This research paper explores the crucial role of emotional intelligence (EI) in the work of interpreters, emphasizing its significant impact on managing clients' expectations and job satisfaction. The study employs both quantitative and qualitative methods, revealing that interpreters generally possess an average level of EI, but those with higher EI traits perform better under pressure. The findings suggest that incorporating EI into interpreter training could enhance performance and well-being in interpreting settings.

![18

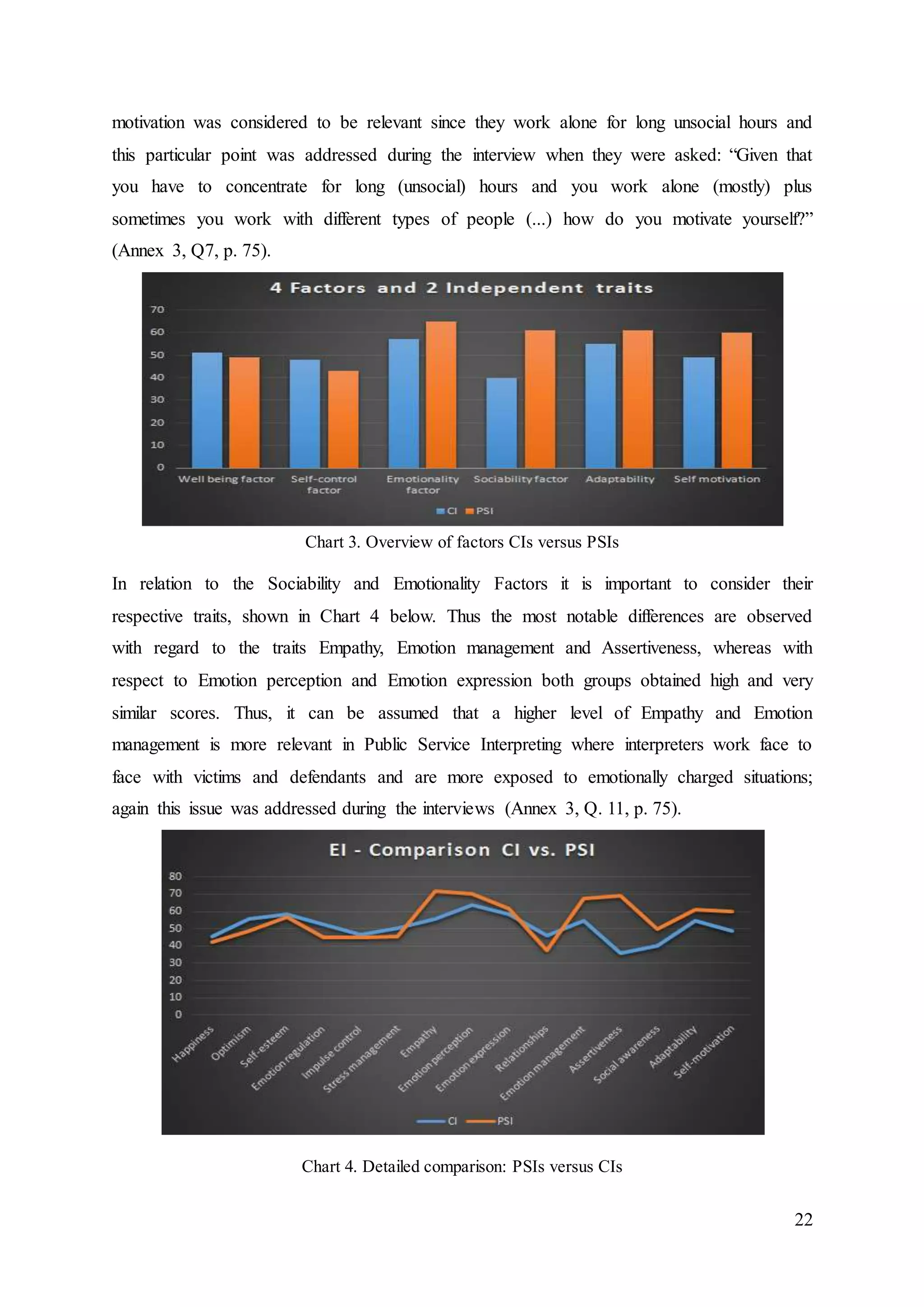

PSIs: “Given that you have to concentrate for long (unsocial) hours and you work alone

