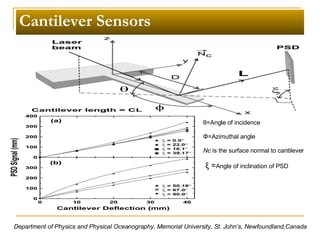

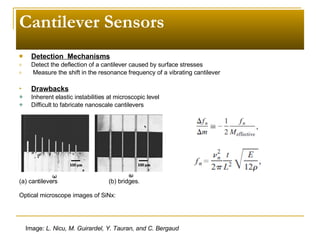

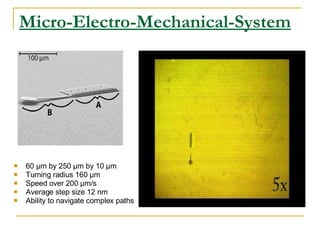

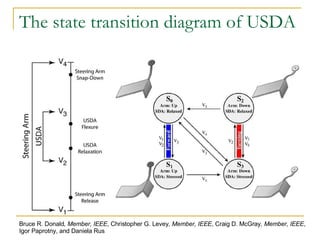

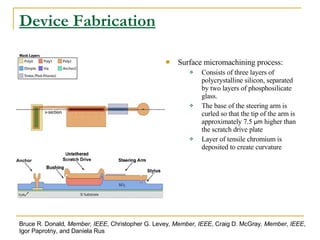

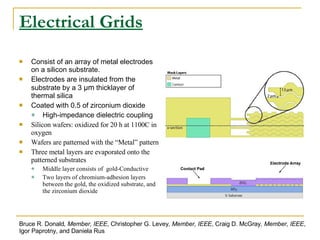

The document discusses the challenges and opportunities in developing micro robots at the micrometer scale. It covers fabrication methods using materials like polymers, metals and carbon nanotubes. It also discusses actuators, sensors like cantilever sensors, and applications in medical, industrial and space domains. Future directions include realizing self-assembling microfactories and using micro robots for hazardous applications.