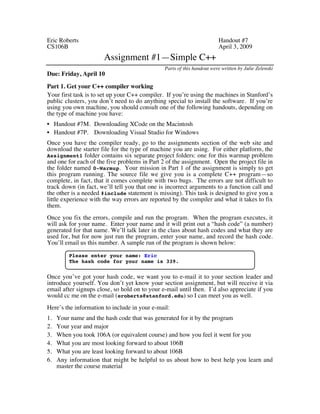

This document provides instructions for the first assignment in CS106B. It includes 5 problems to help students get familiar with C++ programming. The first problem has students fix bugs in a program that generates a hash code for a name. For the second problem, students write a program to display a histogram of exam scores. The third problem simulates coin flipping until getting 3 consecutive heads. The fourth problem implements Pascal's triangle recursively. The fifth problem converts integers to strings recursively. Students are asked to email their name, hash code, background, and feedback to the instructor.