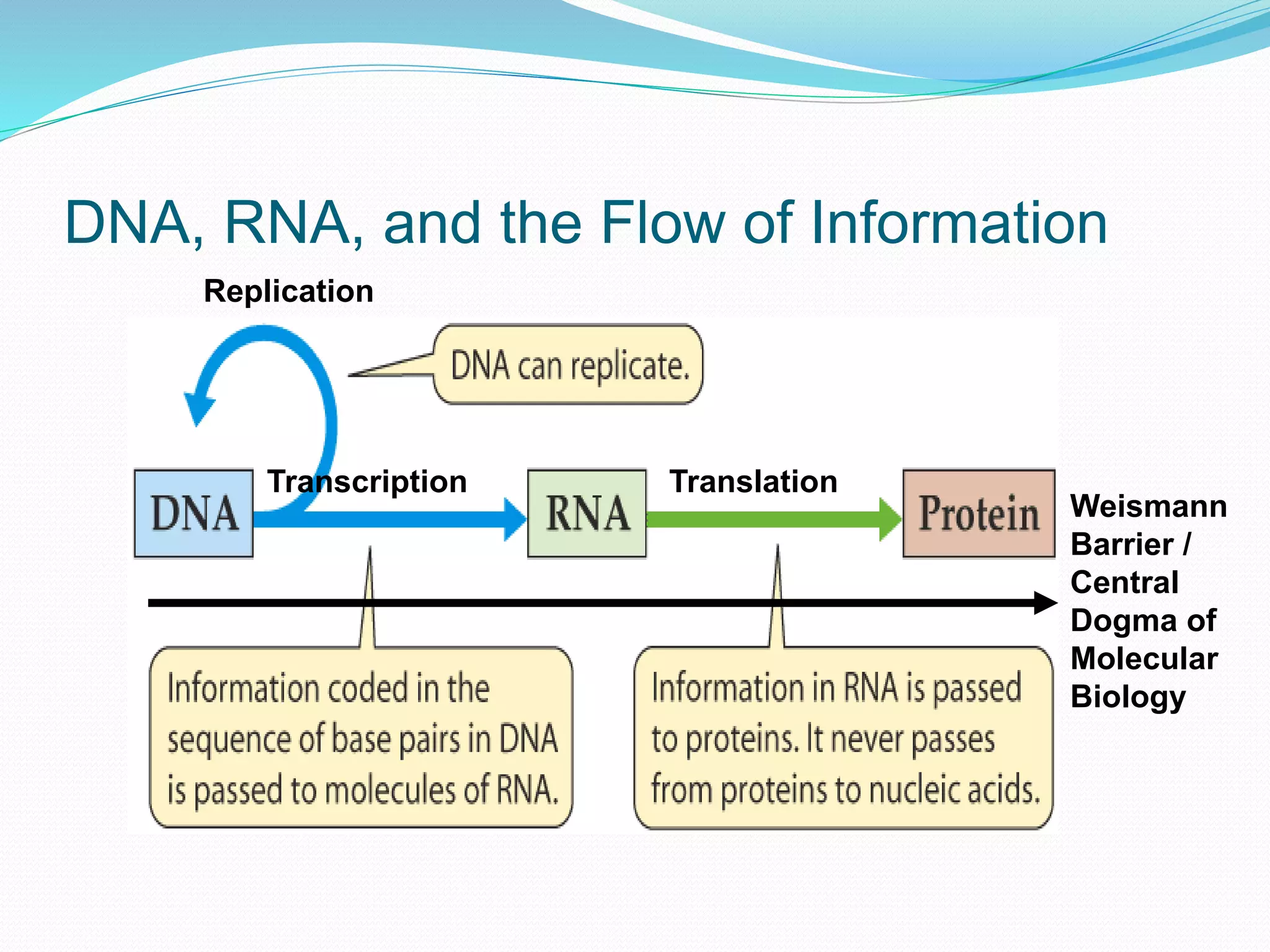

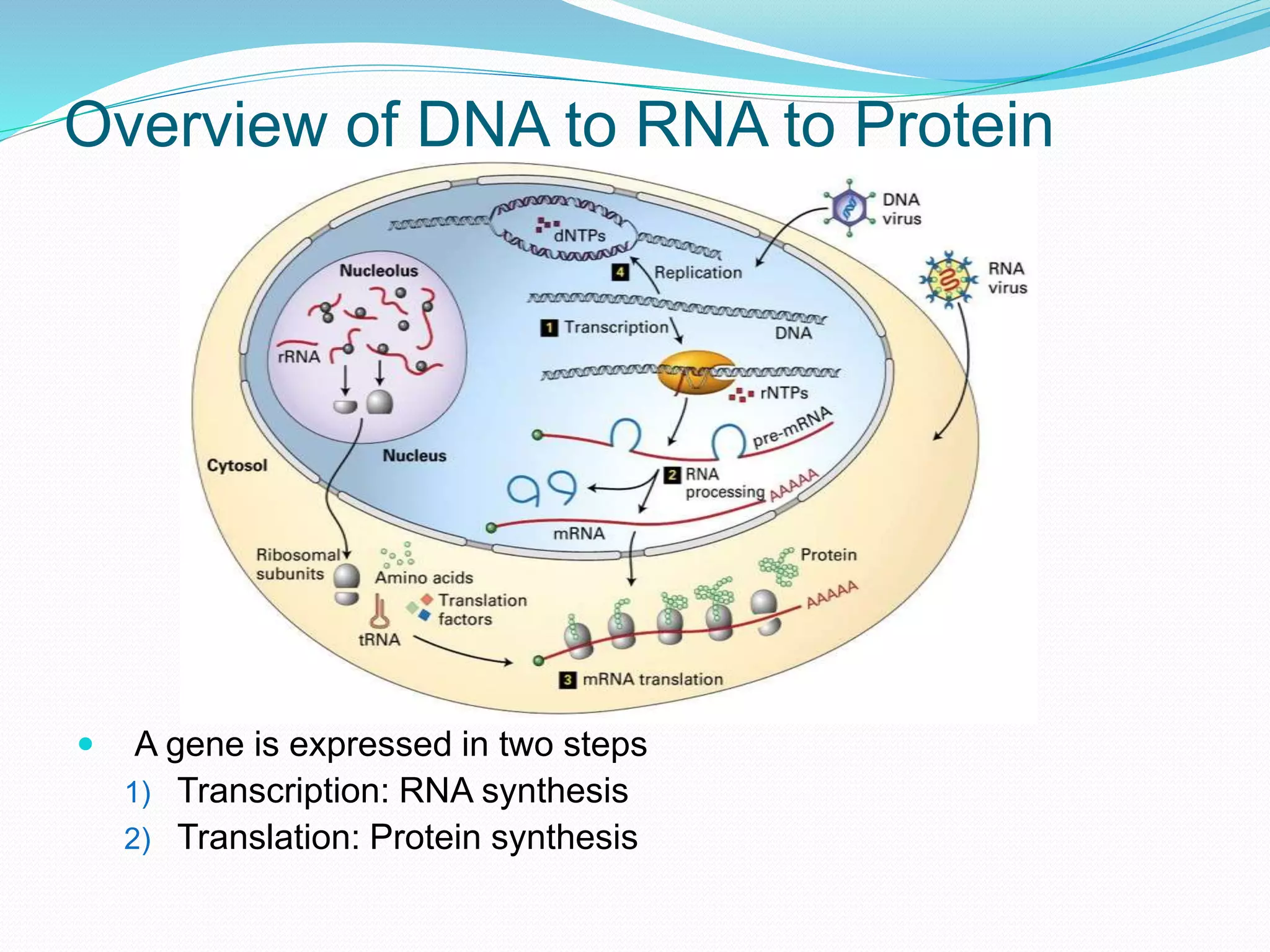

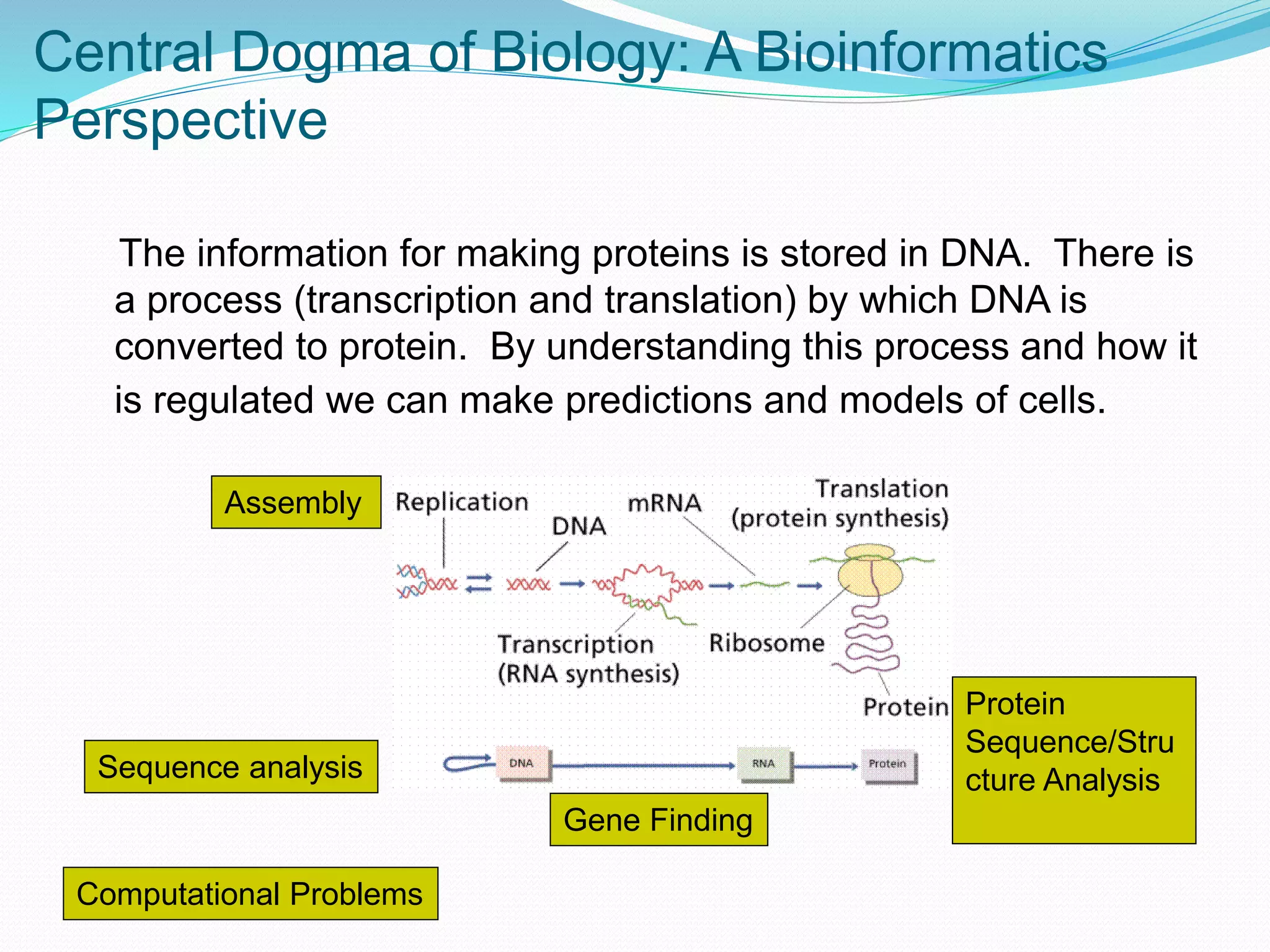

This document provides an overview of bioinformatics and related topics. It begins by defining bioinformatics as the use of computational techniques to understand biology. It then discusses the central dogma of biology, describing how DNA is transcribed into RNA and translated into protein. The document outlines common bioinformatics tasks like sequence analysis, databases, and modeling biological systems. It provides background on key biomolecules like DNA, RNA, and proteins and the information flow within biological systems.

