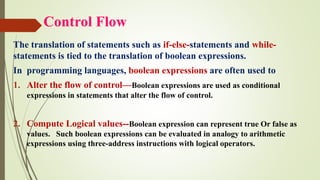

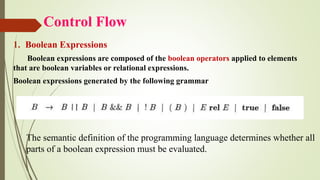

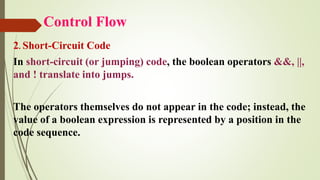

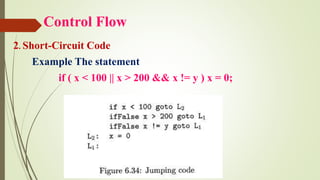

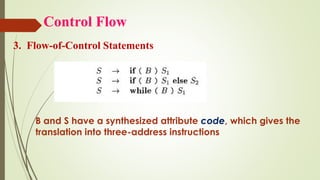

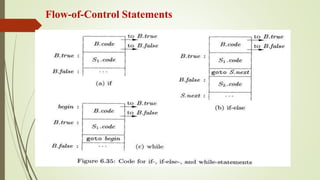

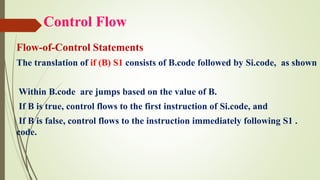

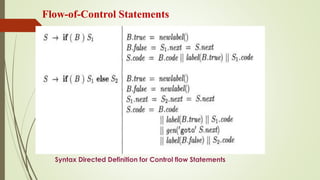

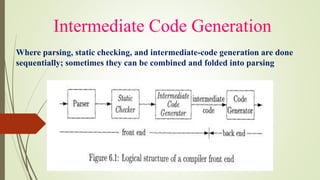

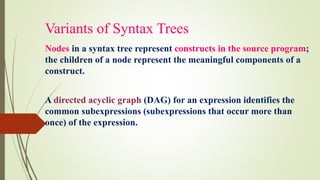

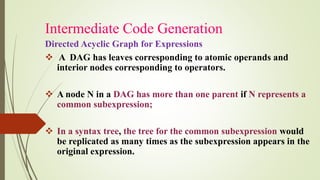

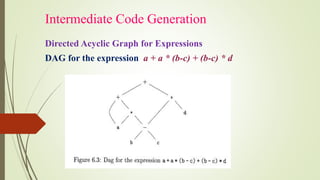

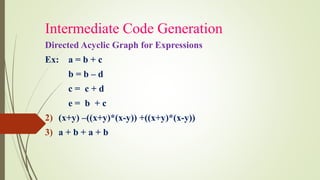

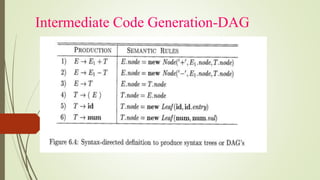

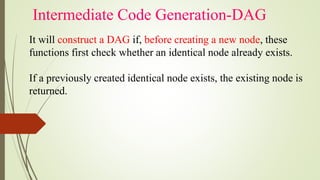

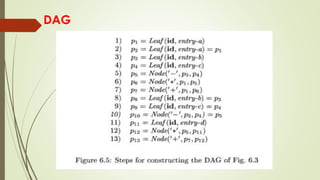

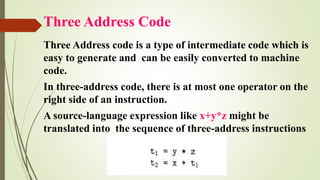

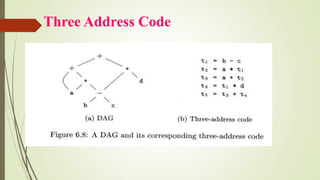

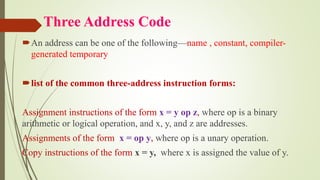

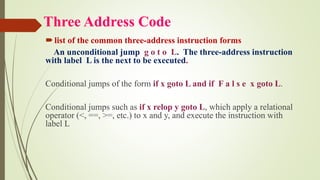

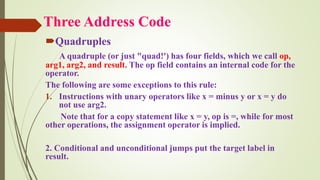

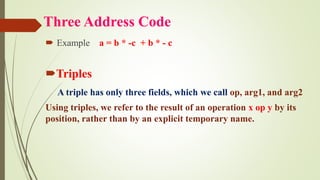

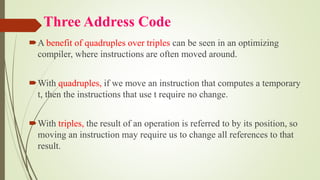

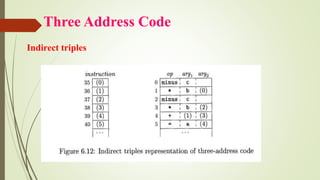

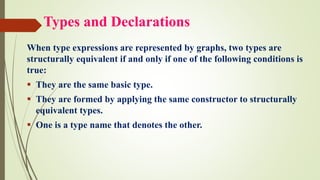

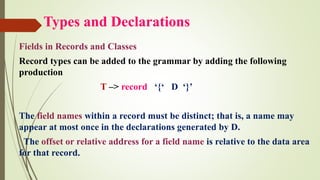

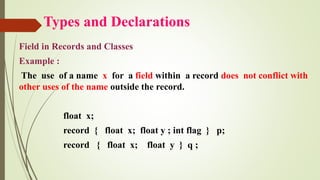

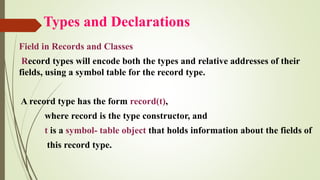

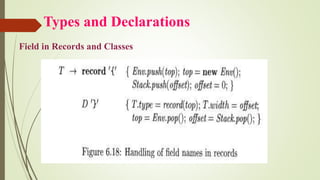

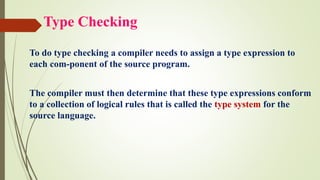

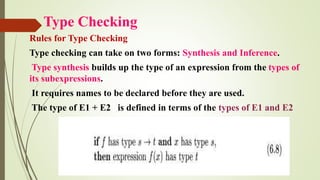

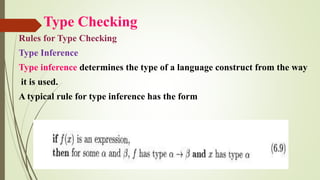

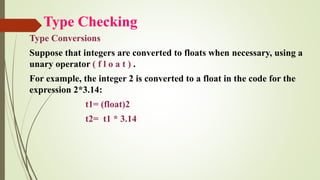

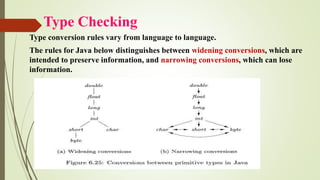

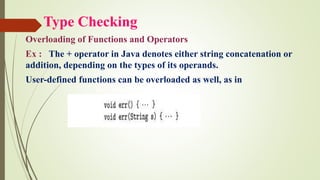

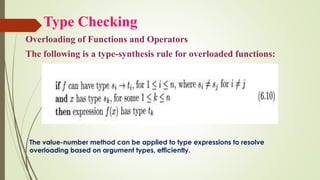

