The document discusses the legal obligations of schools to provide appropriate educational services to students with disabilities, particularly focusing on a student named Destini who has a reading disability. It emphasizes that under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), schools must offer free appropriate public education (FAPE) and outlines the importance of parental rights and involvement in the educational process. It also addresses the necessity of informed consent for evaluations and services, as well as the implications of procedural errors that may affect parental participation in developing Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

![ents clarified that the term related services does not include sur

gically implanted medical devices or their replacements.4 More

over, the regulations specify that optimization of the functionin

g, maintenance, or replacement of these devices is beyond the s

cope of school board responsibilities.5 This does not mean that

school personnel lack all responsibility for monitoring devices o

r making sure that they function properly.6 While these provisio

ns were included to address board responsibilities regarding coc

hlear implants, they apply to other surgically implanted devices

as well.7

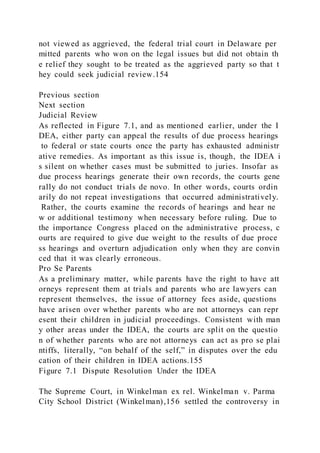

In Irving Independent School District v. Tatro,8 the Supreme Co

urt placed two important limitations on the obligations of school

boards to provide related services. First, the Court insisted that

“to be entitled to related services, a child must be [disabled] so

as to require special education.”9 The Court pointed out that ab

sent a disability requiring special education, “the need for what

otherwise might qualify as a related service does not create an o

bligation under the Act.”10 Second, the Court noted that only se

rvices necessary to aid children with disabilities in benefitting f

rom special education must be provided, regardless of how easil

y such services could be furnished. Thus, students who receive f

ree appropriate public educations (FAPEs) from their special ed

ucation without related services are not entitled to receive such

services. Even though the IDEA does not require school boards

to provide related services to students who are not receiving spe

cial education, as is explained in more detail in Chapter 9, Secti

on 504 may require boards to furnish such services as reasonabl

e accommodations to students with disabilities that may not nec

essarily entitle them to special education.

Supportive services may be deemed related services if they assis

t students with disabilities to benefit from special education. Re

lated services may be provided by persons of differing professio

nal backgrounds with a variety of occupational titles.

The IDEA’s regulations define each of the identified related ser

vices in detail.11 To the extent that these definitions are not exh

austive, any services, other than those that are specifically exem](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conflictingviews-220921182438-096fe28a/85/CONFLICTING-VIEWS-80-320.jpg)

![the EBSCOhost database in the Ashford University Library. The

purpose of this article is to identify factors contributing to

parent-school conflict in special education. The findings

indicate eight common themes that cause conflict and

suggestions for ways to mitigate these disagreements. This

article is referenced in the Week Five discussion, “Conflicting

Views.”

Website

Partners for Student Success. (2014, January 19). Procedural

safeguards for children and parents (Links to an external site.).

Retrieved from

https://www.ssdmo.org/public_notices/safeguards.html

· This website explains the procedural safeguard in parent-

friendly terms. It is referenced in the Week Five assignment,

“Procedural Safeguards.”

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)

Privacy Policy does not exist. Recommended Resources

Article

New Jersey Department of Education. (2012). Parental rights in

special education (Links to an external site.). Retrieved from

http://www.state.nj.us/education/specialed/for m/prise/prise.pdf

· The New Jersey Department of Education provides this

handbook to parents that helps clarify the Procedural

Safeguards in parent-friendly terms. It is a required document

for the Week Five assignment, “Procedural Safeguards.”

Accessibility Statement (Links to an external site.)Privacy

Policy (Links to an external site.)

Multimedia

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Building the legacy of

IDEA: 2004 (Links to an external site.) [Video file]. Retrieved

from

http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/%2Croot%2Cdynamic%2CVid

eoClips%2C7%2C](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conflictingviews-220921182438-096fe28a/85/CONFLICTING-VIEWS-154-320.jpg)

![terms so that you can demonstrate your ability to identify how

they protect the rights of children with disabilities.

There are specific guidelines for the written portion of this

assignment as well as the content. In order to maximize your

score, it is essentially that you follow these instructions closely.

Make sure to use the Grading Rubric as a self-checklist before

submitting the final copy of your assignment to confirm you

have met or exceeded each required expectation. The highest

level of achievement on the rubric is “distinguished”, which is

only earned through exceeding posted expectations at the

proficiency level. Please remember you are in a masters-level

program. Therefore, your writing, research, and content are held

to graduate-level expectations.

ePortfolio

Save this written assignment in your electronic portfolio

(ePortfolio). As you recall, your ePortfolio serves as a

collection of evidence to support the development and mastery

of competencies as you progress through this program and you

will re-visit it in ESE 699, your MASE program capstone

course.

References

Conflict Resolution (Links to an external site.) [Video file].

(n.d.). Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KY5TWVz5ZDU

Factors Contributing to Parent-School Conflict in Special

Education (Links to an external site.). (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://www.advocacyinstitute.org/advocacyinaction/Parent_Scho

ol_Conflict.shtml

Wellner, L. (2012). Building Parent Trust in the Special

Education Setting (Links to an external site.).Leadership, 16-19.

Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ EJ971412.pdf

Zirkel, P.A., & McGuire, B. L. (2010).A roadmap to legal

dispute resolution for students with disabilities.Journal of

Special Education Leadership, 23, 100-112.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conflictingviews-220921182438-096fe28a/85/CONFLICTING-VIEWS-160-320.jpg)