochromocytoma

Prader-Willi

syndrome

Recreational

drugs

Rhabdomyolysis

Sepsis

Serotonin

syndrome

Stroke

Thyroid

crisis

Ventilation

problems

Wolf-Hirschhorn

syndrome

BOX

35.2

Conditions

and

Disorders

that

May

Mimic

Malignant

Hyperthermia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-7-320.jpg)

![SECTION

III

•

Anesthesia

Management

1124

3.

Administer

bicarbonate

(1-4

mEq/kg

IV)

to

correct

the

metabolic

acidosis

with

frequent

monitoring

of

blood

gases

and

pH.

4.

Control

fever

by

administering

iced

fluids,

cooling

the

body

surface,

cooling

body

cavities

with

sterile

iced

fluids,

and

if

necessary,

using

a

heat

exchanger

with

a

pump

oxygenator.

Cooling

should

be

halted

at

38°C

to

prevent

inadvertent

hypothermia.

5.

Monitor

and

treat

arrhythmia.

Advanced

cardiac

life

support

protocol

may

be

applied.

6.

Monitor

and

maintain

urinary

output

to

greater

than

1

to

2

mL/kg/h

and

establish

diuresis

if

urine

output

is

inad-

equate.

Administer

bicarbonate

to

alkalinize

urine

to

pro-

tect

the

kidney

from

myoglobinuria-induced

renal

failure.

7.

Further

therapy

is

guided

by

blood

gases,

electrolytes,

CK,

temperature,

muscle

tone,

and

urinary

output.

Hyperkalemia

should

be

treated

with

bicarbonate,

glu-

cose,

and

insulin,

typically

10

units

of

regular

insulin

and

50

mL

of

50%

dextrose

for

adult

patients.

The

most

effective

way

to

lower

serum

potassium

is

reversal

of

MH

by

effective

doses

(ED)

of

dantrolene.

In

severe

cases,

cal-

cium

chloride

or

calcium

gluconate

may

be

used.

8.

Recent

data

demonstrated

that

magnesium

level

could

be

a

prerequisite

for

dantrolene

efficacy

in

managing

MH

crisis.

9.

Analyze

coagulation

studies

(e.g.,

international

nor-

malized

ratio

[INR],

platelet

count,

prothrombin

time,

fibrinogen,

fibrin

split,

or

degradation

products).

10.

Once

the

initial

reaction

is

controlled,

continued

moni-

toring

in

the

intensive

care

unit

for

24

to

48

hours

is

usually

recommended.

Adequate

personnel

support

is

critical

to

the

successful

management

of

such

a

crisis.

Discontinuation

of

the

trig-

ger

may

be

adequate

therapy

for

acute

MH

if

the

onset

is

slow

or

if

exposure

was

brief.

Changing

the

breathing

cir-

cuit

and

CO

2

absorbent

can

be

time-consuming.

However,

application

of

activated

charcoal

filters

may

rapidly

reduce

the

volatile

anesthetic

concentration

to

an

acceptable

level

in

less

than2

minutes,

if

they

are

readily

available.

185

Dantrolene

used

to

be

packaged

in

20-mg

bottles

with

sodium

hydroxide

for

a

pH

of

9.5

(otherwise

it

will

not

dis-

solve)

and

with

3

g

of

mannitol

(converts

the

hypotonic

solution

to

isotonic).

The

initial

dose

should

be

2.5

mg/

kg

dantrolene

reconstituted

in

sterile

water

and

adminis-

tered

intravenously.

Dantrolene

must

be

reconstituted

in

sterile

water

rather

than

salt

solutions

or

it

will

precipi-

tate.

It

has

been

shown

that

prewarming

of

sterile

water

may

expedite

the

solubilization

of

dantrolene

compared

to

water

in

ambient

temperature.

186

In

2009,

a

newer,

rapid

soluble

lyophilized

powder

form

of

dantrolene

became

available

for

intravenous

use.

It

reconstitutes

in

less

than

a

minute

which

is

much

faster

than

the

older

version.

187

The

higher

dosing

capacity,

250

mg

per

vial,

of

the

newer

version

of

dantrolene

also

reduces

the

stor-

age

space

with

a

similar

recommended

shelf

life

as

the

older

versions.

In

awake,

healthy

volunteers,

the

maximum

twitch

depression

occurs

at

a

dantrolene

dose

of

2.4

mg/kg.

188

Therefore

it

is

not

surprising

that

at

therapeutic

concen-

trations,

dantrolene

may

prolong

the

need

for

intubation

and

assisted

ventilation.

Brandom

and

associates

reviewed

the

complications

associated

with

the

administration

of

dantrolene

from

1987

to

2006

using

the

dataset

in

the

NAMHR

via

the

AMRA

reports

and

found

that

the

most

frequent

complications

of

dantrolene

were

muscle

weak-

ness

(21.7%),

phlebitis

(9%),

gastrointestinal

upset

(4.1%),

respiratory

failure

(3.8%),

hyperkalemia

(3.3%),

and

exces-

sive

secretions

(8.2%).

189

Given

its

high

pH,

it

is

advisable

to

administer

dantrolene

through

a

large

bore

IV

line.

It

has

been

demonstrated

that

dantrolene

interferes

with

EC

coupling

of

murine

intestinal

smooth

muscle

cells,

190

rat

gastric

fundus,

and

colon,

191

which

in

part

explains

its

gastrointestinal

side

effect.

Caution

should

be

used

when

ondansetron

is

to

be

used

in

this

setting.

As

a

serotonin

antagonist,

ondansetron

may

increase

serotonin

at

the

5-HT

2A

receptor

in

the

presynaptic

space.

