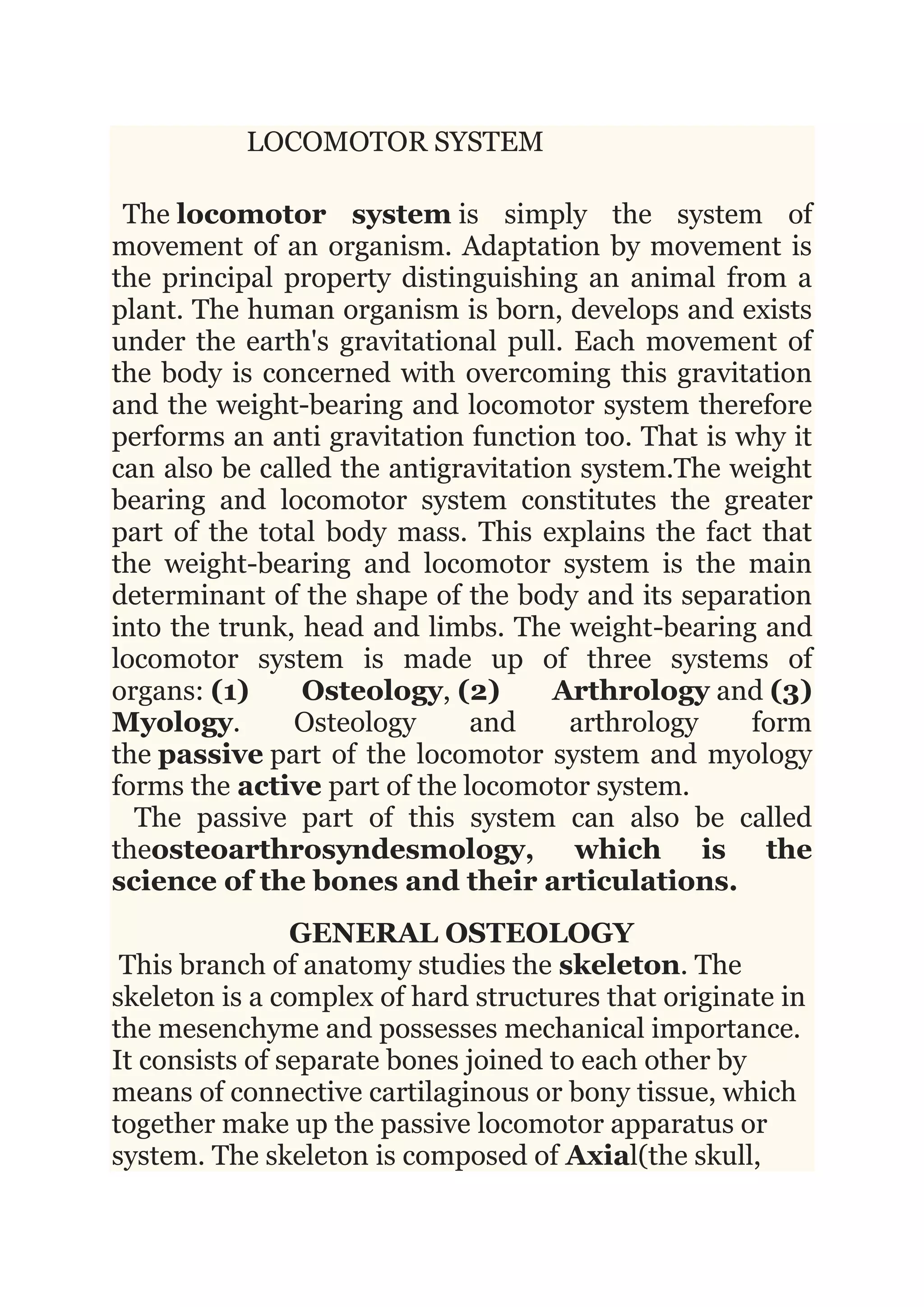

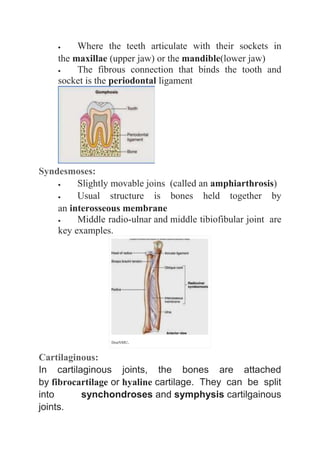

The document summarizes the three main systems that make up the human locomotor system: osteology, arthrology, and myology. Osteology is the study of bones and how they form the skeleton. Arthrology studies joints and their classification. Myology covers the muscular system, including muscle structure, function, and types. Together, these three systems work passively and actively to enable movement and overcome gravity.