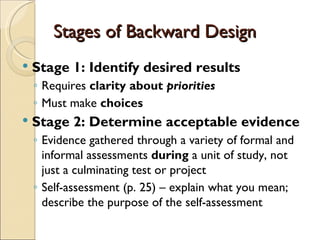

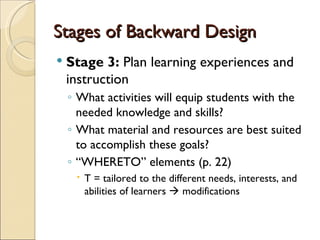

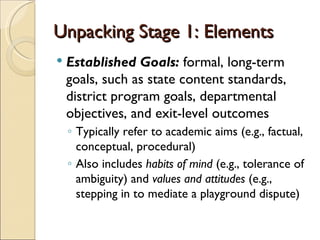

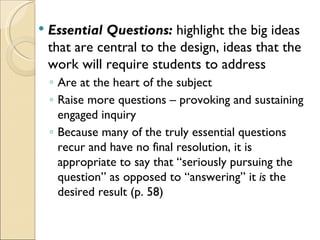

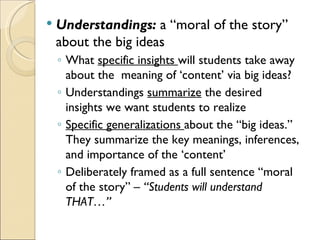

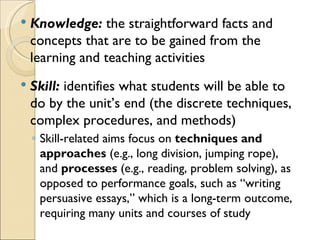

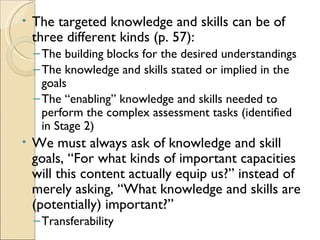

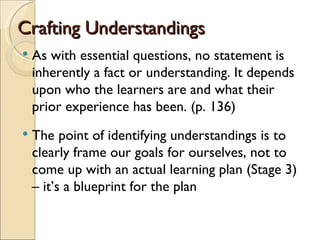

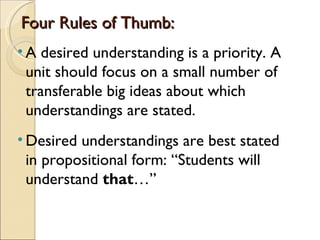

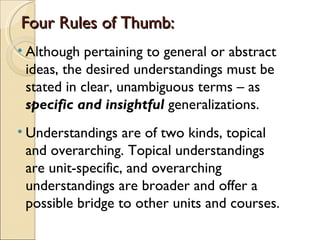

This document provides an introduction to the backward design process for curriculum development. It outlines the three stages of backward design: 1) identify desired results, 2) determine acceptable evidence, and 3) plan learning experiences and instruction. For stage 1, it discusses identifying goals, essential questions, understandings, knowledge, and skills. It emphasizes that the purpose is to be thoughtful about learning goals rather than just gaining technical skills. It also notes that the process is not always linear and the stages don't need to be followed strictly step-by-step.