![Three case studies

Mining –omics data

Predicting structural aspects of protein residues

Automated alphabet reduction for protein datasets

In all these three case studies we use the same

evolutionary learning system: BioHEL [Bacardit et al.,

09]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-85-2048.jpg)

![BioHEL BioHEL [Bacardit et al., 09] is an evolutionary

learning system that applies the Iterative Rule

Learning (IRL) approach

Designed explicitly to deal with noisy large-scale

datasets

IRL was first used in EC by the SIA system

[Venturini, 93]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-86-2048.jpg)

![Functional Network Reconstruction

for seed germination Microarray data obtained from seed tissue of Arabidopsis

Thaliana

122 samples represented by the expression level of

almost 14000 genes

It had been experimentally determined whether each of

the seeds had germinated or not

Can we learn to predict germination/dormancy from the

microarray data?

[Bassel et al., 2011]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-97-2048.jpg)

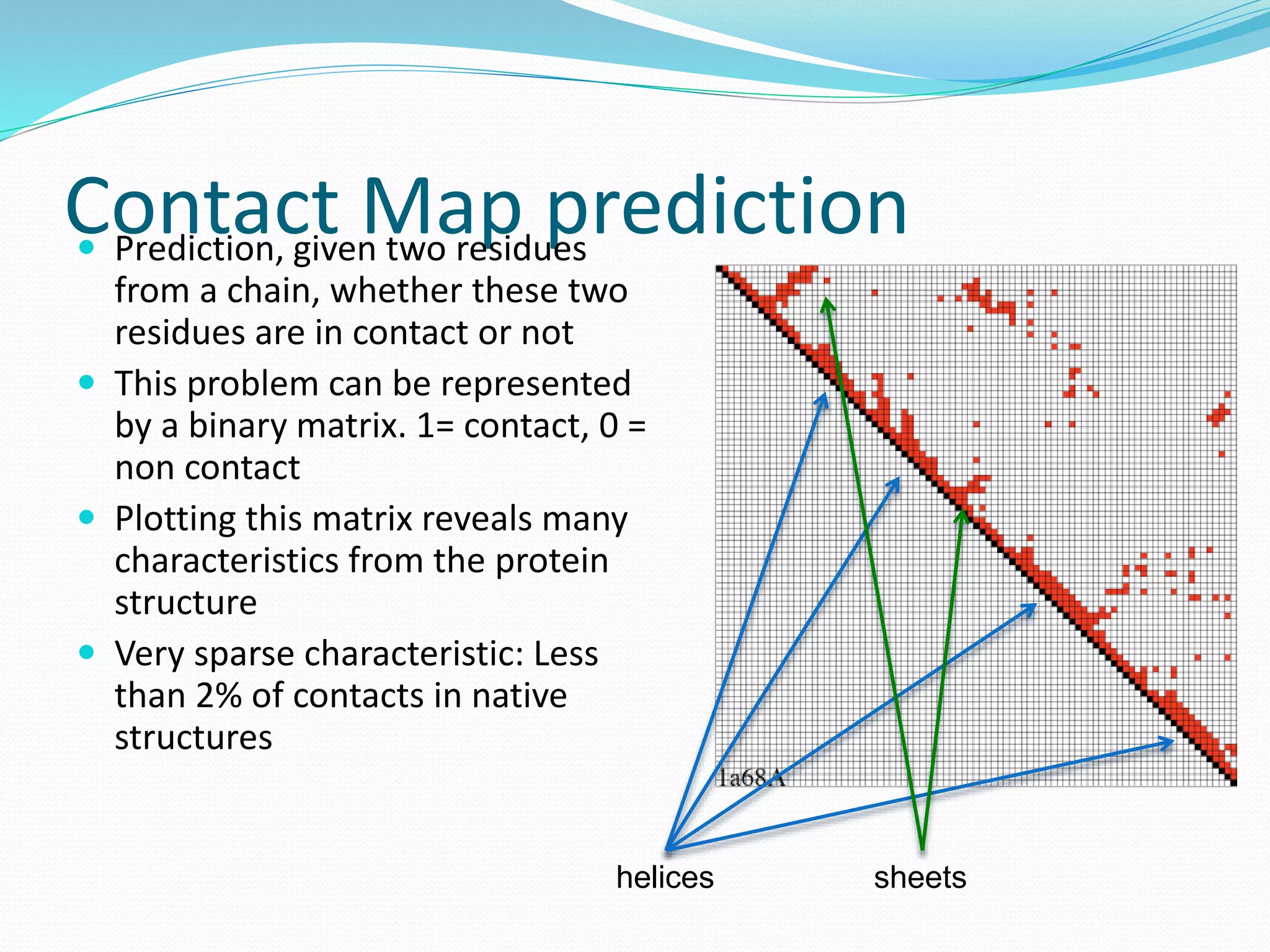

![Steps for CM prediction (Nottingham

method)

1. Prediction of

Secondary structure (using PSIPRED)

Solvent Accessibility

Recursive Convex Hull

Coordination Number

2. Integration of all these predictions plus other sources of

information

3. Final CM prediction (using BioHEL)

Using BioHEL [Bacardit et al., 09]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-115-2048.jpg)

