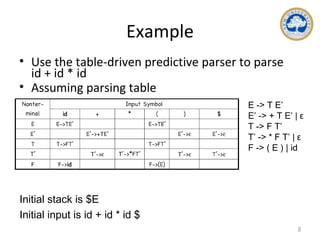

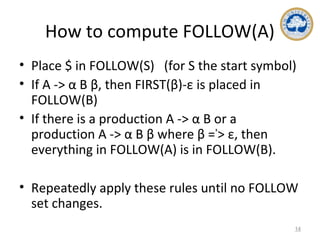

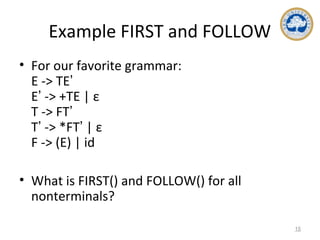

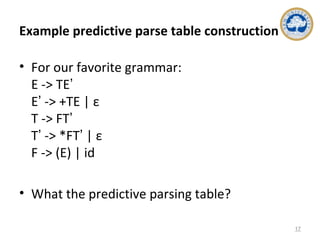

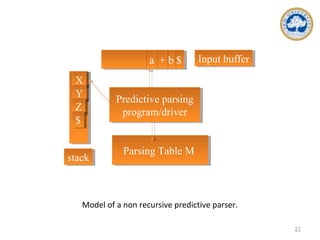

This document discusses top-down parsing and different types of top-down parsers, including recursive descent parsers, predictive parsers, and LL(1) grammars. It explains how to build predictive parsers without recursion by using a parsing table constructed from the FIRST and FOLLOW sets of grammar symbols. The key steps are: 1) computing FIRST and FOLLOW, 2) filling the predictive parsing table based on FIRST/FOLLOW, 3) using the table to parse inputs in a non-recursive manner by maintaining the parser's own stack. An example is provided to illustrate constructing the FIRST/FOLLOW sets and parsing table for a sample grammar.

![The parsing table and parsing program

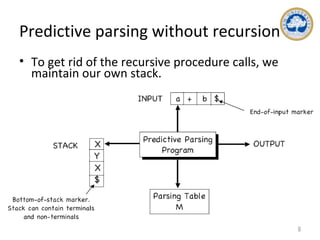

• The table is a 2D array M[A,a] where A is a

nonterminal symbol and a is a terminal or $.

• At each step, the parser considers the top-of-

stack symbol X and input symbol a:

If both are $, accept

If they are the same (nonterminals), pop X, advance

input

If X is a nonterminal, consult M[X,a].

– If M[X,a] is “ERROR” call an error recovery routine.

Otherwise, if M[X,a] is a production of the

grammar X -> UVW, replace X on the stack with WVU

(U on top)

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/top-downparsing-140726023737-phpapp01/85/Top-down-parsing-7-320.jpg)

![Parse table construction with

FIRST/FOLLOW

• Basic idea: if A -> α and a is in FIRST(α), then we expand A to α any time

the current input is a and the top of stack is A.

• Algorithm:

• For each production A -> α in G, do:

• For each terminal a in FIRST(α) add A -> α to M[A,a]

• If ε FIRST(α), for each terminal b in FOLLOW(A), do:∈

• add A -> α to M[A,b]

• If ε FIRST(α) and $ is in FOLLOW(A), add A -> α to M[A,$]∈

• Make each undefined entry in M[ ] an ERROR

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/top-downparsing-140726023737-phpapp01/85/Top-down-parsing-16-320.jpg)

![LL(1) grammars

• The predictive parser algorithm can be applied to

ANY grammar.

• But sometimes, M[ ] might have multiply defined

entries.

• Example: for if-else statements and left factoring:

stmt -> if ( expr ) stmt optelse

optelse -> else stmt | ε

• When we have “optelse” on the stack and “else”

in the input, we have a choice of how to expand

optelse (“else” is in FOLLOW(optelse) so either

rule is possible)

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/top-downparsing-140726023737-phpapp01/85/Top-down-parsing-18-320.jpg)

![LL(1) grammars

• If the predictive parsing construction for G leads to a

parse table M[ ] WITHOUT multiply defined entries,

we say “G is LL(1)”

19

1 symbol of lookahead

Leftmost derivation

Left-to-right scan of the input](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/top-downparsing-140726023737-phpapp01/85/Top-down-parsing-19-320.jpg)

![Nonrecursive Predictive Parsing

• 1. If X = a = $, the parser halts and announces successful completion of parsing.

• 2. If X = a ≠ $, the parser pops X off the stack and advances the input pointer to the next

input symbol.

• 3. If X is a nonterminal, the program consults entry M[X, a] of the parsing table M. This

entry will be either an X-production of the grammar or an error entry. If, for example, M[X, a]

= {X → UVW}, the parser replaces X on top of the stack by WVU (with U on top). As output,

we shall assume that the parser just prints the production used; any other code could be

executed here. If M[X, a] = error, the parser calls an error recovery routine.

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/top-downparsing-140726023737-phpapp01/85/Top-down-parsing-23-320.jpg)