(mostly) plus sometimes you work with different types of people (defendants who may be

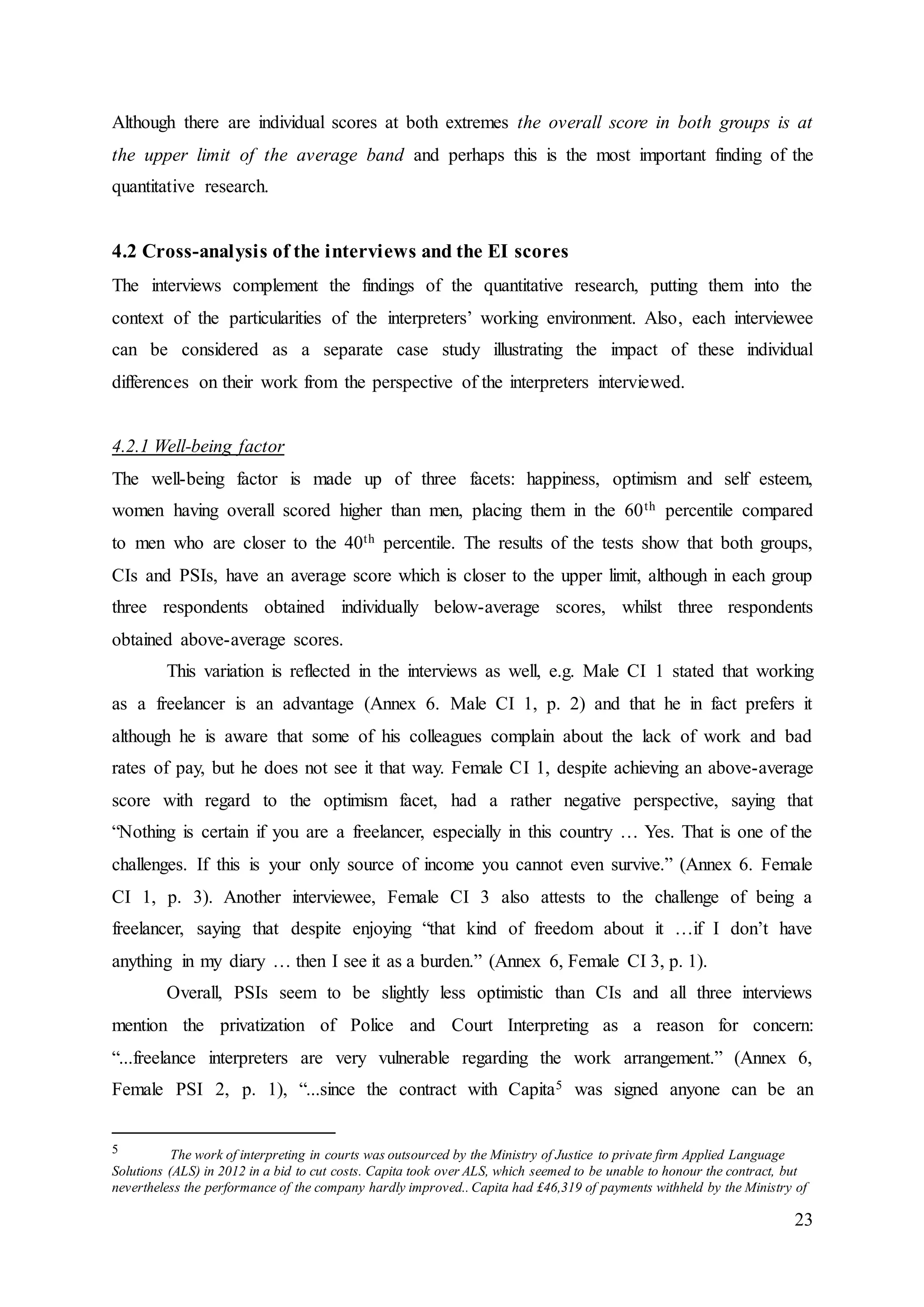

drunk, frustrated or victims who are distressed)... how do you motivate yourself?”