The document details the process of intermediate code generation in compiler design, outlining how source programs are analyzed to create an intermediate representation for target code generation. It discusses various forms of intermediate representations, such as syntax trees, directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), and three-address code, including their uses for tasks like type checking and instruction selection. Additionally, it covers type expressions, type checking, control flow, and how these concepts interact within programming languages.

![Three Address Code

Consider the statement

do i = i + 1 ; while ( a [ i ] < v ) ;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/intcode-cdunit-3-240816071142-b2236011/85/INTERMEDIATE-CODE-GENERTION-CD-UNIT-3-pdf-30-320.jpg)

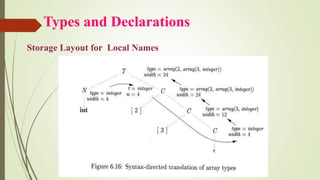

![Types and Declarations

Example :

The array type i n t [2] [3] can be read as

"array of 2 arrays of 3 integers each" and

written as a type expression array(2, array(3, integer))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/intcode-cdunit-3-240816071142-b2236011/85/INTERMEDIATE-CODE-GENERTION-CD-UNIT-3-pdf-39-320.jpg)

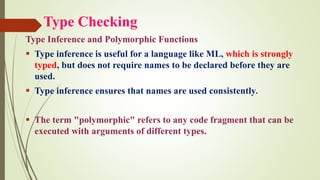

![Type Checking

Type Inference and Polymorphic Functions

The type of length can be described as, "for any type a, length maps a

list of elements of type a to an integer."

length([" sun", "mon", "tue"]) + length([10,9,8, 7])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/intcode-cdunit-3-240816071142-b2236011/85/INTERMEDIATE-CODE-GENERTION-CD-UNIT-3-pdf-65-320.jpg)