This document provides a comprehensive guide to rights and responsibilities under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004). It covers topics such as pre-referral services, evaluations, eligibility determinations, individualized education programs, transition services, discipline procedures, and dispute resolution options. The guide aims to help parents understand how IDEA works and become effective advocates for their children.

![For Chapter 7: Individualized Education Program (IEP) (pages 36-44)

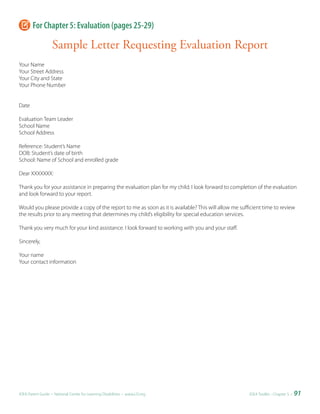

Sample Letter Regarding IEP Team Member Excusal

Your Name

Your Street Address

Your City and State

Your Phone Number

Date

Name of IEP Team Leader or School Principal

School Name

School Address

Reference: Student’s Name

DOB: Student’s date of birth

School: Name of School and enrolled grade

Dear XXXXXXX:

I look forward to our meeting to formulate the Individualized Education Program for [student’s name].

I am aware that IDEA 2004 now allows for certain IEP team members to be excused from attending this meeting upon my

written agreement. While I understand that bringing together the full IEP team can be difficult, I consider the attendance

of all required IEP team members critical to the development of an appropriate IEP for my child. Therefore, I will not excuse

any member from attending.

Thank you very much for your continuing assistance. I look forward to working with you and your staff.

Sincerely,

Your name

Your contact information

IDEA Parent Guide • National Center for Learning Disabilities • www.LD.org IDEA ToolKit - Chapter 7 • 93](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/idea2004parentguide-100526092123-phpapp01/85/IDEA-2004-Parent-Guide-93-320.jpg)