In

MHS

individu-

als,

agonism

of

5-HT

2A

receptor

may

produce

a

deranged

response,

precipitating

MH.

192

The

clinical

course

will

determine

further

therapy

and

studies.

Dantrolene

should

probably

be

repeated

at

least

every

10

to

15

hours,

since

it

has

a

half-life

of

at

least

10

hours

in

children

and

adults.

188,193

The

total

dose

of

dan-

trolene

that

can

be

used

is

up

to

30

mg/kg

in

some

cases.

Recrudescence

of

MH

can

approach

50%,

usually

within

6.5

hours.

194,195

When

indicated,

calcium

and

cardiac

glycosides

may

be

used

safely.

They

can

be

lifesaving

dur-

ing

persistent

hyperkalemia.

Slow

voltage-gated

calcium

channel

blockers

do

not

increase

porcine

survival.

196,197

Instead,

a

recent

study

by

Migita

demonstrated

that

cal-

cium

channel

blockers,

including

dihydropyridine

(i.e.,

nifedipine),

phenylalkylamine

(i.e.,

verapamil),

and

ben-

zothiazepine

(i.e.,

diltiazem),

led

to

increased

[Ca

2+

]

i

in

human

skeletal

muscle

cells.

Interestingly,

the

potency

of

such

calcium

release

is

correlated

with

the

number

of

binding

sites

on

DHPR

(i.e.,

nifedipine

>

verapamil

>

dil-

tiazem).

198

Clinical

doses

of

dantrolene

were

only

able

to

attenuate

20%

of

the

nifedipine-induced

[Ca

2+

]

i

surge.

198

Current

recommendations

of

MHAUS

discourage

the

use

of

calcium

channel

blockers

in

the

presence

of

dantrolene

because

they

can

worsen

the

hyperkalemia

resulting

in

cardiac

arrest.

Although

administration

of

magnesium

sulfate

could

not

prevent

the

development

of

MH

and

did

not

influence

the

clinical

course

in

succinylcholine-

induced

MH,

199

recent

data

suggested

that

dantrolene

might

require

magnesium

to

arrest

the

course

of

MH

trig-

gered

by

halothane.

200

Permanent

neurologic

sequelae,

such

as

coma

or

paralysis,

may

occur

in

advanced

cases,

probably

because

of

inadequate

cerebral

oxygenation

and

perfusion

for

the

increased

metabolism

and

because

of

the

fever,

acidosis,

hypo-osmolality

with

fluid

shifts,

and

potassium

release.

For

MH

cases

diagnosed

in

the

ambulatory

surgical

cen-

ters,

guidelines

have

been

recently

proposed

for

the

trans-

ferring

of

care

to

receiving

hospital

facilities.

201

Although

it

is

preferable

that

immediate

treatment

and

stabilization

of

the

patient

be

achieved

onsite,

several

factors

need

to

be

considered

before

implementation

of

a

transfer

plan,

which

include

capabilities

of

the

available

professionals

at

the

initial

treatment

and

receiving

facilities,

clinical

best

interests

of

patients,

and

capabilities

of

the

transfer

team.

202

The

validity

of

stocking

dantrolene

in

ambula-

tory

surgery

centers

was

confirmed

with

a

cost-effective-

ness

analysis.

203](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-8-320.jpg)

![SECTION

III

Anesthesia

Management

1302

Co-oximetry

is

considered

the

gold

standard

for

S

a

O

2

mea-

surements

and

is

relied

on

in

circumstances

when

pulse

oximetry

readings

are

inaccurate

or

unobtainable.

Pulse

Oximetry

Standard

pulse

oximetry

aims

to

provide

a

noninvasive,

in vivo,

and

continuous

assessment

of

functional

S

a

O

2

.

Esti-

mates

of

S

a

O

2

based

on

pulse

oximetry

are

denoted

as

S

p

O

2

.

The

history

of

the

development

of

the

pulse

oximetry

has

been

reviewed

in

detail

elsewhere.

14

Pulse

oximetry

takes

advantage

of

the

pulsatility

of

arte-

rial

blood

flow

to

provide

an

estimate

of

S

a

O

2

by

differentiat-

ing

light

absorption

by

arterial

blood

from

light

absorption

by

other

components.

When

compared

with

in vitro

oximetry

of

an

arterial

blood

sample,

the

challenge

of

obtaining

arterial

O

2

saturation

in vivo

is

to

ensure

that

the

light

is

sampling

arterial

blood

and

to

account

for

its

absorption

by

other

tis-

sues.

As

illustrated

in

Fig.

41.4,

light

absorption

by

tissue

can

be

divided

into

a

time-varying

(pulsatile)

component,

histori-

cally

referred

to

as

“AC”

(from

“alternating

current”),

and

a

steady

(nonpulsatile)

component,

referred

to

as

“DC”

(“direct

current”).

In

conventional

pulse

oximetry,

the

ratio

(R)

of

AC

and

DC

light

absorption

at

two

different

wavelengths

is

calcu-

lated.

The

wavelengths

of

light

are

selected

to

maximize

the

difference

between

the

ratios

of

the

absorbances

of

O

2

Hb

and

deO

2

Hb

(see

Fig.

41.3B).

The

most

commonly

used

wave-

lengths

of

light

are

660

nm

and

940

nm.

At

660

nm,

there

is

greater

light

absorption

by

deO

2

Hb

than

by

O

2

Hb.

At

940

nm,

there

is

greater

light

absorption

by

O

2

Hb

than

by

deO

2

Hb,

(41.5)

where

AC

660

,

AC

940

,

DC

660

,

and

DC

940

denote

the

corre-

sponding

AC

and

DC

components

of

the

640-nm

and

940-

nm

wavelengths.

