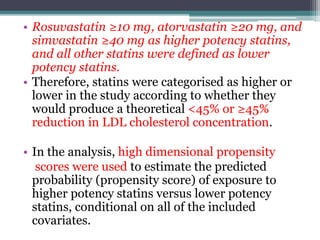

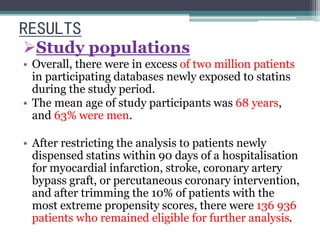

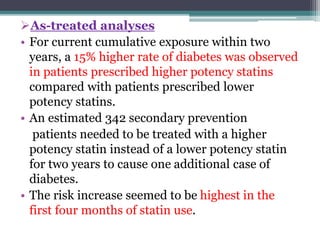

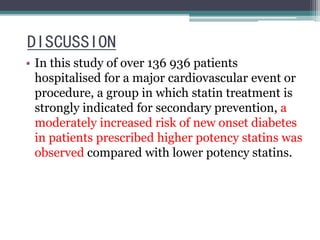

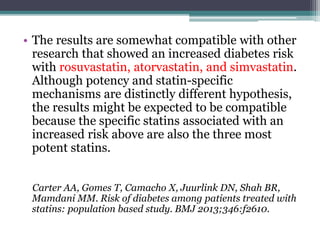

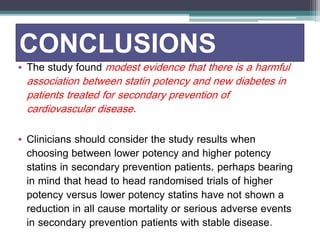

This document summarizes a study that examined the risk of new diabetes with higher potency statins compared to lower potency statins. It discusses two previous meta-analyses that found a small increased risk of diabetes with statin use. The study analyzed administrative databases covering millions of patients and found a 15% higher rate of new diabetes over 2 years in those prescribed higher potency statins for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events compared to lower potency statins. Higher potency statins were associated with one additional case of diabetes for every 342 patients treated over 2 years. The increased risk was highest in the first 4 months of statin use.

![28th february 2012

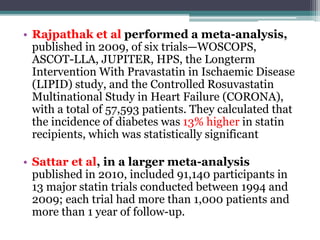

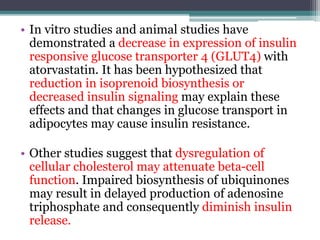

A meta-analysis by Rajpathak et al.,20 which included 6 statin trials with

57,593 FDA’s participants, review of the also results reported from the a small Justification increase for in diabetes the Use of

risk

(Statins relative in risk Primary [RR] 1.13; Prevention: 95% CI 1.03-an Intervention 1.23), with no Trial evidence Evaluating

of

heterogeneity Rosuvastatin across (JUPITER) trials. reported A recent a study 27% increase by Culver in et investigator-reported

al.,26 using data

from the Women’s diabetes mellitus Health Initiative, in rosuvastatin-reported treated that statin patients

use conveys an

increased risk of new-onset diabetes in postmenopausal women, and

noted that the effect appears to be a medication class effect, unrelated to

potency or to individual statin.

