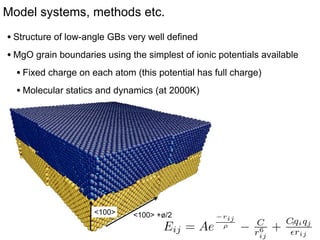

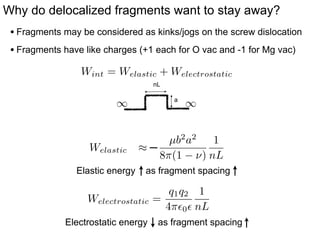

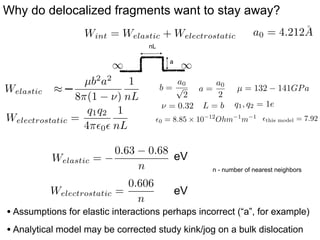

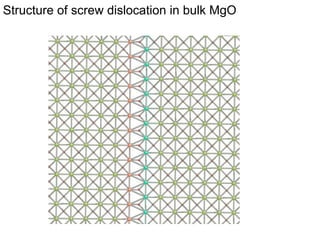

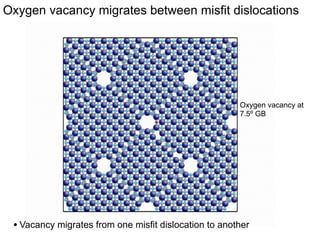

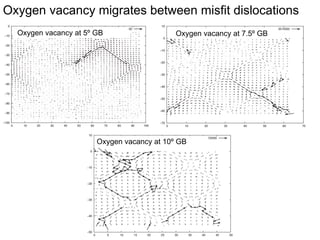

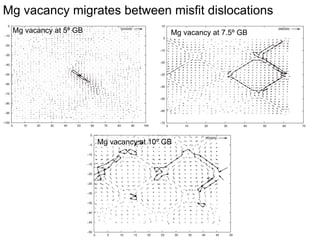

1. The authors studied the structure and transport of oxygen vacancies in MgO grain boundaries using molecular statics and dynamics simulations with a simple ionic potential model.

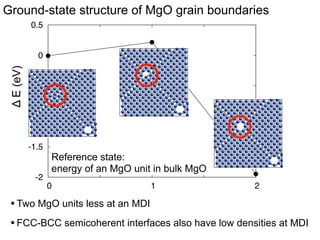

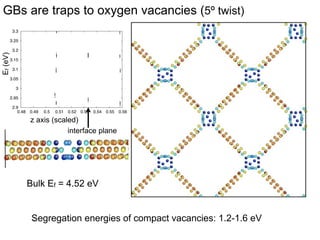

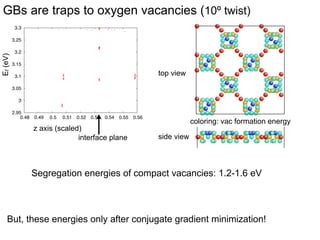

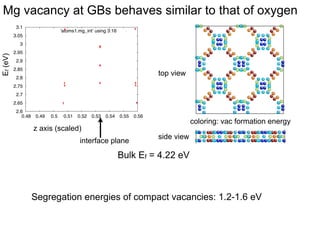

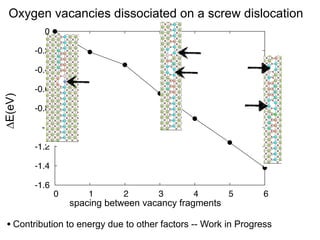

2. They found that grain boundaries act as traps for oxygen vacancies, with segregation energies of compact vacancies in the range of 1.2-1.6 eV.

