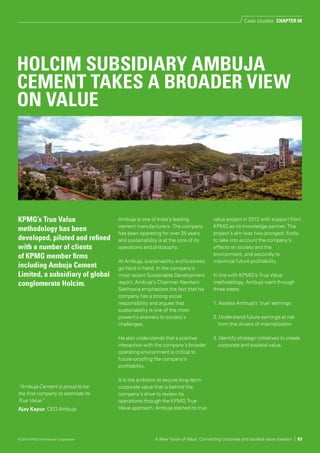

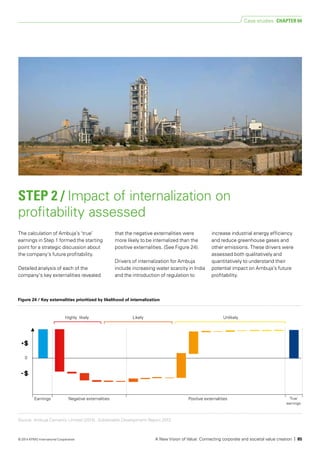

The age of internalization is here as externalities are increasingly impacting corporate value. Growing globalization, connectivity, and environmental challenges are transforming the operating landscape for businesses. Regulations, stakeholder pressure, and market dynamics are driving the internalization of externalities, meaning companies are more accountable for societal costs and can capture more value from societal benefits. As externalities influence revenues, costs, and risks, business leaders must understand and address externalities to protect and create long-term corporate and societal value.