More importantly the questions were designed after the quantitative data was collected and

they are grouped thematically around certain EI traits in which interpreters generally scored

higher during the first (quantitative) stage of the research. The majority of the questions are

open-ended, especially the introductory ones meant to break the ice and encourage the

interviewee to speak freely; however, some probing questions were introduced as well to help

guide the conversation, as in the example below:

“As a freelance interpreter how stable and/or predictable would say your work environment

is? Is this a problem for you or do you enjoy it?”

Although the questions were sent to the interviewees prior to the interviews (simply because

the majority explicitly asked for them) it was clearly explained in the email that they would

be used as prompts and that they were not required to think of potential answers in advance.

The six interviews were held either face to face or via Skype depending on each interviewee's

location and availability. The interviewees were native speakers of German, Romanian,

Latvian, English and Chinese. All the interviews were carried out in English, even when the

author shared the same mother tongue with two of the interviewees. Thus, it was the author’s

intention to distance herself from this cultural proximity and to ensure a constant level of

objectivity.

3.4 Use of interview material

The interviews covered six hours in total and they ranged between 45 minutes and 1 hour and

30 minutes and they were transcribed in full in English with some minor corrections to

improve clarity. These corrections are clearly signalled by square brackets […]. The full

transcriptions are contained in the accompanying CD (Annex 6). To ensure anonymity direct

quotes are referenced with the acronym of CI or PSI and female or male depending on the

case and a number: 1, 2 or 3, which is the order in which the EI test was taken, and they can

be easily cross-referenced with the table showing the EI scores at Annex 5. When text has

been left out from a direct quote, this is indicated with (…).

The information (personal details) contained in the final section of the EI test is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dissertationdianasingureanu-160627111727/75/Interpreters-and-Emotional-Intelligence-How-do-we-use-it-and-why-does-it-matter-18-2048.jpg)

![25

effectively (Annex 2, Sample report, p. 60). The fact that all six interviewees had a self-

esteem score above average was reflected in their statements, because they all confirmed that

they are not influenced by their colleagues’ opinions or the end users’ opinions when it comes

to their performance: “When it comes to feedback from my colleagues it doesn’t matter

because I think I can assess that myself well enough” (Annex 6, Male CI 1, p. 5); “I don’t

expect people to come and tell me all the time how wonderful it was. I think you need to have

a thicker skin than that because people are usually quite happy to criticise and not so keen on

praising” (Annex 6, Female CI 3, p. 4), “If I don’t understand something I’m not afraid to say

‘This is the interpreter, could you repeat that’ and whenever I did that I was treated with

respect” (Annex 6, Male PSI 5, p. 5); “I believe I have the right to make mistakes [if] you

alert immediately the parties, that’s fine.” (Annex 6, Female PSI 2, p. 6).

4.2.2 Self-control factor

This Factor describes how well respondents regulate external pressure, stress, and impulses

and it contains the facets of Emotion regulation, Impulse control and Stress management

(Annex 2. Sample report, pp. 60-61).

The overall score of the respondents for the self-control factor was 48 for CIs and

43.17 for PSIs with men scoring overall 6.17 more than women and in particular 12.67 more

when it comes to Impulse control. With regard to the six interpreters who were interviewed,

two of them had an above-average score in self-control (Male CI 1 and Female PSI 2), two

had an average score (Female CI 1 and Female PSI 1) and two had a below-average score

(Female CI 3 and Male PSI 2). All three interpreters who had a below-average score in trait

Emotion regulation gave an example when either they had their own personal reaction to a

work related situation: “I felt sorry for her and responsible and I paid for her travel and food

because she had not been offered anything at the time… at the end of day she was a human

being and I think she deserved to be treated accordingly.” (Annex 6, Female PSI 1, p. 3) or

they somehow intervened in the interpreting session because either it was considered to be in

the interest of the patient: “I just turned and explained to the officer: ‘This lady is extremely

ill and you must take her to a psychiatric unit immediately.” (Annex 6, Male PSI 2, p. 3) or in

the interest of the client: “It was not my role but…in the break I spoke to the Union

representative saying that the Spanish had been mistranslated and they were going round in

circles. I couldn’t let it go. It was in the interest of the client… It’s a matter of discretion… It

can backfire.”(Annex 6, Female CI 3, p. 3). Emotion regulation measures how someone

controls his or her feelings and internal states in the short, medium and long term and the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dissertationdianasingureanu-160627111727/75/Interpreters-and-Emotional-Intelligence-How-do-we-use-it-and-why-does-it-matter-25-2048.jpg)

![27

she considered herself “one of the lucky ones” because “the job didn’t get to” her (Annex 6,

Female PSI 1, p. 4) implying that other interpreters could be more affected by similar

circumstances. She also concluded at the end of the interview, “Overall in my experience in

terms of the level of empathy needed I think the job is more female oriented” (Annex 6,

Female PSI 1, p. 4).