The

ratio

R

is

then

empirically

related

to

O

2

saturation

based

on

a

calibration

curve

internal

to

each

pulse

oximeter

(Fig.

41.5).

13

Each

manufacturer

develops

its

own

calibration

curve

by

having

volunteers

breathe

hypoxic

gas

mixtures

to

create

a

range

of

S

a

O

2

values

between

70%

and

100%.

The

FDA

0

5

10

15

20

25

650

600

550

500

700

nm

Methemoglobin

Oxyhemoglobin

Reduced

hemoglobin

Carboxyhemoglobin

Sulfhemoglobin

0.01

10

1

0.1

920

960

600

640

680

720

Wavelength

(nm)

760

800

840

880

Extinction

coefficient

Red

Infrared

Methemoglobin

Oxyhemoglobin

Reduced

hemoglobin

Carboxyhemoglobin

A

B

Wavelength

(nm)

Millimolar

absorptivity

Fig.

41.3

(A)

Absorption

spectra

of

five

species

of

hemoglobin

for

wavelengths

of

light

across

the

visible

spectrum.

(B)

Extinction

coefficients

of

the

most

frequently

measured

hemoglobin

species

extending

to

infrared

wavelengths

used

for

pulse

oximetry.

The

vertical

lines

indicate

specific

wave-

lengths

for

red

and

infrared

light

applied

in

pulse

oximeters.

The

differences

in

the

extinction

coefficients

of

oxyhemoglobin

and

reduced

hemoglobin

(deoxygenated

hemoglobin)

are

pronounced

at

these

wavelengths.

Note

that

the

extinction

coefficients

of

carboxyhemoglobin

and

methemoglobin

are

similar

to

those

of

oxyhemoglobin

and

reduced

hemoglobin,

respectively,

at

660

nm.

([A]

Redrawn

from

Zwart

A,

van

Kampen

EJ,

Zijlstram

WG.

Results

of

routine

determination

of

clinically

significant

hemoglobin

derivatives

by

multicompartment

analysis.

Clin

Chem.

1986;32:972–978.

[B]

Modified

from

Trem-

per

KK,

Barker

SJ.

Pulse

oximetry.

Anesthesiology.

1989;70:98–108.)

AC

Absorption

from

pulsatile

arterial

blood

Absorption

from

nonpulsatile

arterial

blood

Absorption

from

venous

and

capillary

blood

Absorption

from

tissue

DC

Time

Light

absorption

Fig.

41.4

Schematic

of

the

Pulse

Principle.

Absorption

of

light

passing

through

tissue

is

characterized

by

a

pulsatile

component

(AC)

and

a

nonpul-

satile

component

(DC).

The

pulsatile

component

of

absorption

is

due

to

arterial

blood.

The

nonpulsatile

component

is

due

to

venous

blood

and

the

remainder

of

the

tissues.

(Redrawn

from

Severinghaus

JW.

Nomenclature

of

oxygen

saturation.

Adv

Exp

Med

Biol.

1994;345:921–923)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-28-320.jpg)

![Respiratory

Monitoring

1313

˙

˙

mismatch

is

the

most

common

cause

of

hypoxemia

in

the

clinical

setting.

Ventilation

and

perfusion

are

non-

uniformly

distributed

throughout

the

normal

lung,

with

worsening

mismatch

in

the

setting

of

lung

disease,

general

anesthesia,

and

mechanical

ventilation.

Areas

with

low

or

zero

˙

˙

yield

low

end-capillary

PO

2

,

whereas

areas

with

normal

or

high

˙

˙

produce

higher

end-capillary

PO

2

.

However,

because

of

the

plateau

of

the

O

2

Hb

dissociation

curve

(see

Fig.

41.2),

the

normal

and

high

˙

˙

regions

are

limited

in

the

extent

to

which

they

increase

the

O

2

content

and

compensate

for

the

low

˙

˙

regions

(Fig.

41.15).

Con-

sequently,

˙

˙

mismatch

results

in

hypoxemia.

Right-to

left

shunt

is

the

amount

of

blood

that

flows

from

the

pulmonary

artery

to

the

systemic

arterial

circulation

without

undergoing

pulmonary

gas

exchange.

It

represents

an

extreme

case

of

˙

˙

mismatch

in

which

the

ratio

equals

zero

and

the

end-capillary

gas

partial

pressures

are

equal

to

the

values

found

in

mixed

venous

blood.

In

healthy

awake

spontaneously

breathing

subjects,

intrapulmonary

shunt

is

negligible,

179

and

a

small

(<1%

of

cardiac

output)

extrapul-

monary

shunt

results

from

drainage

of

the

bronchial

and

Thebesian

veins

into

the

arterial

side

of

the

circulation.

180

During

general

anesthesia,

a

right-to-left

shunt

can

develop

as

a

result

of

atelectasis.

181,182

Right-to-left

shunt

can

also

be

seen

in

pathologic

conditions

such

as

pneumonia

and

acute

lung

injury.

The

effect

of

the

shunt

on

P

a

O

2

is

a

func-

tion

of

the

magnitude

of

the

shunt,

F

I

O

2

,

and

the

cardiac

output

(Fig.

41.16).

Importantly,

increases

in

F

I

O

2

have

a

small

effect

on

P

a

O

2

in

the

presence

of

large

true

right-to-left

shunt

(see

Fig.

41.16).

