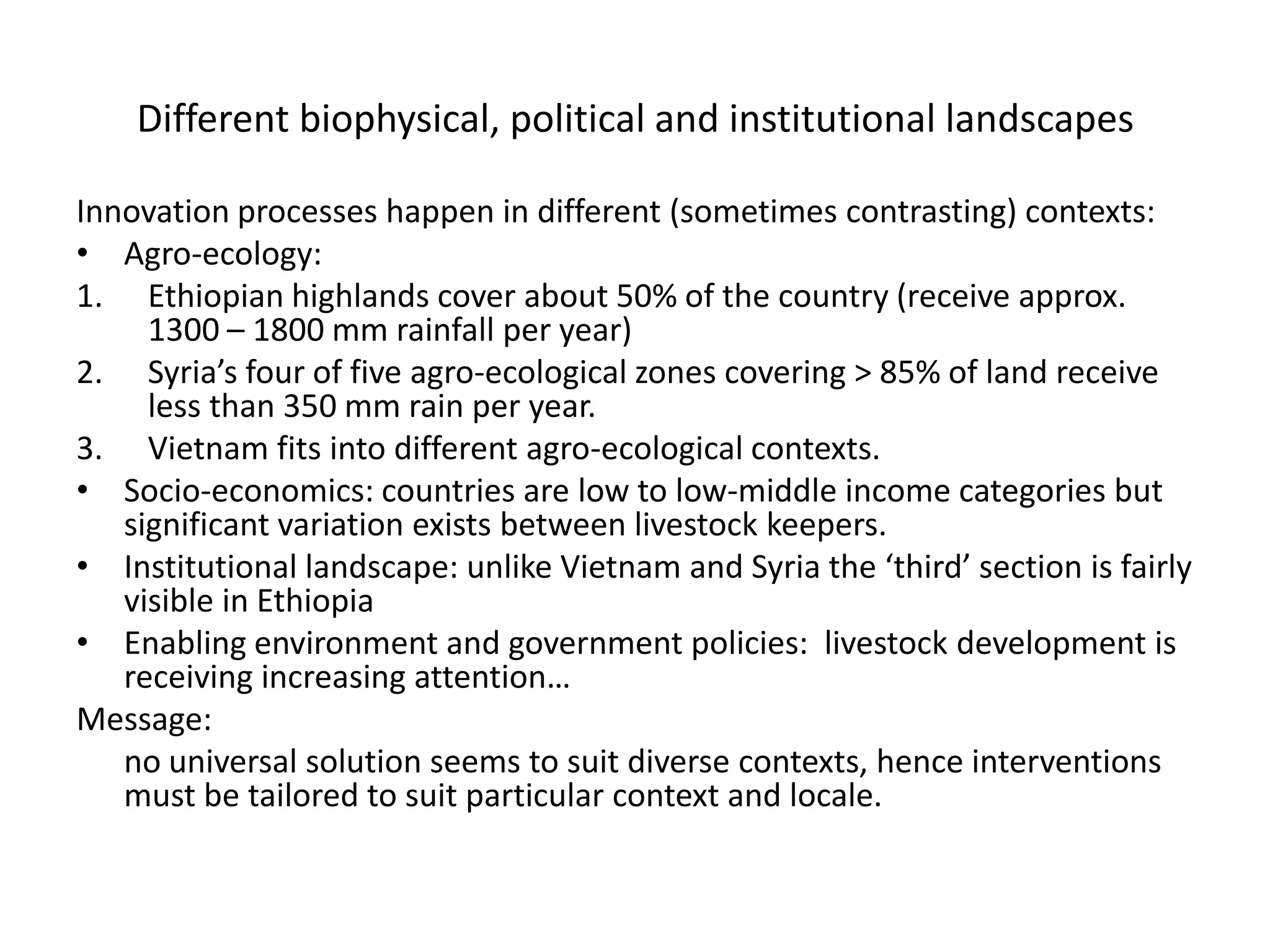

The document discusses innovation processes and outcomes related to fodder and feed in livestock systems across Ethiopia, Syria, and Vietnam, highlighting significant regional variations in scarcity and productive capacity. It emphasizes the importance of context-specific interventions and stakeholder involvement in developing effective solutions for fodder supply issues. Key challenges include access to credit and adaptability of solutions to local needs, with successful interventions noted for their market integration and community acceptance.

![Successes and more challenges …Why Dr Khan thinks the Ea Kar experiment is a rewarding and sustainable endeavour: … I see sustainability of an intervention in terms of meeting local needs and fitting to local context. … it is also important that an intervention is accepted by a local government to get political support and receive funds for development. The fodder species we have introduced meet those criteria and they have been increasingly taken up by the local network and farmers (Dr Khan, NTU). In El Bab (Syria) fodder technology adoption seems moving fast: … now our own farmers are producing and distributing fodder seeds to other farmers. Last year a farmer [in El Bab] planted barley on one ha, this year [2009] on 10 ha and sold some of the seed to three farmers in the village. The technology is expanding like ‘wild fire’ (Farmer/School Principal, El Bab).Success is not everywhere and there still are more challenges … …yes we earn more money now from fattening than two or three years ago … but still raising capital … to buy an animal is a problem. We don’t get bank credit because of tight collateral conditions … (Mrs. Phan Thi Nguyet, Head of Farmer Group, Village 8).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fapsymposiumayele-101118094314-phpapp01/75/Innovation-processes-and-outcomes-in-different-national-contexts-preliminary-findings-of-FAP-meta-analysis-8-2048.jpg)