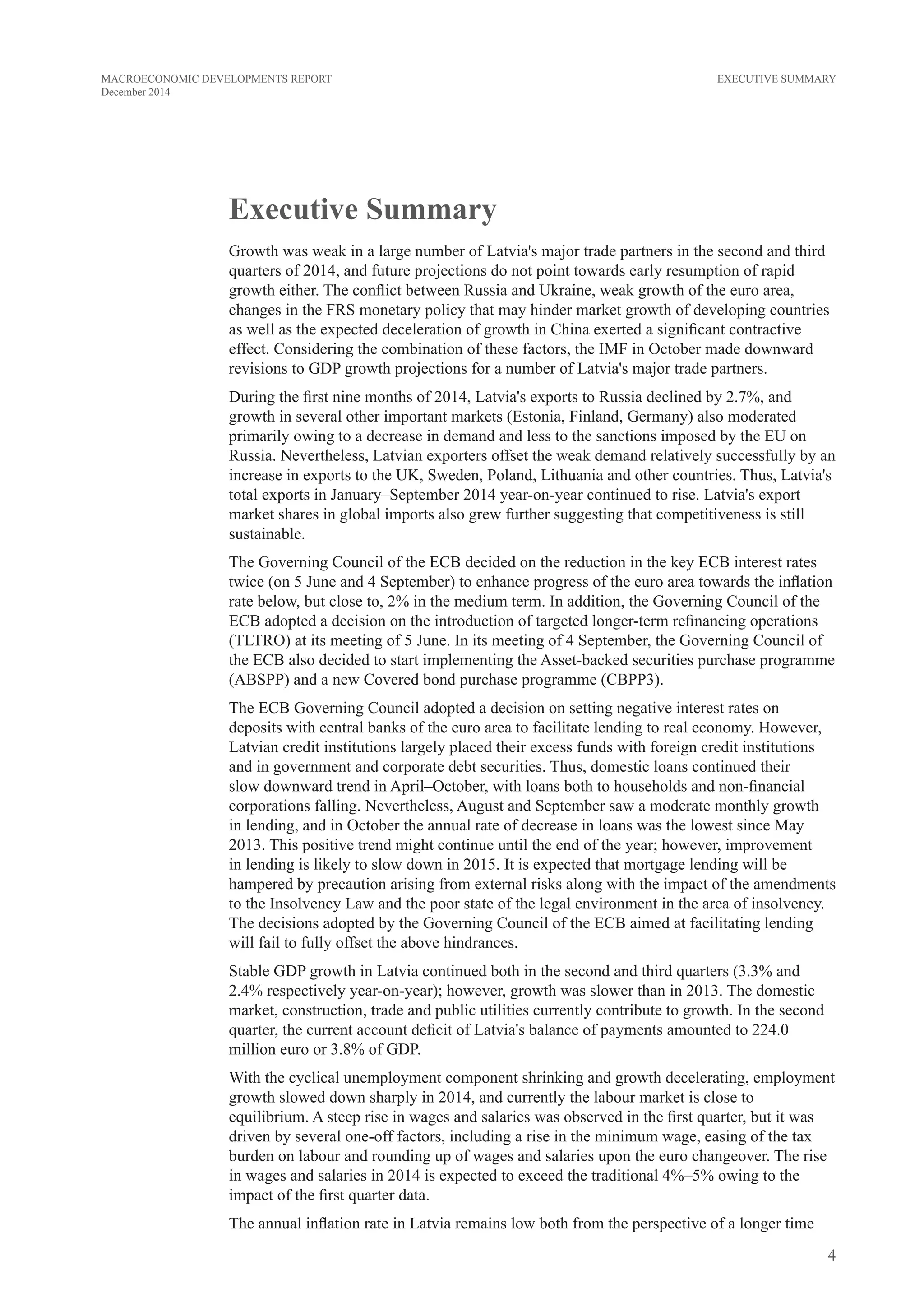

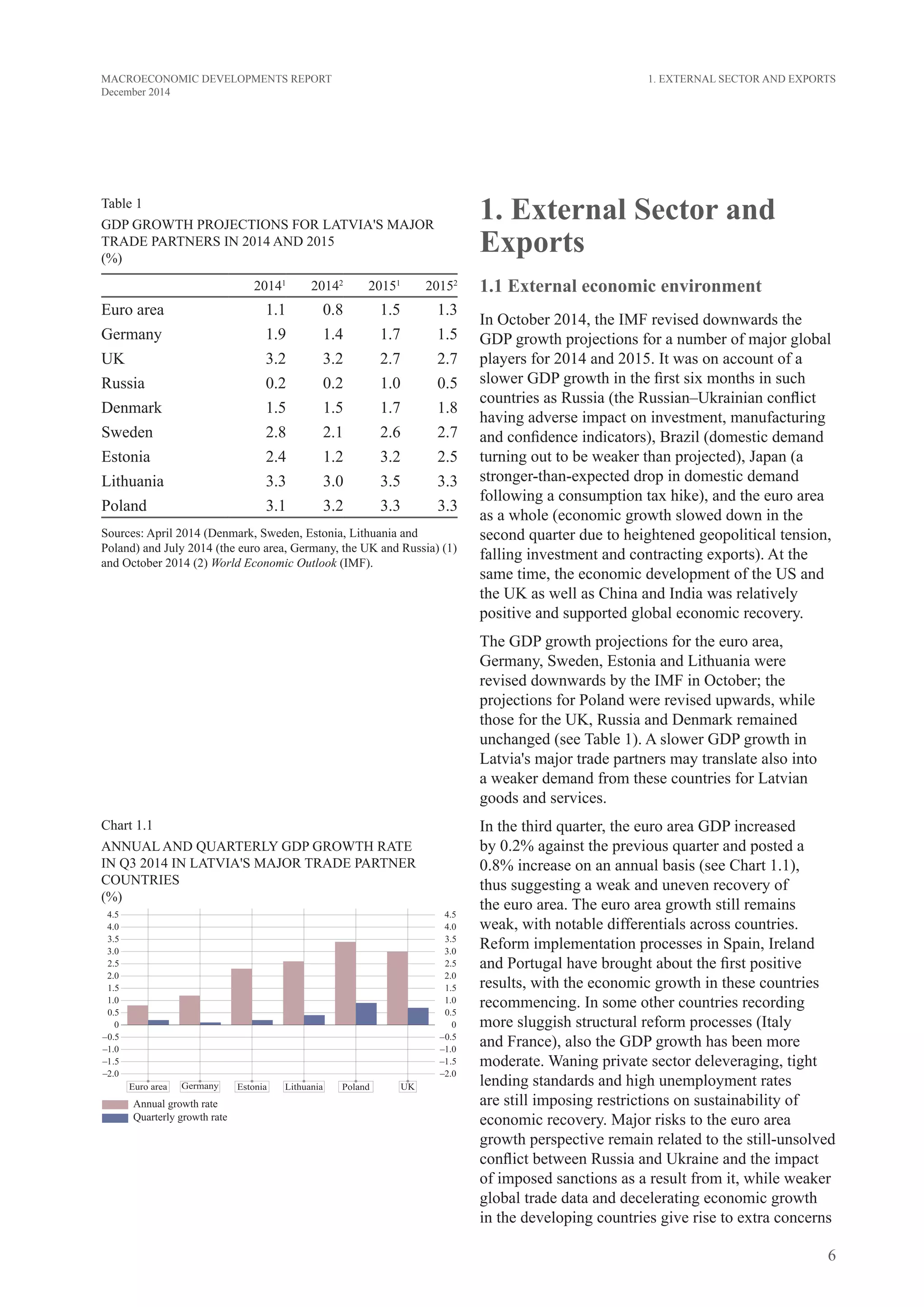

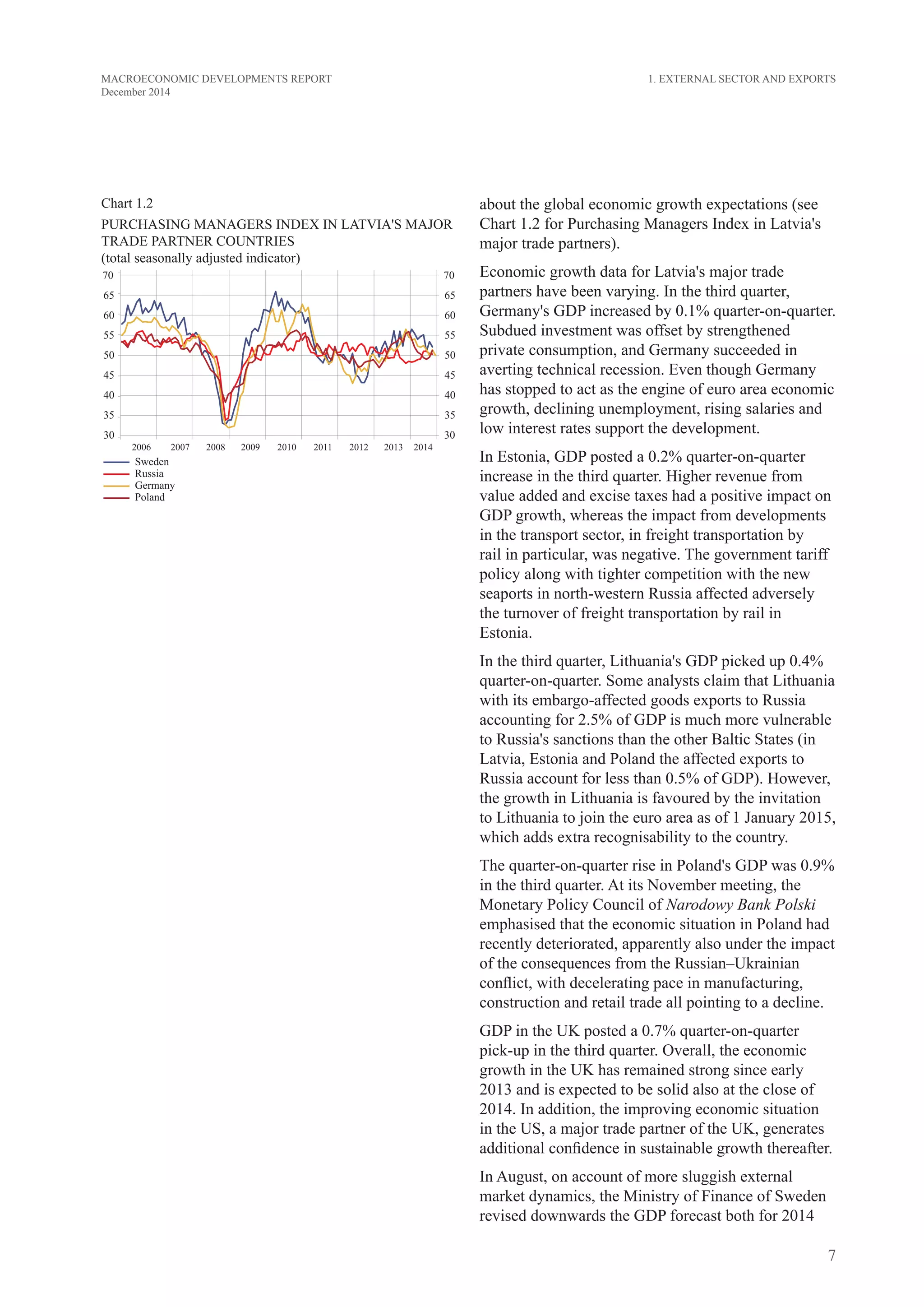

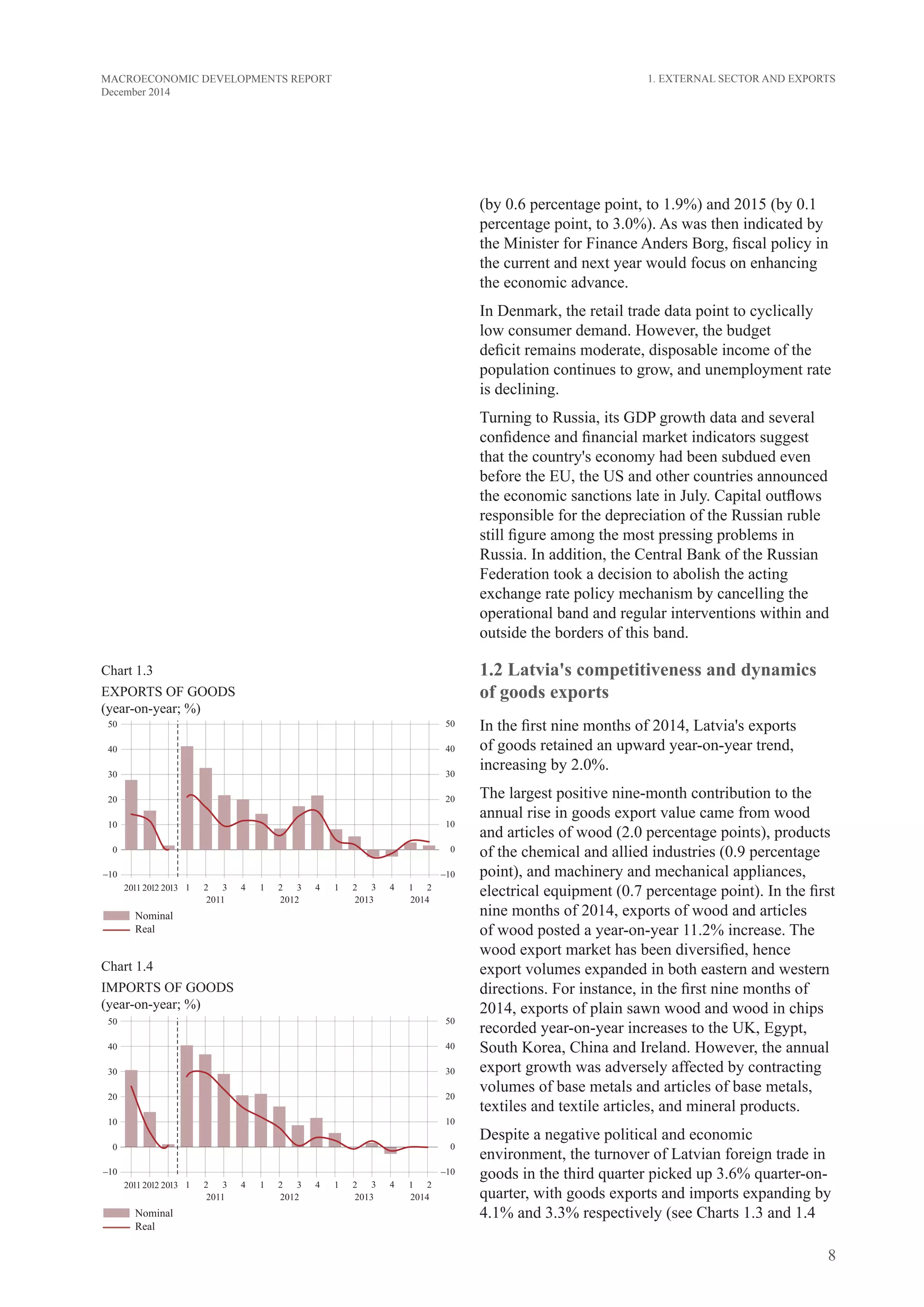

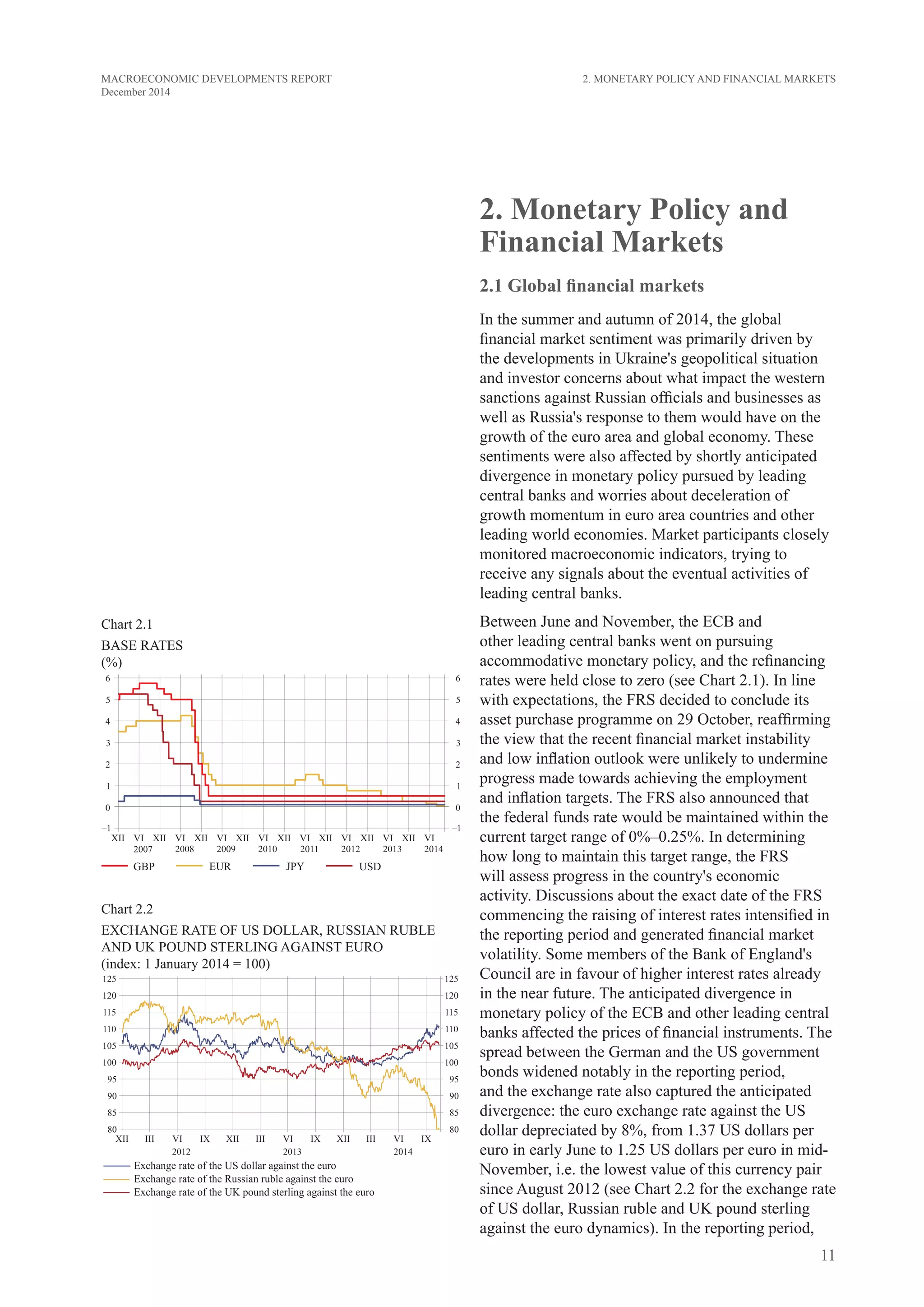

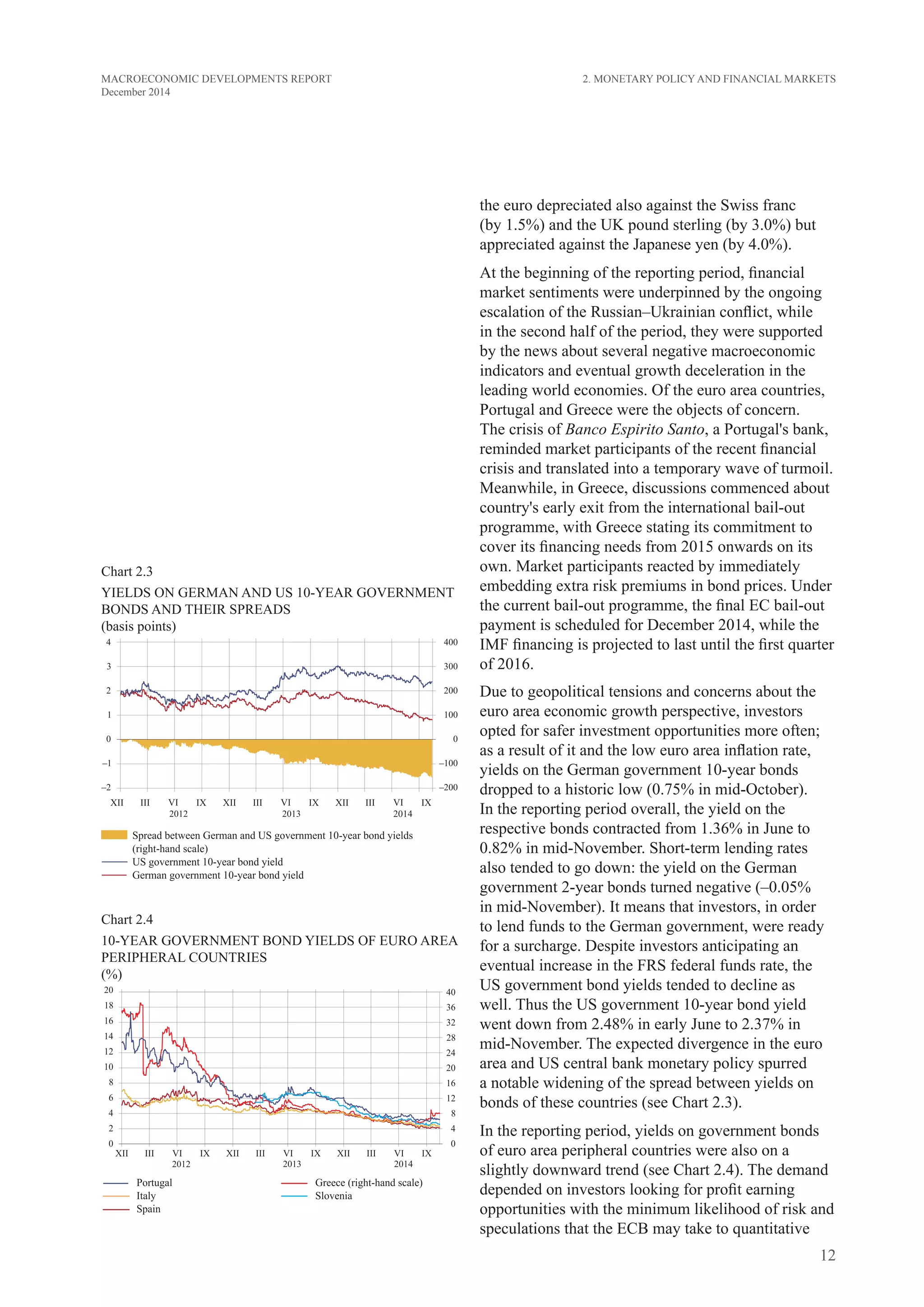

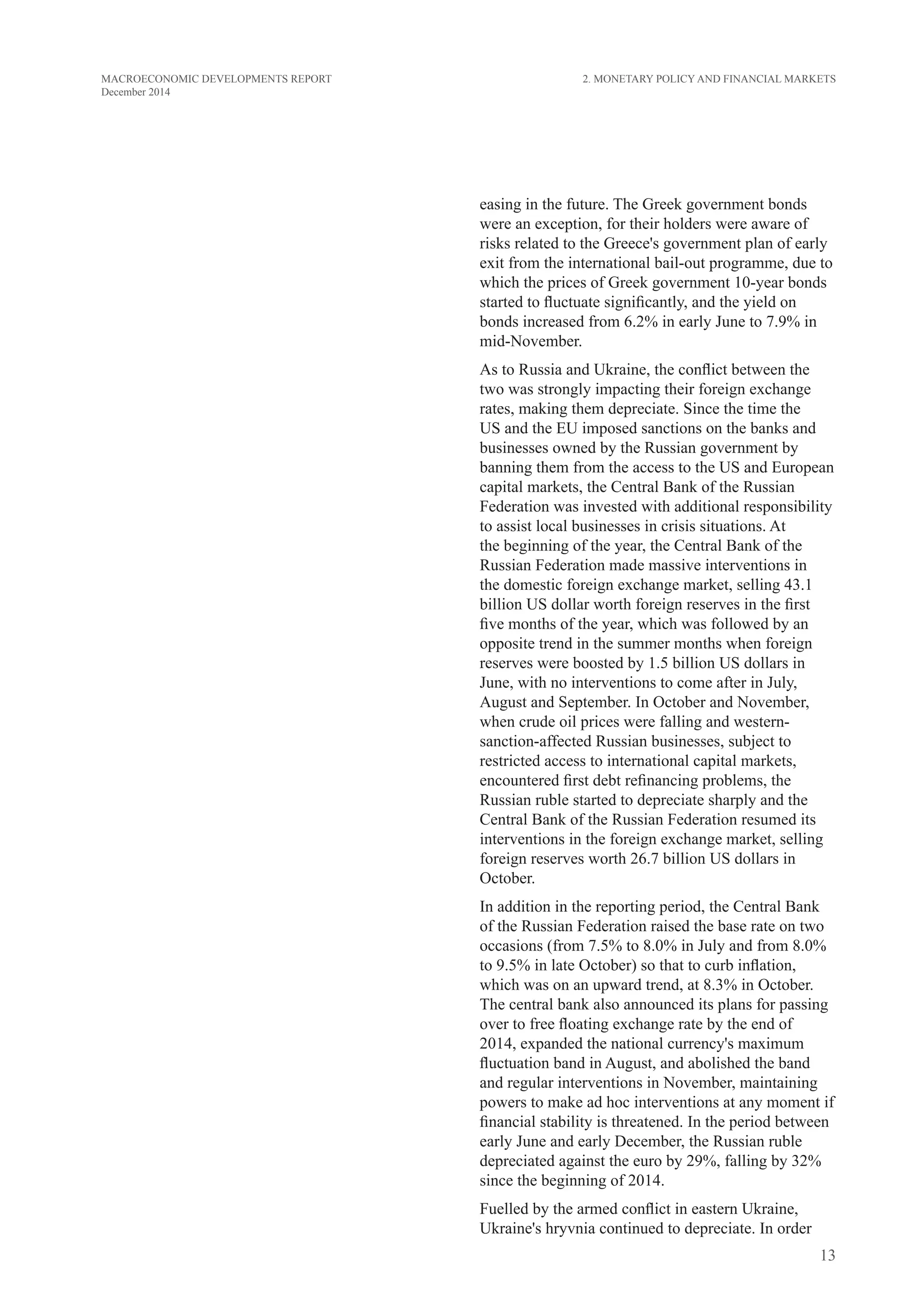

