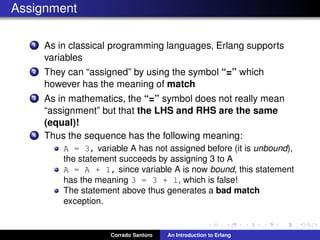

Erlang uses pattern matching rather than variable assignment. When using the = symbol in Erlang, it matches the left-hand side to the right-hand side rather than assigning a value. This means a variable can only be matched once - a bound variable cannot be reused like in other languages. So a statement like A = A + 1 would generate an error, as it is trying to match the already bound variable A to a new value.

![Lists

An Erlang list is an ordered set of any Erlang term.

It is syntactical expressed as a comma-separated set of

elements, delimited with “[” and “]”.

Example: [7, 9, 15, 44].

“Roughly speaking”, a list is a C array.

However it’s not possible to directly get the i-th element, but we

can separate the first element from the tail of the list.

Using only this operation, the complete manipulation of a list is

possible!

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-14-320.jpg)

![Lists: separation operator

[ First | Rest ] = List.

First will contain the first element of the list.

Rest will contain the sublist of the element starting from the

second till the end.

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-15-320.jpg)

![Lists: Examples

[ First | Rest ] = [7, 9, 15, 44].

First = 7

Rest = [9, 15, 44]

[ Head | Tail ] = [16].

Head = 16

Tail = []

[ First | Tail ] = [].

runtime error! It is not possible to get the first element

from an empty list.

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-16-320.jpg)

![Example: sum of all elements of a list

Mathematical formulation

sum([x1, . . . , xn]) =

n

i=1

xi

C Implementation:

✞

int sum (int * x, int n) {

int i, res = 0;

for (i = 0;i < n;i++)

res += x[i];

return res;

}

✡✝ ✆

Erlang does not have the construct to get the i-th element, nor

the for. We must use recursion!

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-17-320.jpg)

![Example: sum of all elements of a list

Mathematical formulation with recursion

sum([]) = 0

sum([x1, x2, . . . , xn]) = x1 + sum([x2, . . . , xn])

Let’s do it in Erlang:

✞

sum([]) -> 0;

sum([ Head | Tail ]) -> Head + sum(Tail).

%% sum(L) -> [ Head | Tail ] = L, Head + sum(Tail).

✡✝ ✆

C solution uses 6 lines of code and 2 local variables.

Erlang solution uses only 2 lines of code!

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-18-320.jpg)

![List Construction

Operator “|” is also used to build a list.

List = [ FirstElement | TailOfTheList ].

It builds a list by chaining the element FirstElement at with

the list TailOfTheList.

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-19-320.jpg)

![List Construction: Examples

X = [7 | Y].

Y = [9, 15, 44]

X = [7, 9, 15, 44]

X = [Y | Z].

X = 16 e Z = []

X = [16]

X = [Y | [1, 2, 3]].

X = 16

X = [16, 1, 2, 3]

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-20-320.jpg)

![Example: double each element of a list

C solution:✞

void doubling (int * x, int n) {

int i;

for (i = 0;i < n;i++) x[i] *= 2;

}

✡✝ ✆

Erlang solution:

✞

doubling([]) -> [];

doubling([ Head | Tail ]) -> [Head * 2 | doubling (Tail)].

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-21-320.jpg)

![Example: filtering a list

Let’s write a function that, given a list L, returns a new list

containing only the elements of L greater than 10.

Solution 1:✞

filter([]) -> [];

filter([ Head | Tail ]) when Head > 10 ->

[Head | filter (Tail)];

filter([ Head | Tail ]) -> filter (Tail).

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-22-320.jpg)

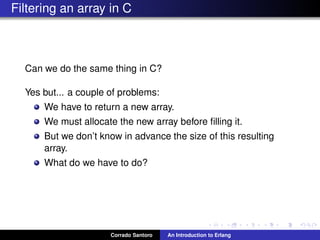

![Array filtering in C

✞

int * filter (int * x, int n, int * newN) {

int i, j, newSize = 0;

int * result;

/* first, let’s compute the size of the resulting array */

for (i = 0;i < n;i++)

if (x[i] > 10) newSize ++;

/* then let’s allocate the resulting array */

result = malloc (newSize * sizeof (int));

/* finally let’s fill the array */

for (i = 0, j = 0; i < n;i++) {

if (x[i] > 10) {

result[j] = x[i];

j++;

}

}

*newN = newSize;

return result;

}

✡✝ ✆

“Some more lines” w.r.t. Erlang solution.

