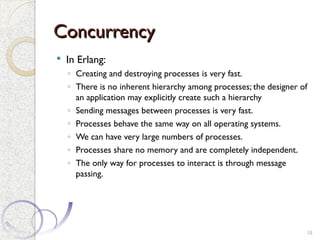

The document provides an overview of Erlang, a general-purpose concurrent programming language developed by Ericsson, highlighting its features such as lightweight processes, asynchronous message passing, and pattern matching. It explains various data structures like variables, tuples, lists, and functions, as well as concurrency mechanisms including process creation, message sending, and the client-server architecture. Additionally, it discusses module definitions and examples of how functions and guards can be used to structure code in Erlang.

![Lists

Lists

We create a list by enclosing the list elements in square

brackets and separating them with commas

◦ IfT is a list, then [H|T] is also a list, with head H and tail T.

◦ The vertical bar | separates the head of a list from its tail.

◦ [ ] is the empty list.

7

1> ThingsToBuy = [{apples,10},{pears,6},{milk,3}].

[{apples,10},{pears,6},{milk,3}]

2> [1+7,hello,2-2,{cost, apple, 30-20},3].

[8,hello,0,{cost,apple,10},3]

3> [H|T] = ThingsToBuy.

[{apples,10},{pears,6},{milk,3}]

4> H.

{apples,10}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-7-320.jpg)

![Modules

Modules

Modules are the basic unit of code in Erlang

◦ All Erlang functions belong to some particular module

◦ Some are exported and can be used outside

13

-module(math1).

-export([factorial/1]).

factorial(0) -> 1;

factorial(N) -> N * factorial(N-1).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-13-320.jpg)

![Modules

Modules

Example

◦ Compile and run

14

-module(geometry).

-export([area/1]).

area({rectangle, Width, Ht}) -> Width * Ht;

area({circle, R}) -> 3.14159 * R * R.

area({square, X}) -> X * X.

1> c(geometry).

{ok,geometry}

2> geometry:area({rectangle, 10, 5}).

50

3> geometry:area({circle, 1.4}).

6.15752](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-14-320.jpg)

![Case

Case

15

case Expression of

Pattern1 [when Guard1] -> Expr_seq1;

Pattern2 [when Guard2] -> Expr_seq2;

...

end

Example:

is_valid_signal(Signal) ->

case Signal of

{signal, _What, _From, _To} -> true;

{signal, _What, _To} -> true;

_Else -> false

end.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-15-320.jpg)

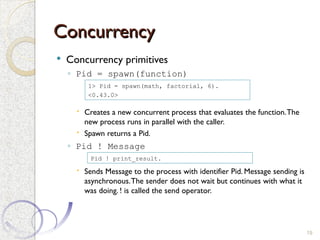

![Concurrency

Concurrency

Concurrency primitives

◦ receive ... end

Receives a message that has been sent to a process:

When a message arrives at the process, the system tries to match it against Pattern1 (with

possible guard Guard1);

if this succeeds, it evaluates Expressions1.

If the first pattern does not match, it tries Pattern2, and so on.

If none of the patterns matches, the message is saved for later processing, and the process

waits for the next message.

Even if the process to which the message is being sent has already terminated the system will

not notify the sender

However, as any messages not matched by receive are left in the mailbox, it is the

programmer‘s responsibility to make sure that the system does not fill up with such messages.

20

receive

Pattern1 [when Guard1] -> Expressions1;

Pattern2 [when Guard2] -> Expressions2;

...

end](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-20-320.jpg)

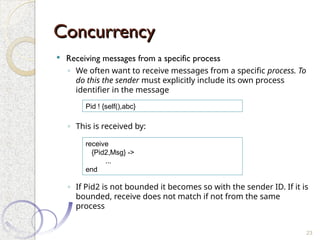

![Concurrency

Concurrency

21

-module(area_server).

-export([loop/0]).

loop() ->

receive

{rectangle, Width, Ht} ->

io:format("Area of rectangle is ~p~n" ,[Width * Ht]),

loop();

{circle, R} ->

io:format("Area of circle is ~p~n" , [3.14159 * R * R]),

loop();

Other ->

io:format("I don't know what the area of a ~p is ~n" ,[Other]),

loop()

end.