Also, Male CI 1 stated, “I can really put myself in someone else’s shoes, but really,

always for both sides, which is ideal, I think, for an interpreter,” and then explains that this is

something he took away from his Emotional Intelligence Report and he had never thought

about it until then: “Empathy is important or, better said, I think it plays a role in me doing a

good job, the fact that I empathize with people” (Annex 6, Male CI 1, p. 7). He also gave one

example where a seemingly uncooperative colleague kept leaving the booth when it wasn’t

her turn, but he then justifies her behaviour, saying that she was “too fragile” and that this

was her way of coping with the stressful situation (Annex 6, Male CI 1, p. 5), which shows

his ability to understand her emotions (trait Emotion Perception) and his capacity to take her

view into account (trait Empathy).

Another interviewee who had an extremely high score in trait Empathy, Male PSI 2,

stated that Empathy “is extremely important,” adding: “I don’t think that in PSI in the

majority of cases you can manage without at least an average amount of Empathy” (Annex 6,

Male PSI 2, p. 2). He also gave three examples in a medical setting where he used Empathy

in his work; in two cases he was interpreting for psychiatric patients and he explained that it

was necessary “to build some sort of rapport” with the person being treated because “if they

are frightened you have to be very patient otherwise you are making it worse” plus “the

psychiatrist is depending on your interpretation to find out what the treatment of this person

should be” (Annex 6, Male PSI 2, p. 2), which shows his ability to understand the viewpoint

of the psychiatrist as well. Explaining why this is more important in a medical setting he

elaborates further: “...apart from the content of what they [patients] say – this is why you

need empathy – the way they say it it’s different from normal and that’s important” (Annex 6,

Male PSI 2, P. 3). In the third case he had to tell two young parents that their baby had died

and took a moment to offer his condolences as an interpreter (Annex 6, Male PSI 2, p. 5)

demonstrating not only his ability to perceive the parents’ emotions (Emotion Perception) and

relate to them (trait Empathy), but also his ability to express his emotion in offering the

condolences (trait Emotion Expression), which makes unsurprising the fact that he obtained a

high score (99) in all these three traits. In another example, he was doing telephone

interpreting to help repatriate the bodies of the pilots who had died in a plane crash which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dissertationdianasingureanu-160627111727/75/Interpreters-and-Emotional-Intelligence-How-do-we-use-it-and-why-does-it-matter-27-2048.jpg)

![35

5.3 Emotionality factor

Overall, women scored considerably higher than men in both Emotion perception and

Emotion expression, which is line with previous research showing that “women do have an

edge over men” (Goleman, 2011) when it comes to Emotional Intelligence. Emotion

perception and Emotion expression would undoubtedly assist an interpreter to decode non-

verbal communication and to convey meaning, as is rightly pointed out on the AIIC website.

However, it is important to consider that out of the six interviewees four were female and two

male, and the two males obtained particularly high scores, both overall (Male CI 1 – 85 and

Male PSI 2 – 92) and in the Emotionality factor (91 and 99 respectively), so perhaps they are

not typical in this sense and they may not necessarily be considered to be representative of

the male population of interpreters in general. Nevertheless this may explain why they dwell

more on the topic of emotions. like Male CI 1: “it [empathy] is important when there are

emotions to convey and you are meant to be, as the conveyer of emotions, authentic” (Annex

6, Male CI 1, p. 6) or why Male PSI 2 gave so many examples of when he used Empathy.

Throughout the interviews all the interpreters, either when specifically prompted or when

digressing from another topic, remarked on the importance of conveying emotions in their

work and therefore the need to have the ability to express emotions. Of course this

presupposes that to begin with they are able to perceive the emotions they are meant to

convey which implies having a good level of Emotion perception, and indeed all the

interpreters interviewed had an extremely high score in trait Emotion Perception (EI results

table at Annex 5). So, not only do these interpreters possess the abilities to perceive and

express emotion but they also believe that they are useful and necessary in their work: “I can

put myself into the place of the mother who will lose her child because health care is not

sufficient in her country and then in the place of the politician who speaks about the lack of

funds and the corruption and then I can understand that side as well.” (Annex 6, Male CI 1, p.