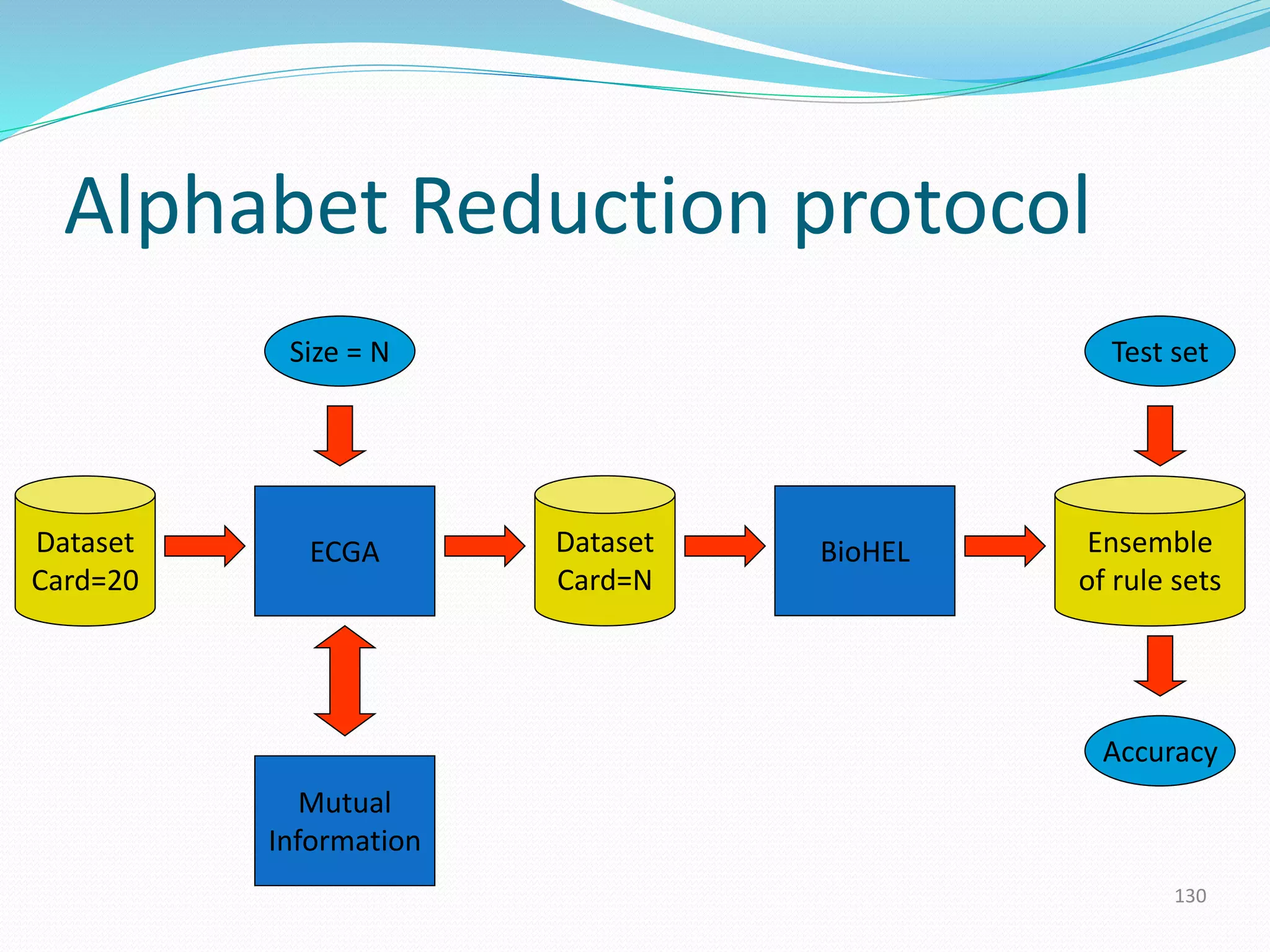

![Target for reduction: the primary sequence

The primary sequence of a protein is

an usual target for such simplification

It is composed of a quite high cardinality

alphabet of 20 symbols, which share

commonalities between them

One example of reduction widely used in

the community is the hydrophobic-polar

(HP) alphabet, reducing these 20 symbols

to just two

HP representation usually is too simple,

too much information is lost in the

reduction process [Stout et al., 06]

Can we automatically generate these

reduced alphabets and tailor them to

the specific problem at hand?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-128-2048.jpg)

