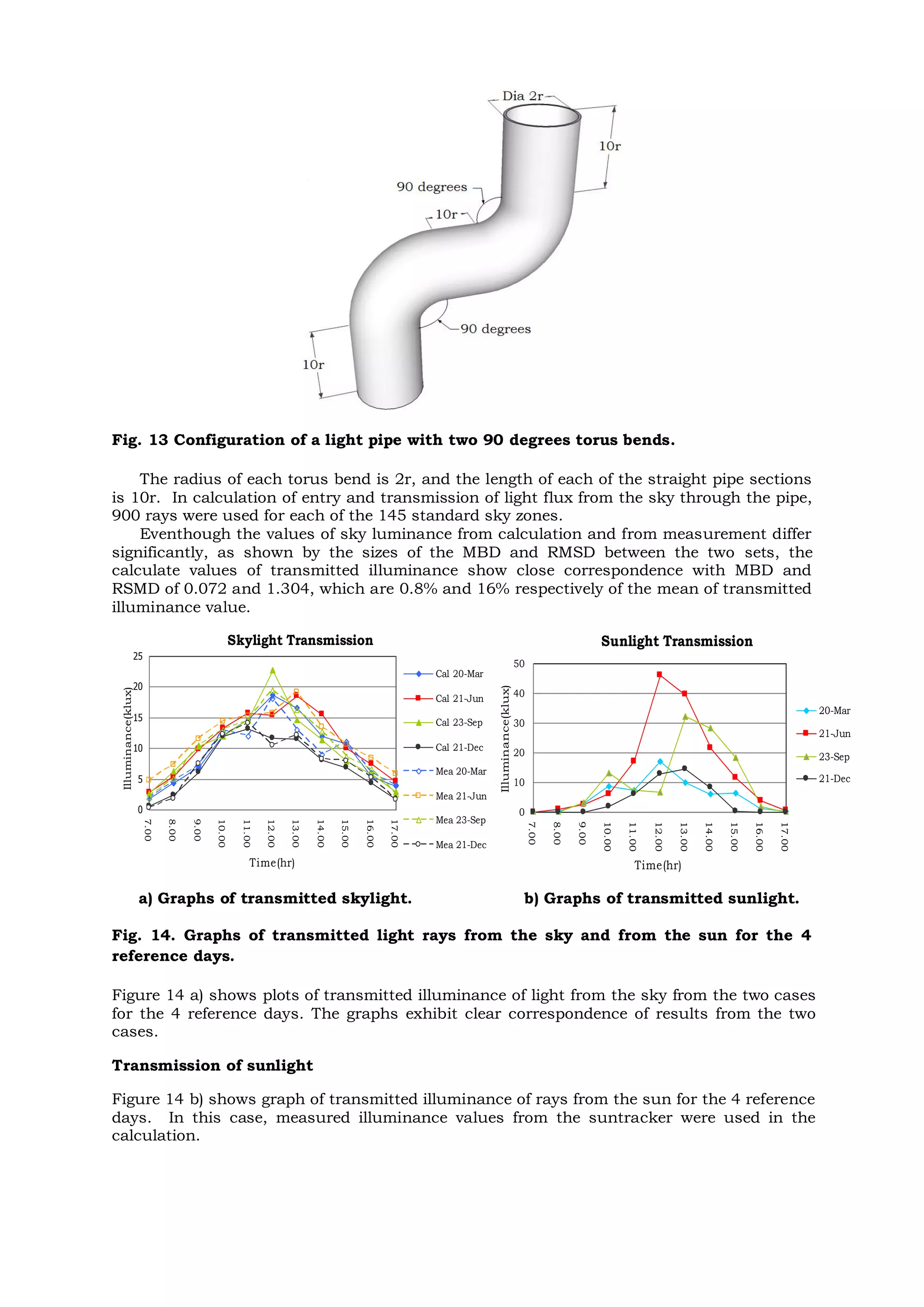

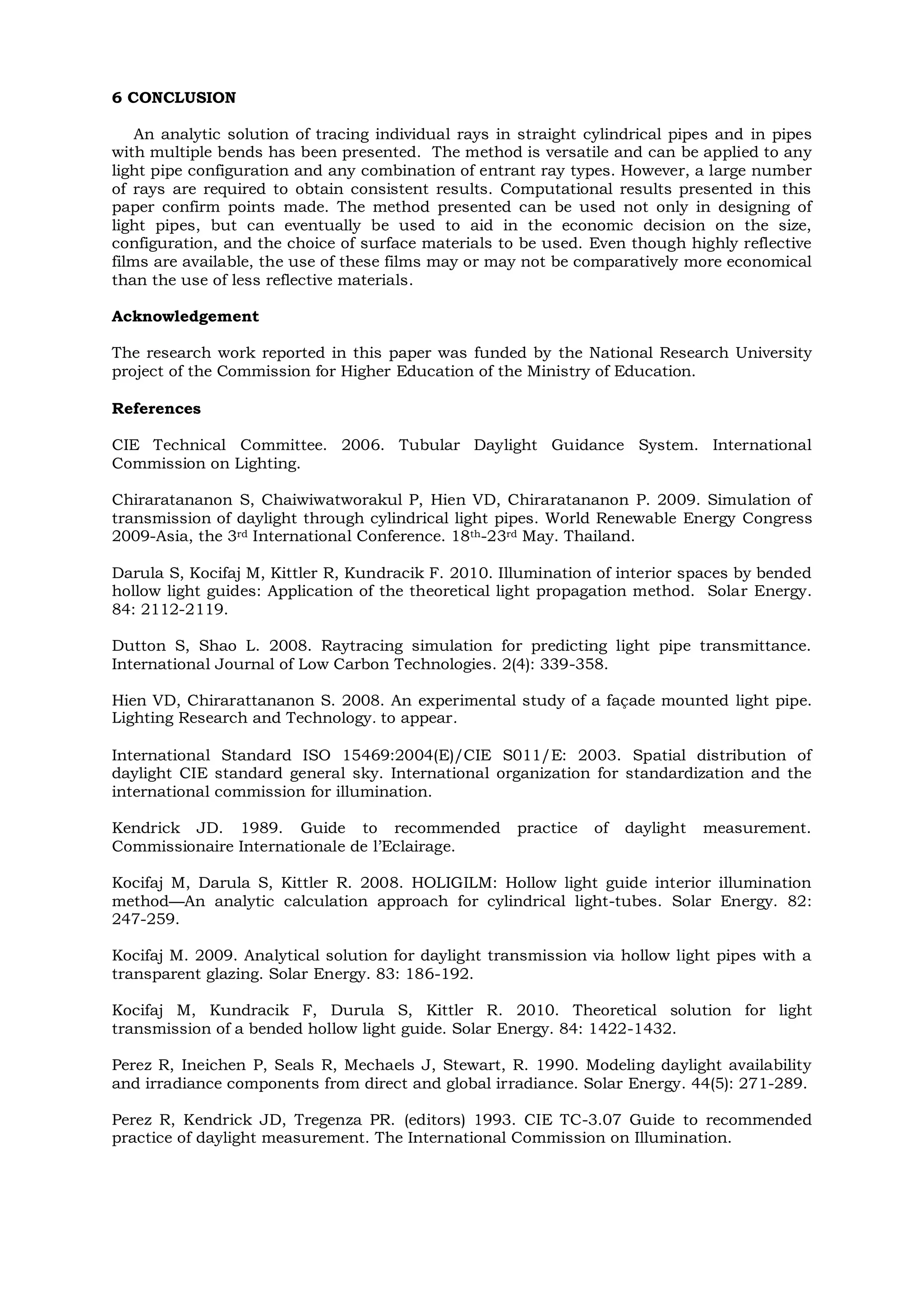

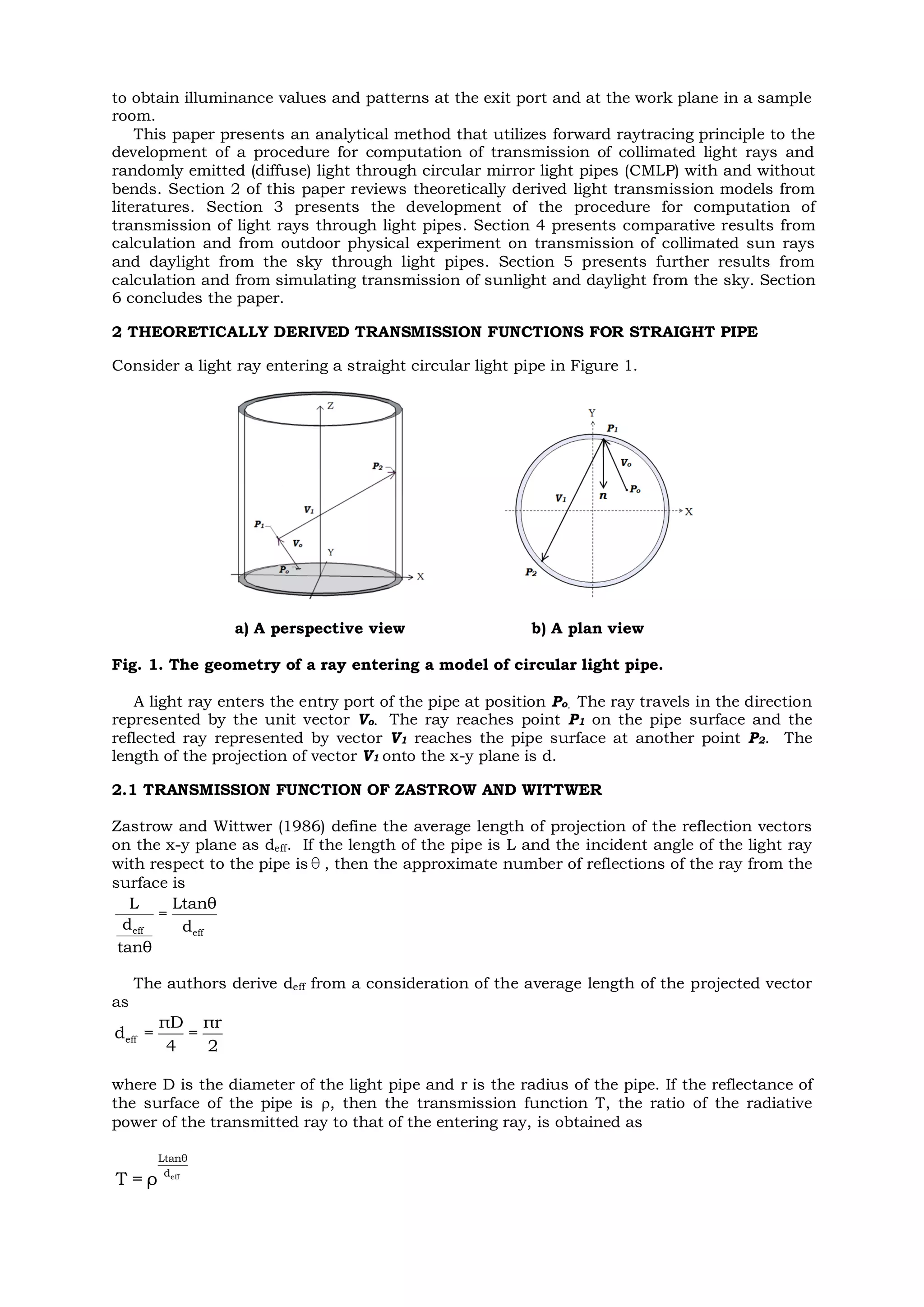

This document presents the results of a study on modeling and simulating the transmission of daylight through circular light pipes with and without bends. It describes an analytical raytracing method developed to compute the transmission of collimated and diffuse light through such pipes. Experimental results on light transmission through straight pipes and pipes with bends are shown to match well with calculations. The paper also compares transmitted daylight illuminance values using measured versus generated sky luminance data as light inputs.

![This relationship was shown by (Swift and Smith 1995) to be only valid for pipes with

high aspect ratios (larger value of the ratio of pipe length to pipe diameter), small incident

angles, and high surface reflectance.

2.2 TRANSMISSION FUNCTION OF SWIFT AND SMITH

Swift and Smith (1995) consider the transmission function of (Zastrow and Wittwer 1986) to

be an approximation and develop an exact analytical expression to be used instead. The

expression is:

1 ptanθ2

int[ ]

s

2

s=0

4 s ptanθ

T = ρ (1-(1- ρ)(-int[ ]))ds

π s1- s

where

L

p =

D

, is the aspect ratio or the length to diameter ratio, and where int[x] denotes

the integer part of x. This function T represents the average transmission for light rays that

are collimated in one direction.