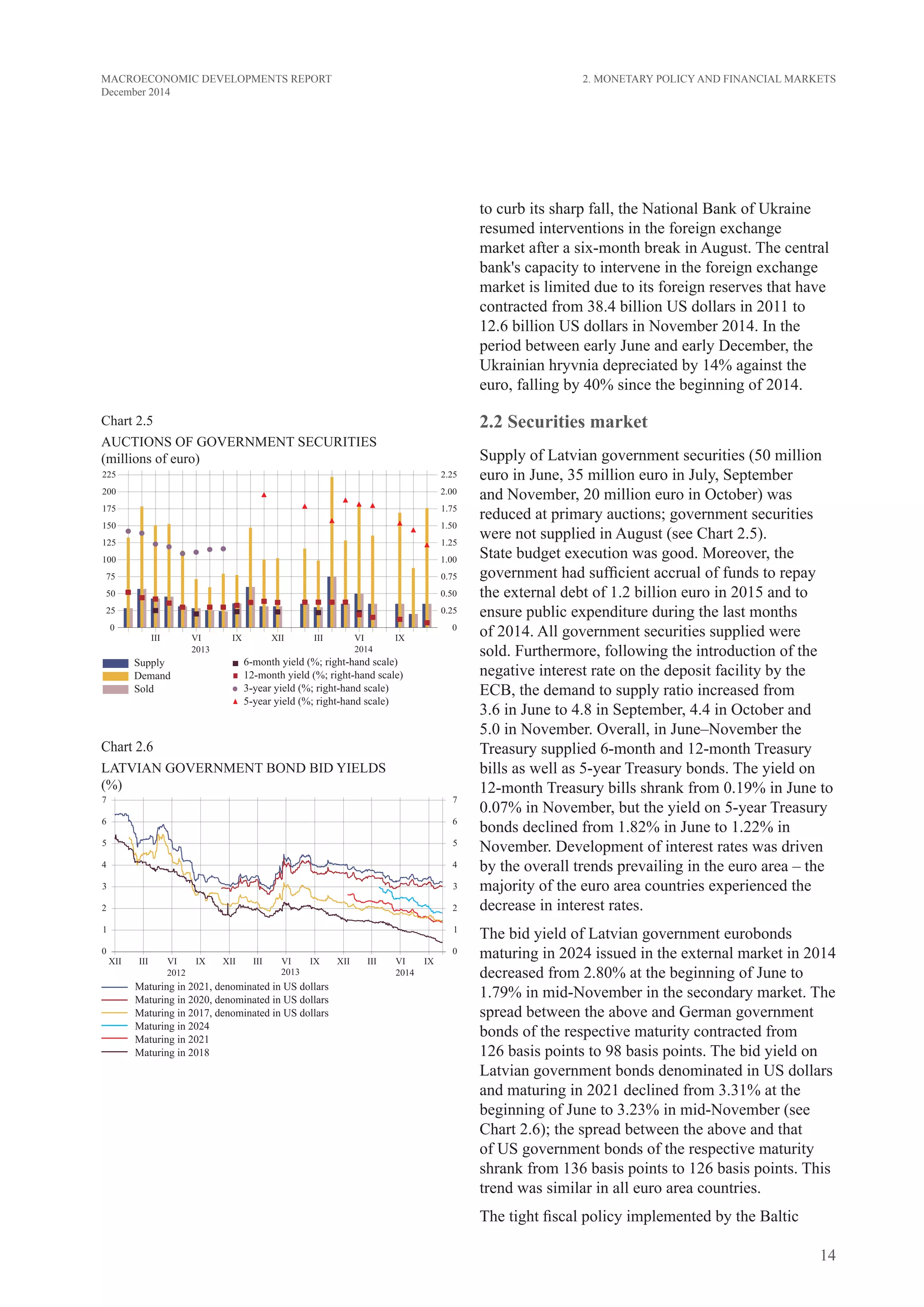

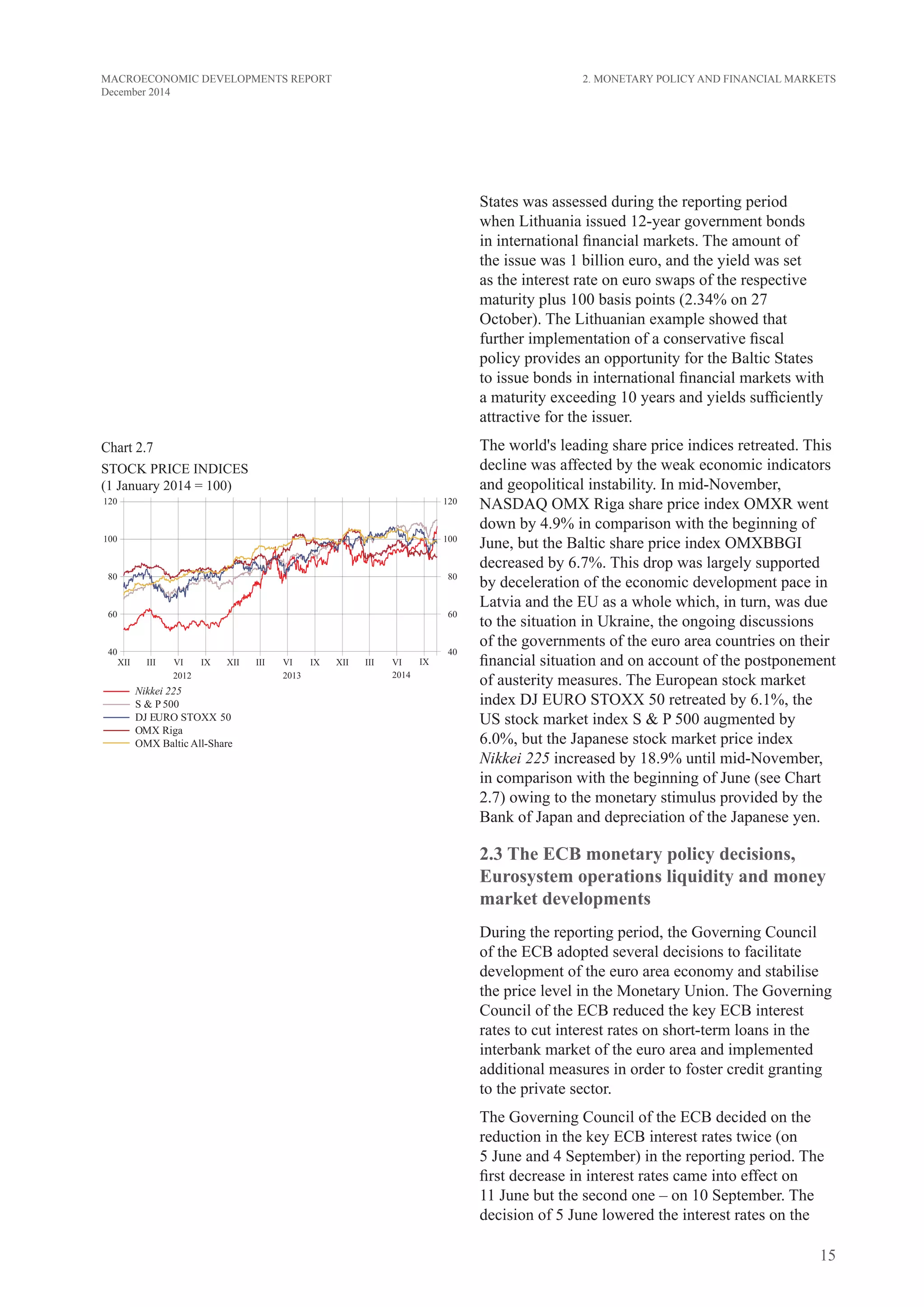

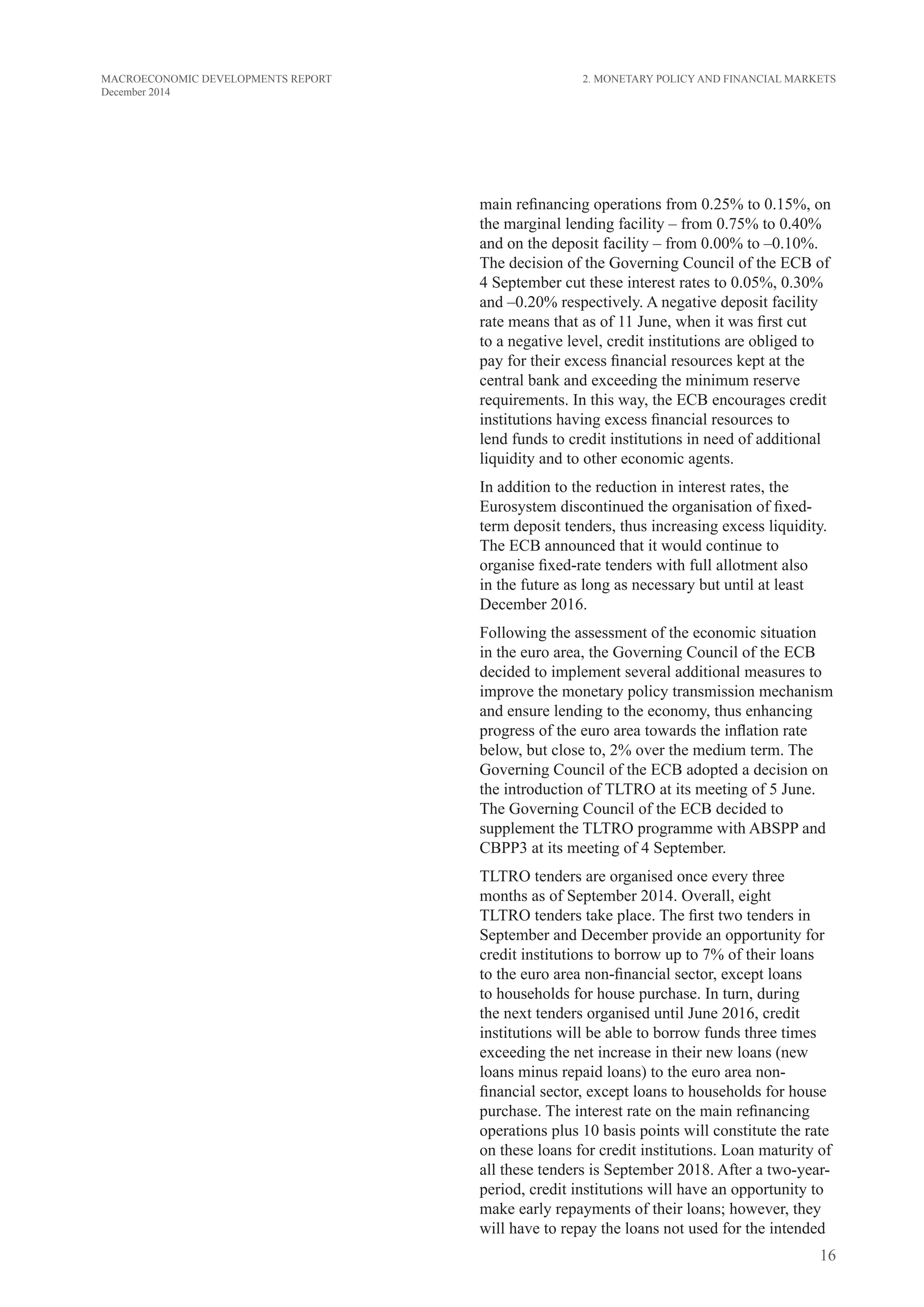

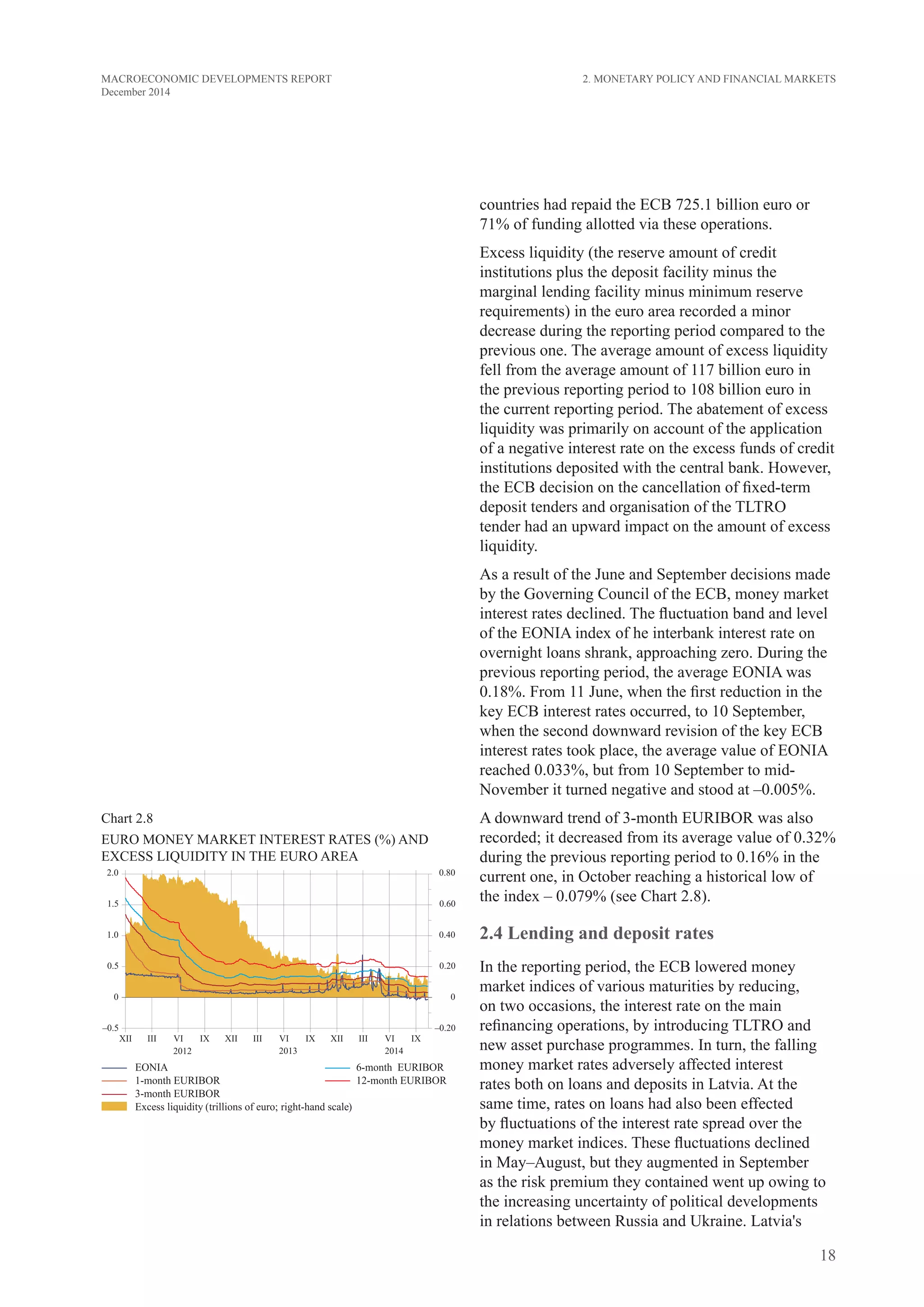

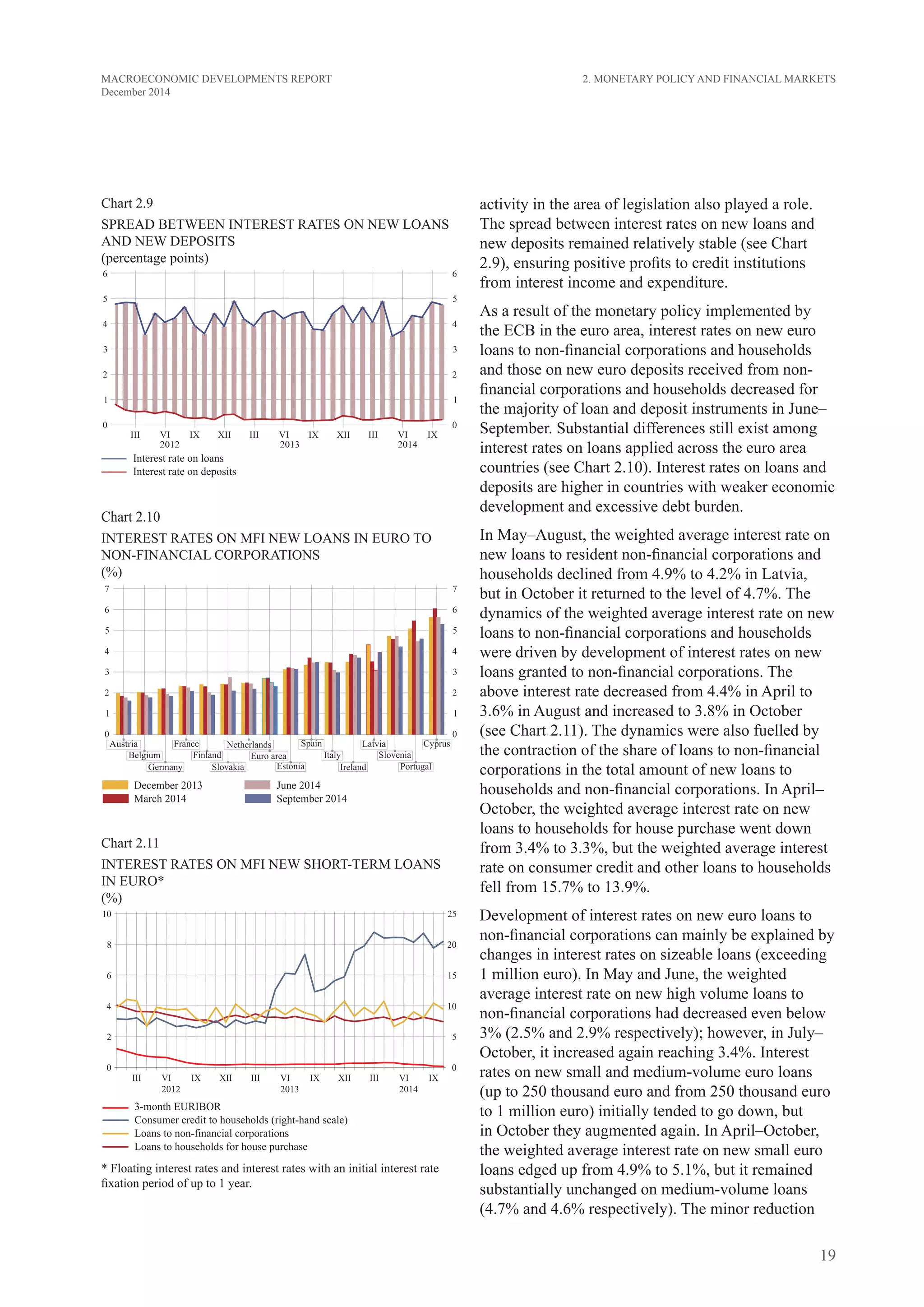

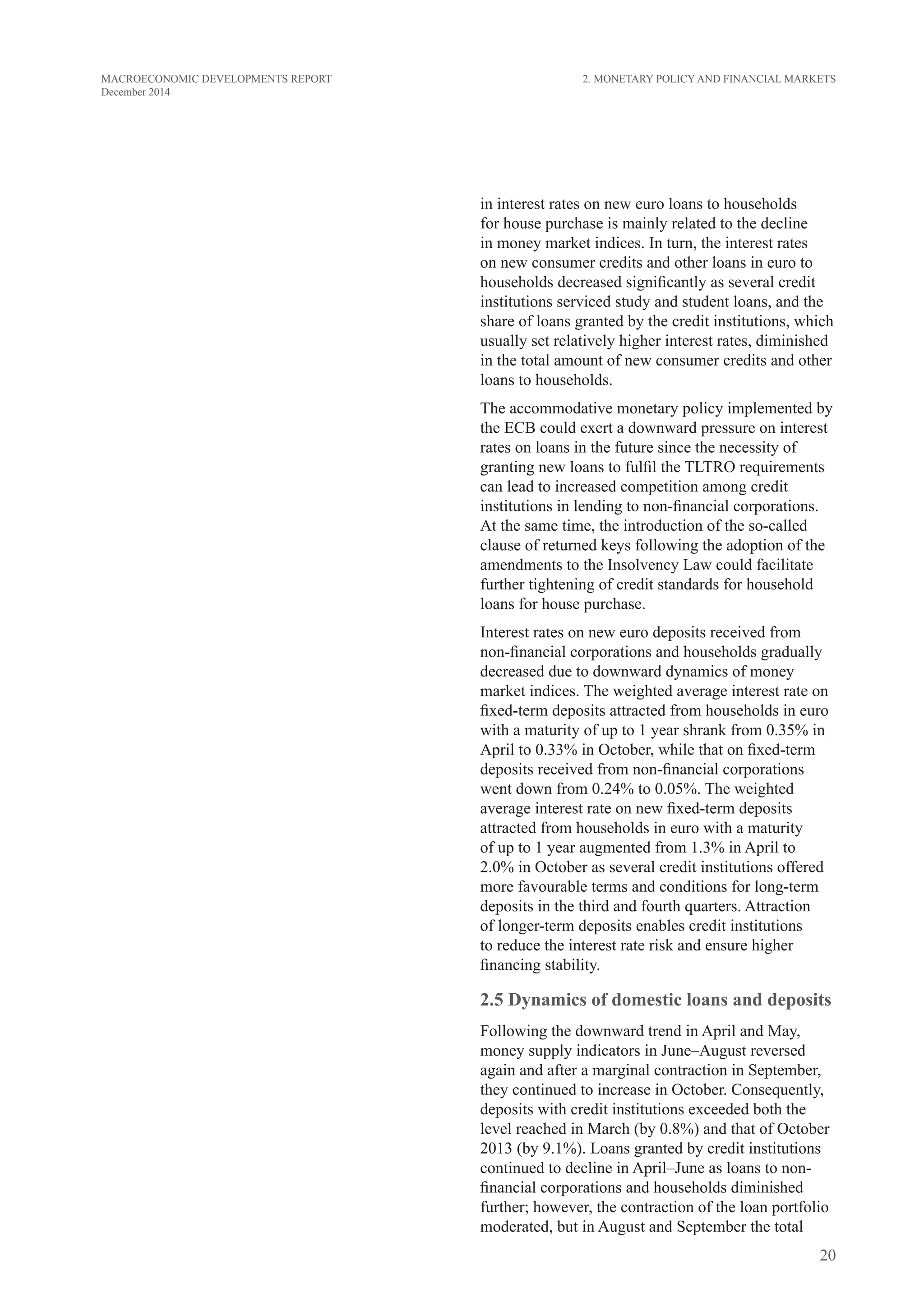

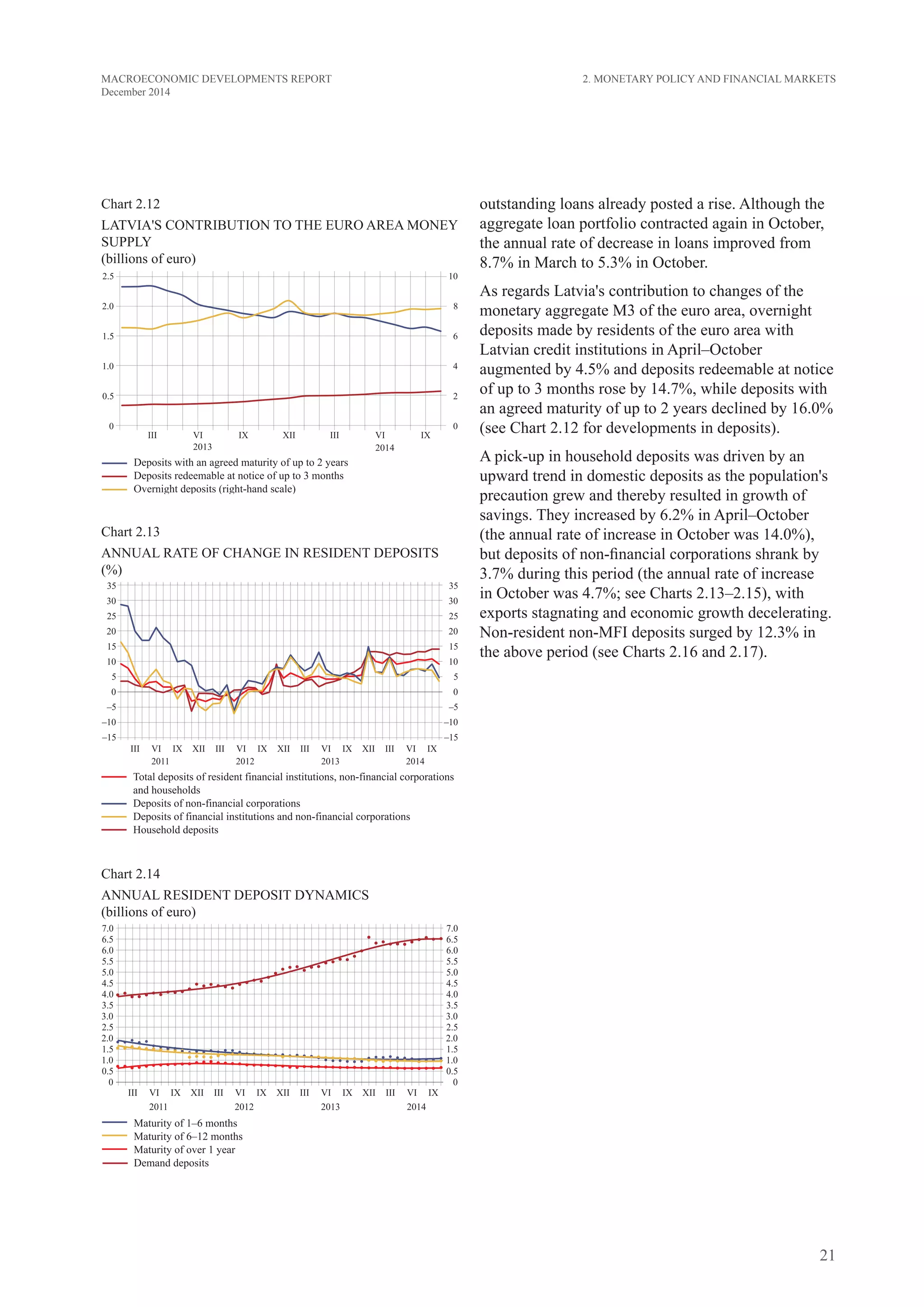

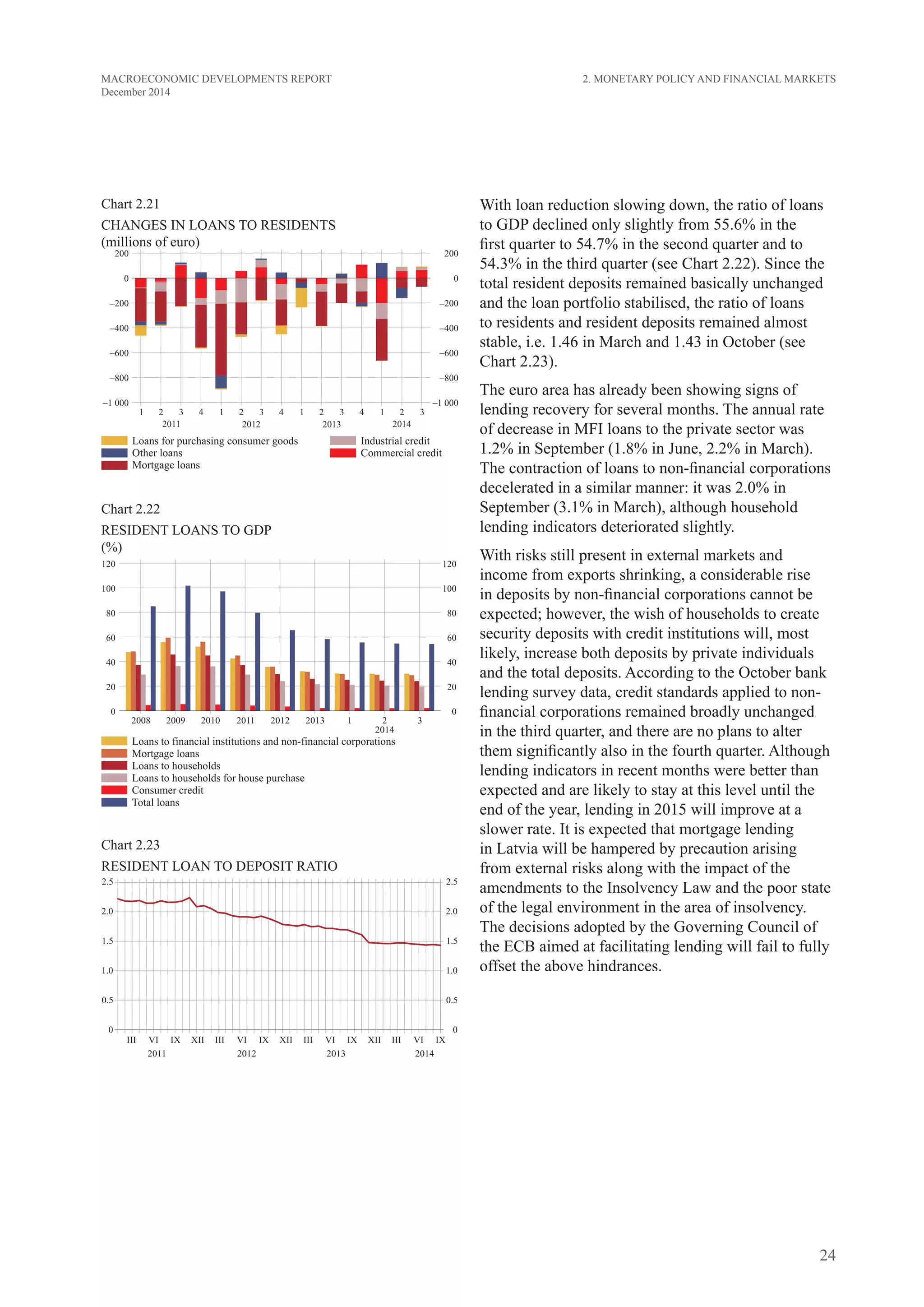