The

traditional

method

to

estimate

flow

through

shunt-

ing

regions

(

˙

)

as

a

fraction

of

the

total

cardiac

output

(

˙

)

is

based

on

the

modeling

of

the

lung

as

a

three-compartment

system

(Fig.

41.17).

183

The

three

compartments

represent

(1)

lung

regions

receiving

both

ventilation

and

perfusion,

TABLE

41.2

Causes

of

Changes

in

Partial

Pressure

of

End-Tidal

Carbon

Dioxide

↑P

ET

CO

2

↓P

ET

CO

2

↑CO

2

Production

and

Delivery

to

the

Lungs

Increased

metabolic

rate

Fever

Sepsis

Seizures

Malignant

hyperthermia

Thyrotoxicosis

Increased

cardiac

output

(e.g.,

during

CPR)

Bicarbonate

administration

↓CO

2

Production

and

Delivery

to

the

Lungs

Hypothermia

Pulmonary

hypoperfusion

Cardiac

arrest

Pulmonary

embolism

Hemorrhage

Hypotension

↓Alveolar

Ventilation

Hypoventilation

Respiratory

center

depression

Partial

muscular

paralysis

Neuromuscular

disease

High

spinal

anesthesia

COPD

↑Alveolar

Ventilation

Hyperventilation

Equipment

Malfunction

Rebreathing

Exhausted

CO

2

absorber

Leak

in

ventilator

circuit

Faulty

inspiratory/expiratory

valve

Equipment

Malfunction

Ventilator

disconnect

Esophageal

intubation

Complete

airway

obstruction

Poor

sampling

Leak

around

endotracheal

tube

cuff

CO

2

,

Carbon

dioxide;

COPD,

chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease;

CPR,

cardiopulmonary

resuscitation;

P

ET

CO

2

,

partial

pressure

of

end-tidal

carbon

dioxide.

Modified

from

Hess

D.

Capnometry

and

capnography:

technical

aspects,

physiologic

aspects,

and

clinical

applications.

Respir

Care.

1990;35:557–576.

Increased

ventilation-perfusion

heterogeneity,

particularly

with

high

V/Q

regions

Pulmonary

hypoperfusion

Pulmonary

embolism

Cardiac

arrest

Positive

pressure

ventilation

(especially

with

PEEP)

High-rate

low-tidal-volume

ventilation

BOX

41.2

Causes

of

Increased

Arterial-

to-End-Tidal

Carbon

Dioxide

Pressure

Difference

P

(a-ET)CO2

PEEP,

Positive

end-expiratory

pressure.

Modified

from

Hess

D.

Capnom-

etry

and

capnography:

technical

aspects,

physiologic

aspects,

and

clinical

applications.

Respir

Care.

1990;35:557–576.

Expired

volume

Z

Y

X

q

p

F

CO

2

F

ET

CO

2

F

CO

2

of

a

gas

in

equilibrium

with

arterial

blood

V

D

aw

V

T

alv

V

T

Fig.

41.13

The

volume

capnogram

is

a

plot

of

the

fraction

of

CO

2

(FCO

2

)

in

exhaled

gas

versus

exhaled

volume.

It

is

divided

into

three

phases,

which

reflect

the

same

sources

of

expired

gas

as

present

in

the

time

capnograph:

anatomic

dead

space

(phase

I,

red),

transitional

(phase

II,

blue),

and

alveolar

gas

(phase

III,

green).

The

volume

capno-

gram

allows

for

the

partition

of

total

tidal

volume

(V

T

)

into

airway

dead

space

volume

(V

D

aw)

and

an

effective

alveolar

tidal

volume

(V

T

alv)

by

a

vertical

line

through

Phase

II,

positioned

such

that

the

approximately

triangular

areas

p

and

q

are

equal.

It

also

provides

the

slope

of

phase

III

as

a

quantitative

measure

of

the

heterogeneity

of

alveolar

ventila-

tion.

The

total

area

below

the

horizontal

line

(denoting

the

FCO

2

of

a

gas

in

equilibrium

with

arterial

blood)

can

be

divided

into

three

dis-

tinct

areas:

X,

Y,

and

Z.

Area

X

corresponds

to

the

total

volume

of

CO

2

exhaled

over

a

tidal

breath.

This

value

can

be

used

to

compute

the

CO

2

production

(

V

CO

2

),

and

the

mixed

expired

CO

2

fraction

or

partial

pres-

sure

to

be

used

in

the

Bohr

equation

(Eq.

[41.15])

based

on

the

divi-

sion

of

the

exhaled

CO

2

volume

by

the

exhaled

tidal

volume.

Area

Y

represents

wasted

ventilation

due

to

alveolar

dead

space,

while

area

Z

corresponds

to

wasted

ventilation

due

to

anatomic

deadspace

(V

D

aw).

Thus

areas

Y

+

Z

represent

the

total

physiologic

dead

space.

The

vol-

ume

capnogram

can

also

be

plotted

as

a

PCO

2

versus

exhaled

volume

curve.

F

ET

CO

2

,

Fraction

of

end-tidal

carbon

dioxide.

(Modified

from

Fletcher

R,

Jonson

B,

Cumming

G,

et

al.

The

concept

of

deadspace

with

special

reference

to

the

single

breath

test

for

carbon

dioxide.

Br

J

Anaesth.