Based on clinical trial meta-analyses and epidemiological data from the

published literature, information concerning an effect of statins on

incident diabetes and increases in HbA1c and/or fasting plasma glucose

was added to statin labels.

compared to placebo-treated patients. High-dose atorvastatin had

also been associated with worsening glycemic control in the

Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy –

Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 22 (PROVE-IT TIMI 22)

substudy. FDA also reviewed the published medical literature. A

meta-analysis by Sattar et al.,19 which included 13 statin trials with

91,140 participants, reported that statin therapy was associated with

a 9% increased risk for incident diabetes (odds ratio [OR] 1.09; 95%

confidence interval [CI] 1.02-1.17), with little heterogeneity

(I2=11%) between trials.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jc2-141203151012-conversion-gate02/85/Jc2-24-320.jpg)

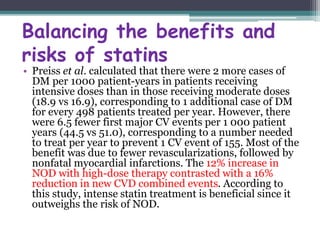

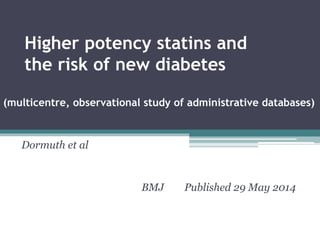

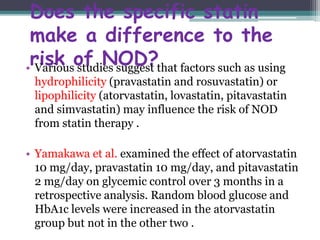

![New diabetes occurred in 2,226 (4.89%) of the

statin recipients and in 2,052 (4.5%) of the

placebo recipients, an absolute difference of

0.39%, or 9% more (odds ratio [OR] 1.09; 95%

confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.17). The

incidence of diabetes varied substantially among

the 13 trials, with only JUPITER and PROSPER

finding statistically significant increases in rates

(26% and 32%, respectively).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jc2-141203151012-conversion-gate02/85/Jc2-26-320.jpg)

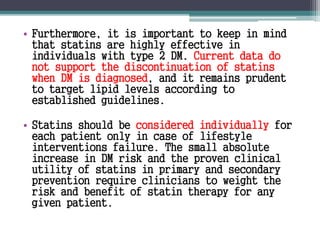

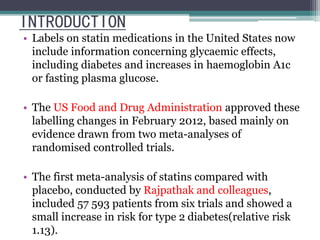

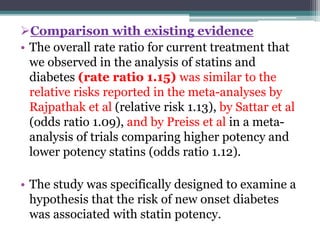

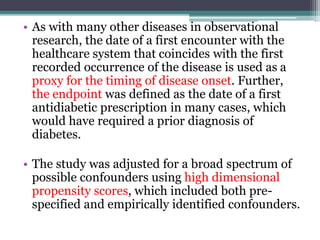

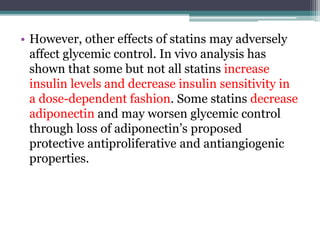

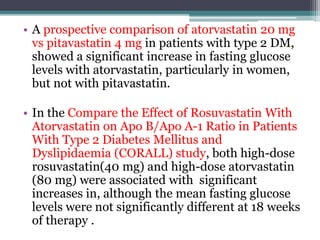

![• A meta-analysis by Sattar et al. did not find a clear

difference between lipophilic statins (OR 1.10 vs

placebo) and hydrophilic statins (OR 1.08). In

analysis by statin type, the combined rosuvastatin

trials were significant in favor of a higher DM risk

(odds ratio[OR]: 1.18; 95%CI; 1.04-1.44).

Insignificant trends were noted for atorvastatin trials

(OR: 1.14) and simvastatin trials (OR: 1.11) and less

so for pravastatin (OR: 1.03); the OR for lovastatin

was 0.98.

• This may suggest that there is a stronger effect with

more potent statins or with greater lowering of LDL-C.

Furthermore, this evidence does not support a

protective or neutral role for statin hydrophilicity in

the pathogenesis of NOD.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jc2-141203151012-conversion-gate02/85/Jc2-32-320.jpg)