1> c(area_server).

{ok, area_server}

2> Pid = spawn( area_server,loop,[]).

<0.63.0>

3> Pid2 = spawn(fun area_server:loop/0).

<0.43.0>

4> Pid ! {rectangle, 3,4}.

Area of rectangle is 12

{rectangle,3,4}

5> Pid ! Pid ! {rectangle, 3,4}.

Area of rectangle is 12

{rectangle,3,4}

Area of rectangle is 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-21-320.jpg)

![Concurrency

Concurrency

22

-module(area_server).

-export([loop/0]).

loop() ->

receive

{rectangle, Width, Ht} ->

io:format("Area of rectangle is ~p~n" ,[Width * Ht]);

{circle, R} ->

io:format("Area of circle is ~p~n" , [3.14159 * R * R]);

Other ->

io:format("I don't know what the area of a ~p is ~n" ,[Other])

end,

loop().

1> c(area_server).

{ok, area_server}

2> Pid = spawn( area_server,loop,[]).

<0.63.0>

3> Pid2 = spawn(fun area_server:loop/0).

<0.43.0>

4> Pid ! {rectangle, 3,4}.

Area of rectangle is 12

{rectangle,3,4}

5> Pid ! Pid ! {rectangle, 3,4}.

Area of rectangle is 12

{rectangle,3,4}

Area of rectangle is 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-22-320.jpg)

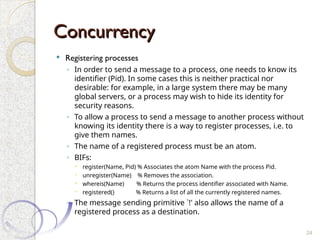

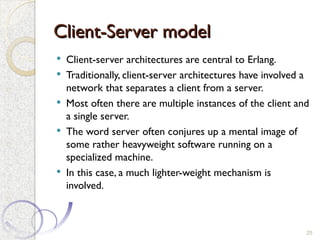

![Client-Server model

Client-Server model

For this to work, servers register themselves and clients lookup

Also, clients send their PID to receive the reply

27

-module(area_server_module).

-export([start/0,loop/0]).

start() ->

Pid = spawn (area_server_module, loop, []),

register(area_server, Pid).

loop() ->

receive

{From, rectangle, Width, Ht} ->

From ! Width * Ht;

{From, circle, R} ->

From ! 3.14159 * R * R;

Other -> loop()

end,

loop().

1> c(area_server_module).

{ok, area_server_module}

2> area_server_module:start().

true

3> area_server ! {self(), circle, 3}.

{<0.43.0>,circle,3}

4> receive Msg -> true end.

true

5> Msg.

28.274309999999996](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-27-320.jpg)

![Client-Server model

Client-Server model

For this to work, servers register themselves and clients lookup

Also, clients send their PID to receive the reply

28

-module(area_server_module).

-export([start/0,loop/0]).

start() ->

Pid = spawn (area_server_module, loop, []),

register(area_server, Pid).

loop() ->

receive

{From, rectangle, Width, Ht} ->

From ! Width * Ht;

{From, circle, R} ->

From ! 3.14159 * R * R;

Other -> loop()

end,

loop().

-module(area_server_client).

-export([rpc/2]).

rpc(Pid, Request) ->

Pid ! {self(), Request},

receive

Response -> Response

end.

1> area_server_client:rpc(area_server, {rectangle,6,8}).

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-28-320.jpg)

![Client-Server model

Client-Server model

For this to work, servers register themselves and clients lookup

Also, clients send their PID to receive the reply

29

-module(area_server_module).

-export([start/0,loop/0]).

start() ->

Pid = spawn (area_server_module, loop, []),

register(area_server, Pid).

loop() ->

receive

{From, rectangle, Width, Ht} ->

From ! {self(), Width * Ht};

{From, circle, R} ->

From ! {self(), 3.14159 * R * R};

Other -> loop()

end,

loop().

-module(area_server_client).

-export([rpc/2]).

rpc(Pid, Request) ->

Pid ! {self(), Request},

receive

{Pid, Response} -> Response

end.