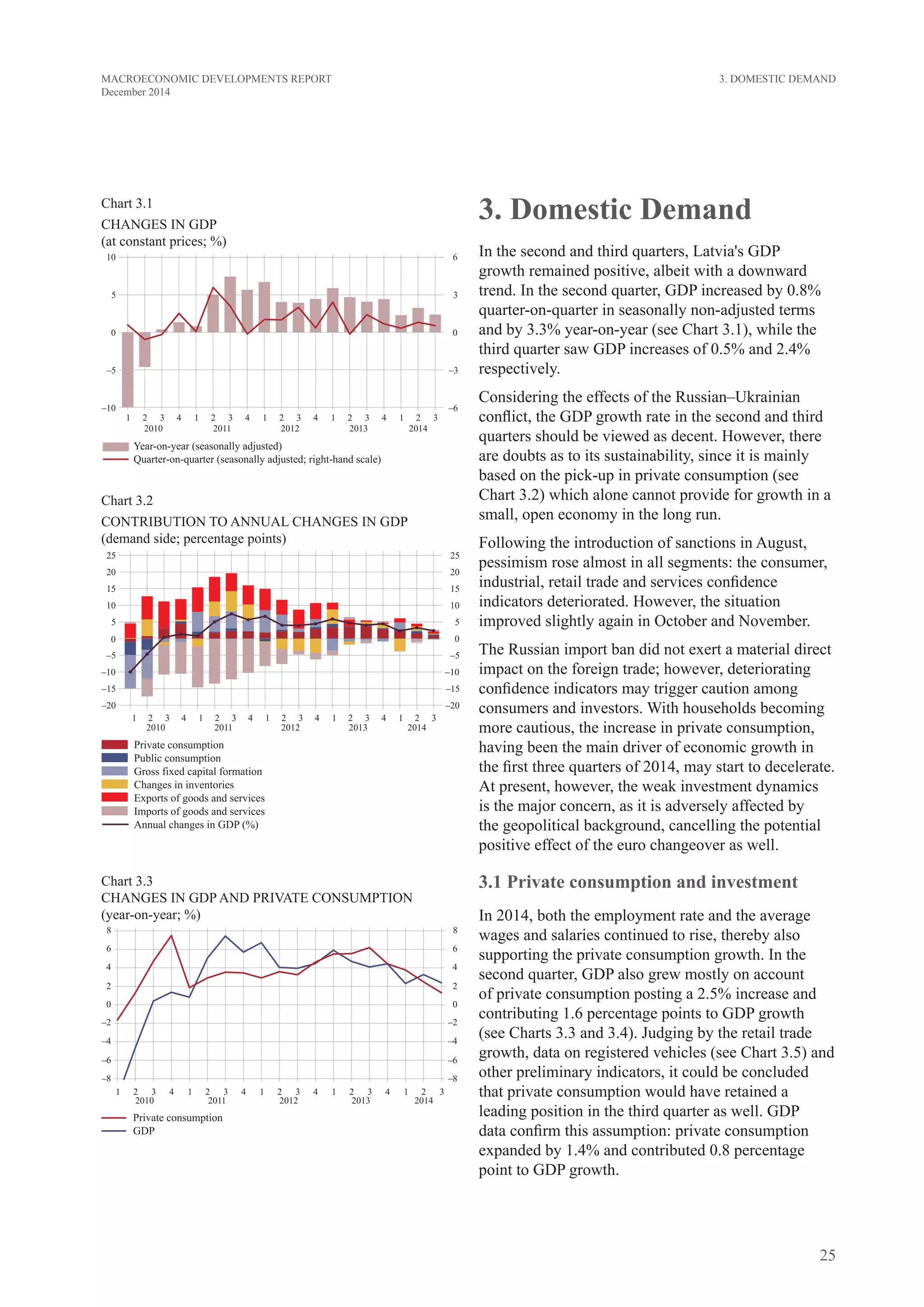

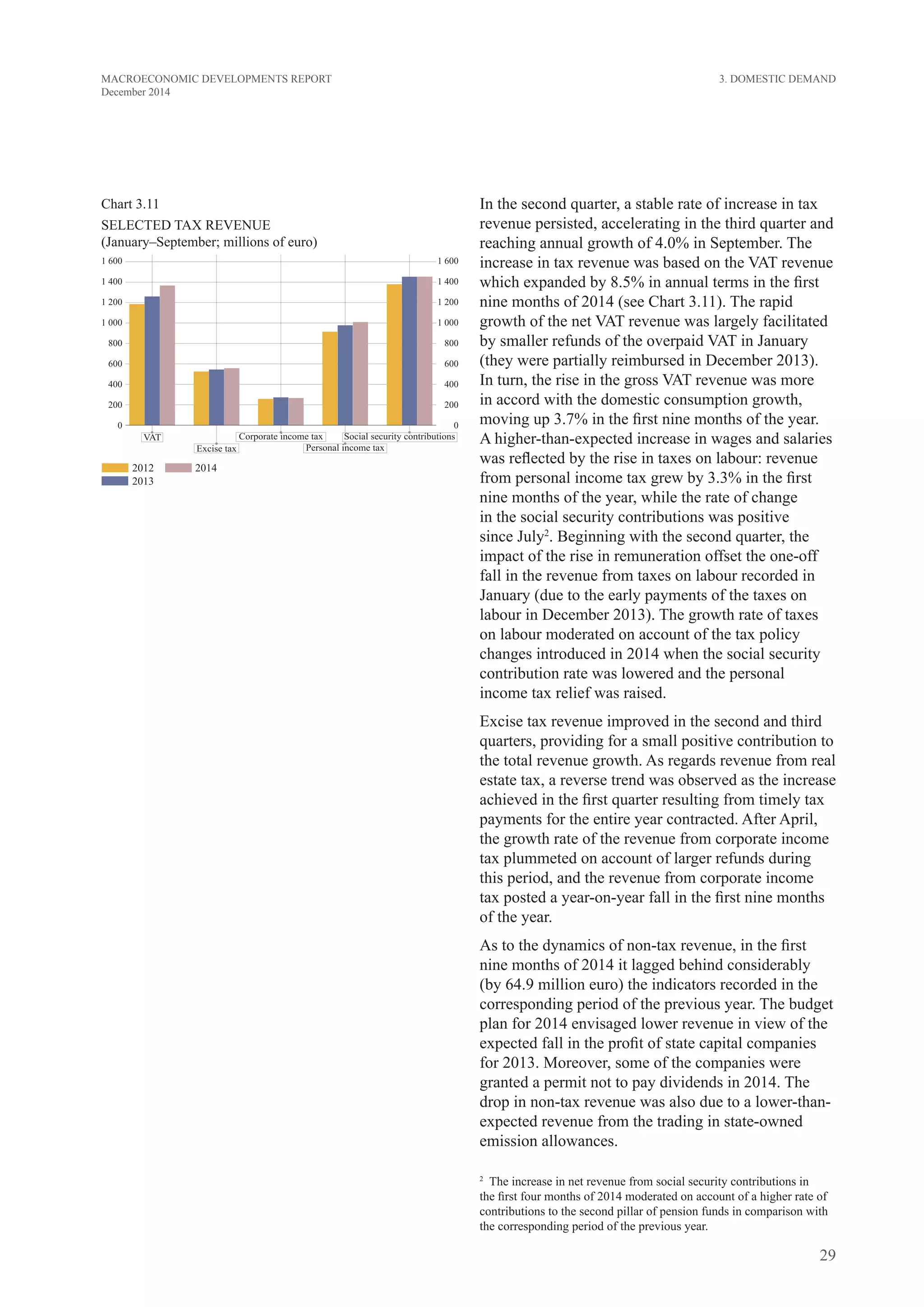

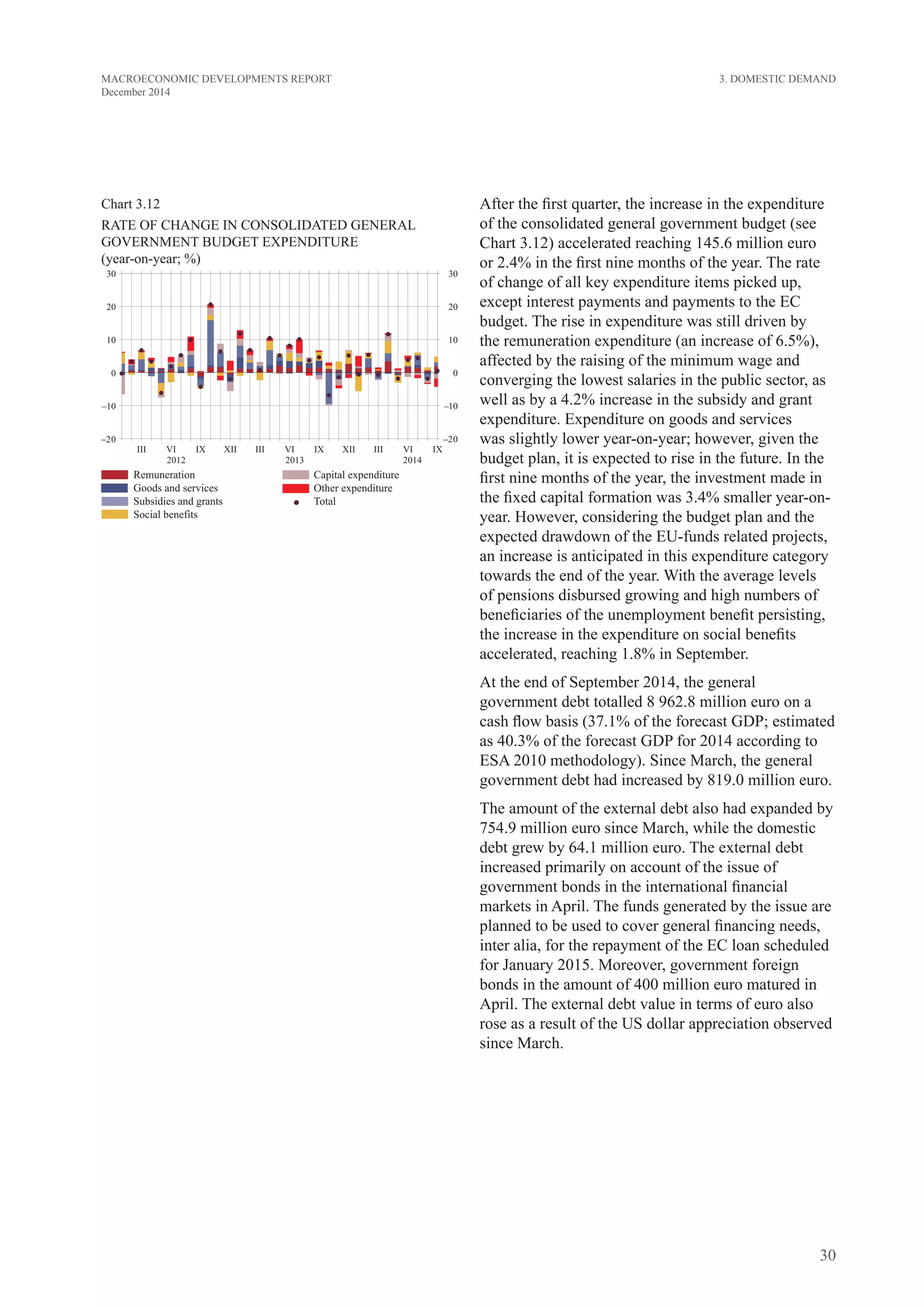

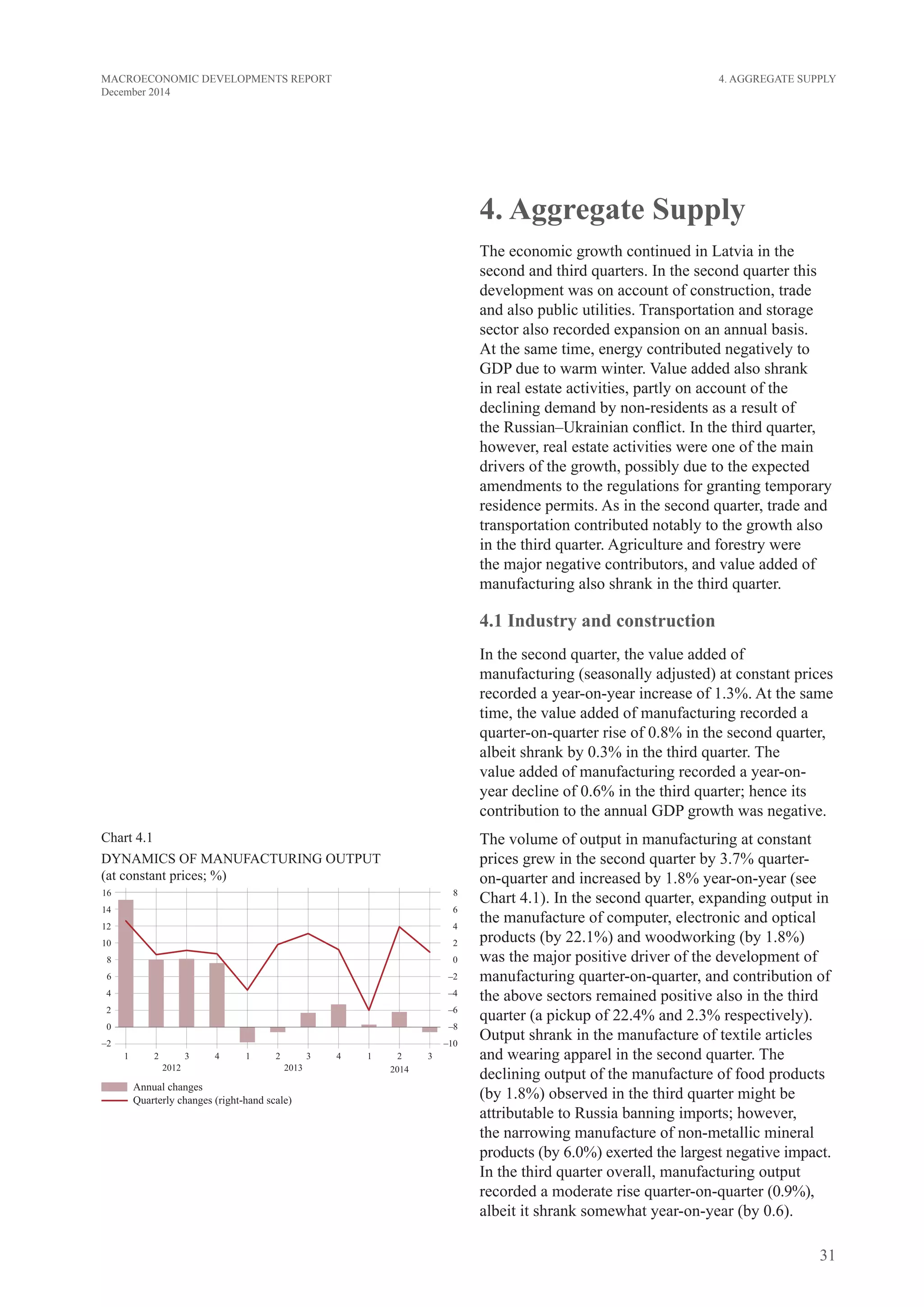

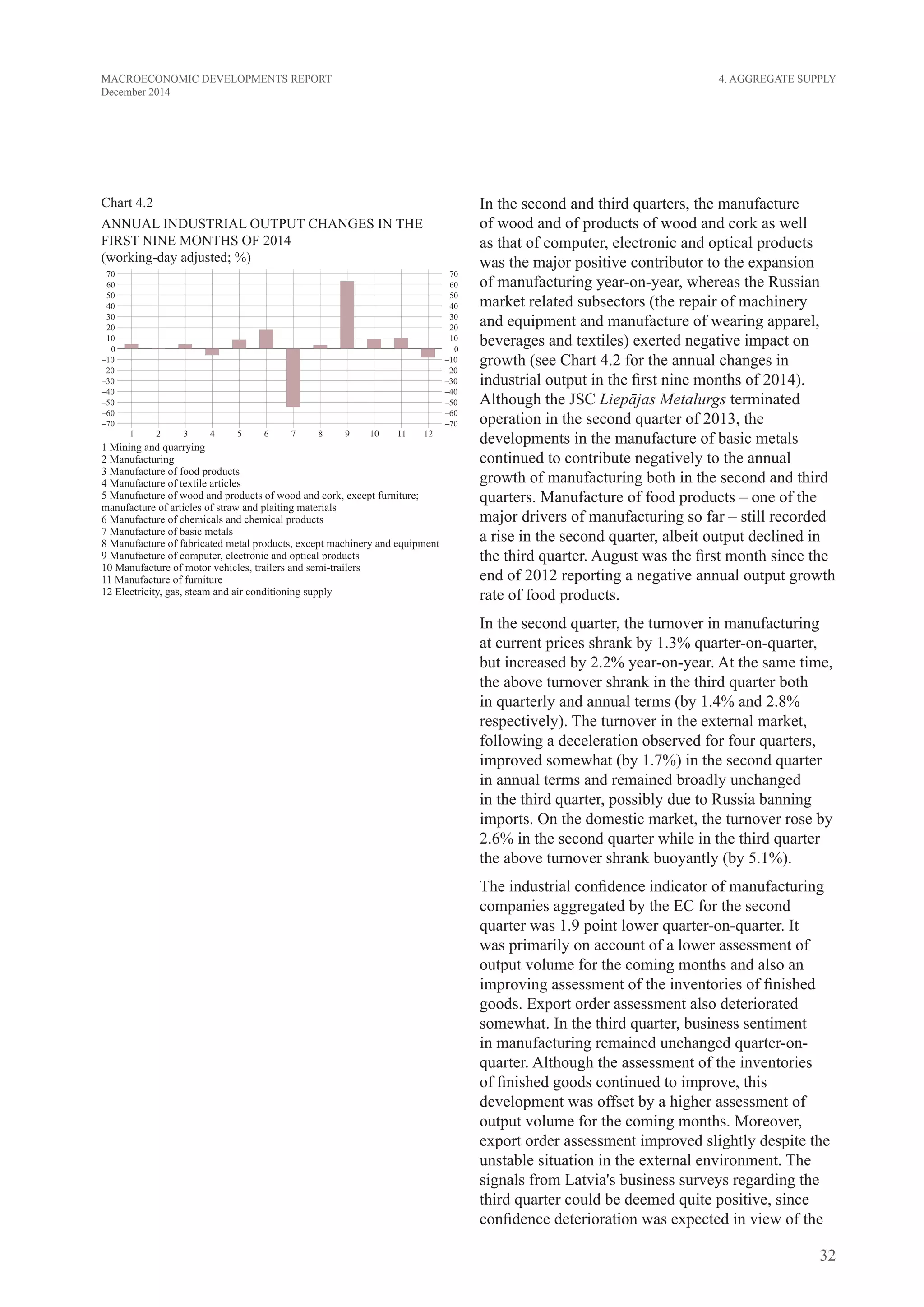

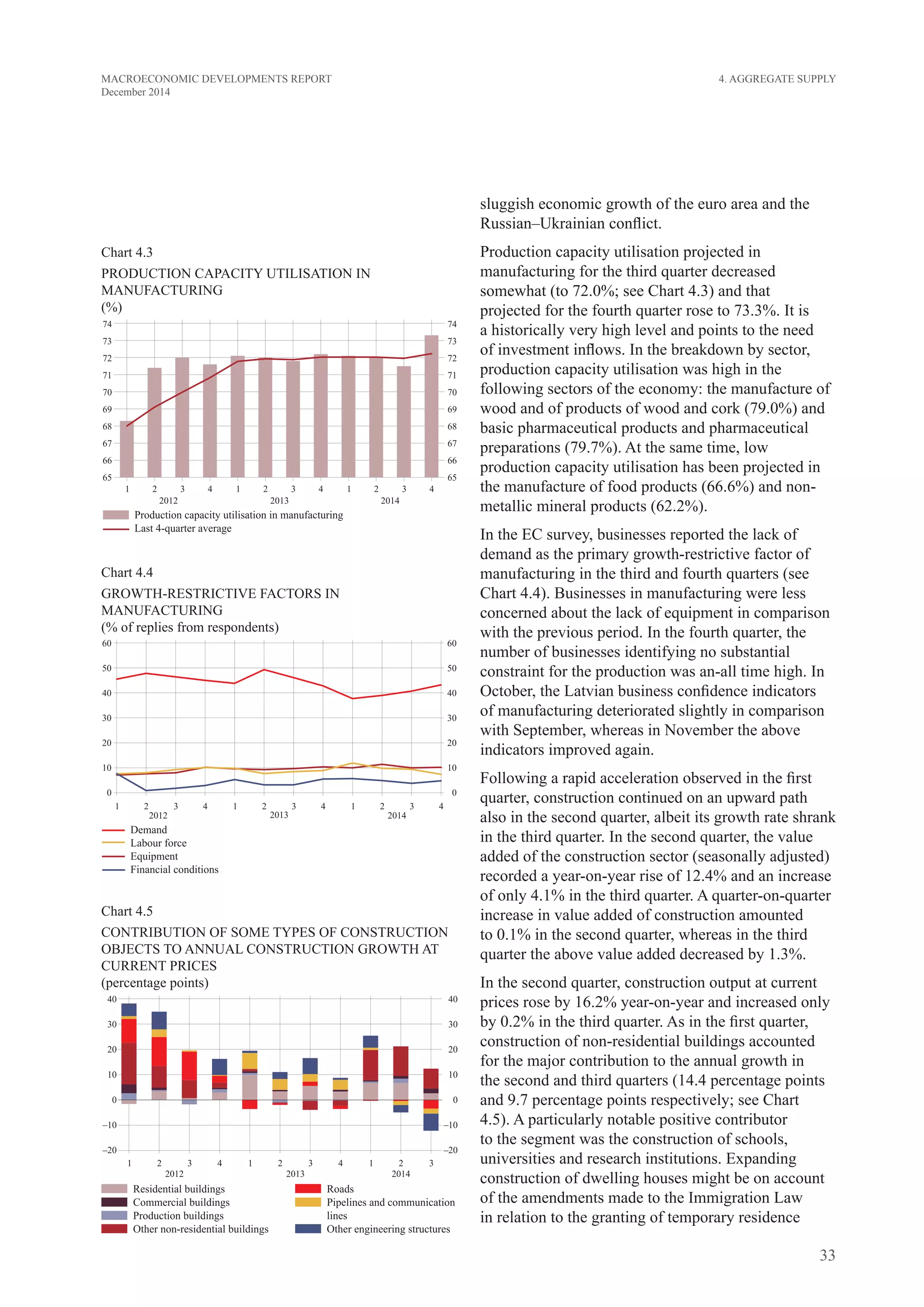

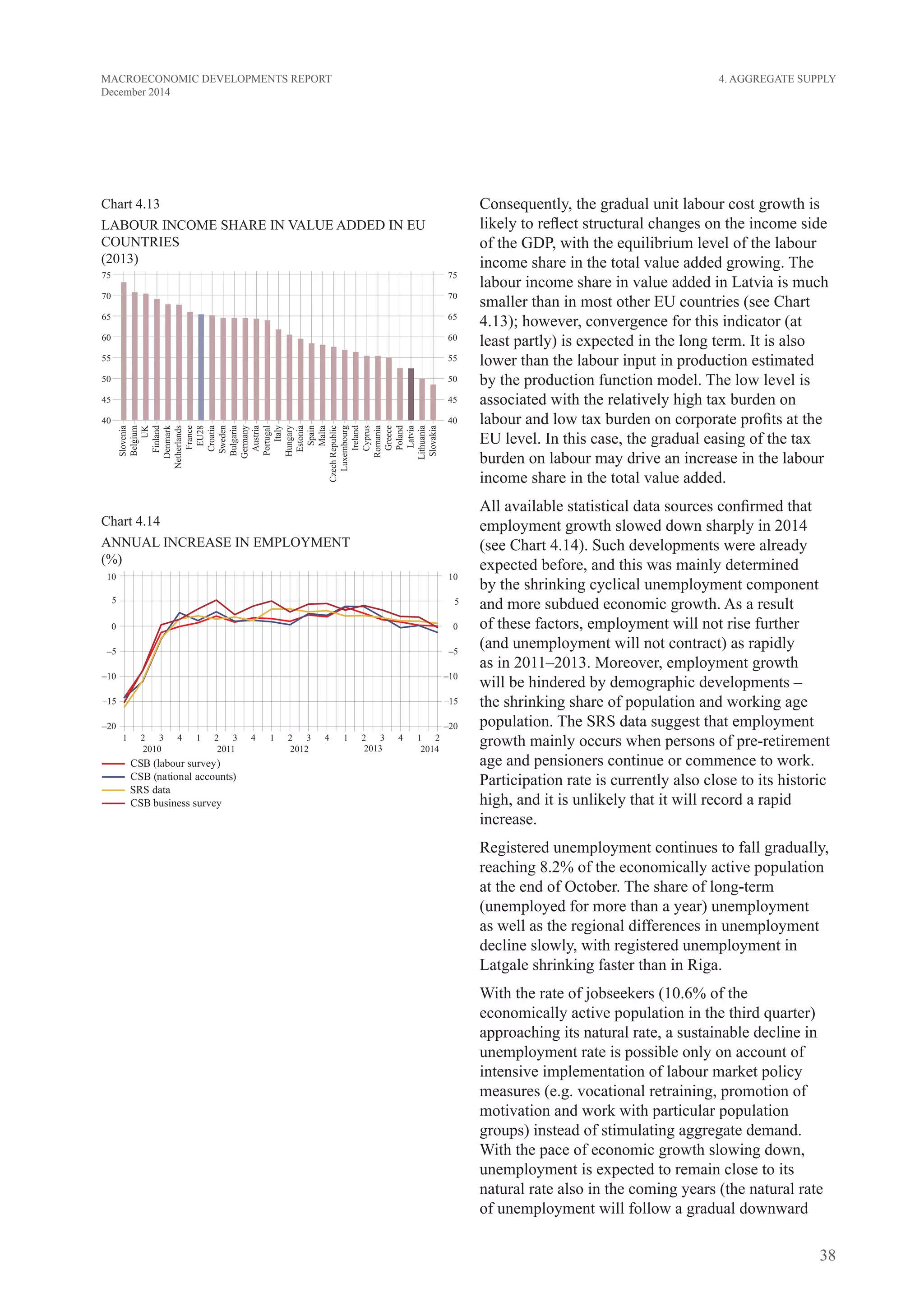

