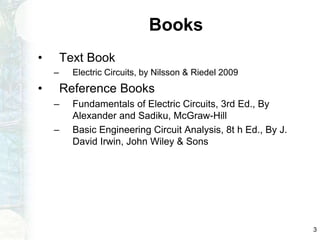

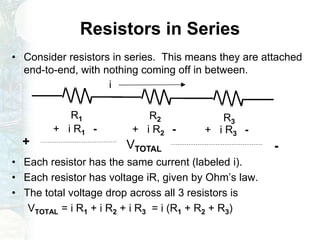

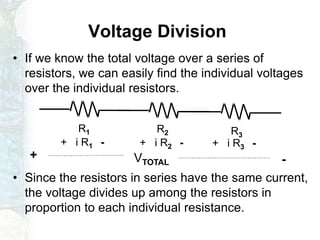

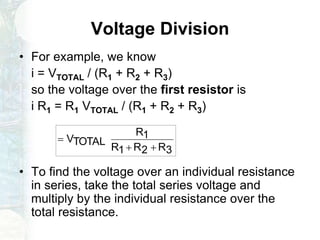

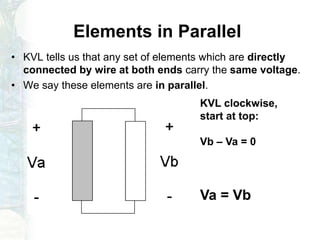

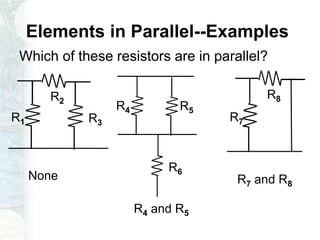

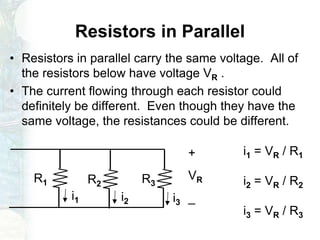

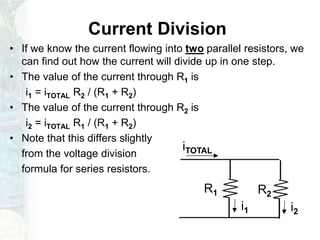

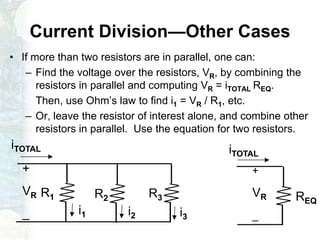

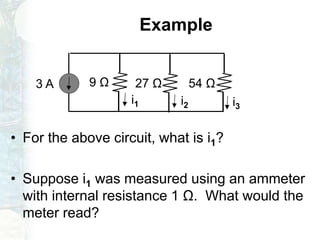

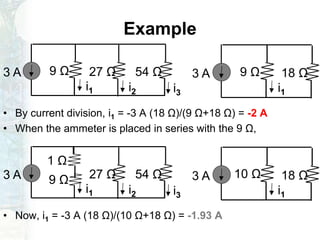

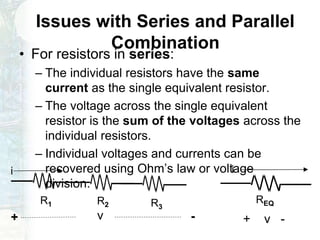

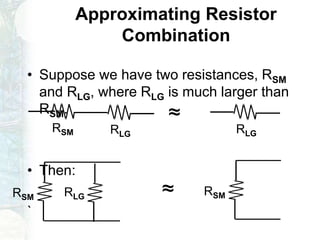

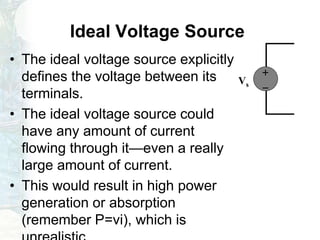

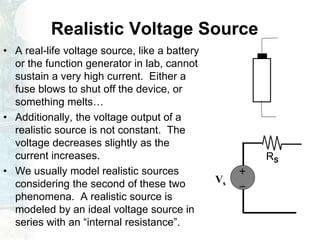

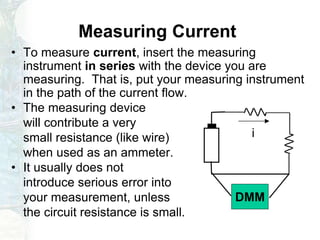

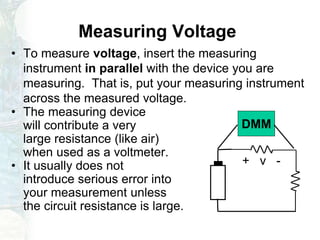

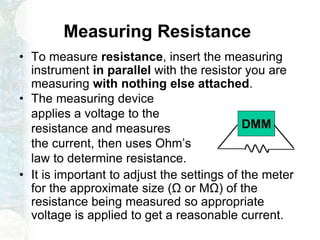

The document outlines a course on linear circuit analysis, led by Dr. Muhammad Talha Gul, including key textbooks and class information. It covers fundamental concepts such as resistors in series and parallel, voltage and current division, and measurement techniques. Additionally, it discusses the differences between ideal and realistic voltage and current sources, as well as methods of taking electrical measurements.