6), thus explaining why being equally empathetic to all parties involved wouldn’t clash with

the impartiality rule that all Conference interpreters must observe in accordance with the

AIIC Code of Ethics.

Similarly, Female PSI 2, who had a high score (99) in both Emotion perception and

Emotion expression, when asked if it happens for defendants or victims to be confused about

her role as an interpreter she replied: “It happens all the time. Your typical victim or

defendant will immediately think you are their mother, father, friend, chaperone that they can

treat you in a way that makes you uncomfortable; you hardly ever come across anyone who](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dissertationdianasingureanu-160627111727/75/Interpreters-and-Emotional-Intelligence-How-do-we-use-it-and-why-does-it-matter-35-2048.jpg)

![45

References

AIIC Code of Professional Ethics (2012). [Online] Available at: http://aiic.net/page/54/code-of-professional-

ethics/lang/1(Accessed:23 May 2014).

AIIC Private Market Sector Standing Committee (2012). Conference and remote interpreting: a new turning

point? [Online] Available at: http://aiic.net/page/3590/conference-and-remote-interpreting-a-new-turning-

point/lang/1 (Accessed:10 August 2014).

Besson C., Graf D., Hartung I., KropfhäusserB. and Voisard S. (2012). The importance of non-verbal

communication in professional interpretation. [Online] Available at: http://aiic.net/page/1662/the-importance-of-

non-verbal-communication-in-professional-interpretation/lang/1 [Accessed:10 August 2014].

Bii, P. K., Lucas, O., Mwengei O.K.B,Koskey, N., Korir, E. and Yano, E. M. (2012). A determinant of

Management’s Emotional Intelligence Competency. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and

Policy Studies, Vol. 3, Issue 6, December, pp. 807–811. [Online] Available at:

http://jeteraps.scholarlinkresearch.org/articles/Age.pdf (Accessed : 1 July 2014).

Bontempo, K. and Napier, J. (2011).Evaluating emotional stability as a predictor of interpreter competence and

aptitude for interpreting. Interpreting, 13(1), pp. 85-105.

Bontempo, K., Napier, J., Hayes, L. and Brashear, V. (2014). Does personality matter? An international study of

sign language interpreter disposition. The International Journal for Translation & Interpreting Research, 6 (1).

[Online] Available at: http://trans-int.org/index.php/transint/article/view/321/154 (Accessed: 20 May 2014).

Chmiel, A. (2010). Interpreting Studies and psycholinguistics: a possible synergy effect. In: D. Gile, G. Hansen

and N.K. Pokorn, eds. (2010) Why Translation Studies Matters. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing

Company, pp. 223-236.

Davey G. (2005). The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Psychology, London: HodderArnold Publishers.

Freudenthaler, H. H., Neubauer, A. C., Gabler, P., Scherl, W. G. and Rindermann, H. (2008). Testing and

validating the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue) in a German-speaking sample. Personality

and Individual Differences, 45, pp. 673-678. [Online] Available at:

http://www.psychometriclab.com/admins/files/Freudenthaler%20et%20al.%20TEIQue.pdf (Accessed: 7 June

2014).

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Goleman, D. (1996). Emotional Intelligence. Why it can matter more than IQ. London: Bloomsbury Publishing

PLC.

Goleman, D. (2011). Are Women More Emotionally Intelligent Than Men? The Brain and Emotional

Intelligence. [Online] Available at: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-brain-and-emotional-

intelligence/201104/are-women-more-emotionally-intelligent-men (Accessed: 1 July 2014).

Hale, S. B. (2007). Community Interpreting. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hof, M. R. (2013). The right Stuff? The AIIC Blog, [Online] Available at: http://aiic.net/page/6529/-the-right-

stuff/lang/1#authors_bio (Accessed: 27 May 2014).

Hubscher-Davidson, S (2007), An Empirical Investigation into the Effects of Personality on the Performance of

French to English Student Translators. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Bath.