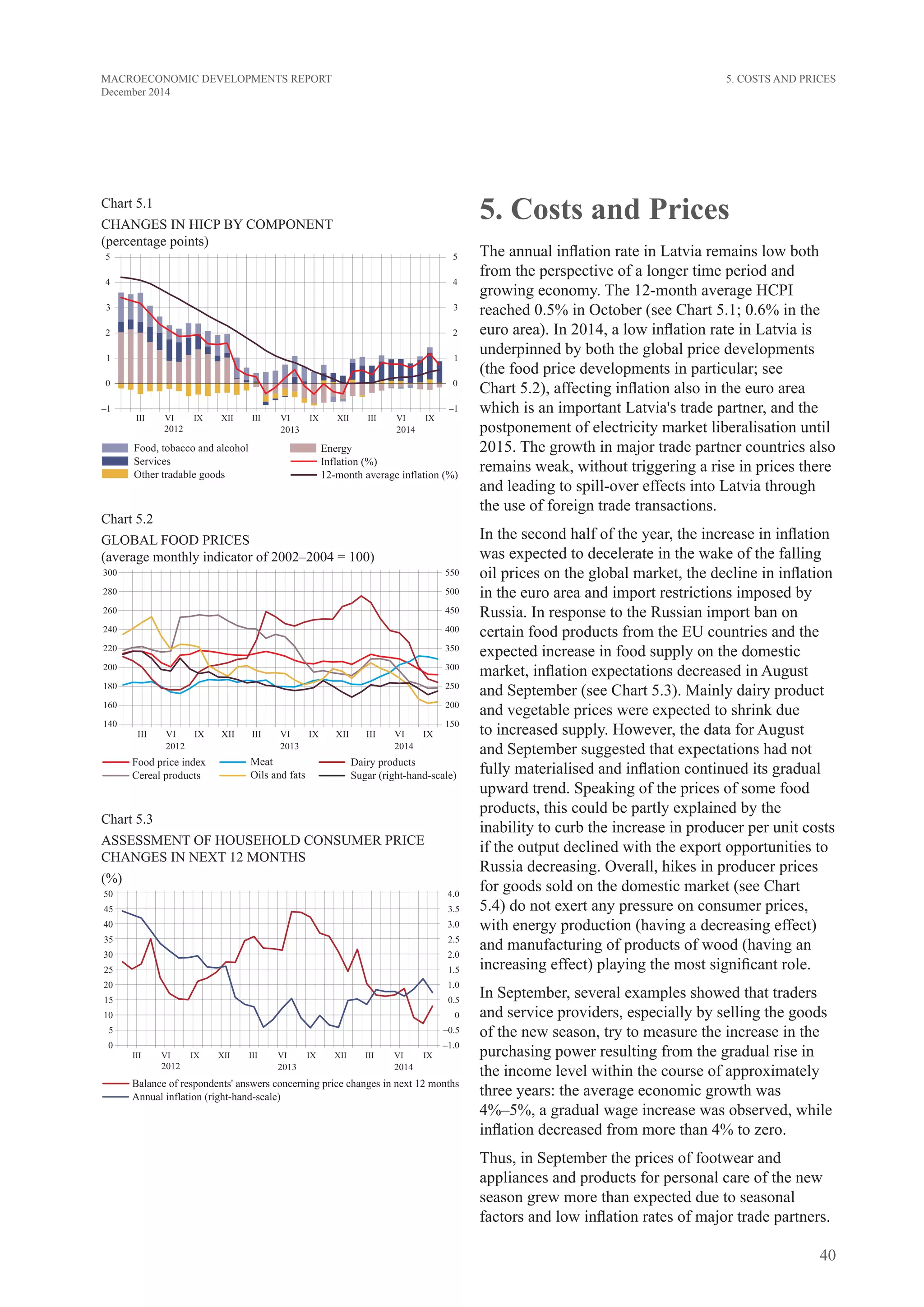

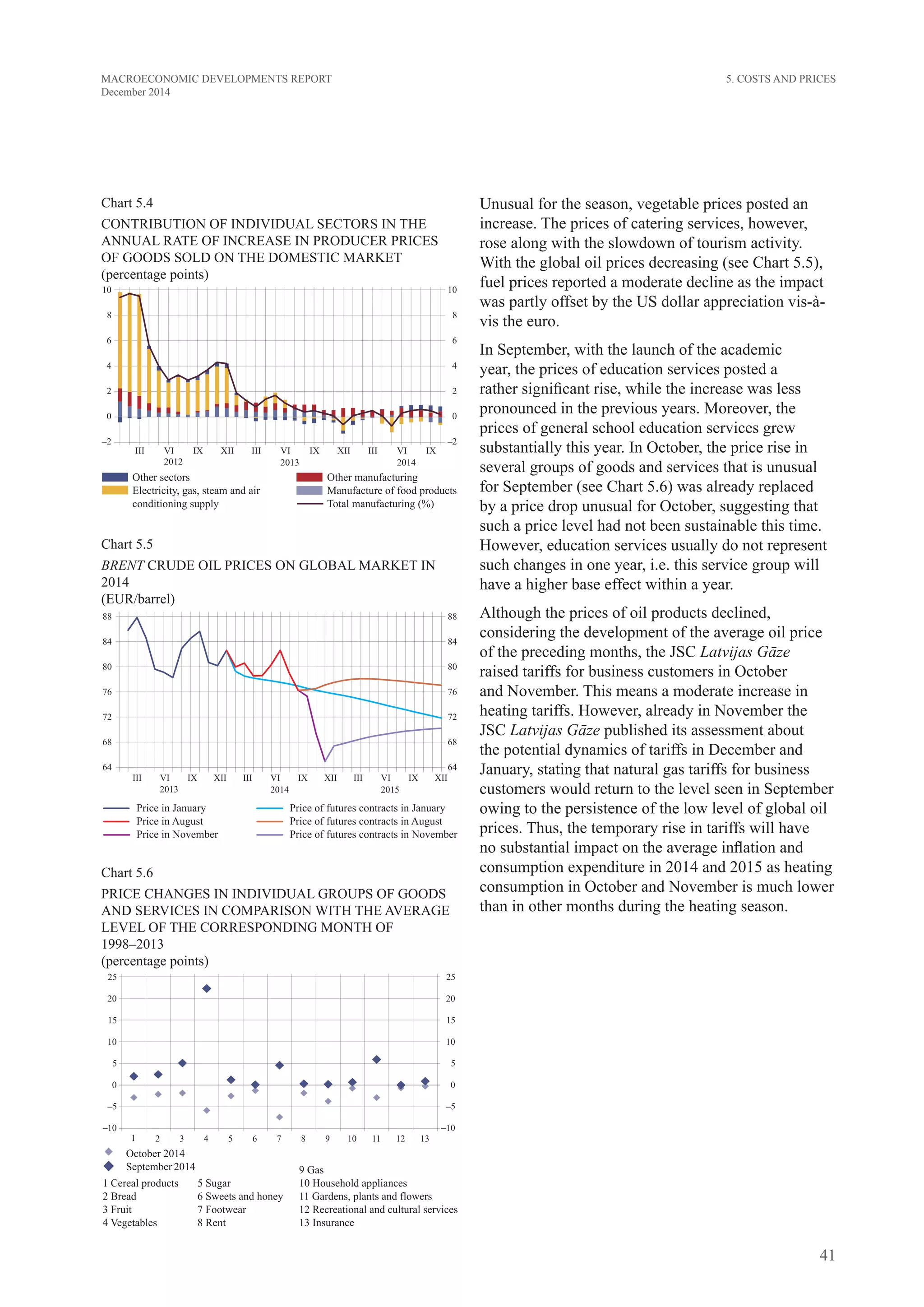

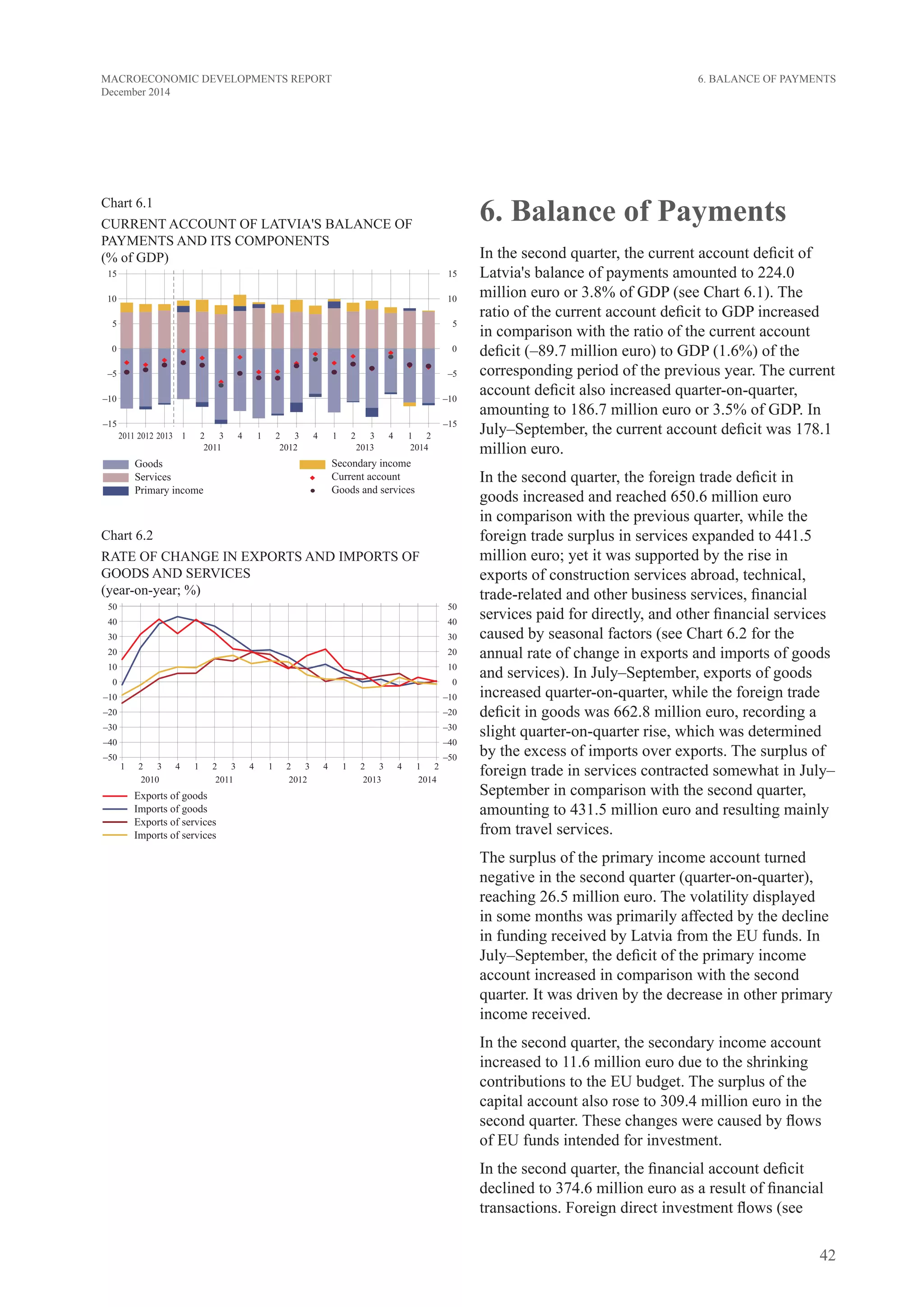

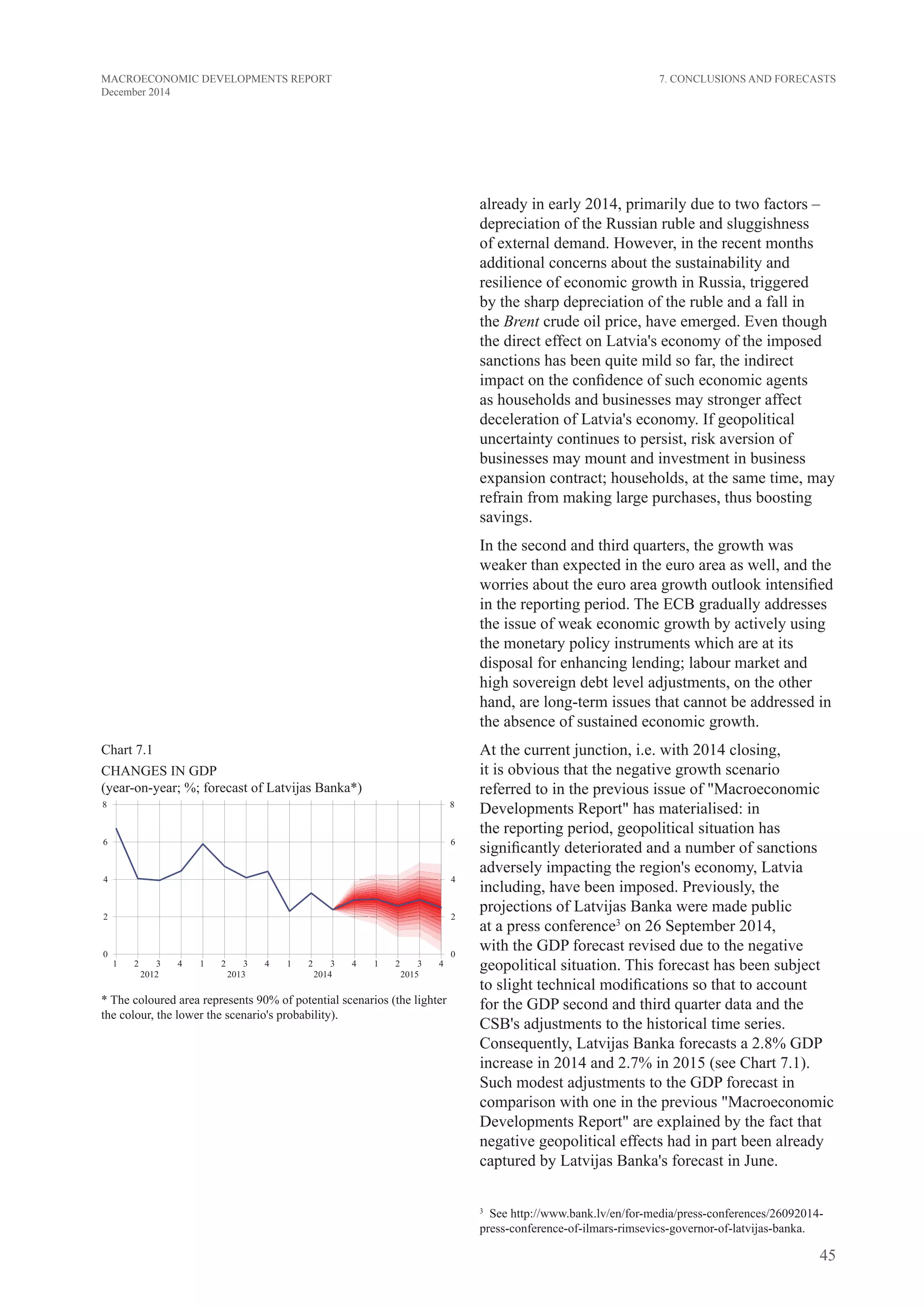

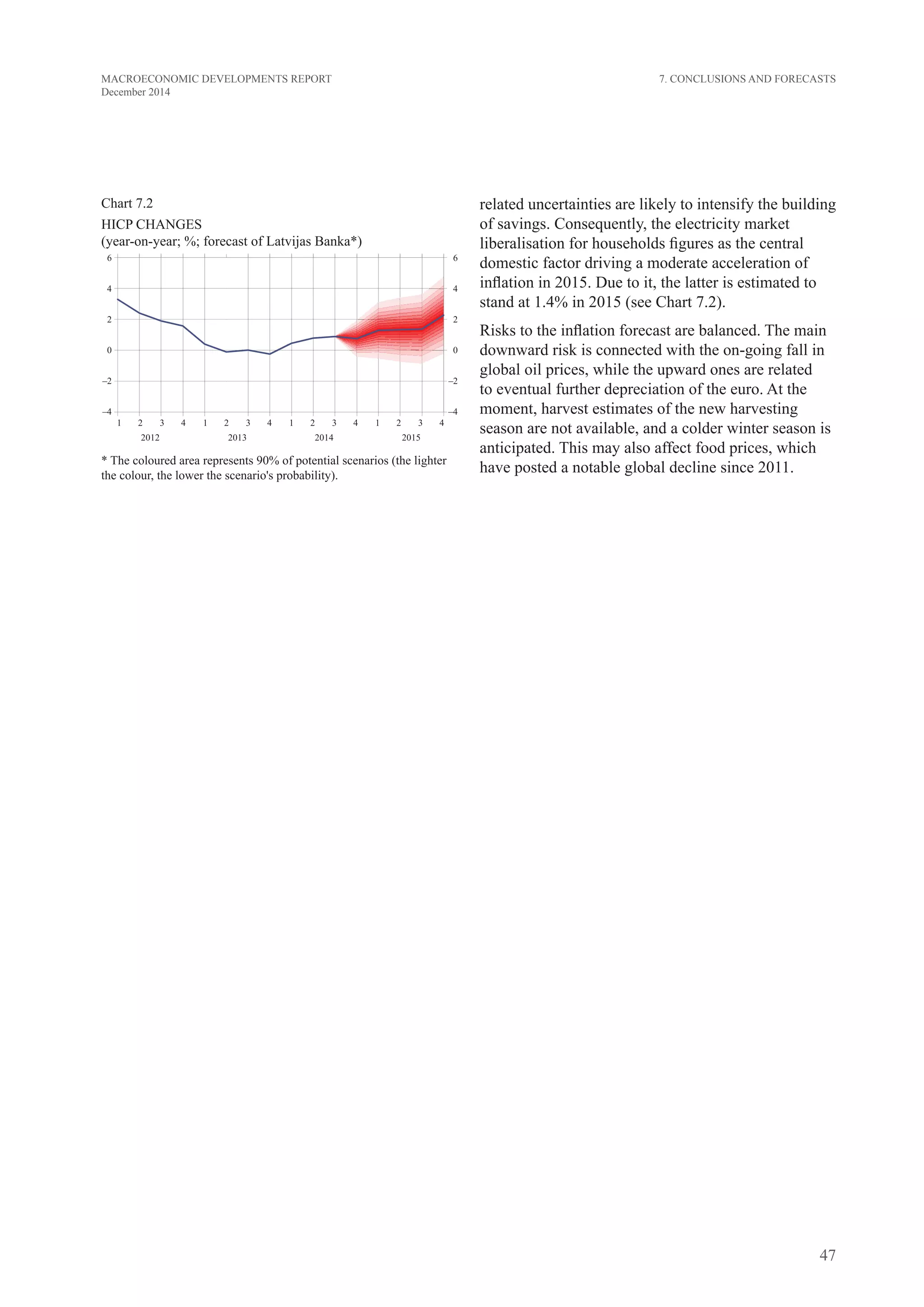

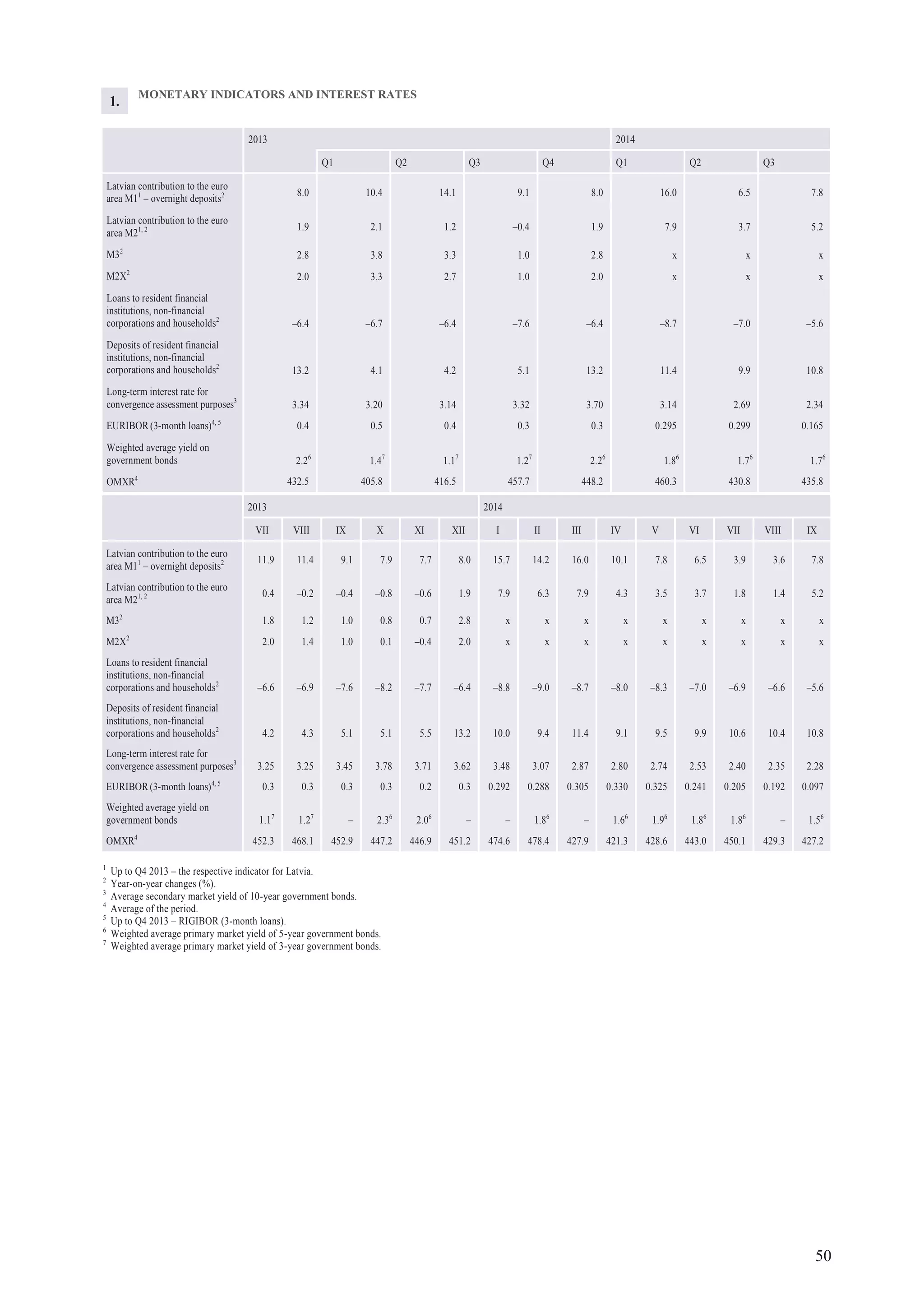

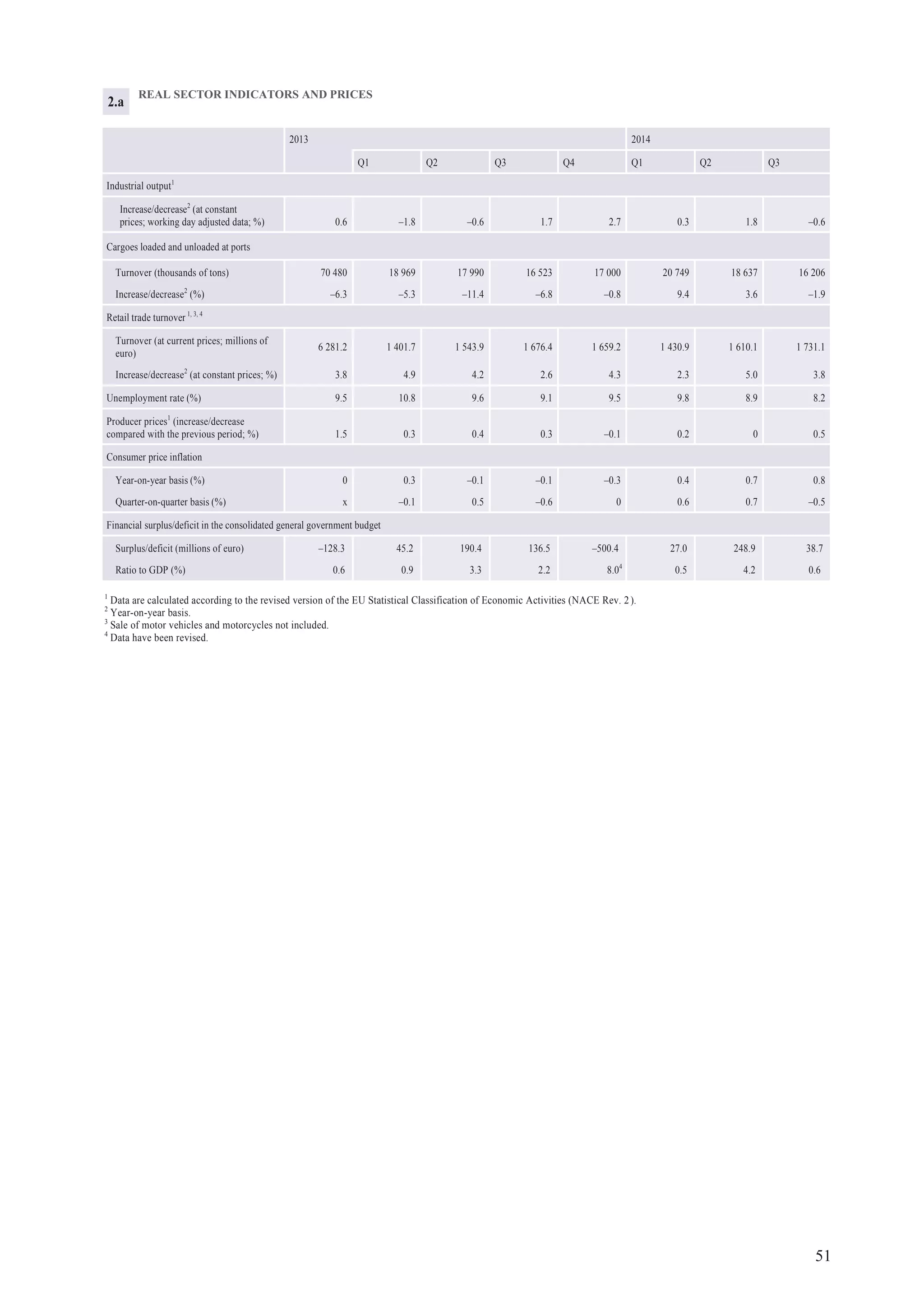