3 RAYTRACING FOR STRIGHT PIPES AND PIPES WITH BENDS

The raytracing method is based on tracing of specular reflection of individual rays.

3.1 APPLICATION OF RAYTRACING TO RECTANGULAR PIPES

Raytracing has been applied successfully to the study of façade-mounted rectangular pipes

by (Hien and Chirarattananon 2008). (Dutton and Shao 2008), use long thin rectangular

sections to form approximate circular shaped pipes and simulate light pipe transmission by

the use of Photopia, a computer program. When the authors simulate the transmission of

collimated rays, the results from Photopia calculation match very well with those calculated

from the transmission function of (Swift and Smith 1995).

3.2 BACKWARD RAYTRACING METHOD FOR CIRCULAR LIGHT PIPES

Kocifaj etal (2008) develop a method called HOLIGILM for calculation of illuminance on an

incremental area at the exit port of a circular light pipe by considering backward tracing of

a light ray through the entry dome or port to a sky zone. For the same incremental area,

rays from all directions are traced until light fluxes from all zones of the sky and light flux

from the sun (if present) are accounted. Light fluxes from the sky zones and sun contribute

to the illuminance of the incremental area. Light flux passing the incremental area at the

exit port constitutes exitance from the area and is then used to calculate luminance,

intensity, and eventually the illuminance on an area on the work plane in a given room.

Kocifaj (2009) illustrates numerical results from the method and notes that for relatively

long pipes, ‘distorted image of the sun is spread over a circular region in the work plane’.

The author also reports the use of the method for calculation of transmission of beam

sunlight and daylight under clear and cloudy sky using two standard CIE sky luminance

distributions, (CIE 2003). Both transparent and diffuse optical components are used

alternately at the exit port.

Kocifaj etal (2010) extends the HOLIGILM method to the case where two straight circular

pipes are connected at an angle at a flat interface, where the shape of the interface becomes

elliptical. Darula etal (2010) illustrates results from the use of the extended method. Here,

the authors also note the existence of a circular region on the work plane due to

transmission of light from the sun. The authors also note that their method is fast, but the

speed and precision of calculation depends on the fineness of a ‘grid’ used.

The reports of (Darula etal 2010) and of (Kocifaj 2009) show that there is a circular band

on the work plane in the sample room from transmission of beam sunlight through a pipe,

be it a single straight pipe or two straight pipes connected to form a single pipe.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a6a263eb-3a4b-483e-87dc-ed01194f8133-150725163242-lva1-app6891/75/LEUKOS_International_Journal-4-2048.jpg)

