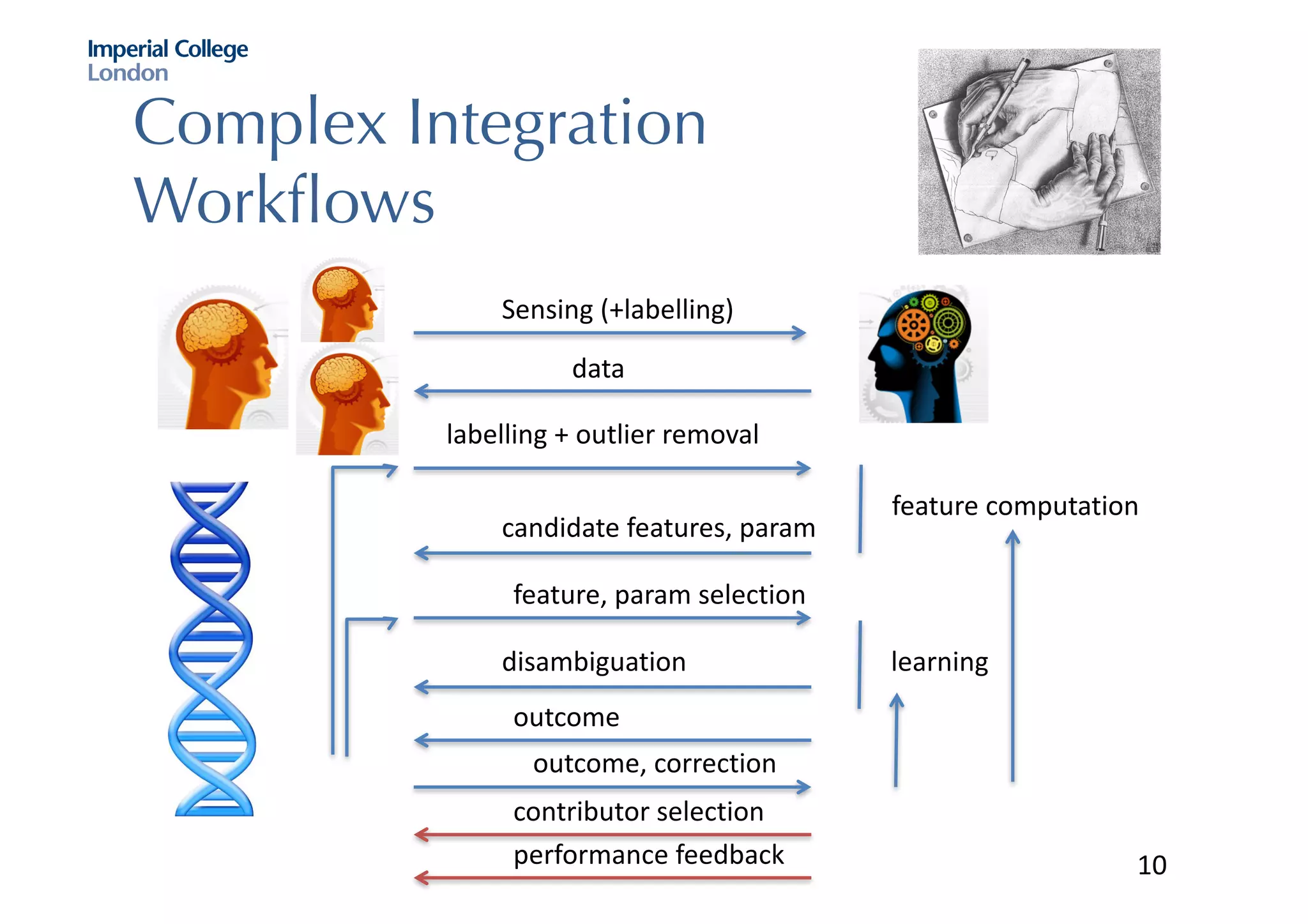