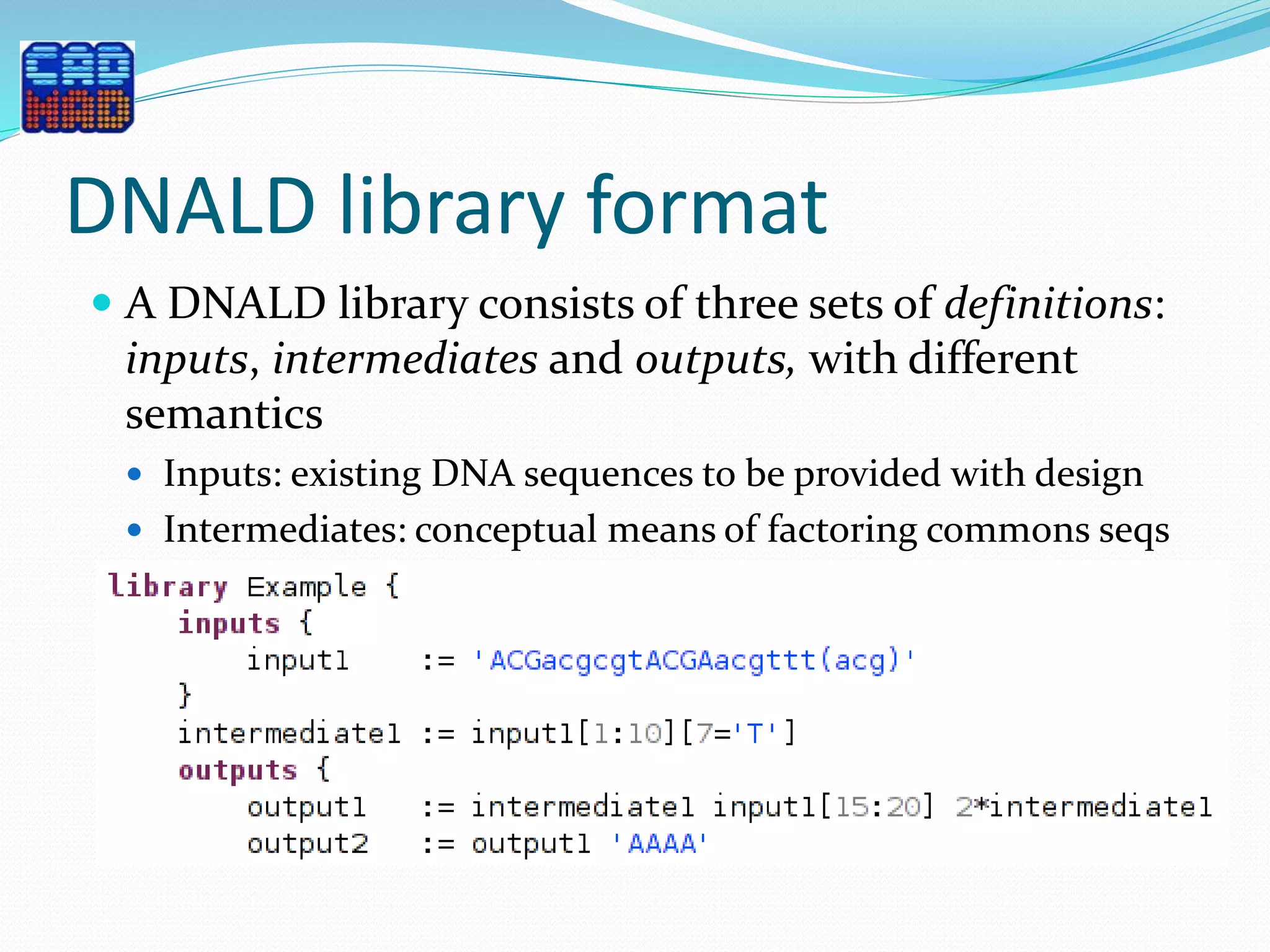

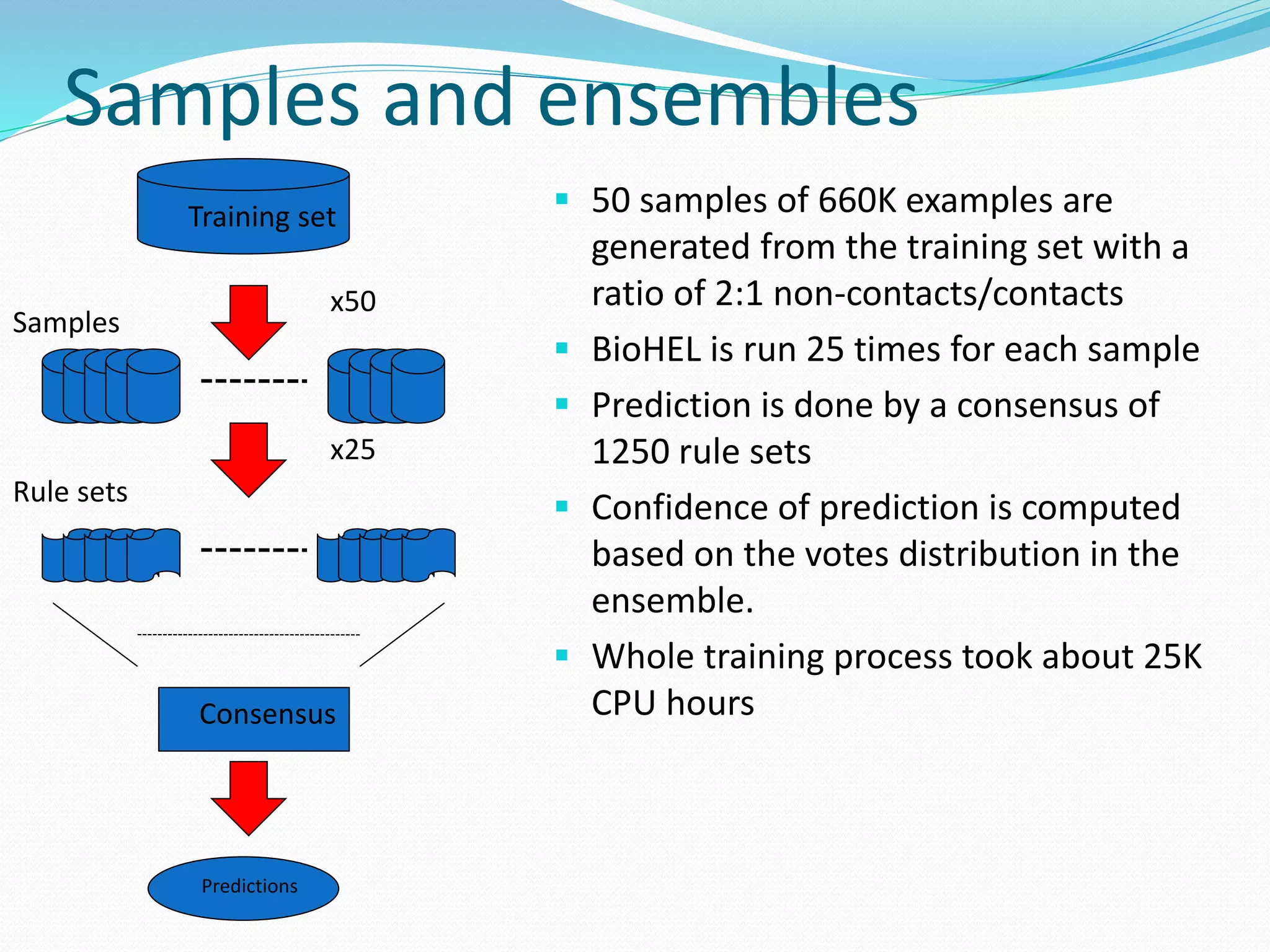

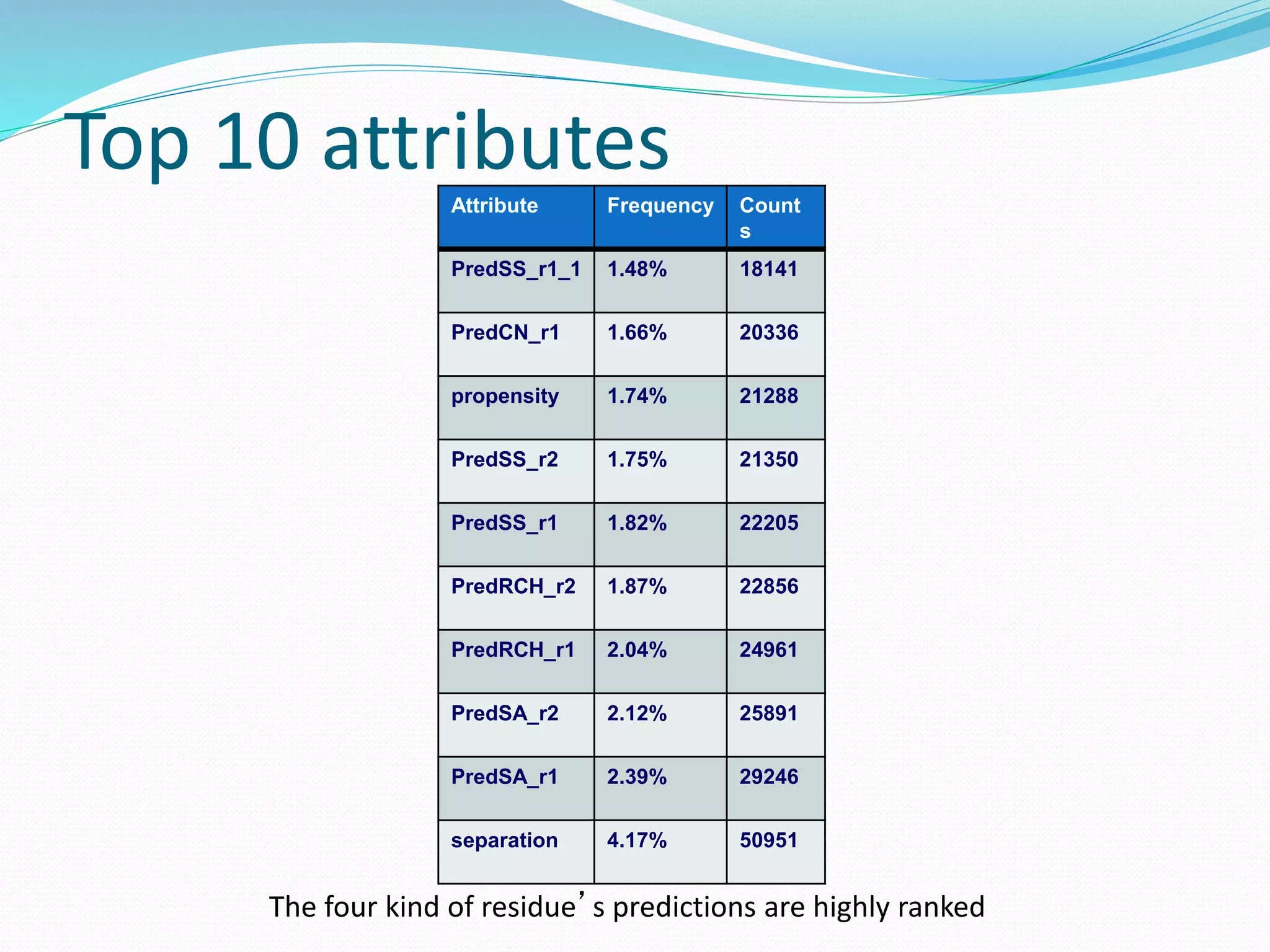

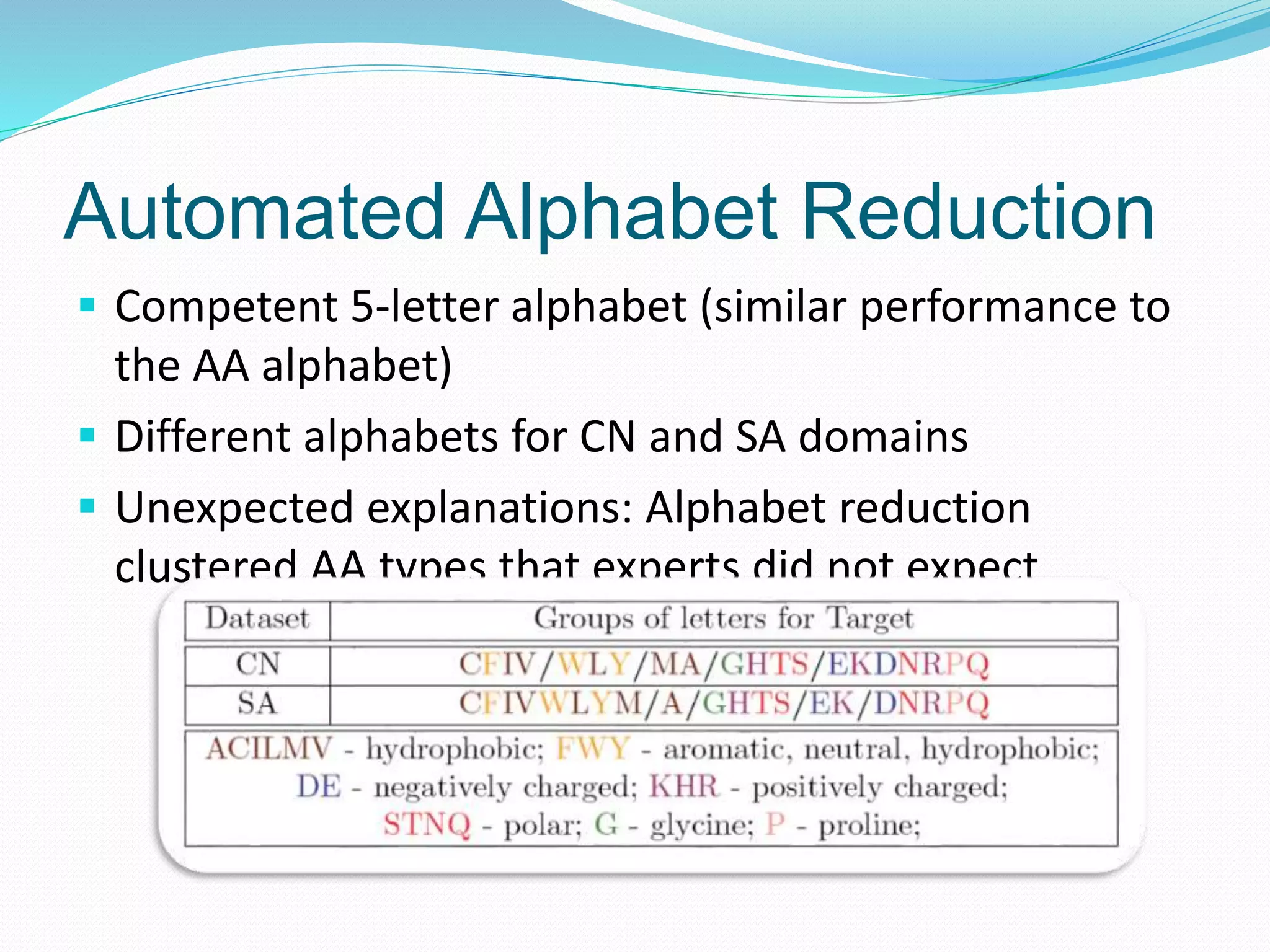

![Automated Alphabet Reduction

[Bacardit et al., 09]

• We will use an automated information theory-driven

method to optimize alphabet reduction policies for PSP

datasets

• An optimization algorithm will cluster the AA alphabet into