1> area_server_client:rpc(area_server, {rectangle,6,8}).

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-29-320.jpg)

![Timeouts

Timeouts

Receive with timeout

◦ Sometimes a receive statement might wait forever for a message that

never comes.

◦ This could be for a number of reasons. For example:

There might be a logical error in our program,

or the process that was going to send us a message might have crashed

before it sent the message.

◦ To avoid this problem, we can add a timeout to the receive statement.

This sets a maximumTime that the process will wait to receive a message.

If no matching message has arrived within Time milliseconds of entering the receive

expression, then the process will stop waiting for a message with Pattern1 and evaluate

Expressions.

31

receive

Pattern1 [when Guard1] -> Expressions1;

after

Time -> Expressions

end](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-31-320.jpg)

![Timeouts

Timeouts

Implementing a Timer

33

-module(stimer).

-export([start/2, cancel/1, timer/2]).

start(Time, Fun) ->

spawn(stimer, timer,[Time, Fun]).

cancel(Pid) ->

Pid ! cancel.

timer(Time, Fun) ->

receive

cancel -> void

after

Time -> Fun()

end.

1> c(stimer).

{ok,stimer}

2> stimer:start(1000,

2> fun() ->

2> io:format("Fired ~n")

2> end

2> ).

<0.156.0>

Fired

3> P = stimer:start(30000, fun() -> io:format("Fired ~n") end).

<0.160.0>

4> stimer:cancel(P).

cancel](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-33-320.jpg)

![Timeouts

Timeouts

Implementing a Clock

34

-module(clock).

-export([start/2, stop/0]).

start(Time, Fun) ->

register(clock, spawn(fun() -> tick(Time, Fun) end)).

stop() -> clock ! stop.

tick(Time, Fun) ->

receive

stop -> void

after Time ->

Fun(),

tick(Time, Fun)

end.

3> clock:start(5000, fun() -> io:format("TICK p~n",

[erlang:now()]) end).

true

TICK {1204,494229,124000}

TICK {1204,494234,140000}

TICK {1204,494239,156000}

TICK {1204,494244,171000}

4> clock:stop().

stop](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-34-320.jpg)

![Shared data

Shared data

It is possible

◦ Using a server process

◦ Other processes write and read by communicating with the server process

◦ Mutual exclusion is guaranteed because server process handles requests

sequentelly

◦ Other mechanisms (e.g. semaphiores) can be built on top of this.

40

-module(shared).

-export([start/0, data_server/1]).

start() ->

register(shared, spawn(shared, data_server,[0]).

data_server(Val) ->

receive

{write, new_value} -> data_server(new_value);

{read , Pid} -> Pid ! Val,

data_server(Val)

end.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-40-320.jpg)

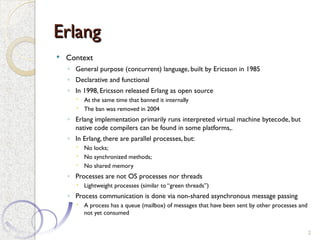

![Performance

Performance

41

-module(processes).

-export([max/1]).

%% max(N)

%% Create N processes then destroy them

%% See how much time this takes

max(N) ->

Max = erlang:system_info(process_limit),

io:format("Maximum allowed processes:~p~n" ,[Max]),

statistics(runtime),

statistics(wall_clock),

L = for(1, N, fun() -> spawn(fun() -> wait() end) end),

{_, T1} = statistics(runtime),

{_, T2} = statistics(wall_clock),

lists:foreach(fun(Pid) -> Pid ! die end, L),

io:format("Process spawn time=~p (~p) milliseconds~n" ,[T1, T2]),

U1 = T1 * 1000 / N, U2 = T2 * 1000 / N,

io:format("Avg per process=~p (~p) microseconds~n" ,[U1, U2]).

wait() ->

receive

die -> void

end.

for(N, N, F) -> [F()];

for(I, N, F) -> [F()|for(I+1, N, F)].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erlang-250109165755-061cb693/85/Reliable-and-Concurrent-Software-Erlang-41-320.jpg)