1981;53:77–88.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-31-320.jpg)

![Neuromuscular

Monitoring

1371

Reversal

with

sugammadex

(SUG)

Reversal

with

neostigmine

(NEO)

PTC

0

PTC

1–15

TOF

0.9

No

response

to

TOF

TOF

ratio

1.0

Reversal

when

quantitative

(objective)

neuromuscular

monitoring

is

available

and

reliable

SUG

16

mg/kg

SUG

4

mg/kg

SUG

2

mg/kg

SUG

2

mg/kg

No

reversal

NEO

0.05

mg/kg

NEO

0.02

mg/kg

Delay

reversal

to

the

TOF

count

of

2

TOF

count

1–4

TOF

0.4

or

TOF

count

2–3

TOF

0.9

TOF

0.9

TOF

0.4–0.9

TOF

0–1

Reversal

with

sugammadex

(SUG)

Reversal

with

neostigmine

(NEO)

PTC

0

PTC

1–15

No

response

to

TOF

No

response

to

TOF

TOF

count

1–4

with

or

without

fade

Reversal

when

peripheral

(subjective)

nerve

stimulator

is

available

only

or

quantitative

neuromuscular

monitoring

is

unreliable

SUG

16

mg/kg

SUG

4

mg/kg

With

fade

Without

fade

NEO

0.04

mg/kg

NEO

0.02

mg/kg

SUG

2

mg/kg

NEO

0.05

mg/kg

Delay

reversal

to

the

TOF

count

of

2

TOF

count

4

TOF

count

2–3

Fig.

43.20

Suggestion

to

diminish

the

incidence

of

residual

curarization

by

neostigmine

(NEO)

or

sugammadex

(SUG)

according

to

the

level

of

block,

determined

with

a

nerve

stimulator

(quantitative

or

peripheral).

Note

that

only

a

quantitative

measured

TOF

ratio

of

0.90

to

1.00

ensures

low

risk

of

clinically

significant

residual

block.

PTC,

Posttetanic

count;

TOF,

train-of-four.

(Modified

from

Kopman

AF,

Eikermann

M.

Antagonism

of

non-depolarising

neuromuscular

block:

current

practice.

Anaesthesia.

2009;64[Suppl

1]:22–30.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-34-320.jpg)

![Respiratory

Disorders

Acute

Respiratory

Acidosis

Expected

[

HCO

−

3

]

=

24

+

[(

measured

PaCO

2

−

40

)

/10

]

Chronic

Respiratory

Acidosis

Expected

[

HCO

−

3

]

=

24

+

4

[(

measured

PaCO

2

−

40

)

/10

]

Acute

Respiratory

Alkalosis

Expected

[

HCO

−

3

]

=

24

−

2

[(

40

−

measured

PaCO

2

)

/10

]

Chronic

Respiratory

Alkalosis

Expected

[

HCO

−

3

]

=

24

−

5

[(

40

−

measured

PaCO

2

)

/10

]

(

range:

±

Metabolic

Disorders

Metabolic

Acidosis

Expected

PaCO

2

=

1

.

5

×

[

HCO

−

3

]

+

8

(

range

:

±

2

)

Metabolic

Alkalosis

Expected

PaCO

2

=

0

.

7

[

HCO

−

3

]

+

20

(

range

:

±

5

)

BOX

48.1

The

Descriptive

(CO

2

−HCO

3

−

)

Approach

to

Acid-Base](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-52-320.jpg)

![THE

SEMI-QUANTITATIVE

(BASE

DEFICIT/

EXCESS

[COPENHAGEN])

APPROACH

In

metabolic

acidosis,

the

addition

of

UMA

to

the

ECF

results

in

a

net

gain

of

one

hydrogen

ion

for

each

anion.

This

is

buffered,

principally

by

bicarbonate,

such

that

each

anion

gained

results

in

an

equivalent

fall

in

the

bicarbonate

con-

centration.

Thus,

the

change

in

the

bicarbonate

concentra-

tion

from

baseline

should

reflect

the

total

quantity

of

net

Delta

ratio

=

ΔAnion

gap/Δ

[

HCO

−

3

]

or

↑

anion

gap/

↓

[

HCO

−

3

]

=

Measured

anion

gap–

Normal

anion

gap

Normal

[

HCO

−

3

]

–

Measured

[

HCO

−

3

]

=

(

AG

–

12

)

(

24

−

[

HCO

−

3

])

BOX

48.2

The

Delta

Anion

Gap

(Delta

Ratio)

Acidosis

<7.35

Anion

gap

Delta

ratio

Correct

for

albumin

Acute

Chronic

Alkalosis

>7.45

pH

Delta

ratio

Clinical

assessment

<0.4

<1

1

to

2

>2

Hyperchloremic

normal

AG

acidosis

High

AG

and

normal

AG

acidosis

Pure

anion

gap

acidosis

Lactic

acidosis:

average

value

1.6

DKA

more

likely

to

have

a

ratio

closer

to

1

because

of

urine

ketone

loss

High

AG

acidosis

and

concurrent

metabolic

alkalosis

or

preexisting

compensated

respiratory

acidosis

Metabolic

acidosis

Pa

CO

2

Pa

CO

2

Pa

CO

2

Pa

CO

2

=

Pa

CO

2

Respiratory

alkalosis

Pa

CO

2

Respiratory

acidosis

Pa

CO

2

Metabolic

alkalosis

Pa

CO

2

Fig.

48.4

The

Descriptive

(“Boston”)

Approach

to

Acid-Base

Balance.

DKA,

Diabetic

ketoacidosis;

AG,

Anion

gap.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-53-320.jpg)

![Perioperative

Acid-Base

Balance

1535

There

has

been

considerable

discussion

over

the

past

60

years

about

the

merits

and

demerits

of

the

BE,

as

compared

to

the

CO

2

-HCO

3

−

system.

In

reality,

there

is

little

difference

between

the

two;

both

equations

and

nomograms

were

derived

from

patient

data

and

abstracted

backward.