a predefined number of new letters

• Fitness function of optimization is based on the Mutual

Information (MI) metric. A metric that quantifies the

interrelationship between two discrete variables

– Aim is to find the reduced representation that maintains as much

relevant information as possible for the feature being predicted

• Afterwards we will feed the reduced dataset into a

learning method to verify if the reduction was proper](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-129-2048.jpg)

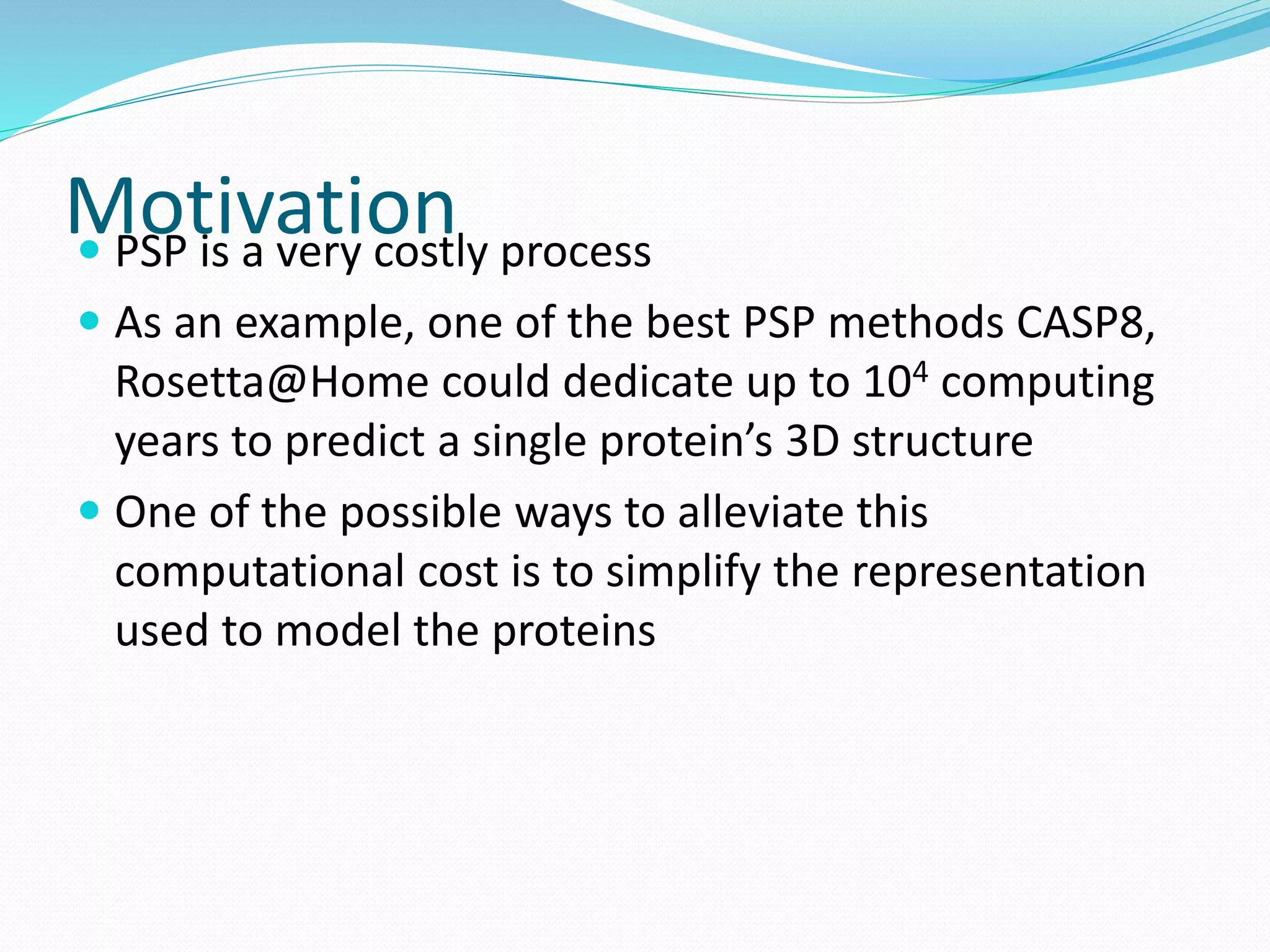

![Automated Alphabet Reduction

Our method produces better reduced alphabets than other

reduced alphabets from the literature and than other expert-

designed ones

Alphabets

from the

literature

Expert

designed

alphabets

Alphabet Letters CN acc. SA acc. Diff. Ref.