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-24-320.jpg)

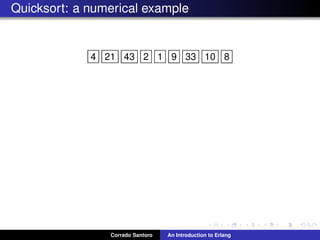

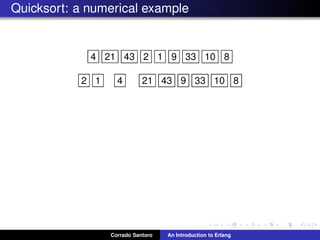

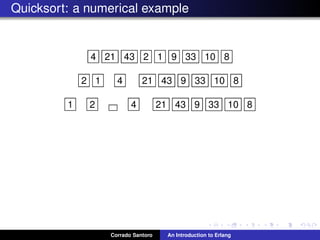

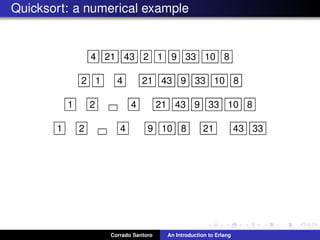

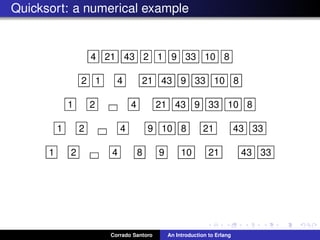

![Quicksort: implementation

Mathematical formulation

quicksort([ ]) = [ ]

quicksort([x1, x2, . . . , xn]) = quicksort([xi : xi ∈ [x2, . . . , xn], xi < x1]) ⊕

⊕ [x1] ⊕

⊕ quicksort([xi : xi ∈ [x2, . . . , xn], xi >= x1])

4 21 43 2 1 9 33 10 8

2 1 4 21 43 9 33 10 8

1 2 4 21 43 9 33 10 8

1 2 4 9 10 8 21 43 33

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-32-320.jpg)

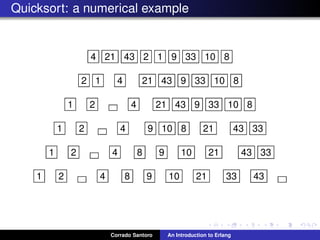

![Quicksort: implementation

Mathematical formulation

quicksort([ ]) = [ ]

quicksort([x1, x2, . . . , xn]) = quicksort([xi : xi ∈ [x2, . . . , xn], xi < x1]) ⊕

⊕ [x1] ⊕

⊕ quicksort([xi : xi ∈ [x2, . . . , xn], xi >= x1])

✞

quicksort([]) -> [];

quicksort([X1 | L]) ->

quicksort([X || X <- L, X < X1]) ++ [X1] ++

quicksort([X || X <- L, X >= X1]).

✡✝ ✆

Here we used the Erlang operator “++” to concatenate two lists.

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-33-320.jpg)

![Assignment

A bound variable cannot be thus reused as in classical

imperative language

This seems weird but has some precise reasons:

1 The symbol “=” has its own mathematical meaning: equal!

2 This semantics makes pattern matching very easy

Example: Ensuring that the first two elements of a list are the

same:

✞

[H, H | T ] = MyList

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-36-320.jpg)

![The “list member” function

Matching is very useful in function clause heads

Let’s implement a function which checks if an element

belongs to the list

✞

member(X, []) -> false;

member(X, [X | T]) -> true;

member(X, [H | T]) -> member(X, T).

✡✝ ✆

The code above may be rewritten in a more elegant way by

using the “ ” symbol which means “don’t care”

✞

member(_, []) -> false;

member(X, [X | _]) -> true;

member(X, [_ | T]) -> member(X, T).