Cal-

culations

use

bicarbonate

as

measured

on

a

blood

gas

ana-

lyzer.

Consequently,

for

most

patients,

either

approach

is

relatively

accurate

but

may

be

misleading

because

they

do

not

allow

the

clinician

to

distinguish

between,

for

exam-

ple,

acidosis

due

to

lactate

or

chloride,

or

alkalosis

due

to

dehydration

or

hypoalbuminemia.

These

measures

may

miss

the

presence

of

an

acid-base

disturbance

entirely;

for

example,

a

hypoalbuminemic

(metabolic

alkalosis)

criti-

cally

ill

patient

with

a

lactic

acidosis

(metabolic

acidosis)

may

have

a

normal

range

pH,

bicarbonate,

and

BE.

This

lack

of

precision

may

lead

to

inappropriate

or

inadequate

therapy.

Changes

in

the

BE

occur

secondary

to

alterations

in

the

relative

concentrations

of

sodium,

chloride,

free

water,

albumin,

phosphate,

and

UMA.

By

calculating

the

contribution

of

the

individual

components

of

the

BE

it

is

possible

to

identify:

(1)

contraction

alkalosis,

(2)

hypo-

albuminemic

alkalosis,

(3)

hyperchloremic

acidosis,

(4)

dilution

acidosis

(if

indeed

it

exists),

and

(5)

acidosis

sec-

ondary

to

UMA.

This

approach,

which

can

be

labelled

the

base-deficit

gap,

has

been

proposed

by

Gilfix

and

Magder

(see

Box

48.3)

58

and

simplified

subsequently

by

Balasu-

bramanyan

and

associates

59

and

Story

and

associates.

60

The

BDG

should

mirror

the

SIG

(below)

the

corrected

AG.

The

simplified

calculation

as

proposed

by

Story

et al.

is

very

easy

to

calculate

at

the

bedside

and

in

the

majority

of

situations

(see

Box

48.3)

replicates

the

more

complex

calculations

originally

proposed

by

Gilfix

and

Magder.

58

STEWART

APPROACH

A

more

accurate

reflection

of

true

acid-base

status

can

be

derived

using

the

Stewart

or

physical

chemi-

cal

approach,

subsequently

updated

by

Fencl.

5,15

This

approach

is

based

on

the

concept

of

electrical

neutrality,

a

small

advance

from

the

AG.

There

exists,

in

plasma,

a

(

)

of

40

to

44

mEq/L,

balanced

by

the

negative

charge

on

bicar-

bonate

and

A

TOT

(the

BB—SIDe).

There

is

a

small

difference

between

SIDa

(apparent

SID)

and

BB

(SIDe—effective

SID)

that

represents

a

SIG

and

quantifies

the

amount

of

UMA

present

(Fig.

48.7).

(

)

[

]

[

]

[

]

(

)

[

]

[

]

[

]

(

)

Weak

acids’

degree

of

ionization

is

pH

dependent,

so

one

must

calculate

for

this:

[

]

[

]

(

.

)

Pi

(mmol/L)

=

[PO

4

]

×

(0.309

×

pH

–

0.469)

(

)

Unfortunately,

the

SIG

may

not

represent

unmeasured

strong

anions

but

only

all

anions

that

are

unmeasured.

For

example,

if

a

patient

has

been

resuscitated

with

gelatin,

his/

her

SIG

will

increase.

Further,

SID

changes

quantitatively

in

absolute

and

relative

terms

when

there

are

changes

in

plasma

water

concentration.

Fencl

has

addressed

this

by

correcting

the

chloride

concentration

for

free

water

(Cl

−

corr)

using

the

following

equation

5

:

[Cl

−

]

corr

=

[Cl

−

]

observed

×

([Na

+

]normal

/

[Na

+

]observed

).

This

corrected

chloride

concentration

may

then

be

inserted

into

the

SIDa

equation

above.

Similarly,

the

derived

value

for

UMA

can

also

be

corrected

for

free

water

by

sub-

stituting

UMA

for

Cl

−

in

the

above

equation.

25

In

a

series

of

nine

normal

subjects,

Fencl

estimated

the

“normal”

SIG

as

8

±

2

mEq/L.

25

Calculation

of

SIG

is

cumbersome.

The

data

required

are

more

extensive

and

thus

more

expensive

than

other

approaches

and

there

is

much

confusion

about

the

normal

range

of

SIG.

It

is

unclear,

in

standard

clinical

practice,

that

SIG

has

any

advantage

over

AGc

(which

is

SIG

without

cal-

cium,

magnesium,

and

phosphate—which

usually

cancel

out

each

other’s

charges).

In

all

likelihood

no

single

number

will

ever

allow

us

to

make

sense

of

complex

acid-base

disturbances.

Fencl

25

has

suggested

that,

rather

than

focusing

on

AG

or

BDE,

physicians

should

address

each

blood

gas

in

terms

of

all

alkalinizing

and

acidifying

effects:

respiratory

acidosis/

alkalosis,

the

presence

or

absence

of

abnormal

SID

(due

to

BE

NaW

(

water

and

sodium

effect

)

=

0.3

([

Na

+

meas

]

-140

)

mEq/L

BE

Cl

(

chloride

effect

)

=

102

−

[

Cl

−

effective

]

(

mEq/L

)

BE

Pi

(

phosphate

effect

)

=

(

0

.

309

×

(

pH

–

0

.