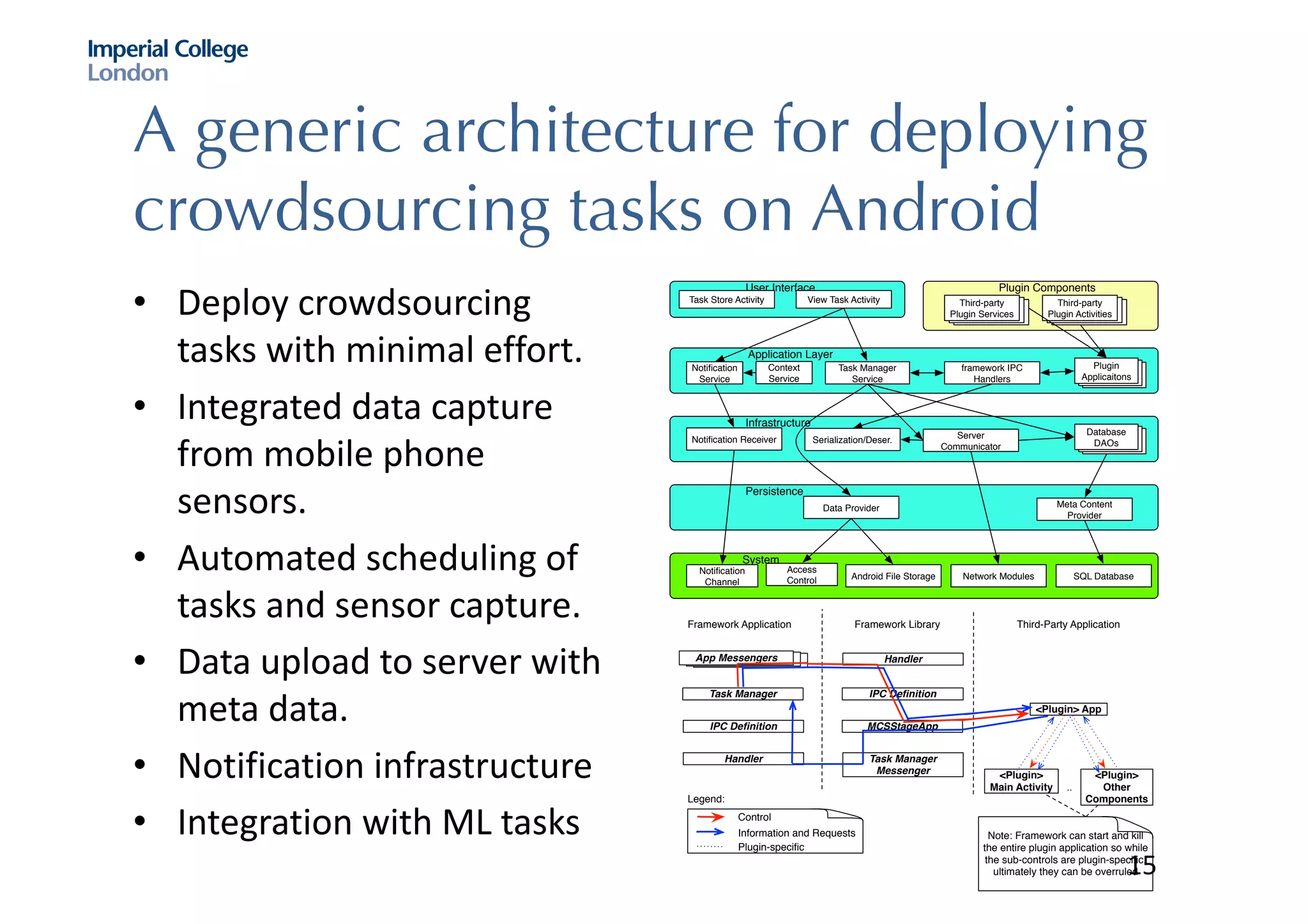