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-37-320.jpg)

![A step behind: overview of Erlang data types

Integers, the are “big-int”, i.e. integers with no limit

Reals, usually represented in floating-point

atoms, Symbolic constants made of literals starting with

lowercase. Example: hello, ciao, thisIsAnAtom.

They are atomic entities; even if they are literals, they

cannot be treated as “classical” C or Java strings. Instead,

they play the role of symbolic constants (like C #define

or Java final).

tuples, ordered sequences of elements representing, in

general, a structured data.

Examples: {item, 10}, {15, 20.3, 33},

{x, y, 33, [1, 2, 3]}.

The number of elements is fixed at creation time and

cannot be changed. They are something like C structs.

lists

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-38-320.jpg)

![Summing list elements with tail recursion

Not tail recursive:

✞

sum([]) -> 0;

sum([ Head | Tail ]) -> Head + sum(Tail).

✡✝ ✆

Tail recursive:

✞

sum(L) -> sum(L, 0).

sum([], Acc) -> Acc;

sum([ Head | Tail ], Acc) -> sum(Tail, Head + Acc).

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-41-320.jpg)

![Dictionaries

Let us implement a module which handles a dictionary with data in

the form:

[{key1, value1}, {key2, value2}, ... ]

Exports:

new()→[]

insert(Dict, Key, Value)→NewDict

delete(Dict, Key)→NewDict

member(Dict, Key)→bool

find(Dict, Key)→{ok, Value} | error

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-43-320.jpg)

![Dictionary

✞

-module(dictionary).

-export([new/0, insert/3, delete/2, member/2, find/2]).

new() -> [].

member([], _Key) -> false;

member([{Key, _Value} | _Tail], Key) -> true;

member([ _ | Tail], Key) -> member(Tail, Key).

insert(Dict, Key, Value) ->

M = member(Dict, Key),

if

M -> % The key exists

Dict;

true -> % The key does not exist

[{Key, Value} | Dict]

end.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-44-320.jpg)

![Dictionary

✞

-module(dictionary).

-export([new/0, insert/3, delete/2, member/2, find/2]).

new() -> [].

member([], _Key) -> false;

member([{Key, _Value} | _Tail], Key) -> true;

member([ _ | Tail], Key) -> member(Tail, Key).

insert(Dict, Key, Value) ->

case member(Dict, Key) of

true -> % The key exists

Dict;

false -> % The key does not exist

[{Key, Value} | Dict]

end.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-47-320.jpg)

![Dictionary (Part II)

✞

-module(dictionary).

-export([new/0, insert/3, delete/2, member/2, find/2]).

...

delete([], _Key) -> [];

delete([{Key, _Value} | Tail], Key) -> delete(Tail, Key);

delete([ Head | Tail], Key) -> [Head | delete(Tail, Key) ].

find([], _Key) -> error;

find([{Key, Value} | _Tail], Key) -> {ok, Value};

find([ _ | Tail], Key) -> find(Tail, Key).

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-48-320.jpg)

![Strings

An Erlang string is a list in which each element is the ASCII code of

the n-th character:

The string Hello can be expressed in erlang as:

"Hello"

[72,101,108,108,111]

[$H,$e,$l,$l,$o]

The literal $car is a short-cut for “ASCII code of character car”.

A string can be manipulated as a list:

[Head | Tail] = "Hello"

Head = 72

Tail = "ello"

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-49-320.jpg)

![Exercise on strings and lists

Write a function:

split(String, SepChar) → [Token1, Token2, ...]

which separates a string into tokens (returns a list of string) on the

basis of the separation char SepChar.

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-50-320.jpg)

![Exercise on Strings and Lists

✞

-module(exercise).

-export([split/2, reverse/1]).

split(String, Sep) -> split(String, Sep, [], []).

split([], _Sep, [], ListAccumulator) ->

reverse(ListAccumulator);

split([], Sep, TokenAccumulator, ListAccumulator) ->

split([], Sep, [], [reverse(TokenAccumulator) | ListAccumulator]);

split([Sep | T], Sep, [], ListAccumulator) ->

split(T, Sep, [], ListAccumulator);

split([Sep | T], Sep, TokenAccumulator, ListAccumulator) ->

split(T, Sep, [], [reverse(TokenAccumulator) | ListAccumulator]);

split([H | T], Sep, TokenAccumulator, ListAccumulator) ->

split(T, Sep, [H | TokenAccumulator], ListAccumulator).

reverse(List) -> reverse(List, []).

reverse([], Acc) -> Acc;

reverse([H | T], Acc) -> reverse(T, [H | Acc]).

