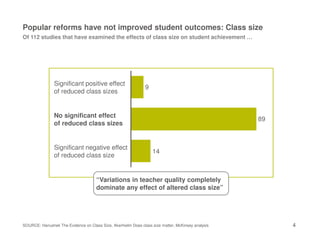

This document provides an overview of improving education systems and outcomes in Turkey based on McKinsey & Company's research and experience working with education systems around the world. It identifies four key themes for improving Turkey's education system: 1) cultivating great teaching and school leadership at a large scale, 2) creating student pathways to success and employment, 3) equipping Turkish students with English proficiency, and 4) improving the role of regional/local education authorities. The document also discusses lessons learned from education systems that have improved, such as the importance of process interventions like collaborative teaching practices.

![12

Our research finds that a unique ‘intervention cluster’ exists for each

improvement journey

SOURCE: McKinsey & Company

Fair to good Good to greatPoor to fair

Great to

excellent

Journey

Shaping the

professional

Improving

through peers

and innovation

Achieving

the basics

of literacy and

numeracy

Getting the

foundations

in place

Intervention

cluster

theme

Common

across all

journeys

Six interventions

1] Revising curriculum and standards

2] Reviewing remunerations

structure

3] Building technical skills

4] Assessing student

5] Utilizing student learning data

6] Revising policy or education

laws](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110906improvingeducationinturkeyfinalprint-150314112017-conversion-gate01/85/Improving-education-in-turkey-final-print-13-320.jpg)

![49

A surprising number of teachers across OECD systems do not receive

regular appraisal or feedback

31

23

36

More than once

per year

Once per year

Never or Once

every two or

more years

49

13

38

22

13

65

SOURCE: Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) first results, OECD, 2009,

1 TALIS Survey was conducted in 23 OECD and partner countries: [OECD] – Australia, Austria, Flemish Belgium, Denmark, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland,

Italy, Korea, Mexico, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Spain, and Turkey; [Partner countries] – Brazil, Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania,

Malaysia, Malta, Slovenia

From principals

From peers or senior

teachers

From external

individual or body

5

Teacher reported frequency of appraisal and/or feedback

Percent (TALIS average1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110906improvingeducationinturkeyfinalprint-150314112017-conversion-gate01/85/Improving-education-in-turkey-final-print-50-320.jpg)

![50

However, appraisal and feedback usually increases

teacher job satisfaction

Impact of appraisal and feedback on teachers’ job satisfaction

Percentage of teachers who reported the following change to job satisfaction

following the appraisal and/or feedback they received in their school, TALIS1

7

41

52

Decreased

Did not change

Increased

SOURCE: Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) first results, OECD, 2009,

1 TALIS Survey was conducted in 23 OECD and partner countries: [OECD] – Australia, Austria, Flemish Belgium, Denmark, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland,

Italy, Korea, Mexico, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Spain, and Turkey; [Partner countries] – Brazil, Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania,

Malaysia, Malta, Slovenia

5

Appraisal and feedback also had a positive

impact on teachers performance, with ~40%

of teachers reporting that it made significant

differences in their teaching](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110906improvingeducationinturkeyfinalprint-150314112017-conversion-gate01/85/Improving-education-in-turkey-final-print-51-320.jpg)

![72SOURCE: McKinsey & Company interventions database

Poor to fair Fair to good Good to great

Intervention

cluster1

▪ Raising calibre of

entering teachers and

principals

– Recruiting programs

– Pre-service training

– Certification

requirements

▪ Raising calibre of

existing teachers and

principals

– In-service training

programs

– Coaching on practice

– Career tracks

– Teacher and

community forums

▪ School-based decision-

making

– Self-evaluation

– Independent and

specialized schools

▪ Cultivating peer-led learning

for teachers and principals

– Collaborative practice

– Decentralizing pedagogical

rights to schools & teachers

– Rotation and secondment

programs

▪ Creating additional support

mechanisms for professionals

– Release professionals from

admin burden by providing

additional administrative staff

▪ System-sponsored

experimentation/innovation

across schools

– Providing additional funding

for innovation

– Sharing innovation from front-

line to all schools

▪ Providing motivation and

scaffolding for low skill

teachers

– Scripted teaching materials

– Coaching on curriculum

– Instructional time on task

– School visits by center

– Incentives for high

performance

▪ Getting all schools to a

minimum quality level

– Outcome targets

– Additional support for low

performing schools

– School infrastructure

improvement

– Provision of textbooks

▪ Getting students in seats

– Expand school seats

– Fulfil students’ basic needs

to raise attendance

▪ Data and accountability

foundation

– Transparency to schools

and/or public on school

performance

– School inspections and

inspections institutions

▪ Financial and organizational

foundation

– Optimization of school and

teacher volumes

– Decentralizing financial and

administrative rights

– Increasing funding

– Funding allocation model

– Organizational redesign

▪ Pedagogical foundation

– School model/ streaming

– Language of instruction

Shaping the professional Improving through peers

and innovation

Achieving the basics of

literacy and numeracy

Getting the foundations in

place

Theme

Great to excellent

Improvement

journey

Common

across all

journeys

Six interventions: [1] Revising curriculum and standards; [2] Reviewing reward and remunerations structure; [3] Building technical skills

of teachers and principals, often through group or cascaded training; [4] Assessing student learning; [5] Utilizing student data to guide

delivery, and [ 6] Establishing policy documents and education laws

1 Total number of interventions in each phase: poor to fair, n=103, fair to good, n=226; good to great, n=150; great to excellent, n=94

A unique ‘intervention cluster’ exists for each improvement journey,

with six interventions common across all journeys](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110906improvingeducationinturkeyfinalprint-150314112017-conversion-gate01/85/Improving-education-in-turkey-final-print-73-320.jpg)

![74

Turkey’s student performance on PISA reflects a

wide spread of proficiency

Below Level 1 18%

Level 1 25%

Level 2 25%

Level 3 17%

Level 4 10%

Level 5 4%

Level 6 1%

Level 6: Can conceptualise,

generalise, and utilise

information [in] complex

problem situtations…

advanced reasoning…can

formulate and communicate

actions and reflections

High

Low

Level 3: Executes clearly

defined procedures [and]

develop short

communications…

Level 1: Can answer

questions involving familiar

contexts…carry out routine

problems…perform actions

that are obvious

Turkish students’ performance by proficiency level on 2009 PISA Mathematics

SOURCE: OECD PISA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20110906improvingeducationinturkeyfinalprint-150314112017-conversion-gate01/85/Improving-education-in-turkey-final-print-75-320.jpg)