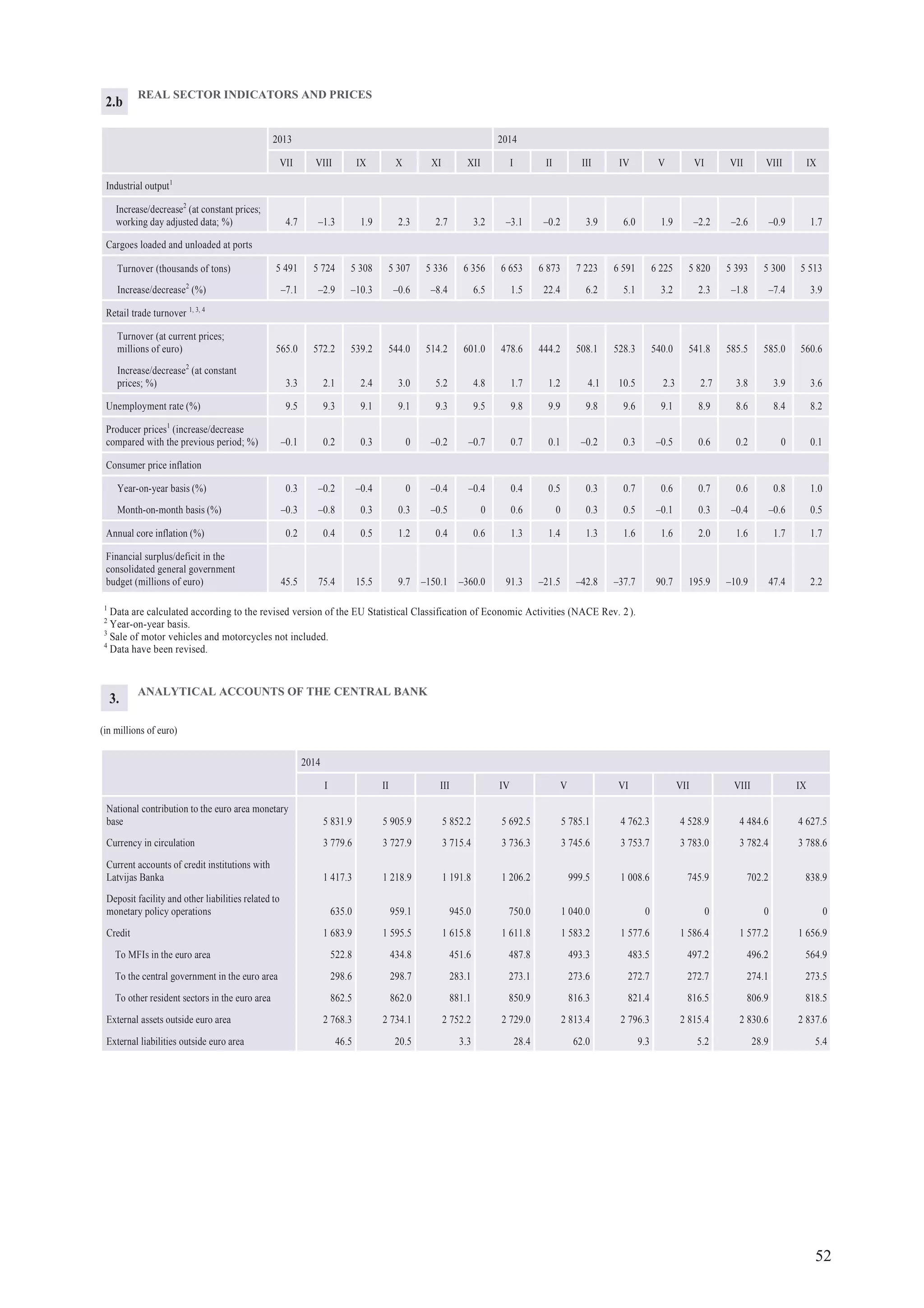

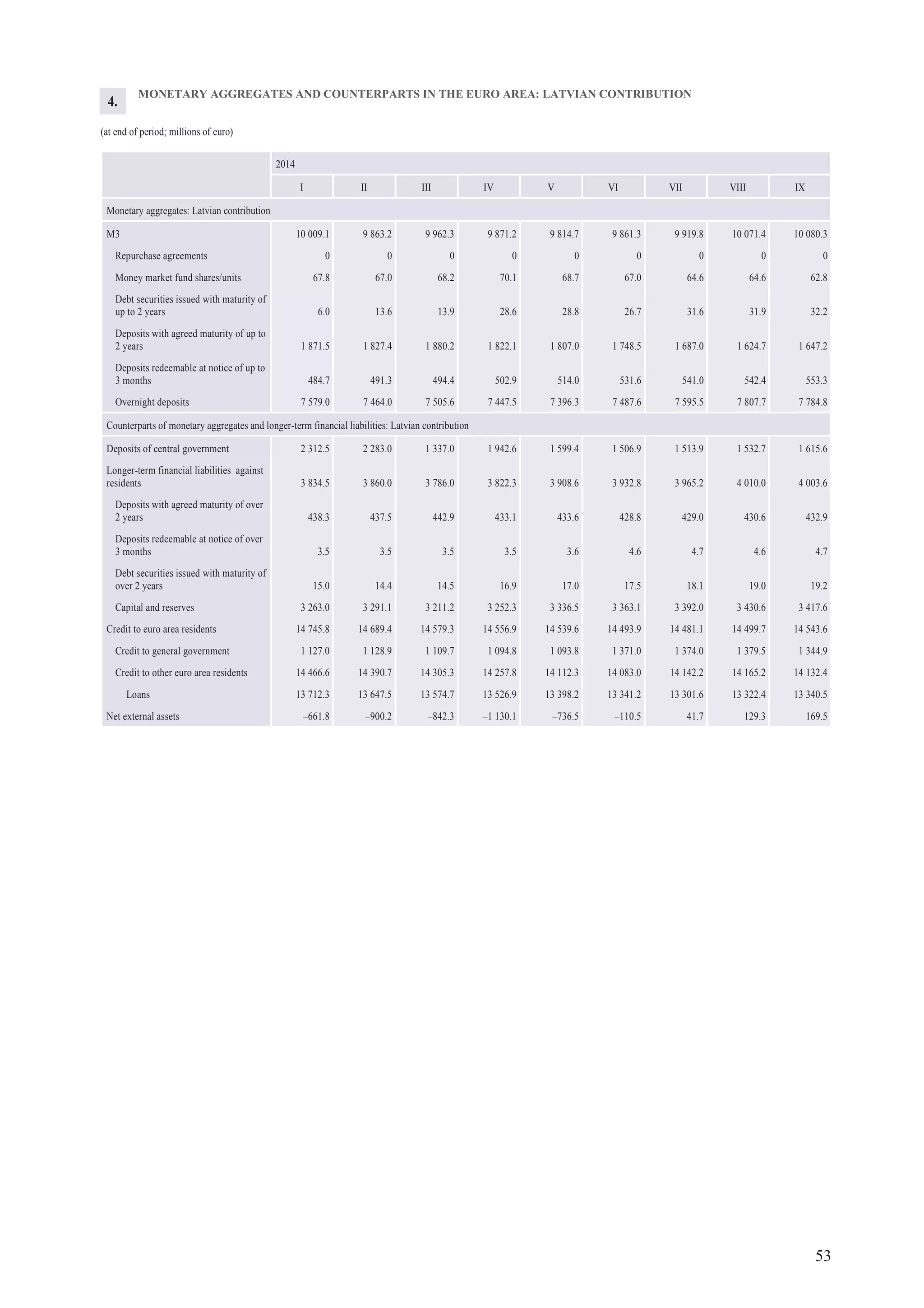

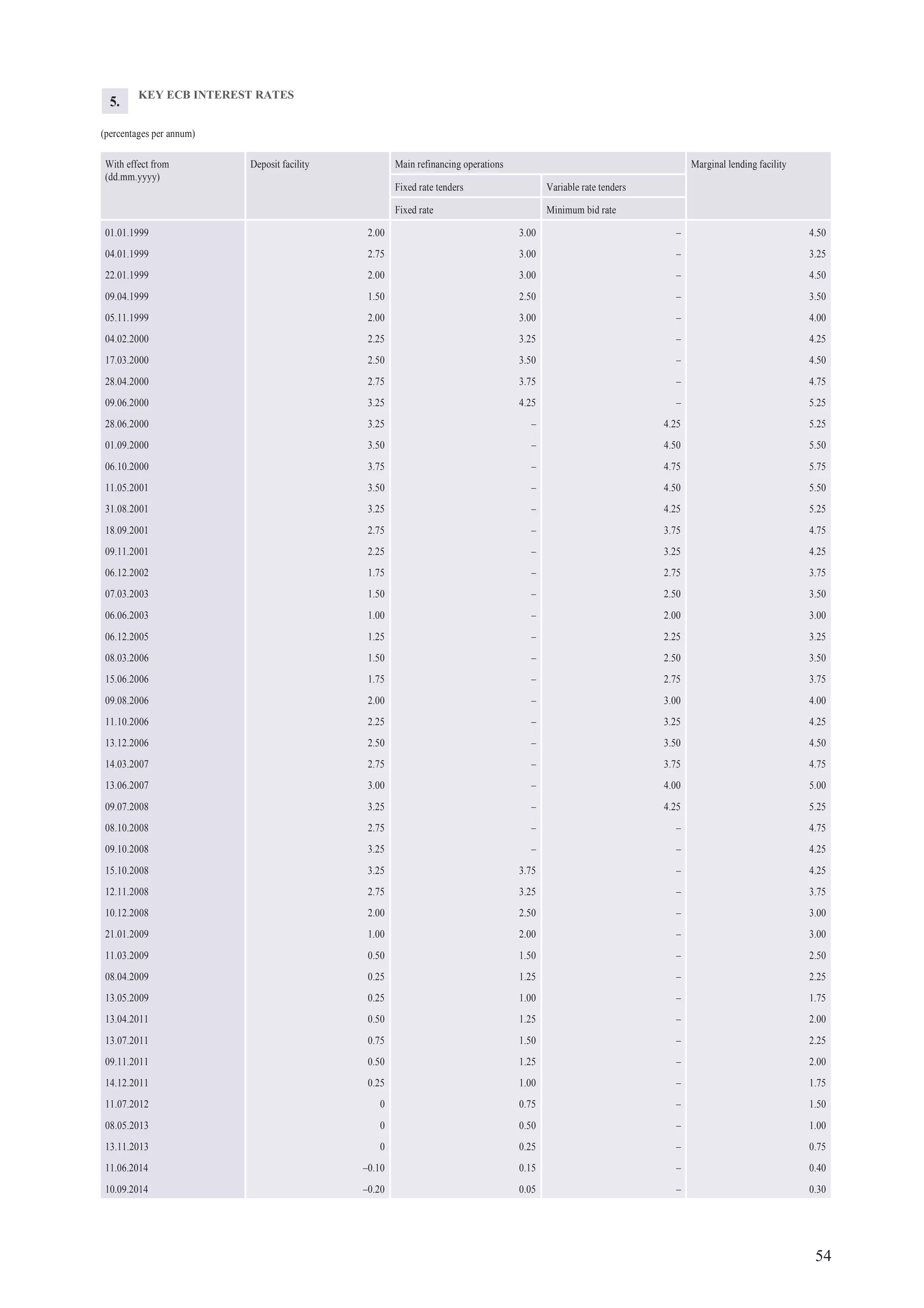

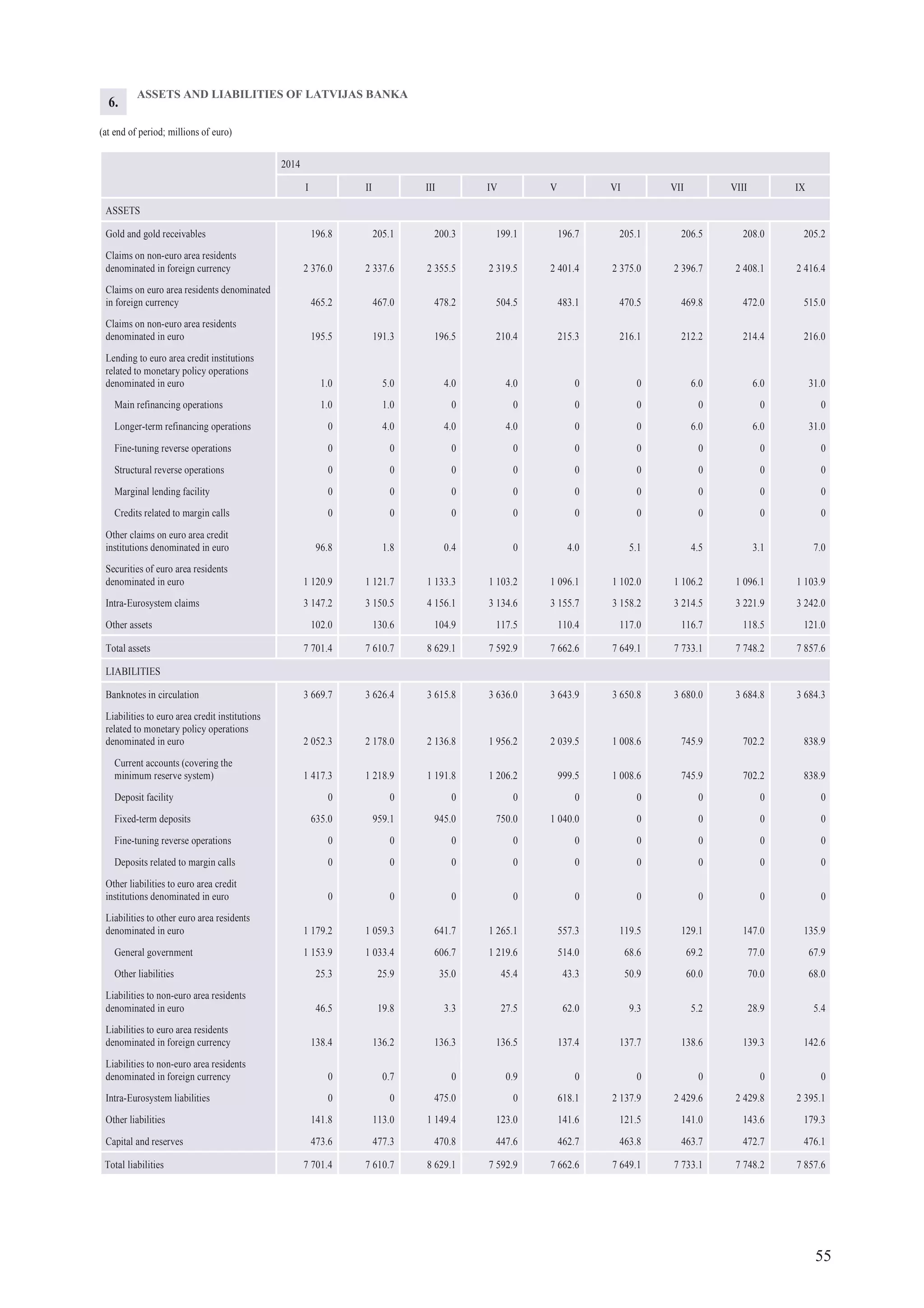

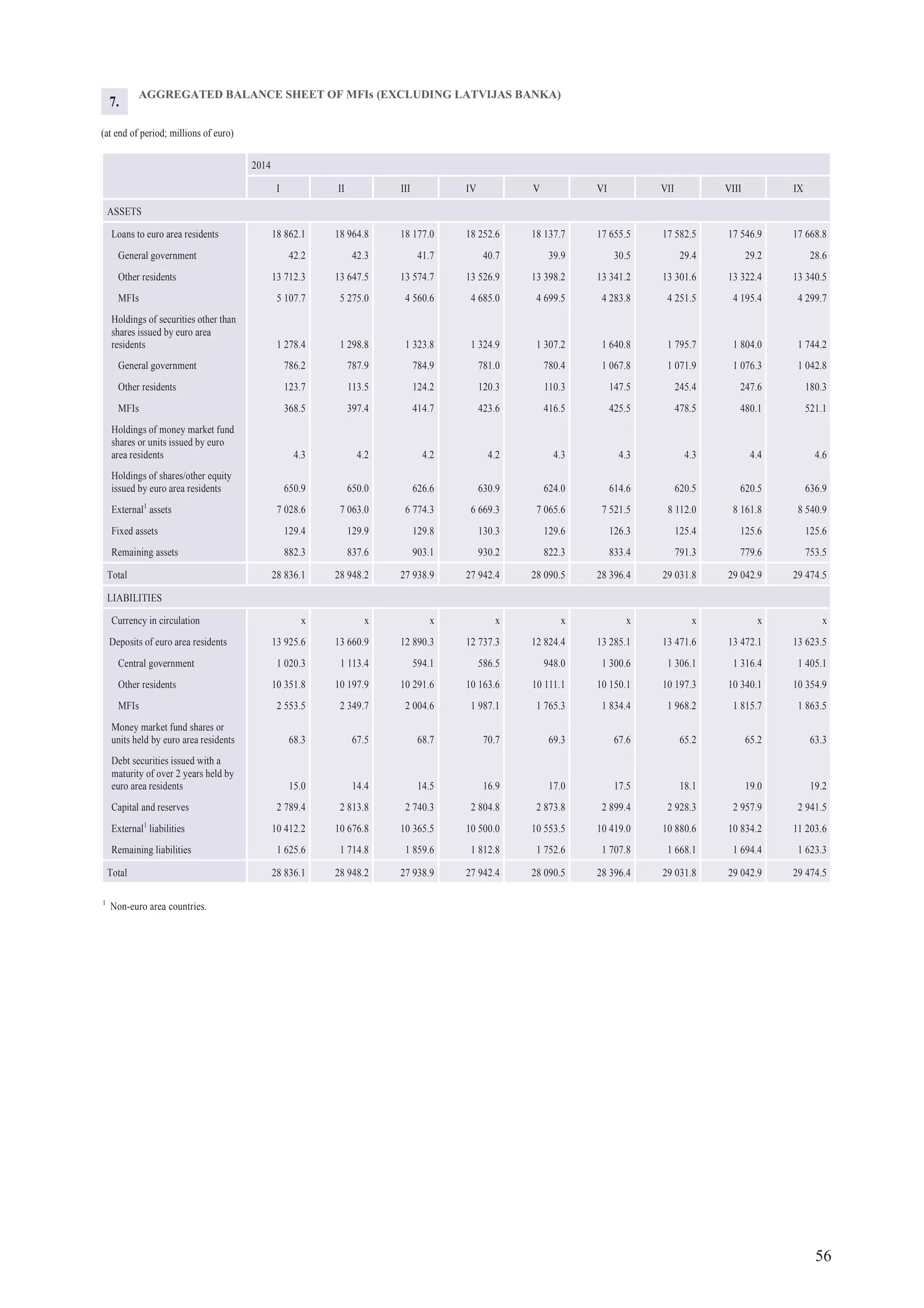

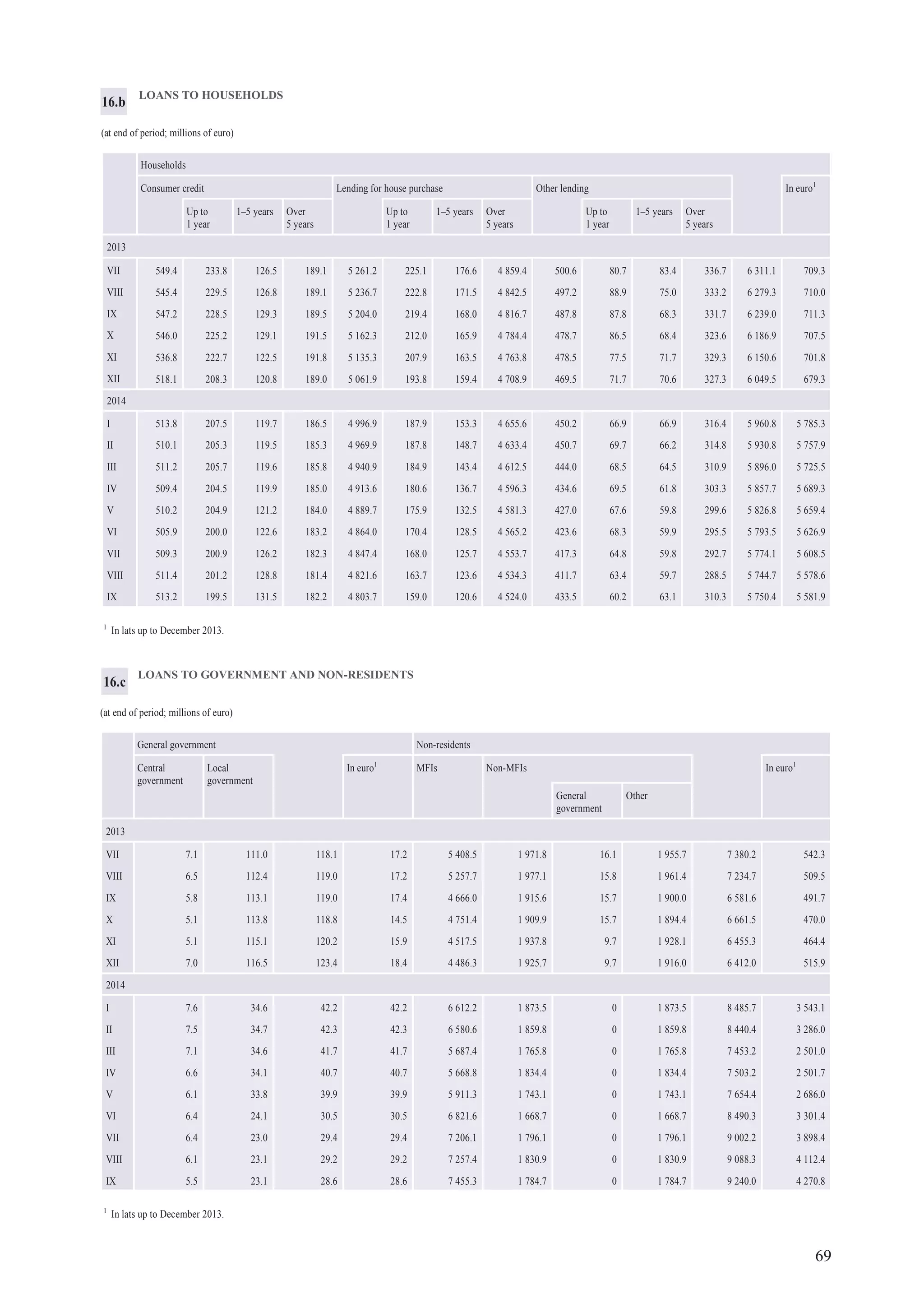

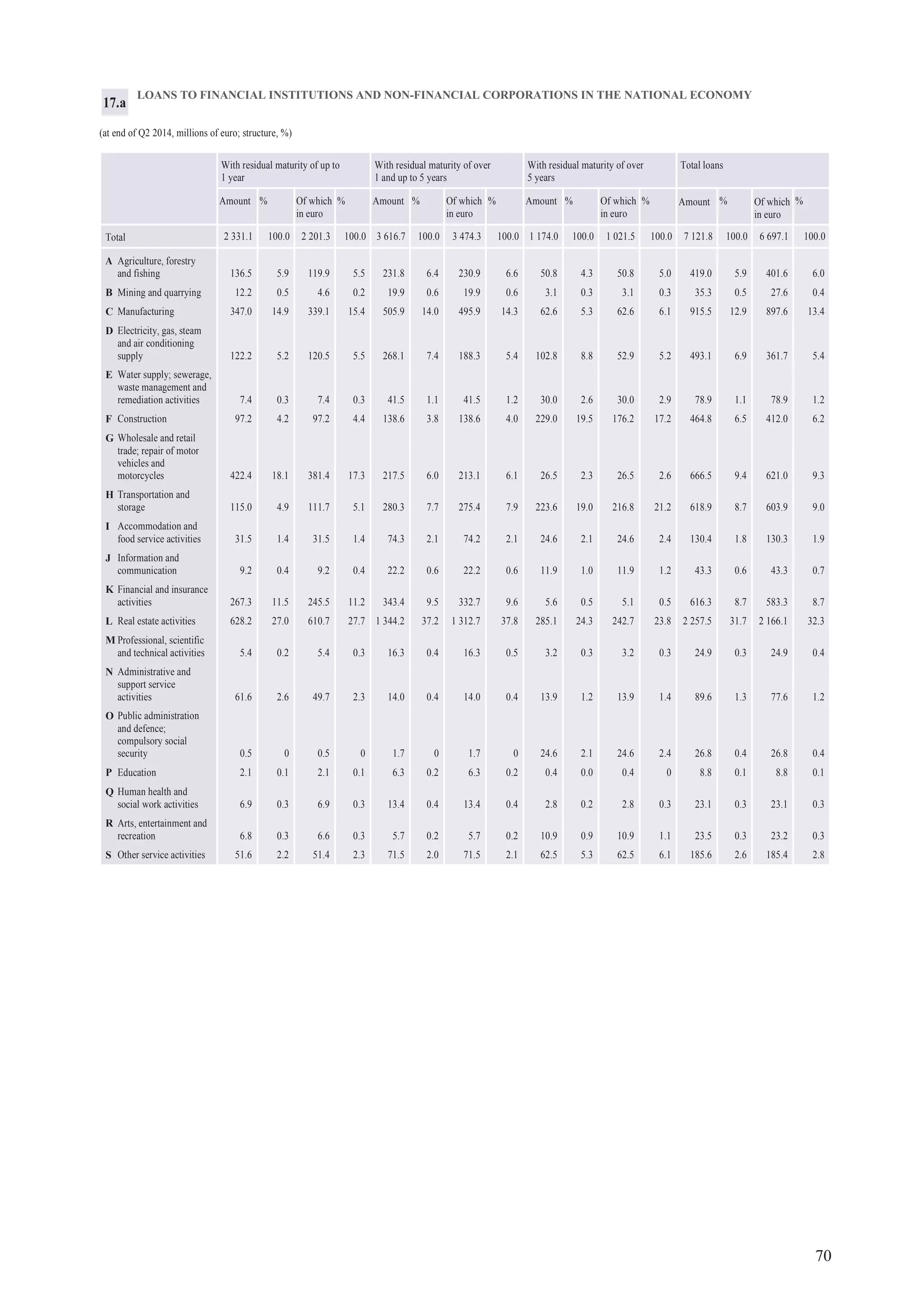