✡✝ ✆Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-51-320.jpg)

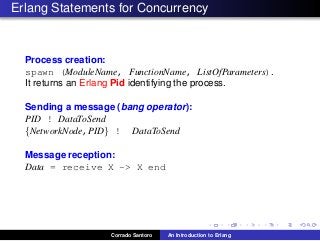

![A very simple concurrent program

Let’s write a function that spawns a process, sends a data and

gets back a reply.

✞

-module(ping_pong).

-export([caller/0, responder/0]).

caller() ->

Pid = spawn(ping_pong, responder, []),

Pid ! {self(), 100},

receive

Reply -> ok

end.

responder() ->

receive

{From, Data} ->

From ! Data + 1

end.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-56-320.jpg)

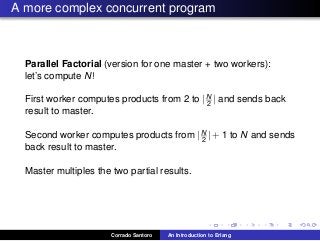

![Parallel Factorial with two workers

✞

-module(fact_parallel).

-export([fact_parallel/1, fact_worker/3]).

fact_part(To, To) -> To;

fact_part(X, To) -> X * fact_part(X + 1, To).

fact_worker(Master, From, To) ->

PartialResult = fact_part(From, To),

Master ! PartialResult.

fact_parallel(N) ->

Middle = trunc(N / 2),

ProcOneArguments = [self(), 2, Middle],

ProcTwoArguments = [self(), Middle + 1, N],

spawn(fact_parallel, fact_worker, ProcOneArguments),

spawn(fact_parallel, fact_worker, ProcTwoArguments),

receive Result1 -> ok end,

receive Result2 -> ok end,

Result1 * Result2.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-58-320.jpg)

![Exercise: Parallel Factorial with “m” workers

Let’s compute N!

The interval [2, N] is subdivided into “m” subintervals.

Each worker computes the sub-product of its sub-interval and

sends back result to master.

Master multiples all the partial results.

1 Compute each subinterval [Ai, Bi ];

2 Spawn the m processes and gather the PIDs into a list;

3 Scan the list and wait, for each PID, the result; gather the

result into a list;

4 Multiply all the results together and return the final number.

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-59-320.jpg)

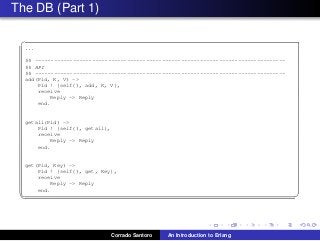

![The DB (Part 1)

✞

-module(db).

-export([start/0, db_loop/1, add/3, getall/1, get/2]).

start() ->

spawn(db, db_loop, [ [] ]).

db_loop(TheDB) ->

receive

{From, add, Key, Value} ->

case lists:keymember(Key, 1, TheDB) of

true -> % the key exists returns an error

From ! duplicate_key,

db_loop(TheDB);

false -> % the key does not exist, add it

From ! ok,

db_loop( [ {Key, Value} | TheDB ])

end;

{From, getall} ->

From ! TheDB,

db_loop(TheDB);

{From, get, Key} ->

case lists:keyfind(Key, 1, TheDB) of

false -> % key not found

From ! not_found;

{K, V} ->

From ! {K, V}

end,

db_loop(TheDB)

end.

...

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-61-320.jpg)

![Distributed Ping-pong

Let’s write a ping-pong program working in distributed Erlang.

✞

-module(d_ping_pong).