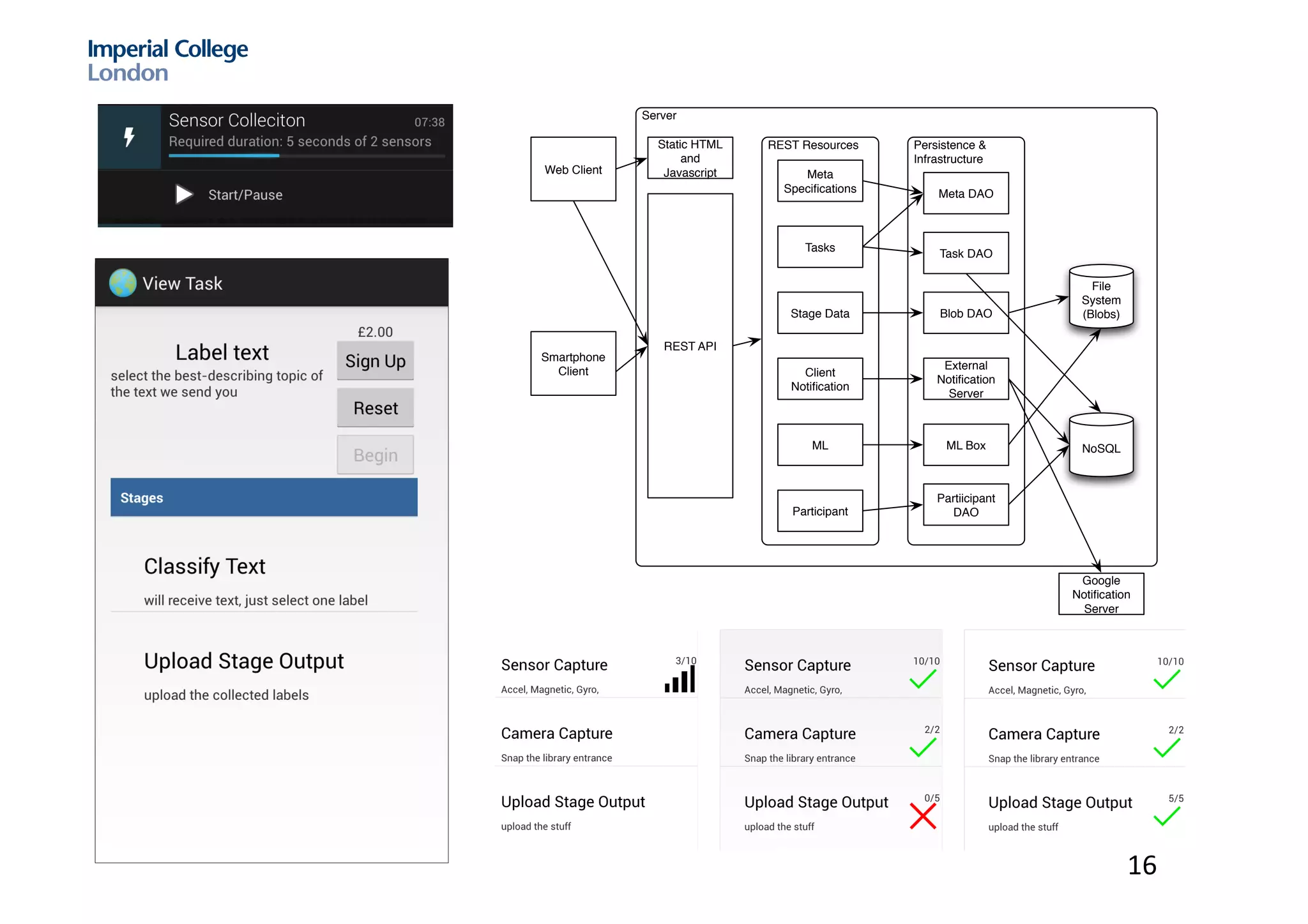

