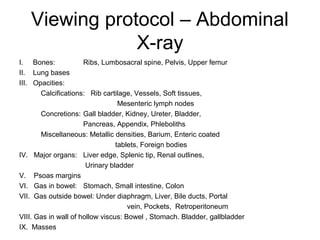

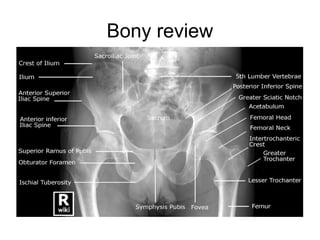

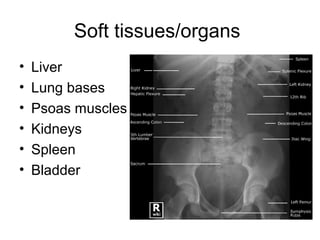

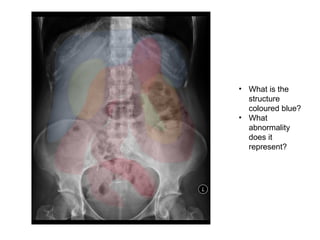

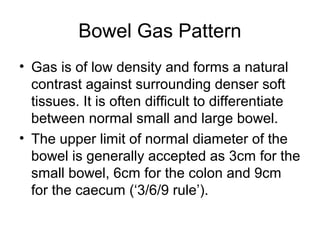

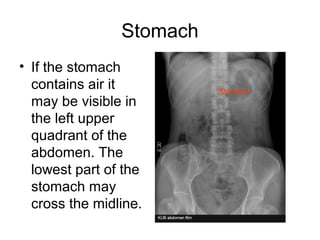

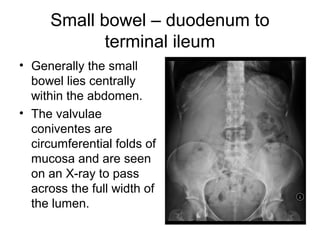

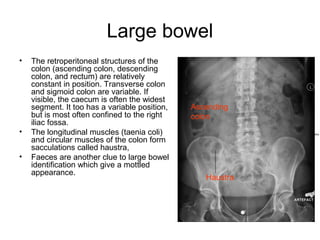

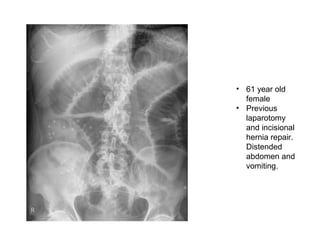

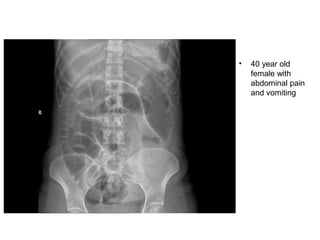

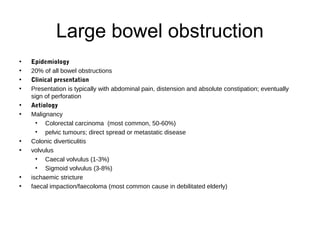

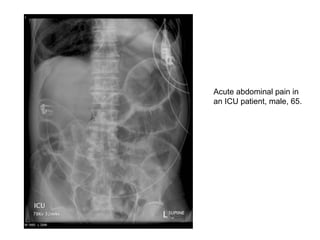

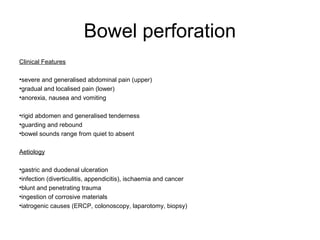

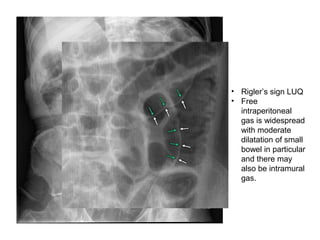

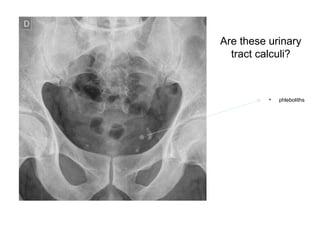

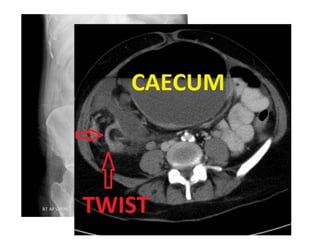

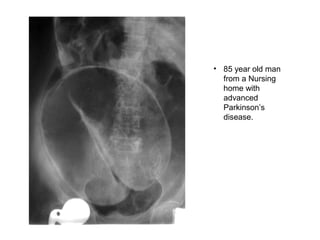

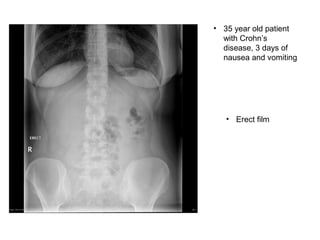

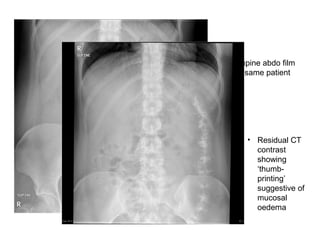

This document provides an overview of interpreting abdominal x-rays. It outlines the viewing protocol including examining bones, lungs, calcifications, organs and gas/bowel patterns. Common abnormalities are described such as small/large bowel obstructions, perforations and pneumoperitoneum. Specific cases are presented of patients with hernia, diverticulitis, Crohn's disease, and fecal impaction. While abdominal x-rays often have low yield, following a systematic approach and understanding normal anatomy and gas patterns is important for identifying any abnormalities present.