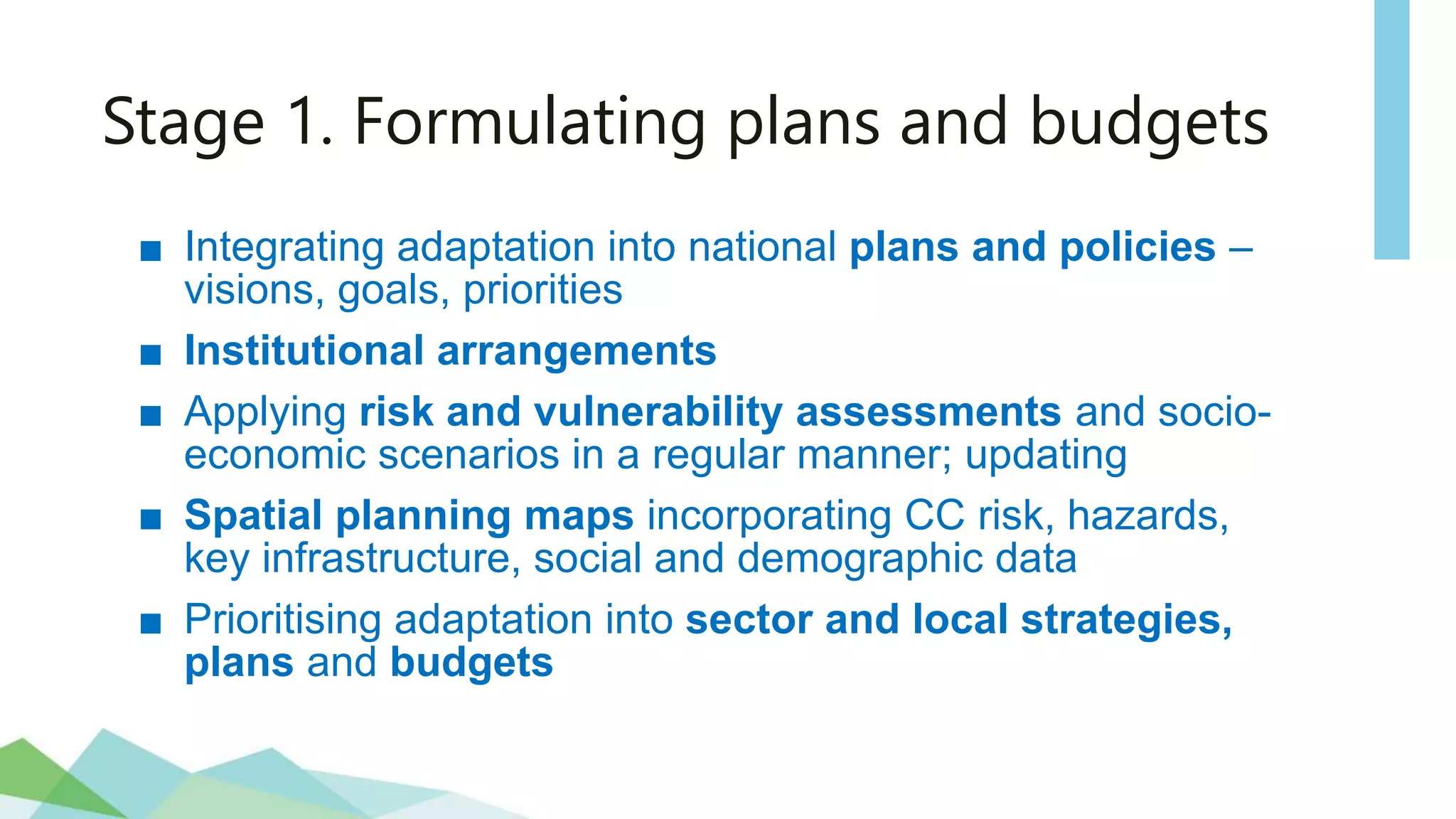

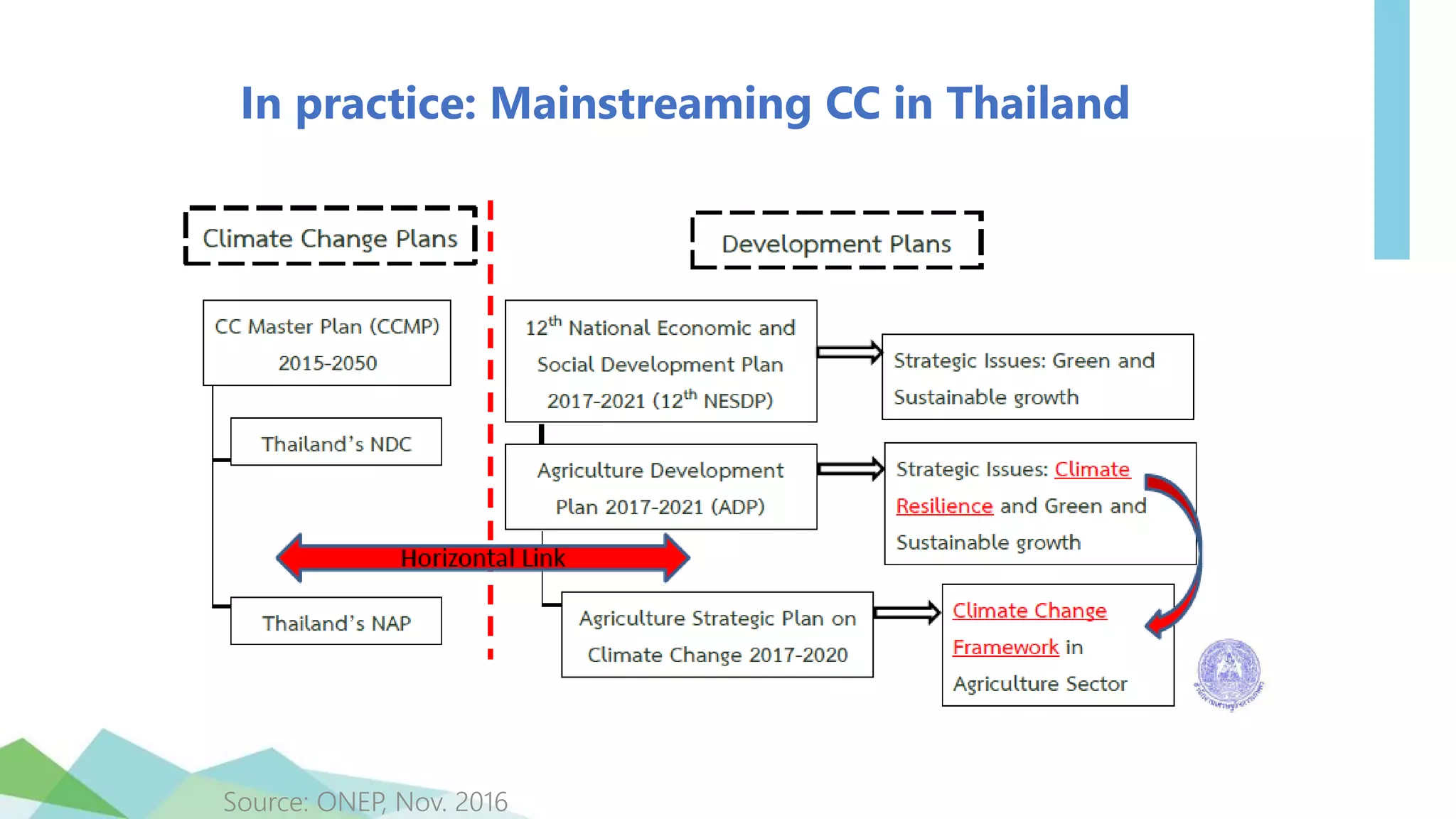

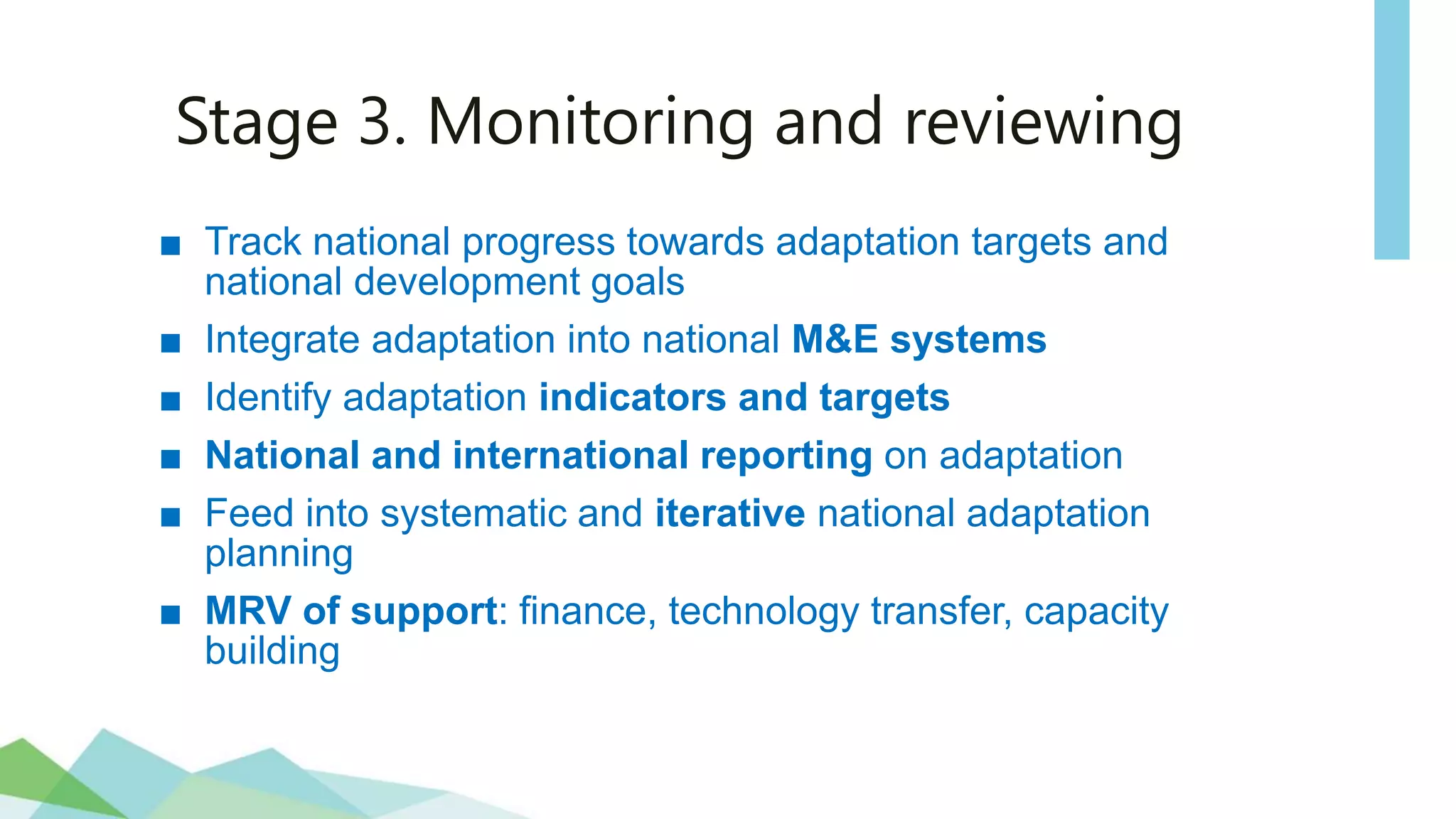

This document discusses integrating climate change adaptation into national planning and budgeting processes. It begins by outlining the national adaptation plan (NAP) process established by the UNFCCC to help countries reduce climate change vulnerability and integrate adaptation into relevant policies and activities. The document then discusses opportunities to align NAPs with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It provides examples of how countries have integrated adaptation into different stages of the planning process, from formulation to implementation to monitoring and review. The document also discusses integrating adaptation into budgeting, including through climate budget tagging and financing frameworks. It emphasizes the importance of institutional arrangements and capacity building to support integrated adaptation planning and budgeting.