-export([start_responder/0, responder/0, ping/2, stop/1]).

start_responder() ->

Pid = spawn(d_ping_pong, responder, []),

register(responder, Pid).

responder() ->

receive

{From, Data} ->

From ! Data + 1,

responder();

bye ->

ok

end.

ping(Node, Data) ->

{responder, Node} ! {self(), Data},

receive

Reply -> Reply

end.

stop(Node) ->

{responder, Node} ! bye.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-65-320.jpg)

![Testing the example

✞

$ erl -name pluto@127.0.0.1 -setcookie mycookie

Erlang R16B03 (erts-5.10.4) [source] [smp:4:4] [async-threads:10] [kernel-poll:false]

Eshell V5.10.4 (abort with ˆG)

(pluto@127.0.0.1)1> net_adm:ping(’pippo@127.0.0.1’).

pong

(pluto@127.0.0.1)2> d_ping_pong:start_responder().

true

✡✝ ✆

✞

$ erl -name pippo@127.0.0.1 -setcookie mycookie

Erlang R16B03 (erts-5.10.4) [source] [smp:4:4] [async-threads:10] [kernel-poll:false]

Eshell V5.10.4 (abort with ˆG)

(pippo@127.0.0.1)1> d_ping_pong:ping(’pluto@127.0.0.1’, 10).

11

(pippo@127.0.0.1)2> d_ping_pong:ping(’pluto@127.0.0.1’, 44).

45

(pippo@127.0.0.1)3> d_ping_pong:stop(’pluto@127.0.0.1’).

bye

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-66-320.jpg)

![Linked Processes: an Example

✞

-module(test_link).

-export([start/0, one/0, two/0, stop/0]).

start() ->

Pid = spawn(test_link, one, []),

register(one, Pid).

one() ->

Pid = spawn_link(test_link, two, []),

register(two, Pid),

one_loop().

one_loop() ->

io:format("Onen"),

receive

bye ->

ok % exit(normal) or exit(error)

after 1000 ->

one_loop()

end.

...

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-72-320.jpg)

![Linked Processes: an Example (2)

✞

...

two() ->

%process_flag(trap_exit,true),

two_loop().

two_loop() ->

io:format("Twon"),

receive

Msg ->

io:format("Received ˜pn", [Msg])

after 1000 ->

two_loop()

end.

stop() ->

one ! bye.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-73-320.jpg)

![Supervisor (Part 1)

✞

%%

%% sup.erl

%%

-module(sup).

-export([start/0, sup_starter/0, add/3, get_proc_list/0]).

start() ->

Pid = spawn(sup, sup_starter, []),

register(sup, Pid).

sup_starter() ->

process_flag(trap_exit, true),

sup_loop([]).

...

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-75-320.jpg)

![Supervisor (Part 2)

✞

...

sup_starter() ->

process_flag(trap_exit, true),

sup_loop([]).

sup_loop(ListOfProcesses) ->

receive

{From, proc_list} ->

From ! ListOfProcesses,

sup_loop(ListOfProcesses);

{From, add_proc, Module, Function, Arguments} ->

Pid = spawn_link(Module, Function, Arguments),

sup_loop( [ {Pid, Module, Function, Arguments} | ListOfProcesses]);

{’EXIT’, Pid, Reason} ->

io:format("PID ˜p Terminated with ˜pn", [Pid, Reason]),

case find_process(Pid, ListOfProcesses) of

{ok, M, F, A} ->

io:format("Restarting ˜p:˜pn", [M, F]),

NewPid = spawn_link(M, F, A),

sup_loop(pid_replace(Pid, NewPid, ListOfProcesses));

error ->

io:format("PID not found in list!n"),

sup_loop(ListOfProcesses)

end

end.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-76-320.jpg)

![Supervisor (Part 3)

✞

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% API

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

add(M, F, A) ->

sup ! {self(), add_proc, M, F, A},

ok.

get_proc_list() ->

sup ! {self(), proc_list},

receive

ProcList -> ProcList

end.

%% --------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% Internal functions

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

find_process(_Pid, []) -> error;

find_process(Pid, [{Pid, M, F, A} | _Tail]) -> {ok, M, F, A};

find_process(Pid, [{_OtherPid, _M, _F, _A} | Tail]) -> find_process(Pid, Tail).

pid_replace(_Pid, _NewPid, []) -> [];

pid_replace(Pid, NewPid, [{Pid, M, F, A} | Tail]) -> [ {NewPid, M, F, A} | Tail];

pid_replace(Pid, NewPid, [{OtherPid, M, F, A} | Tail]) ->

[ {OtherPid, M, F, A} | pid_replace(Pid, NewPid, Tail) ].