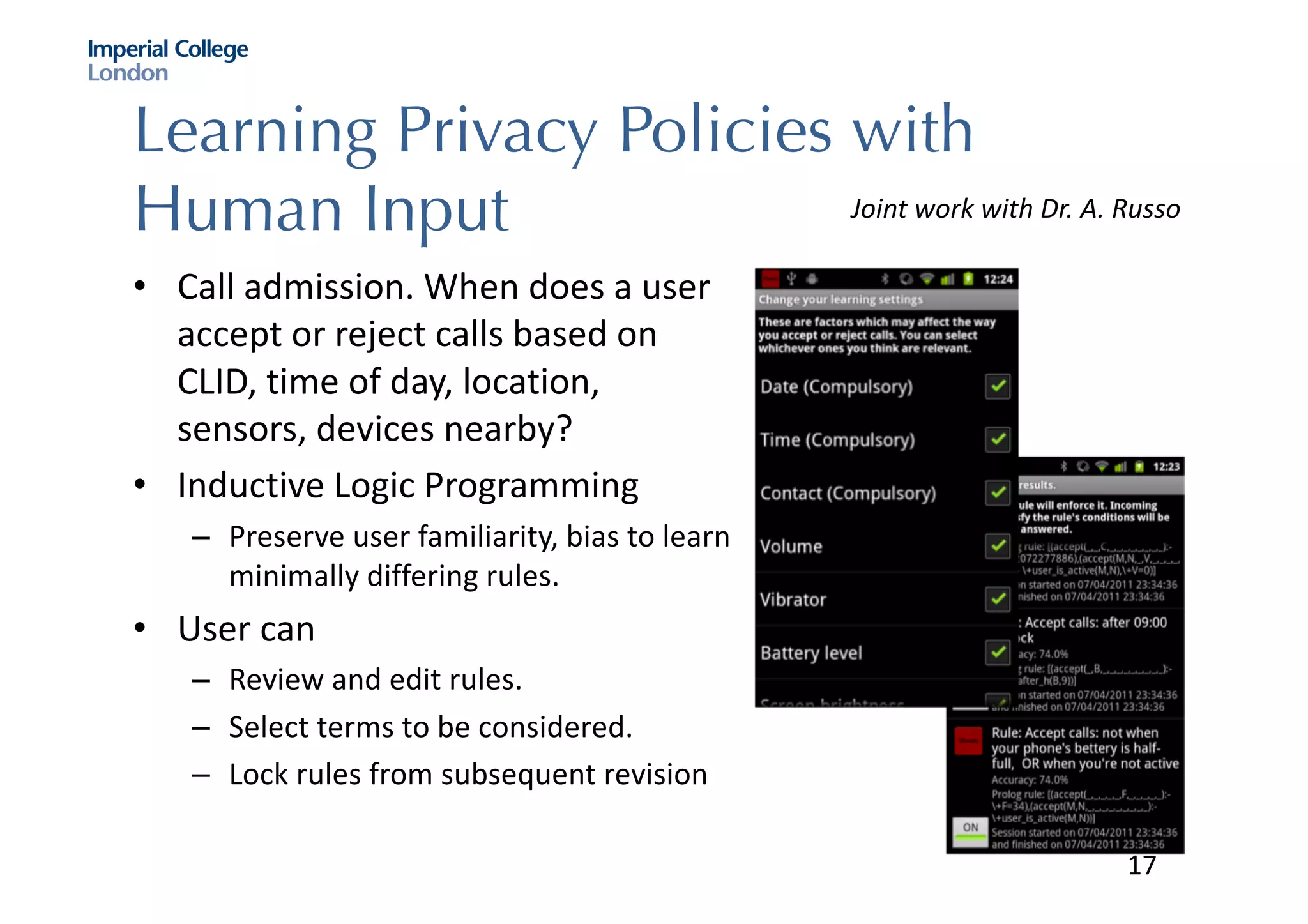

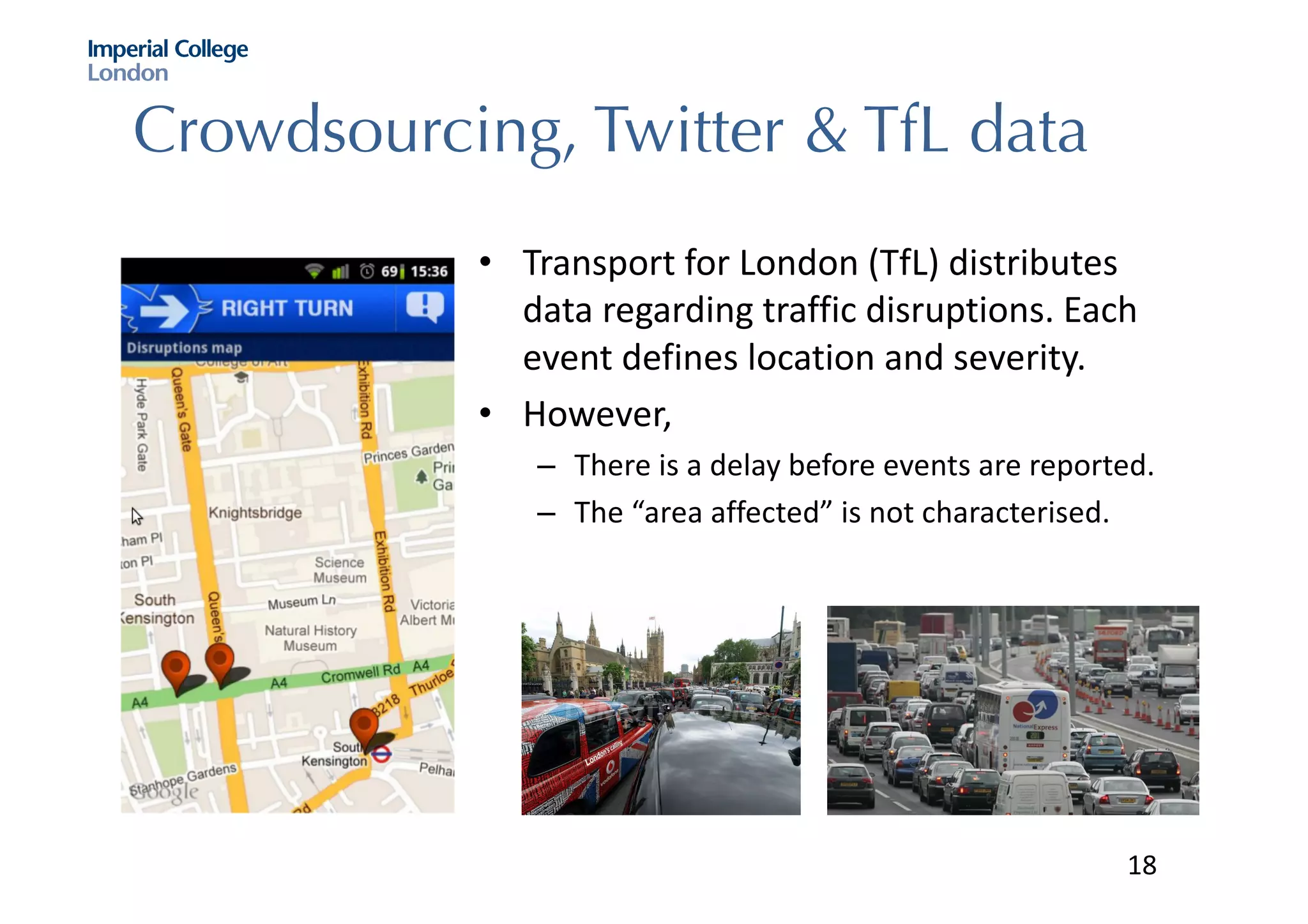

