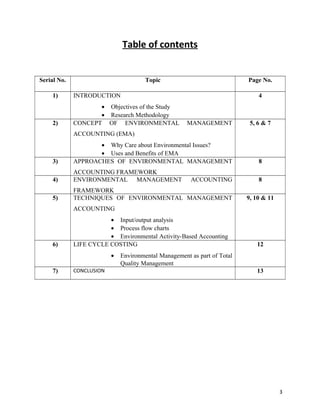

This document is an assignment submitted by a group of students at Green University of Bangladesh on the topic of environmental management accounting. It contains an introduction outlining the objectives and research methodology. The main body defines environmental management accounting, discusses why companies should care about the environment and the uses and benefits of EMA. It also outlines the key approaches and techniques of environmental management accounting frameworks, including input/output analysis, process flow charts, and activity-based costing. The conclusion states that clearly defining environmental costs is important for increased use of EMA.