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-77-320.jpg)

![Supervisor (Part 4)

✞

-module(p).

-export([p1/0, p2/1]).

p1() ->

io:format("One!n"),

timer:sleep(1000),

p1().

p2(X) when X > 10 ->

B = 0, X / B;

%% provoke a ’badartih’ error

p2(X) ->

io:format("Two: ˜pn", [X]),

timer:sleep(1000),

p2(X+1).

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-78-320.jpg)

![Supervisor (Part 5)

✞

corrado@Corrado-1215P:˜/didattica/MasterCloud/erlang/software$ erl

Erlang R16B03 (erts-5.10.4) [source] [smp:4:4] [async-threads:10] [kernel-poll:false]

Eshell V5.10.4 (abort with ˆG)

1> sup:start().

true

2> sup:add(p, p1, []).

ok

One!

3> sup:add(p, p2, [ 5 ]).

Two: 5

ok

One!

Two: 6

One!

Two: 7

One!

Two: 8

One!

Two: 9

One!

Two: 10

One!

PID <0.39.0> Terminated with {badarith,[{p,p2,1,[{file,"p.erl"},{line,11}]}]}

Restarting p:p2

Two: 5

4>

=ERROR REPORT==== 24-Mar-2015::10:39:55 ===

Error in process <0.39.0> with exit value: {badarith,[{p,p2,1,[{file,"p.erl"},{line,11}]}]}

One!

Two: 6

One!

Two: 7 Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-79-320.jpg)

![The Database Example with gen server

✞

-module(database).

%% this module implements a gen_server behaviour

-behaviour(gen_server).

-export([start/0, init/1, .... ]).

start() ->

%% Module is ’database’ (the same),

%% No arguments

%% No options

gen_server:start_link(database, [], []).

init(Args) ->

{ok, []}. %% start with an empty database

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-88-320.jpg)

![The Database Example with gen server

✞

-module(database).

-behaviour(gen_server).

-export([start/0, add/3, getall/1, get/2, init/1, handle_call/3]).

start() ->

gen_server:start_link(database, [], []).

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% API

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

add(Pid, K, V) -> gen_server:call(Pid, {add, K, V}).

getall(Pid) -> gen_server:call(Pid, {getall}).

get(Pid, Key) -> gen_server:call(Pid, {get, Key}).

...

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-91-320.jpg)

![The Database Example with gen server

✞

...

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% CALLBACKS

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

init(Args) -> {ok, []}. %% start with an empty database

handle_call({add, Key, Value}, _From, TheDB) ->

case lists:keymember(Key, 1, TheDB) of

true -> % the key exists returns an error

{reply, duplicate_key, TheDB};

false -> % the key does not exist, add it

{reply, ok, [ {Key, Value} | TheDB ]}

end;

handle_call({getall}, _From, TheDB) -> {reply, TheDB, TheDB};

handle_call({get, Key},_From, TheDB) ->

case lists:keyfind(Key, 1, TheDB) of

false -> % key not found

{reply, not_found, TheDB};

{K, V} ->

{reply, {K, V}, TheDB}

end.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-92-320.jpg)

![A “Registered” Database (with “stop” API)

✞

-module(reg_database).

-behaviour(gen_server).

-export([start/0, add/2, getall/0, get/1, stop/0, init/1, handle_call/3, terminate/2]).

-define(SERVER_NAME, mydb).

start() ->

gen_server:start_link({local, ?SERVER_NAME}, ?MODULE, [], []).

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% API

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

add(K, V) -> gen_server:call(?SERVER_NAME, {add, K, V}).

getall() -> gen_server:call(?SERVER_NAME, {getall}).

get(Key) -> gen_server:call(?SERVER_NAME, {get, Key}).

stop() -> gen_server:call(?SERVER_NAME, {stop}).