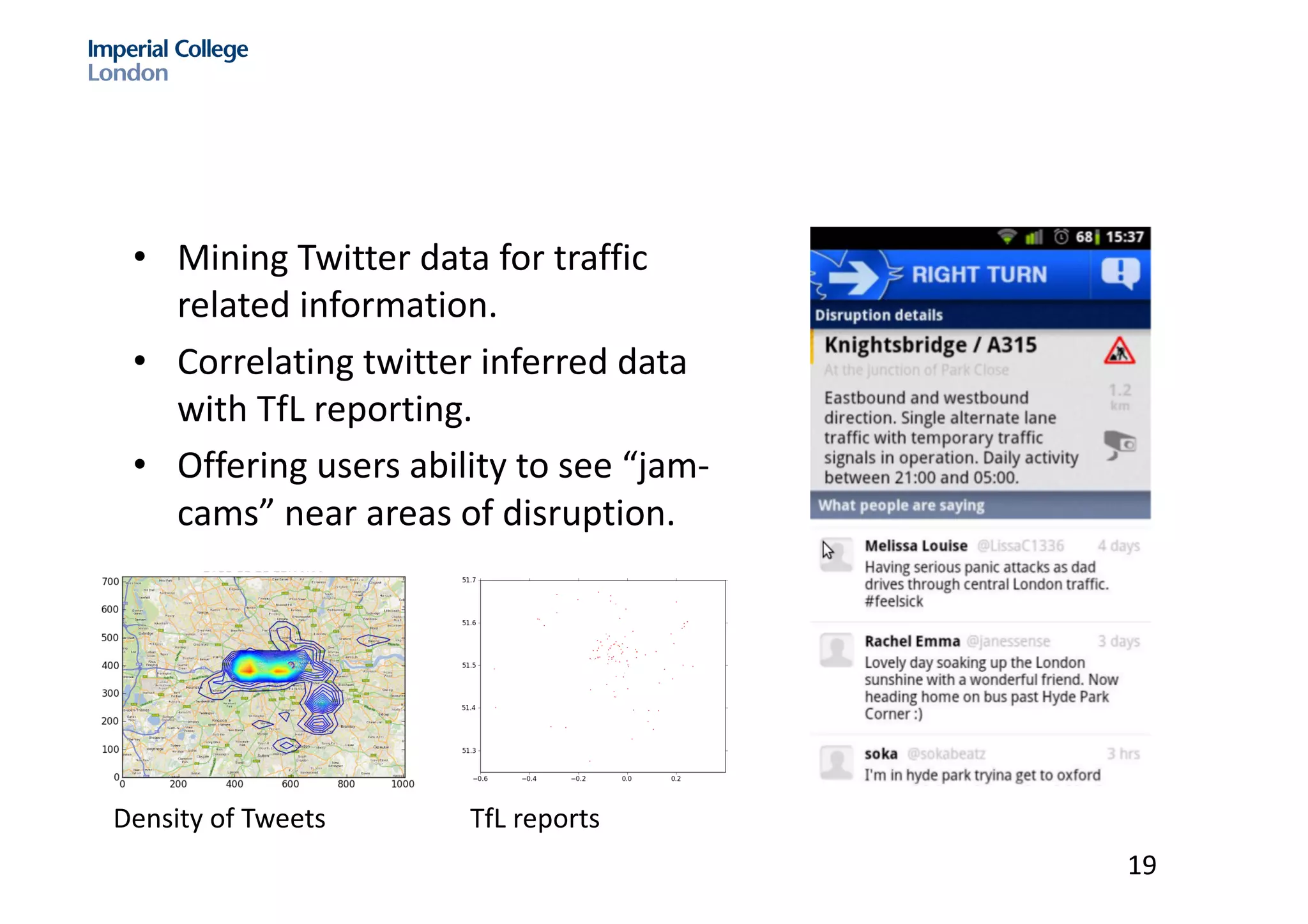