Hubscher-Davidson, S. (2009). Personal diversity and diverse personalities in translation: a study of individual

differences Perspectives: Studies in Translatology, 17 (3), pp. 175–192., [Online] Available at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09076760903249380 (Accessed: 1 May 2014).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dissertationdianasingureanu-160627111727/75/Interpreters-and-Emotional-Intelligence-How-do-we-use-it-and-why-does-it-matter-45-2048.jpg)

![46

Hubscher-Davidson, S. (2013). Emotional Intelligence and Translation Studies. A New Bridge. Meta: Journal

des Traducteurs. 58 (2), pp. 324–346.

IoL Educational Trust (2010). Diploma in Public Service Interpreting. Handbook for candidates.

[Online]Available at: http://www.iol.org.uk/qualifications/DPSI/Handbook/DPSIHB11.pdf (Accessed:1 July

2014).

Jaeger, A. (2003). Job competencies and the curriculum: an enquiry into emotional intelligence in graduate

professional education. Research in Higher Education.44(6): pp. 615-639.

Kaczmarek, Ł. (2012).Addressing the question of ethical dilemmas in community interpreter training In: S.

Hubscher-Davidson and M. Borodo, eds. Global Trends in Translator and Interpreter Training. London and

New York: Continuum Books. pp. 221–237.

Lam, L.T. (1998). Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Individual Performance. PhD thesis, Texas Tech

University.

Lam, L. T. and Kirby, S. L. (2002). Is emotional intelligence an advantage? An exploration of the impact of

emotional and general intelligence on individual performance. Journal of Social Psychology, 142 (1), pp. 133–

143.

Laripour, N. and Nejad, A.P. (2013). The Relationship between Foreign Language Anxiety and Emotional

Intelligence among Iranian EFL University Students in Bandar Abbas. Journal of Social Issues & Humanities,

Volume 1, Issue 6. [Online] Available at:

http://www.academia.edu/5365961/The_Relationship_between_Foreign_Language_Anxiety_and_Emotional_In

telligence_among_Iranian_EFL_University_Students_in_Bandar_Abbas (Accessed:20 May 2014).

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. R. and Sitarenios, G. (2001). Emotional Intelligence as a standard

Intelligence. [Online] Available at:

http://www.unh.edu/emotional_intelligence/EI%20Assets/Reprints...EI%20Proper/EI2001MSCSAEmotionsArti

cle.pdf (Accessed:27 June 2014).

Mikolajczak, M., Luminet, O., Leroy, C.and Roy, E. (2007). Psychometric Properties of the Trait Emotional

Intelligence Questionnaire: Factor Structure, Reliability, Construct, and Incremental Validity in a French-

Speaking Population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88 (3), pp. 338-353. [Online] Available at:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00223890701333431#.U-8mxfldVyU (Accessed:21 May 2014).

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J. et al (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and

physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion. Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 354–366. [Online]

Available at:

https://www.academia.edu/567400/Increasing_Emotional_Competence_Improves_Psychological_and_Physical

_Well-Being_Social_Relationships_and_Employability (Accessed:15th of August).

Newton, N. (2010). The use of semi-structured interviews in qualitative research:strengths and weaknesses.

Paper submitted in part completion of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of

Bristol. [Online] Available at http://www.academia.edu/1561689/The_use_of_semi-

structured_interviews_in_qualitative_research_strengths_and_weaknesses (Accessed:3 June 2014).

NRPSI (2011) Code of Professional Conduct. [Online] Available at: http://www.nrpsi.org.uk/for-clients-of-

interpreters/code-of-professional-conduct.html (Accessed:10 August 2014).

Petrides, K.V. and Furnham, A. (2000). Gender Differences in Measured and Self-Estimated Trait Emotional

Intelligence. Sex Roles, 42 (5-6) pp. 449-461. [Online] Available at:

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023%2FA%3A1007006523133 (Accessed:12 June 2014).

Petrides, K. V. and Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference

to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15, pp. 425-448. [Online] Available at:

http://www.psychometriclab.com/admins/files/EJP%20(2001)%20-%20T_EI.pdf (Accessed:25 May 2014)/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dissertationdianasingureanu-160627111727/75/Interpreters-and-Emotional-Intelligence-How-do-we-use-it-and-why-does-it-matter-46-2048.jpg)

![47

Petrides, K.V., Furnham, A. and Frederickson, N. (2004). Emotional Intelligence. K.V. Petrides, Adrian Furnham

and Norah Frederickson argue for a trait approach to the misunderstood construct. The Psychologist, 17 (10).