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% CALLBACKS

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

...

handle_call({stop}, _From, TheDB) -> {stop, normal, ok, TheDB};

...

terminate(Reason,State) -> io:format("DB is terminatingn").

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-93-320.jpg)

![The gen fsm of the fixed-line phone

✞

-module(phone).

-behaviour(gen_fsm).

-export([start/0,

incoming/0, off_hook/0, on_hook/0, other_on_hook/0, connect/0,

init/1,

idle/2, ringing/2, connected/2, dial/2]).

-define(SERVER_NAME, phone).

start() ->

gen_fsm:start_link({local, ?SERVER_NAME}, ?MODULE, [], []).

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% API

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

incoming() -> gen_fsm:send_event(?SERVER_NAME, incoming).

off_hook() -> gen_fsm:send_event(?SERVER_NAME, off_hook).

on_hook() -> gen_fsm:send_event(?SERVER_NAME, on_hook).

other_on_hook() -> gen_fsm:send_event(?SERVER_NAME, other_on_hook).

connect() -> gen_fsm:send_event(?SERVER_NAME, connect).

...

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-98-320.jpg)

![The gen fsm of the fixed-line phone

✞

...

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

%% CALLBACKS

%% -------------------------------------------------------------------------------

init(Args) -> {ok, idle, []}.

idle(incoming, StateData) ->

io:format("Incoming calln"),

{next_state, ringing, StateData};

idle(off_hook, StateData) ->

io:format("The user is making a calln"),

{next_state, dialing, StateData}.

ringing(other_on_hook, StateData) ->

io:format("The peer closed the calln"),

{next_state, idle, StateData};

ringing(off_hook, StateData) ->

io:format("We answered the calln"),

{next_state, connected, StateData}.

connected(on_hook, StateData) ->

io:format("The call terminatedn"),

{next_state, idle, StateData}.

dial(on_hook, StateData) ->

io:format("The call terminatedn"),

{next_state, idle, StateData};

dial(connect, StateData) ->

io:format("The peer answered the calln"),

{next_state, connected, StateData}.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-99-320.jpg)

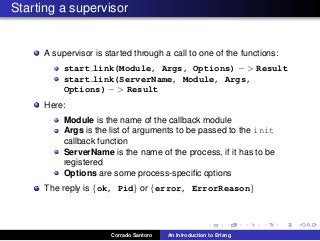

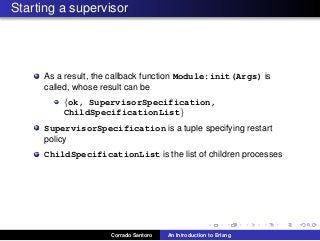

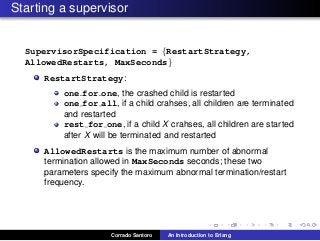

![Starting a supervisor

ChildSpecificationList = [{Id, {Mod, Fun, Args},

Restart, Shutdown, Type, ModuleList}]

Id, an id (atom) assigned to the child

{Mod, Fun, Args}, the specification of starting function of the

child module, with its args

Restart is the restart policy which can be transient,

temporary or permanent

Shutdown is the maximum time allowed between a termination

command and the execution of terminate function

Type is the process type, it can be worker or supervisor

ModuleList is the list of modules implementing the process;

this information is used during a software upgrade

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-104-320.jpg)

![The supervisor for mydb and phone

✞

-module(mysup).

-behaviour(supervisor).

-export([start/0, init/1]).

start() ->

supervisor:start_link({local, ?MODULE}, ?MODULE, []).

init(_Args) ->

SupSpecs = {one_for_one, 10, 1},

Child1 = {one, {reg_database, start, []}, permanent, 1000, worker, [reg_database]},

Child2 = {two, {phone, start, []}, permanent, 1000, worker, [phone] },

Children = [ Child1, Child2 ],

{ok, {SupSpecs, Children}}.

✡✝ ✆

Corrado Santoro An Introduction to Erlang](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-150303062108-conversion-gate01/85/Introduction-to-Erlang-105-320.jpg)