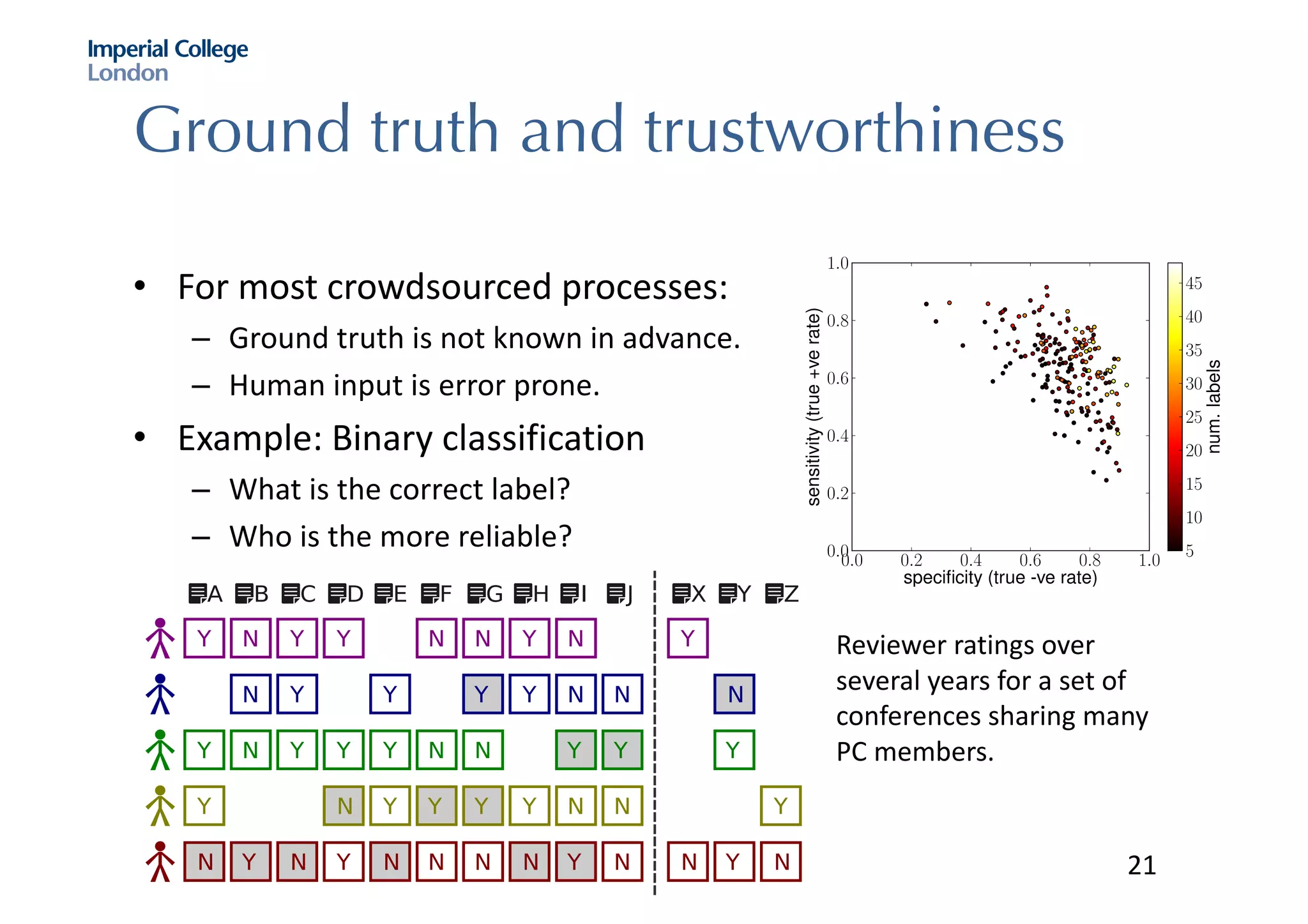