AA 20 74.0±0.6 70.7±0.4 --- ---

Our method 5 73.3±0.5 70.3±0.4 0.7/0.4 [Bacardit et al., 07]

WW5 6 73.1±0.7 69.6±0.4 0.9/1.1 [Wang & Wang, 99]

SR5 6 73.1±0.7 69.6±0.4 0.9/1.1 [Solis & Rackovsky, 00]

MU4 5 72.6±0.7 69.4±0.4 1.4/1.3 [Murphy et al., 00]

MM5 6 73.1±0.6 69.3±0.3 0.9/1.4 [Melo & Marti-Renom, 06]

HD1 7 72.9±0.6 69.3±0.4 1.1/1.4 [Bacardit et al., 07]

HD2 9 73.0±0.6 69.3±0.4 1.0/1.4 [Bacardit et al., 07]

HD3 11 73.2±0.6 69.9±0.4 0.8/0.8 [Bacardit et al., 07]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-132-2048.jpg)

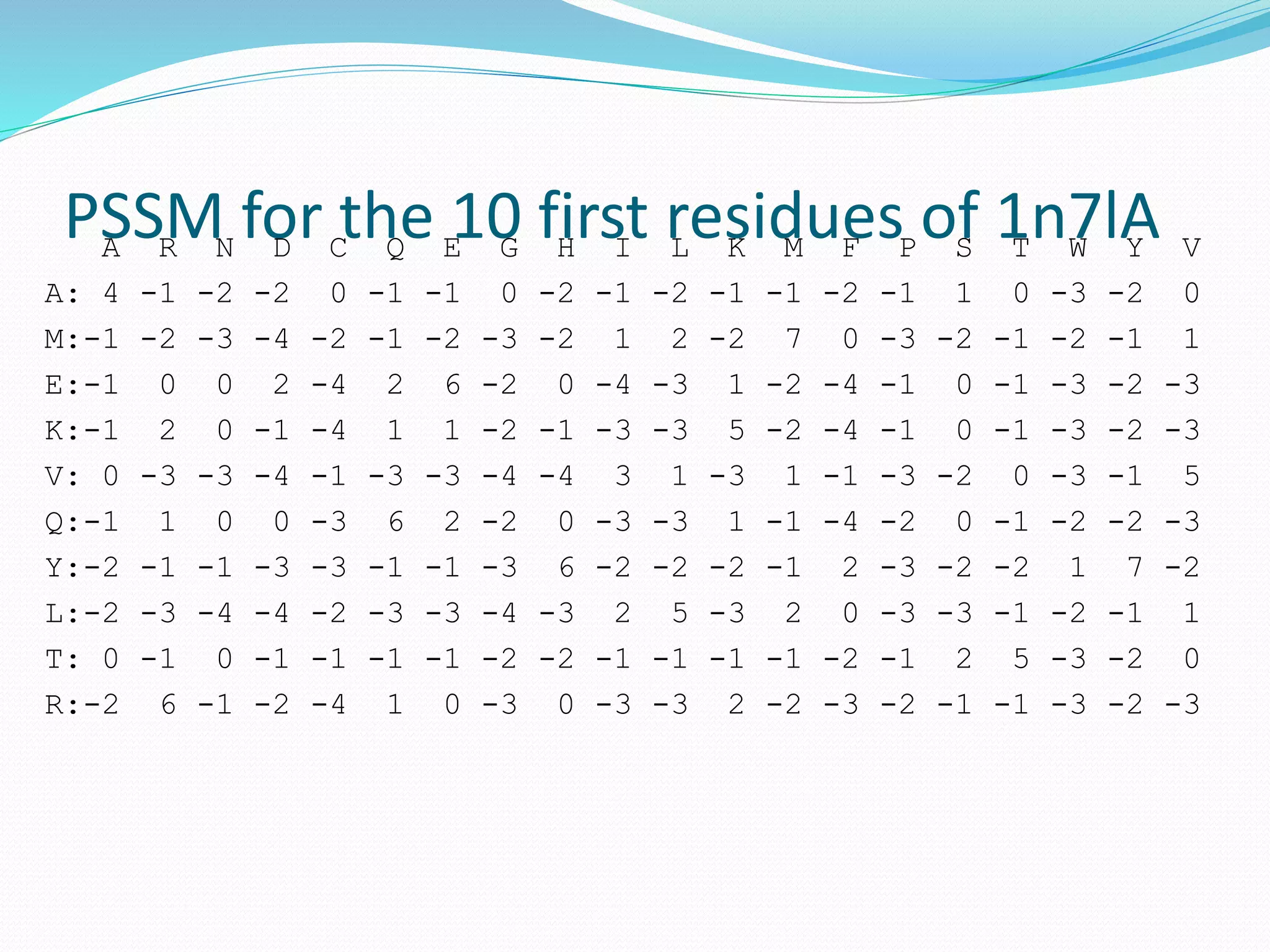

![Efficiency gains from the alphabet

reduction

We have extrapolated the reduced alphabet to the much

larger and richer Position-Specific Scoring Matrices (PSSM)

representation

Accuracy difference is still less than 1%

Obtained rule sets are simpler and training process is much

faster

Performance levels are similar to recent works in the literature

[Kinjo et al., 05][Dor and Zhou, 07]

Won the bronze medal of the 2007 Humies awards](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introduction-170331154845/75/Introduction-133-2048.jpg)