47

))

×

Pi

mEq/L

BE

prot

(

protein

effect

)

=

(

42

−

[

Albumin

g/L

])

*

(

0.148

×

pH

−

0.818

)

BE

calc

=

NE

NaW

+

BE

Cl

+

BE

PO4

+

BE

prot

BE

Gap

=

BE

calc

–

BE

actual

–

[

lactate

mEq/L

]

A

Simplified

Calculation

of

the

Base

Excess

Gap

60

BE

NaCl

=

([

Na

+

]

–

[

Cl

–

])

–

38

BE

Alb

=

0.25

(

42

–

albumin

g/L

)

BE

NaCl

–

BE

Alb

=

BDE

calc

BE

actual

–

BE

calc

–

[

lactate

]

=

BEG=

the

effect

of

unmeasured

anions

or

cations

BOX

48.3

Calculation

of

the

Base

Excess

Gap

12,58,59

*This

approach

involves

calculating

the

base

deficit

excess

for

sodium,

chloride,

and

free

water

(BE

NaCl

),

and

that

for

albumin

(BE

Alb

).

The

re-

sult

is

the

calculated

BE

(BE

calc

).

This

is

subtracted

from

the

measured

BE

to

find

the

BE

gap.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-55-320.jpg)

![□

Conventional

perioperative

analgesia

regimens

do

not

meet

the

needs

of

the

chronic

pain

patient.

□

Unrelieved

postoperative

pain

due

to

undermedication

may

provoke

withdrawal.

□

Patients

tend

to

underreport

their

medication.

□

With

uncontrolled

anxiety

or

fear

of

pain,

patients

tend

to

over-

estimate

the

effect

of

painful

stimuli.

□

Epidural

and

intravenous

(IV)

opioid

(including

patient-con-

trolled

analgesia

[PCA])

requirements

can

be

2-4

times

higher

in

opioid-consuming

than

in

opioid-naïve

patients.

□

Expect

prolonged

recovery

and

need

for

postoperative

analge-

sia.

□

Anxiety

and

insufficient

coping

result

in

poor

compliance

with

analgesic

strategies.

□

Individual

variations

in

response

to

opioids

may

necessitate

selection

of

the

optimal

drug

and

dosing

by

sequential

trials.

□

Individual

titration

of

doses

to

find

the

optimal

balance

be-

tween

analgesia

and

adverse

effects

is

required.

□

Adjuvant

medication

may

interfere

with

anesthesia

and

postop-

erative

analgesia.

BOX

51.1

Risk

Factors

in

the

Perioperative

Management

of

the

Chronic

Pain

Patient

Adapted

from

Kopf

A,

Banzhaf

A,

Stein

C.

Perioperative

manage-

ment

of

the

chronic

pain

patient.

Best

Pract

Res

Clin

Anaesthesiol.

2005;19:59–76.

202](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-61-320.jpg)

![Palliative

Medicine

1633

the

physician

and

patient

or

family

agree

to

reevaluate

the

benefit

after

a

specified

period,

may

be

helpful.

94

Time-

limited

trials

give

families

a

sense

of

when

the

health-

care

team

expects

to

know

whether

an

intervention

is

helping

and

creates

the

expectation

that

the

issue

will

be

readdressed.

RESUSCITATION

STATUS

Outcomes

of

Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation

CPR

was

introduced

around

1960,

initially

as

a

treatment

for

intraoperative

events

95

and

then

expanded

outside

the

surgical

unit.

Outcomes

of

CPR

have

improved,

with

over

PATIENT-TESTED

LANGUAGE

"I'd

like

to

talk

about

what

is

ahead

with

your

illness

and

do

some

thinking

in

advance

about

what

is

important

to

you

so

that

I

can

make

sure

we

provide

you

with

the

care

you

want

––

is

this

okay?"

"What

is

your

understanding

now

of

where

you

are

with

your

illness?"

"How

much

information

about

what

is

likely

to

be

ahead

with

your

illness

would

you

like

from

me?"

"I

want

to

share

with

you

my

understanding

of

where

things

are

with

your

illness

...

"

Uncertain:

"It

can

be

difficult

to

predict

what

will

happen

with

your

illness.

I

hope

you

will

continue

to

live

well

for

a

long

time

but

I'm

worried

that

you

could

get

sick

quickly,

and

I

think

it

is

important

to

prepare

for

that

possibility."

OR

Time:

"I

wish

we

were

not

in

this

situation,

but

I

am

worried

that

time

may

be

as

short

as

(express

as

a

range,

e.g.

days

to

weeks,

weeks

to

months,

months

to

a

year)."

OR

Function:

"I

hope

that

this

is

not

the

case,

but

I'm

worried

that

this

may

be

as

strong

as

you

will

feel,

and

things

are

likely

to

get

more

difficult."

"What

are

your

most

important

goals

if

your

health

situation

worsens?"

"What

are

your

biggest

fears

and

worries

about

the

future

with

your

health?"

"What

gives

you

strength

as

you

think

about

the

future

with

your

illness?"

"What

abilities

are

so

critical

to

your

life

that

you

can't

imagine

living

without

them?"

"If

you

become

sicker,

how

much

are

you

willing

to

go

through

for

the

possibility

of

gaining

more

time?"

"How

much

does

your

family

know

about

your

priorities

and

wishes?"

"I've

heard

you

say

that

is

really

important

to

you.

Keeping

that

in

mind,

and

what

we

know

about

your

illness,

I

recommend

that

we

.

This

will

help

us

make

sure

that

your

treatment

plans

reflect

what's

important

to

you."

"How

does

this

plan

seem

to

you?"

"I

will

do

everything

I

can

to

help

you

through

this."

SET

UP ASSESS SHARE EXPLORE CLOSE

Fig.

52.7

Serious

illness

conversation

guide.