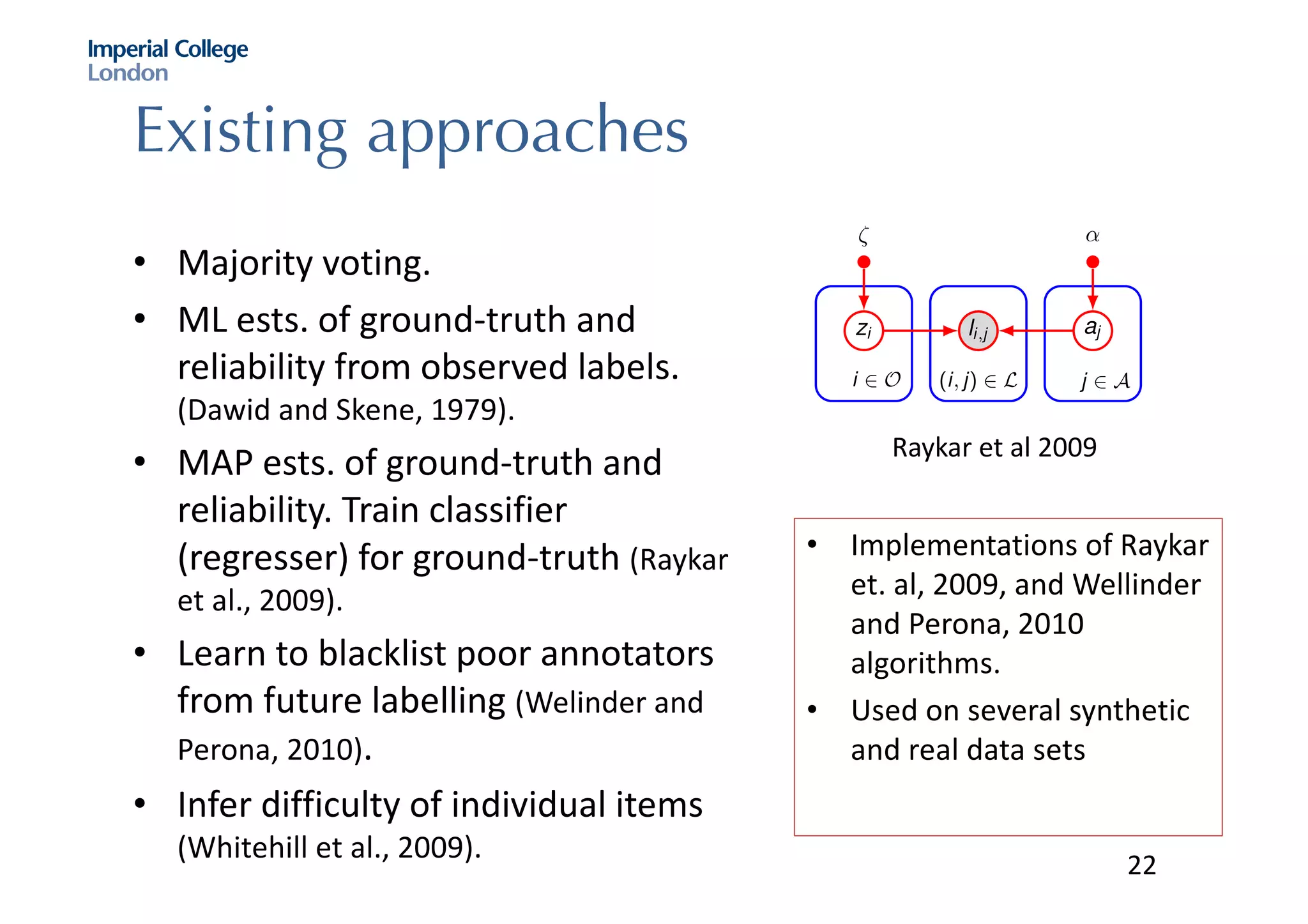