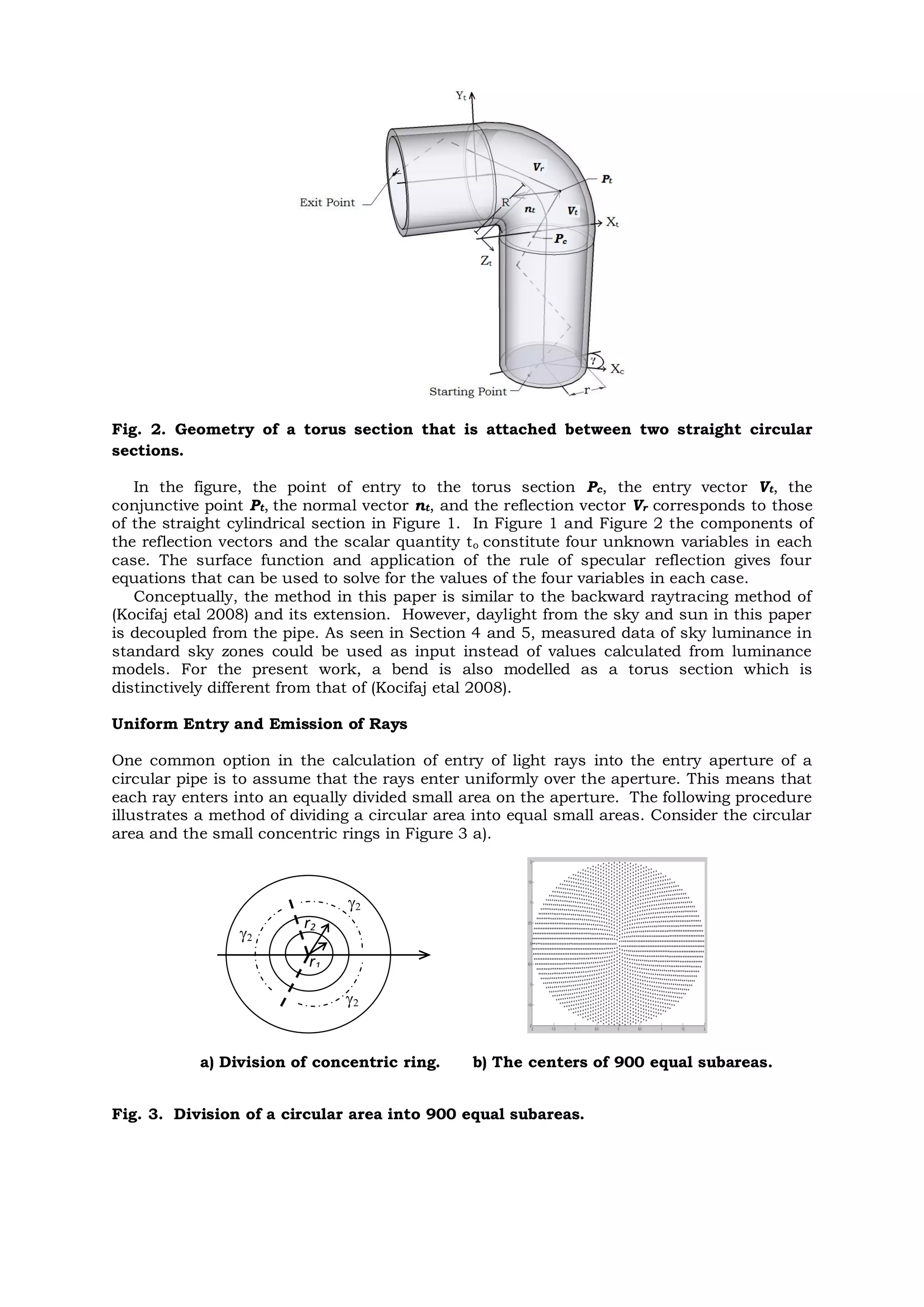

![The innermost ring has a radius of r1. The area of this circle is

2

2πr

1

. The next circle has a

radius 2 1r = 2r . The subsequent circles have radii of 3 1 n 1r = 3r ,…,r = nr . This means that the

successive rings have the following areas,

2 2 2

2 1 1

2 2 2 2

n 1 1

r : 2πr [2 -1] = 3(2πr ),

r : 2πr [(n) - (n -1) ] = (2n -1)(2πr ).

To obtain equal small incremental areas, the area of the ring between the circles of

radius r1 and r2 is divided into 3 equal areas. The angle 2γ in Figure 3 then equals

2π

3

. For

the ring between the circles of radii ri-1 and ri, the size of the corresponding angle iγ

equals

2π

2i -1

. The number of the small equal areas sums to n2. Figure 3 b) illustrates the

points of entry of each ray into the entry port of a pipe.

Random Rays

The elevation angle and the azimuth angle of a unit vector that represents a ray

randomly emitted from a diffuse surface are obtained from, (Tregenza 1993),

, and

,

sinθ = R

1

= 2πR

2

where R1 and R2 are random numbers each with a value between 0 and 1.

4 COMPUTATIONAL AND EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

We first examine results from computation and from physical experiment of light

transmission through straight pipes and pipes with bends. In the computation to be

described, the rays are emitted uniformly into the entry aperture of circular light pipes in

accordance with the method of Section 3.3. This is in contrast to that in (Chiraratananon

etal 2009) that uses randomly distributed rays. The authors are convinced that for limited

number of rays, the method used here produces more consistent results.