[Online] Available at: http://www.thepsychologist.org.uk/archive/archive_home.cfm/volumeID_17-

editionID_111-ArticleID_758-getfile_getPDF/thepsychologist/1004petr.pdf (Accessed:11 June 2014).

Petrides, K. V., Furnham, A. and Martin, G. N. (2004). Estimates of emotional and psychometric intelligence:

Evidence for gender-based stereotypes. The Journal of Social Psychology,144 (2), pp. 149-162. [Online]

Available at: http://www.psychometriclab.com/admins/files/JSP%20paper%20(unedited).pdf (Accessed:20 June

2014).

Petrides, K. V., Pita, R. and Kokkinaki, F. (2007). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality

factor space. British Journal of Psychology,98 (2), pp.273 -289. [Online] Available at:

http://www.psychometriclab.com/admins/files/bjp%20(2007)%20-%20t_ei.pdf (Accessed:1 June 2014).

Qualter, P., Gardner, K.J. and Whitely, H.E. (2007). Emotional Intelligence: Review of Research and

Educational Implications. Pastoral Care, 25 (1). [Online] Available at:

http://web.b.ebscohost.com.lmu.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=56bea3d4-d51f-43bd-

8024-8a45a8749d57%40sessionmgr110&hid=125 (Accessed:20 May 2014).

Qualter, P., Whiteley, H. E., Hutchinson,J. M. and Pope, D. J., (2007) Supporting the Development of

Emotional Intelligence Competencies to Ease the Transition from Primary to High School. Educational

Psychology in Practice,23 (1), pp. 79–95. [Online] Available at:

http://web.b.ebscohost.com.lmu.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e9b2594c -5674-4329-a99e-

619c9ee9883d%40sessionmgr111&vid=1&hid=125 (Accessed 1 May 2014).

Roy, C., and Metzger, M. (2014). Researching signed language interpreting research through a sociolinguistic

lens.The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research, 6 (1), pp 158-176.

Salovey, P. and Mayer, J. (1990 ). Emotional intelligence. Imagination,Cognition,and Personality,9, pp. 185-

211. Reprinted in: P. Salovey, M. Brackett and J. Mayer, eds. Emotional Intelligence – Key Readings on the

Mayer and Salovey Model. New York: Dude Publishing, pp. 1-27.

Schweda Nicholson, N. (2005). Personality characteristics of interpreter trainees: The Myers -Briggs Type

Indicator (MBTI). The Interpreters' Newsletter 13. pp. 109-142.

Seleskovitch, D. (1978). Interpreting for International Conferences.Washington DC: Pen & Booth.

Singureanu, D., Watson,M., Crenicean, O. and Hojbota, S. (2013). What is the importance of Emotional

Intelligence in Consecutive Interpreting? Presentation as part of the exam for The interpreter’s skills and tools

module at London Metropolitan University.

Thorndike, E.L. (1920). Intelligence and its uses. Harper’s Magazine,140, pp. 227–235.

Uva, M. C. de S., de Timary, P., Cortesia, M., et al (2009). Moderating effect of emotional intelligence on the

role of negative affect in the motivation to drink in alcohol dependent subjects undergoing protracted

withdrawal. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(1), pp.16-21.

Vernon, P. A., Villani, V. C., Schermer, J. A. and Petrides, K. V. (2008). Phenotypic and genetic associations

between the Big Five and trait emotional intelligence. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 11 Number (5), pp.

524–530. [Online] Available at: http://www.psychometriclab.com/admins/files/Twin%20Research%20-

%20Trait%20EI.pdf ( Accessed:17 July 2014).

Zwischenberger, C. and Pöchhacker. F. (2010). Survey on Quality and Role: Conference Interpreters and€

Expectations and Self-perceptions. The AIIC Webzine, 53, [Online] Available at:

http://aiic.net/page/3405/survey-on-quality-and-role-conference-interpreters-expectations-and-self-

perceptions/lang/1(Accessed:20 May 2014).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dissertationdianasingureanu-160627111727/75/Interpreters-and-Emotional-Intelligence-How-do-we-use-it-and-why-does-it-matter-47-2048.jpg)