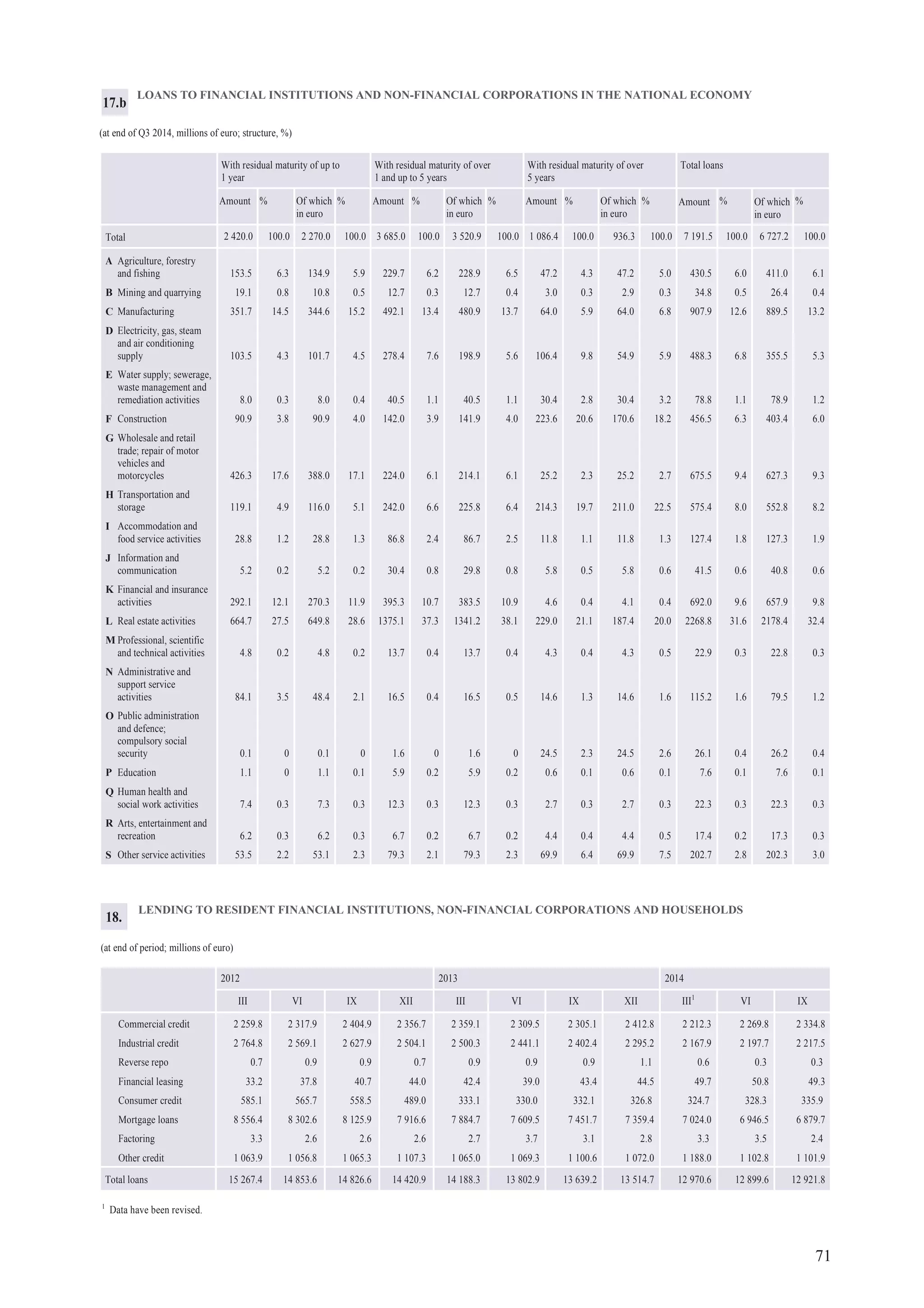

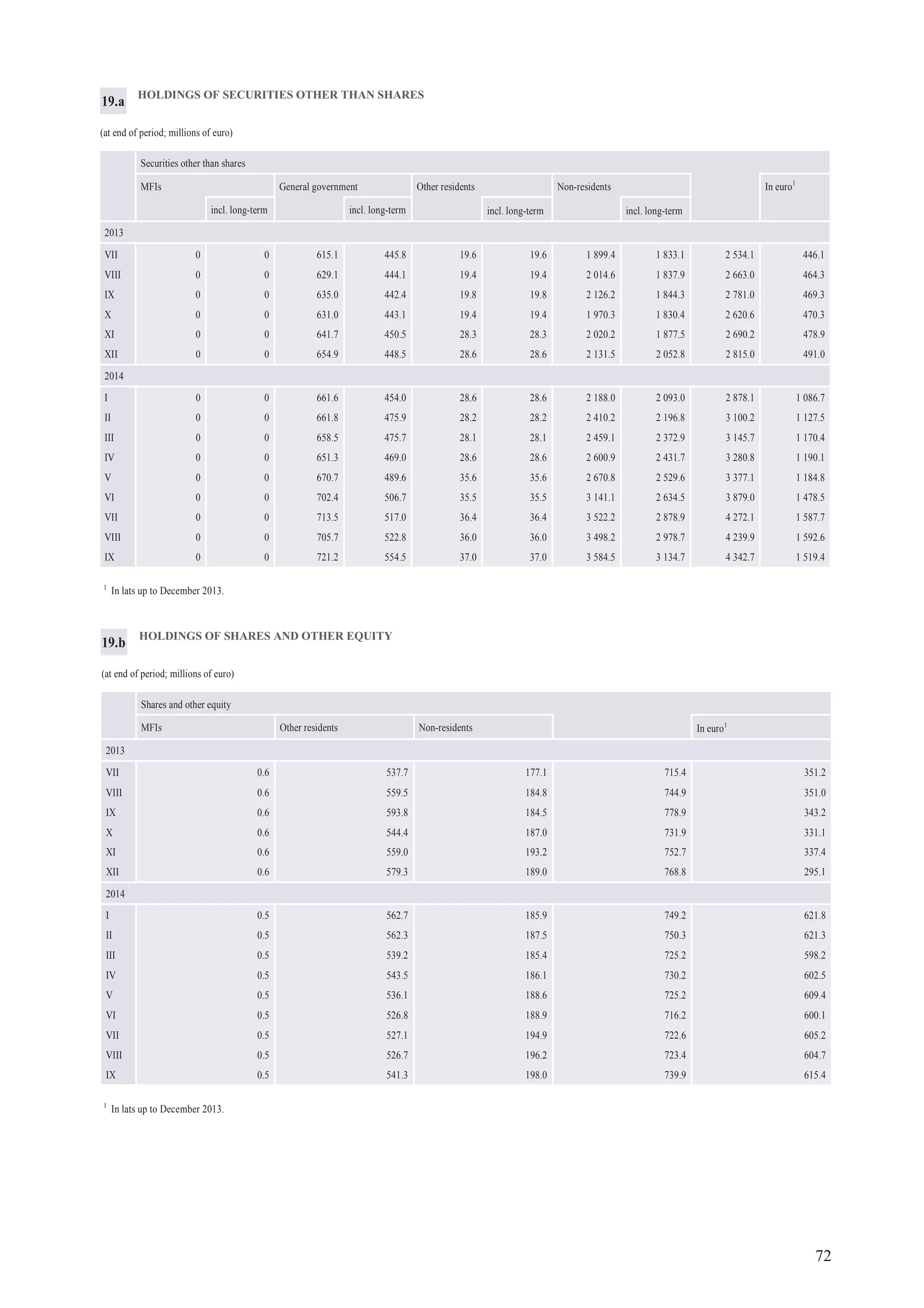

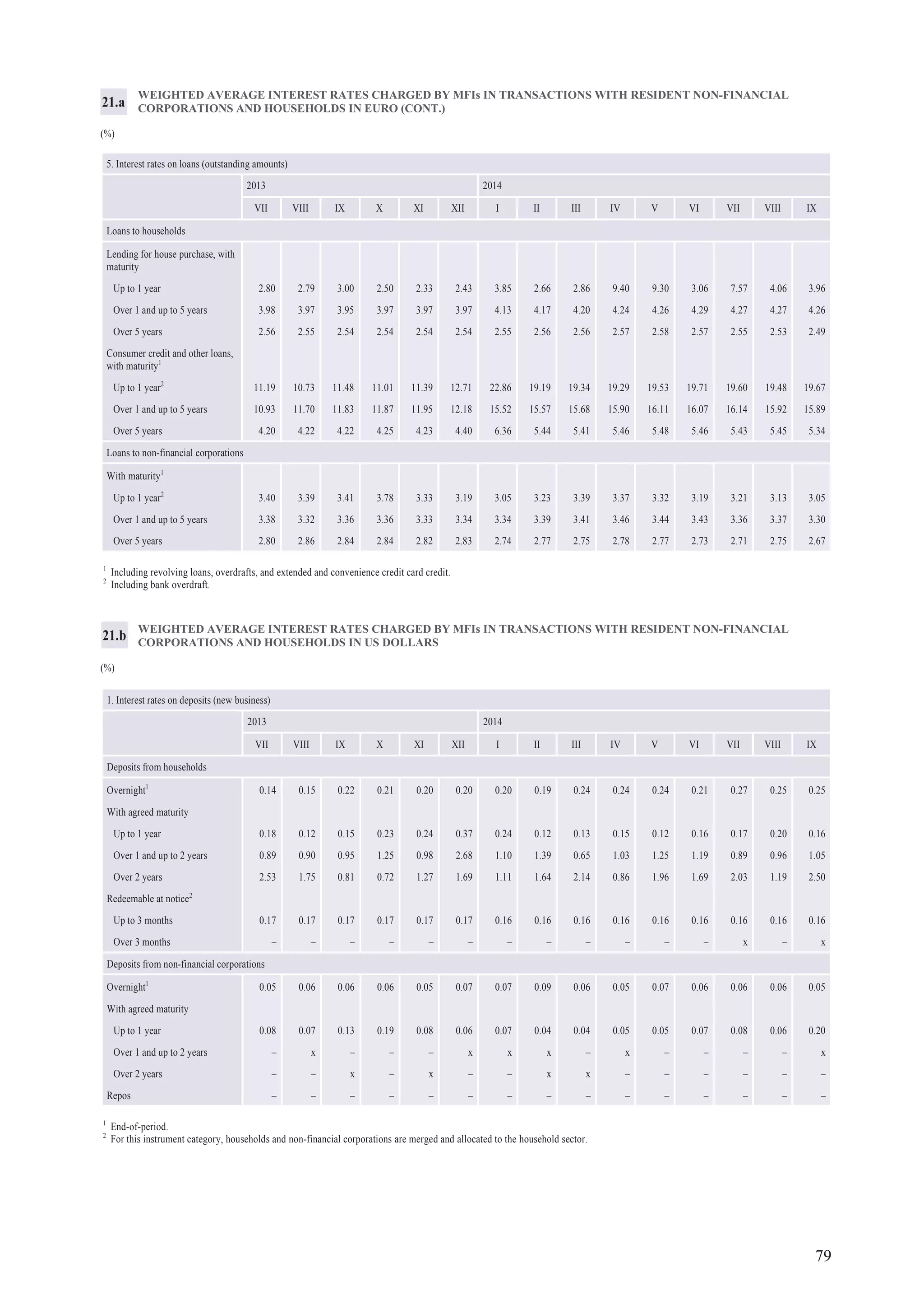

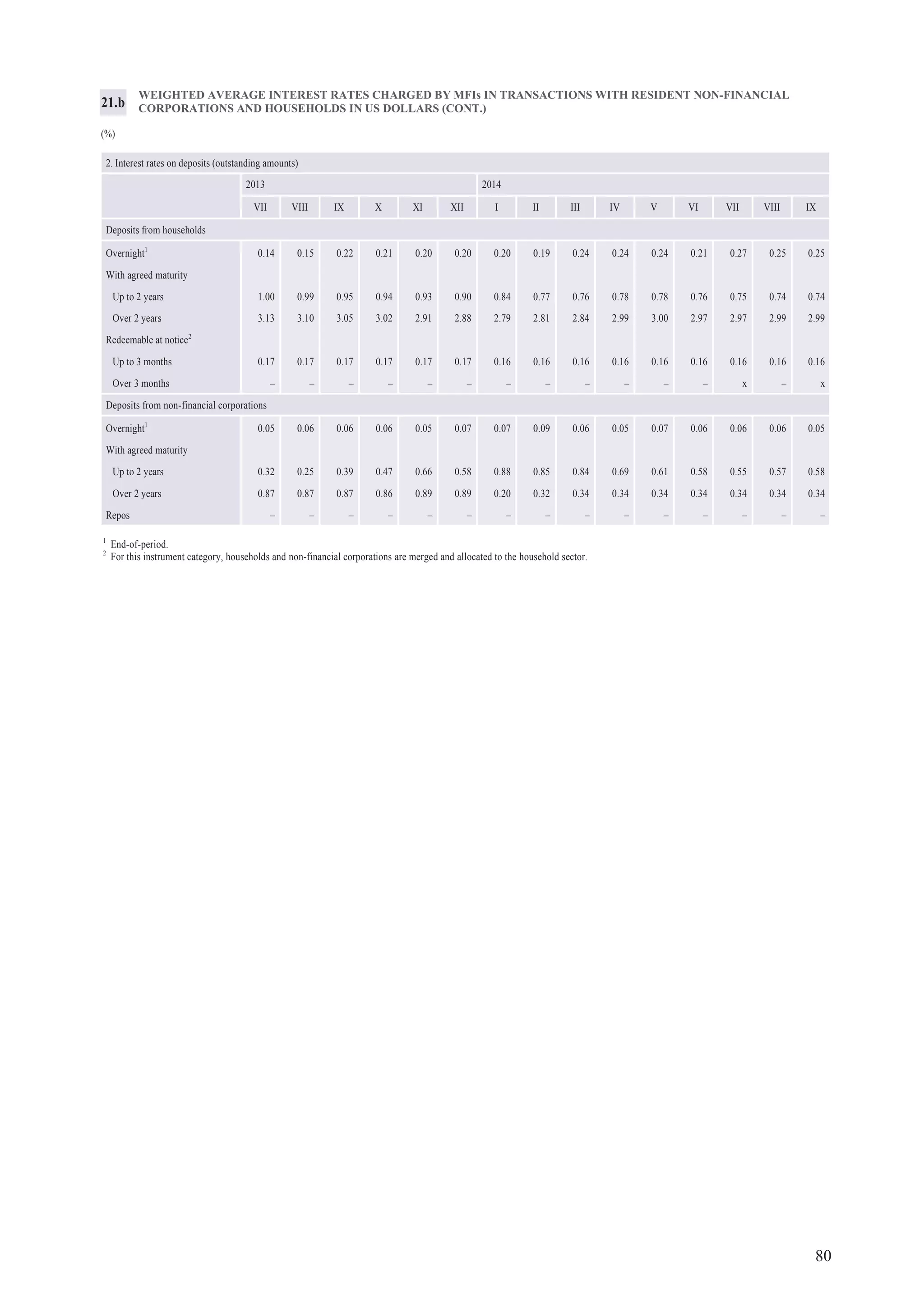

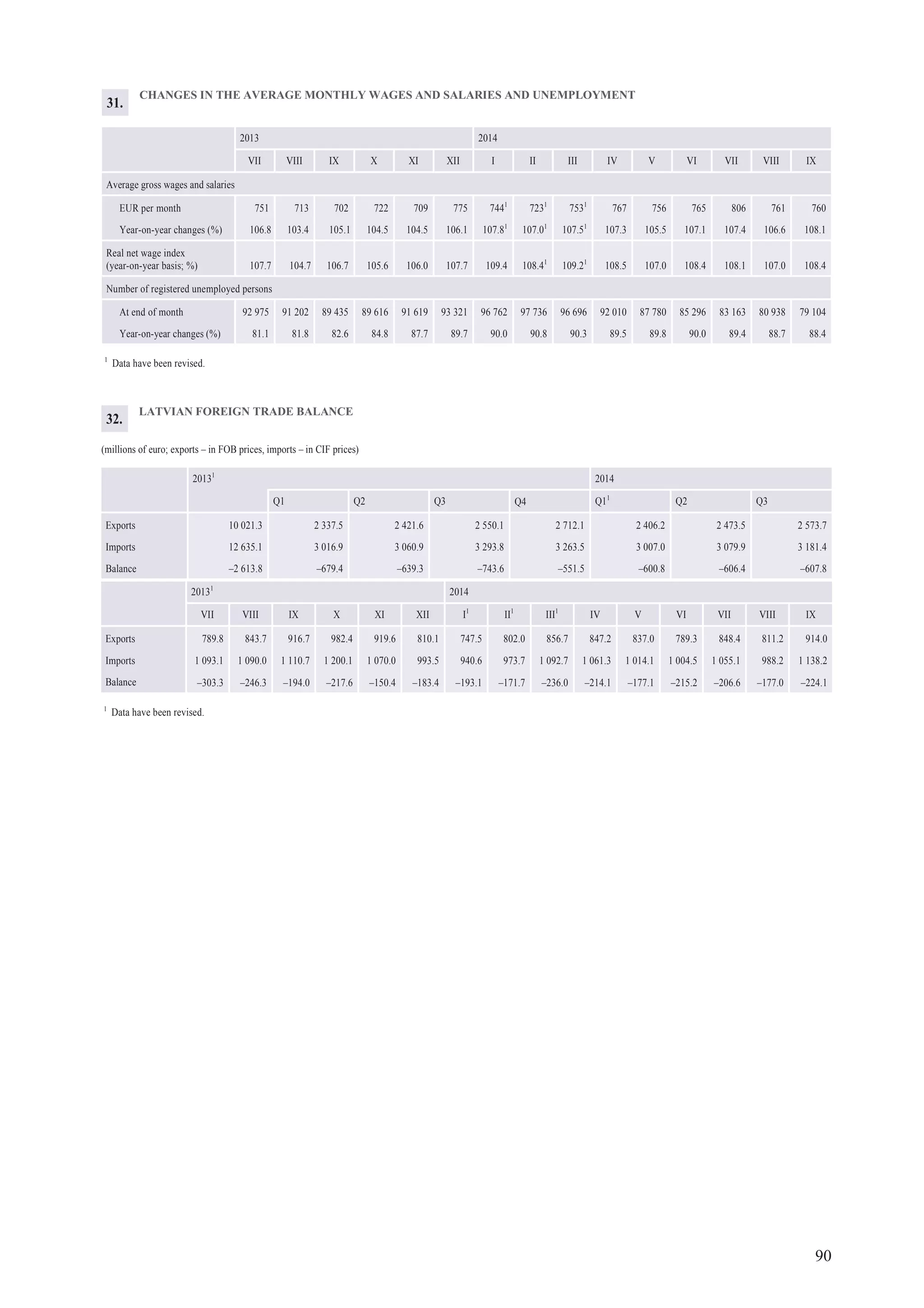

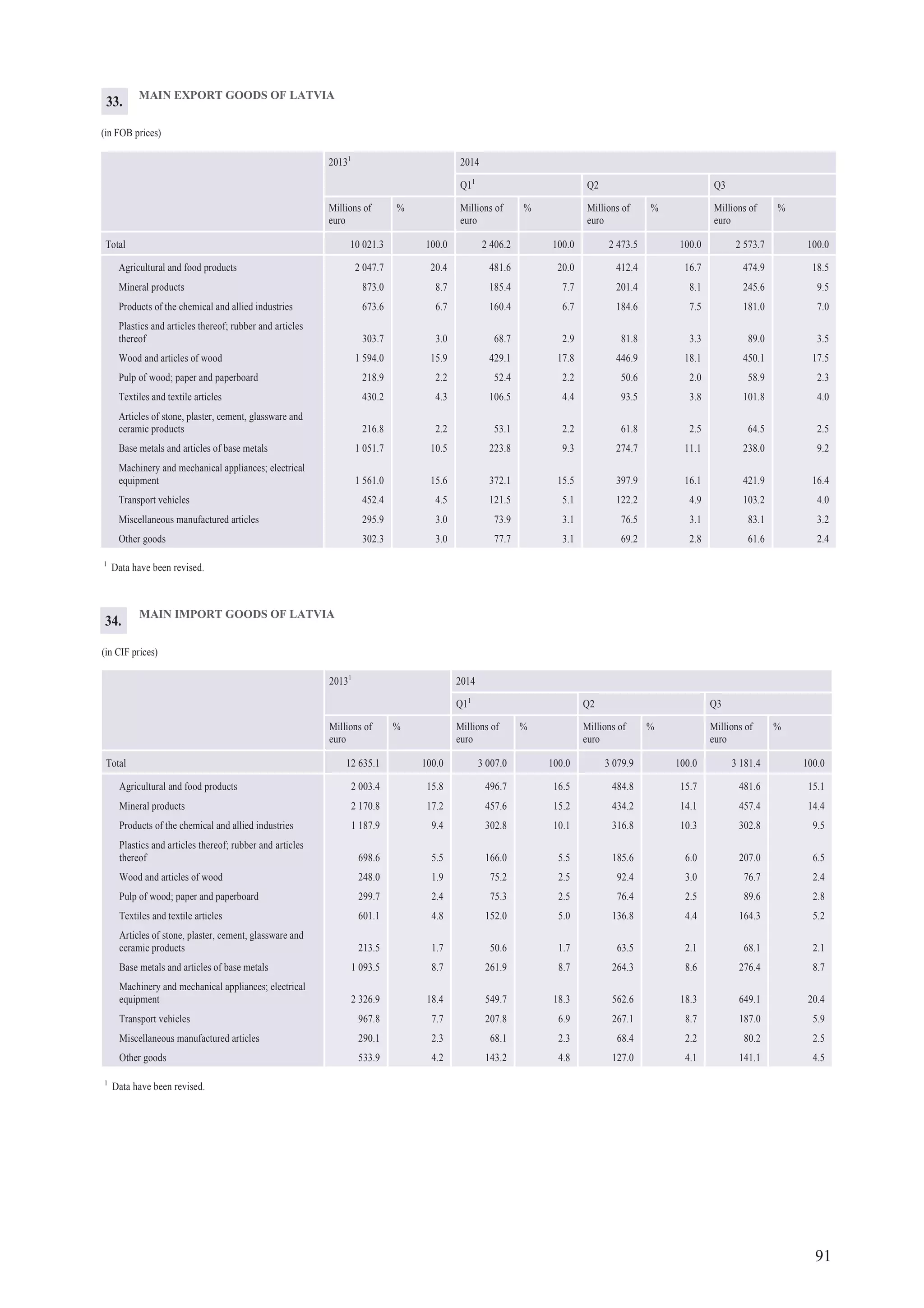

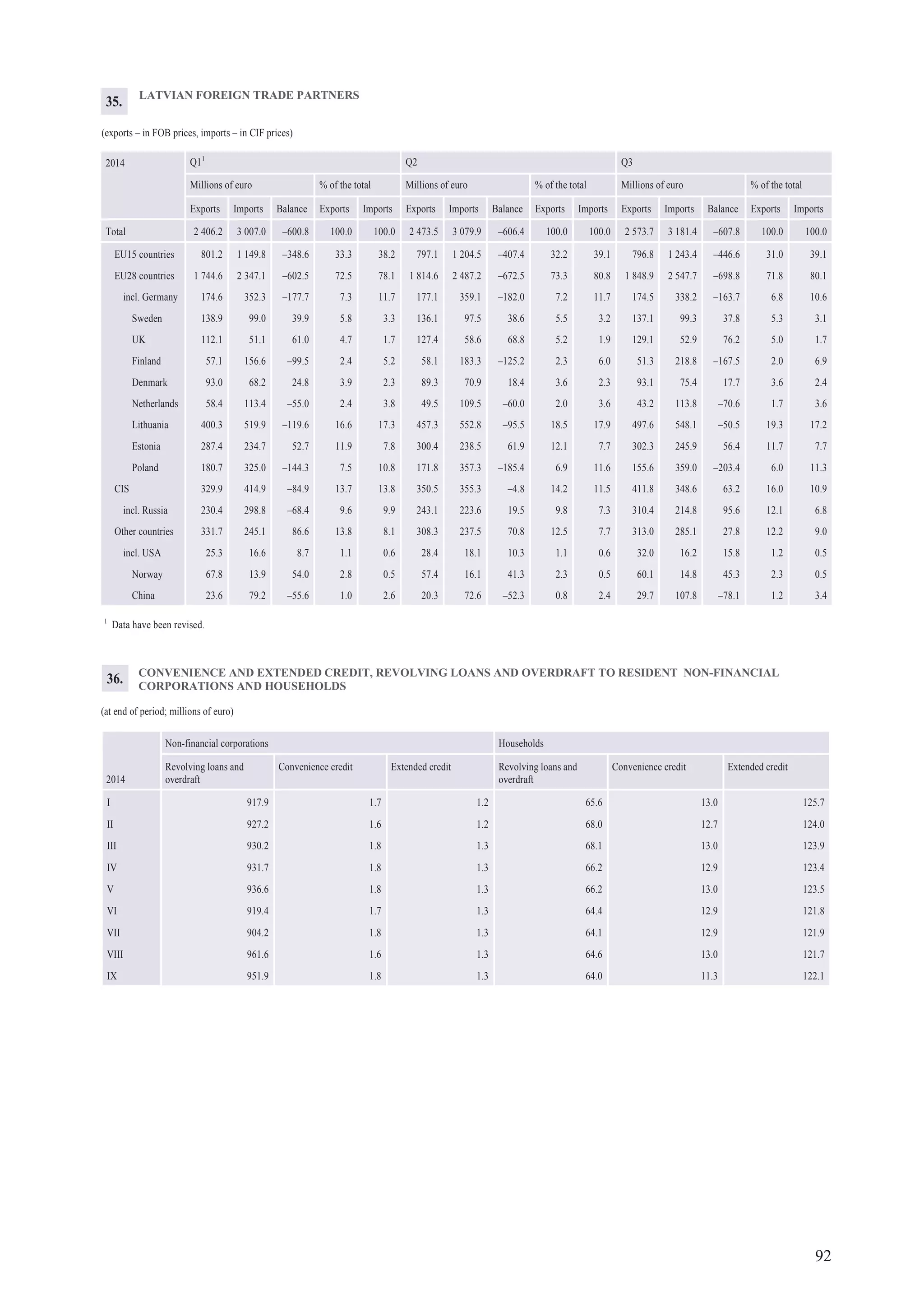

The document summarizes macroeconomic developments in December 2014. It reports that growth was weak in many of Latvia's major trade partners in late 2014. The IMF lowered GDP growth projections for the Eurozone, Germany, Sweden, Estonia and Lithuania for 2014 and 2015. Latvia's exports to Russia declined in the first nine months of 2014, though exports to other countries increased. The ECB lowered interest rates and implemented new bond purchase programs to stimulate lending and the Eurozone economy. Latvian lending continued a slow downward trend in late 2014 despite ECB actions. Inflation in Latvia remained low at 0.5% in October 2014.