(2015

to

2017

Ariadne

Labs:

A

Joint

Center

for

Health

Systems

Innovation

[www.ariadnelabs.org]

between

Brigham

and

Women’s

Hospital

and

the

Harvard

T.H.

Chan

School

of

Public

Health,

in

collaboration

with

Dana-Farber

Cancer

Institute.

Licensed

under

the

Creative

Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

4.0

International

License,

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-

nc-sa/4.0/.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-66-320.jpg)

![Anesthesia

for

Cardiac

Surgical

Procedures

1739

wall

motion

abnormalities.

Reopening

the

chest

may

be

necessary

while

treatment

is

instituted.

Occasionally,

the

patient’s

sternum

cannot

be

closed

because

of

hemo-

dynamic

instability;

in

such

cases,

only

skin

closure

is

attempted,

and

plans

are

made

to

return

to

the

operat-

ing

room

for

sternal

wiring

after

a

period

of

myocardial

recovery

in

the

ICU.

TRANSPORT

TO

THE

INTENSIVE

CARE

UNIT

Transportation

of

postcardiac

surgical

patients

to

the

ICU

is

frequently

dangerous

and

underestimated.

Prepara-

tion

for

transportation

of

a

postcardiac

surgical

patient

should

start

with

evaluation

of

the

stability

of

the

patient

in

the

operating

room.

An

ICU

bed

with

a

portable

-

Checklist

1.

Rectal/bladder

T˚

>

35.5˚

C

2.

Hct

25%,

K

+

3.8–5

mEq,

pH

>

7.3,

glycemia

6–9

mm/L

3.

Surgeon

→

aortic

unclamping

±

De-airing

cardiac

cavities

±

Defibrillation

4.

Lung

reventilation

5.

Spontaneous

or

paced

HR

(>

70

beats/min)

6.

TEE

examination

under

partial

CPB

→

Check

for

structural

defects

→

Check

for

functional

defects

Step

1

Hemodynamic

targets

Step

3

Mechanical

circulatory

support

→

Successful

CPB

weaning

Protamine

IV

and

ACT

control

Inability

to

wean

from

CPB

despite

preload

optimization

and

adequate

surgical

repair

(exclude

valve

dysfunction,

coronary

graft

failure,

LV

outflow

tract

obstruction)

Inability

to

wean

from

CPB

despite

preload

and

pharmacologic

optimization

(MAP

<

70,

Cl

<

2.0

L/min/m

2

,

SvO

2

<

70%,

elevated

[lactate])

HR

70–100

Optimize

preload

High

MAP

70–90

mm

Hg

<

70

mm

Hg

2+

,

K

+

venous

return

and

pump

flow:

100%

–

75%

–

50%

–

25%

–

0

(reservoir,

cell-saver)

1.

Inotropes

±

vasopressors

Or

levosimendan

(or

milrinone)

+

norepinephrine

2.

Stepwise

reduction

of

venous

return

and

pump

flow:

100%

–

75%

–

50%

–

25%

–

0

3.

Cardiac

pacing:

biventricular,

atrioventricular

4.

Inhaled

NO

(PGI

2

)

if

PH,

RV

failure

(NTG,

NPS)

Vasopressors

1.

Norepinephrine,

phenylephrine

2.

Terlipressin

3.

(Methylene

blue)

>

100

beats/min

Arrhythmia

<

70

beats/min

or

conduction

block

>

90

mm

Hg

Step

2

TEE

Ventricular

function

Vasoplegic

syndrome

Ventricular

failure

Appropriate

Impaired

→

Successful

CPB

weaning

Protamine

IV

and

ACT

control

Fig.

54.11

Algorithm

for

weaning

from

cardiopulmonary

bypass

(CPB).

ACT,

Activated

clotting

time;

Hct,

hematocrit;

HR,

heart

rate;

IV,

intravenous;

K

+

,

potassium;

LV,

left

ventricular;

MAP,

mean

arterial

pressure;

Mg

2+

,

magnesium;

NO,

nitric

oxide;

NPS,

sodium

nitroprusside;

NTG,

nitroglycerin;

PGI

2

,

prostacyclin;

PH,

pulmonary

hypertension;

RV,

right

ventricular;

SvO

2

,

mixed

venous

oxygen

saturation;

TEE,

transesophageal

echocardiography.

(From

Licker

M,

Diaper

J,

Cartier

V,

et

al.

Clinical

review:

management

of

weaning

from

cardiopulmonary

bypass.

Ann

Card

Anaesth.

2012;15:206–223.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/millercharts-220915004659-e44e6ffc/85/Miller-charts-pdf-101-320.jpg)

![Anesthesia

and

the

Renal

and

Genitourinary

Systems

1933

Patients

remain

asymptomatic

with

only

biochemical

evi-

dence

of

a

decline

in

GFR

(i.e.,

an

increase

in

serum

concen-

trations

of

urea

and

creatinine).

Further

workup

usually

reveals

other

abnormalities,

such

as

nocturia,

anemia,

loss

of

energy,

decreasing

appetite,

and

abnormalities

in

cal-

cium

and

phosphorus

metabolism.

As

the

GFR

decreases

further,

a

stage

of

severe

renal

insufficiency

begins.

This

stage

is

characterized

by

pro-

found

clinical

manifestations

of

uremia

and

biochemical

abnormalities,

such

as

acidemia;

volume

overload;

and

neurologic,

cardiac,

and

respiratory

manifestations.

At

the

stages

of

mild

and

moderate

renal

insufficiency,

intercur-

rent

clinical

stress

may

compromise

renal

function

further

and

induce

signs

and

symptoms

of

overt

uremia.