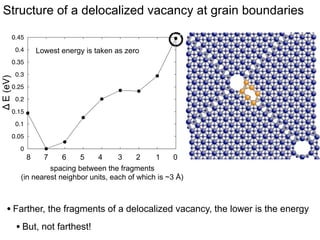

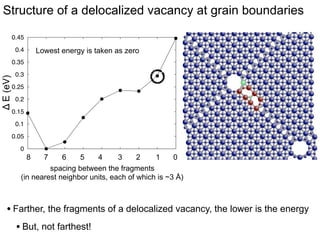

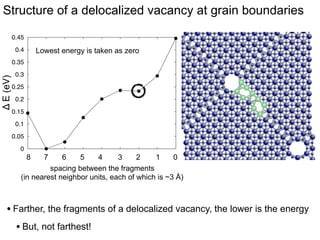

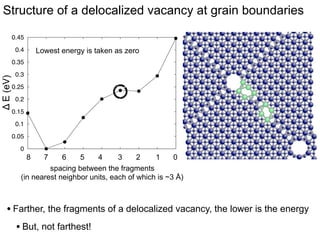

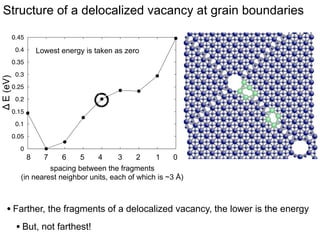

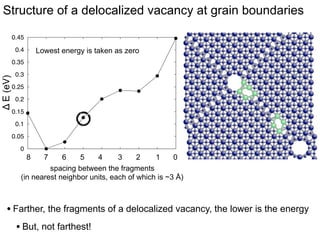

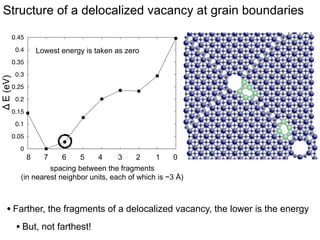

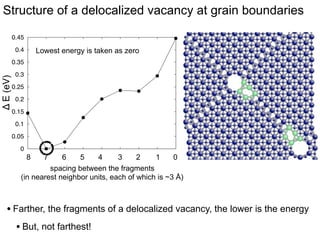

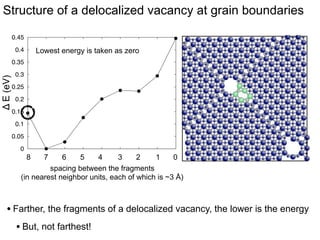

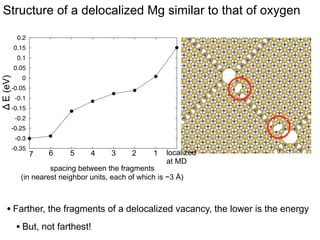

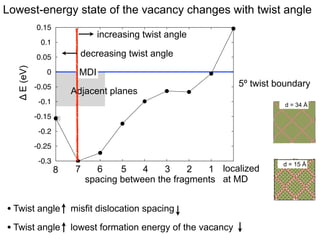

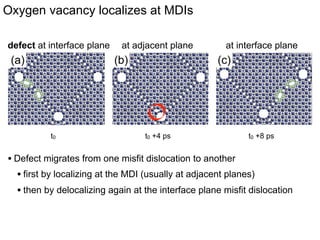

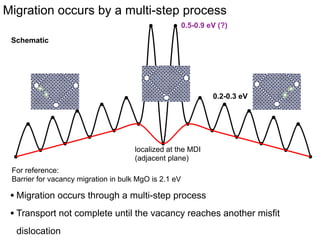

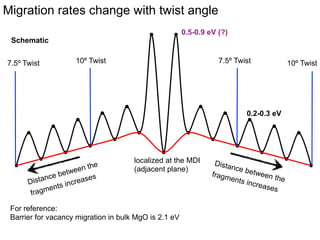

3. The vacancies can also exist in a delocalized state, where the vacancy fragments are separated across multiple atomic planes near the grain boundary. Delocalized configurations were found to have lower energies when the fragments were separated by an intermediate distance.

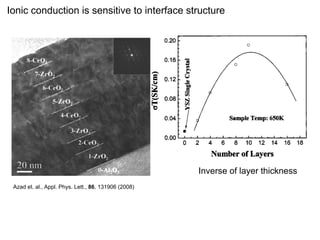

![the

yers

The

nm.

ystal

hick

minal

ance

as a

ni.

ductrs at

are

con-

abrupt conductivity decrease when the thickness

ionic conductivity of this material, which imposes results (fig. S1), meaning that the ultrathin layer range or sd

changes from 30 to 62 nm is most likely due to

rather high operational temperatures around 800°C a of YSZ grows rotated by 45° around the c axis obtained fr

degraded search for alternative electrolytes has

(1–4). Theinterface structure when the YSZ layers and strains to match the STO lattice. Because the frequency p

exceed the critical thickness.

not yet been successful in reaching the conduc- bulk lattice constants of STO and YSZ are due to grai

tivity value of 0.01 S/cm desired for room temperature operation (1–4).

Only modest reductions in the operation

temperature of SOFCs (500° to 700°C) can be

anticipated with the recently proposed optimized

electrolytes such as gadolinia-doped ceria and

lanthanum gallates (8–11). On the other hand, the

one to two orders of magnitude increase of the

electrical conductivity reported (12–14) in nanocrystalline samples as compared with single crystals outlines the importance of processing as an

alternative route to increasing conductivity values

toward the desired levels. Because modern thin

film growth techniques allow a precise control of

layer thickness and morphology, they provide a

pathway for the production of solid electrolytes

with optimized properties. Maier et al. found a

substantial increase of the dc ionic conductivity

of superlattices of CaF2 and BaF2 when the Fig. 1. (A) Z-contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy (S

thickness of the individual layers was decreased the [YSZ1nm/STO10nm]9 superlattice (with nine repeats), obtain

J. assigned to a size effect due to microscope. 676 (2008)

down to 16 nm, Garcia-Barriocanal et. al., Science, 321,A yellow arrow marks the position of the YSZ layer. (In

the space charge regions being smaller than the in the VG Microscopes HB501UX column. In both cases a white arrow

layer thickness (15, 16). Kosacki et al. have spectra showing the O K edge obtained from the STO unit cell at the

reported enhanced conductivity in highly tex- into the STO layer (black squares). (Inset) Ti L2,3 edges for the same

tured thin films of YSZ with thicknesses between are the result of averaging four individual spectra at these position

60 and 15 nm, reaching 0.6 S/cm at 800°C (17).

Because reducing film thickness (and therefore Fig. 2. Real part of the lateral

increasing the fraction of material near the in- electrical conductivity versus fre-

Solid Interfaces can enhance mass transport

www.sciencemag.org on September 17, 2011

scaling,

ductance

the large

res orig-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mgomrsv3-130409111956-phpapp01/85/Fall-MRS-2013-MgO-grain-boundaries-structure-and-transport-2-320.jpg)