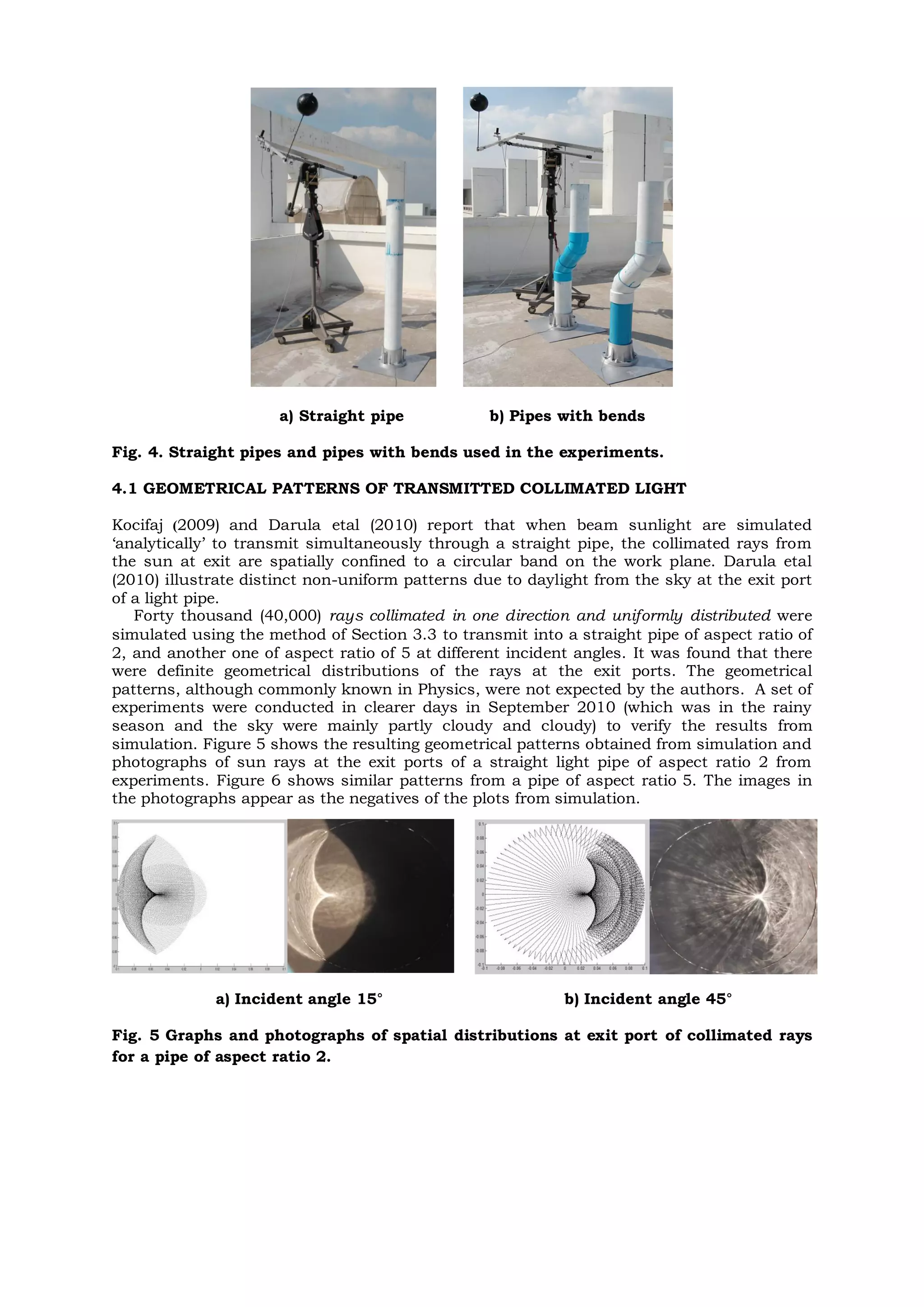

A set of light pipes were fabricated from polyvinyl chloride (pvc) pipes commonly used in

domestic plumbing. The diameters of the pipes are 150 mm. Bend sections from pvc pipes

are used as torus bends for the light pipes. The inner surfaces of all pipe sections were

lined manually with Daylighting Film of 3M Inc., USA. The film has a reflectance greater

than 0.99 as given in the specification. The surfaces of the finished pipes, especially the

bend sections, are not expected to be as reflective as that of the original film. Figure 4

shows photographs of the straight pipes and pipes with two 450 bends.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a6a263eb-3a4b-483e-87dc-ed01194f8133-150725163242-lva1-app6891/75/LEUKOS_International_Journal-7-2048.jpg)