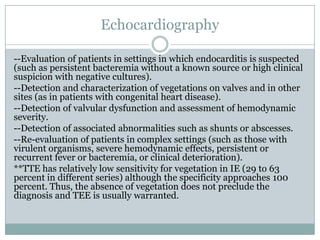

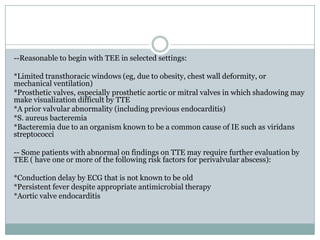

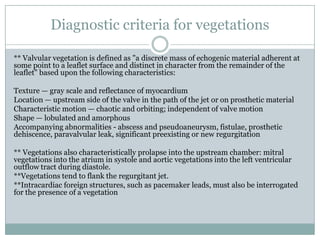

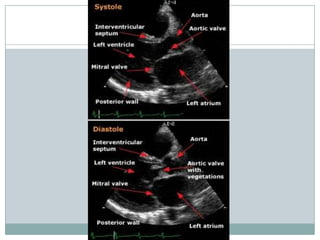

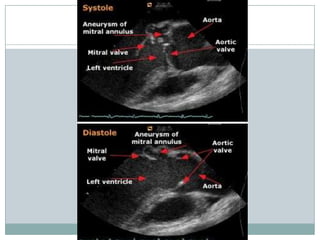

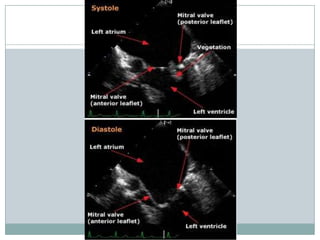

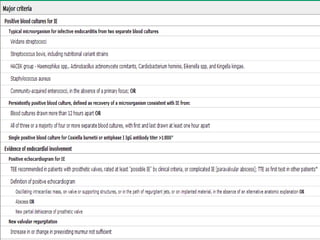

Staphylococci and streptococci account for the majority of infective endocarditis cases. The most common organism causing subacute native valve endocarditis is Streptococcus viridans, while Staphylococcus aureus is most common in intravenous drug users. Blood cultures, echocardiography, and physical exam are important for diagnosis, with echocardiography able to identify valvular vegetations. Transesophageal echocardiography has higher sensitivity than transthoracic echocardiography for detecting vegetations.