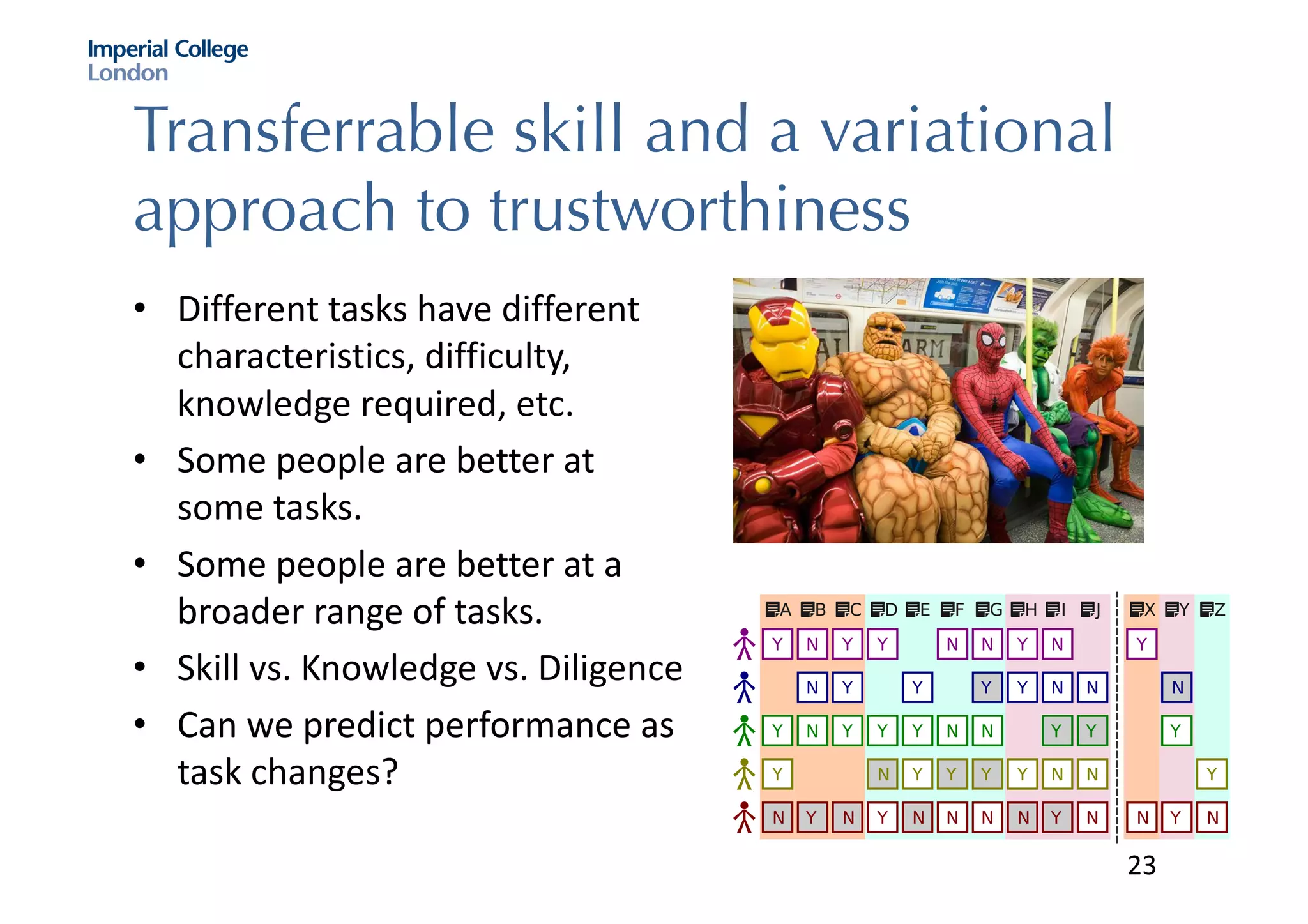

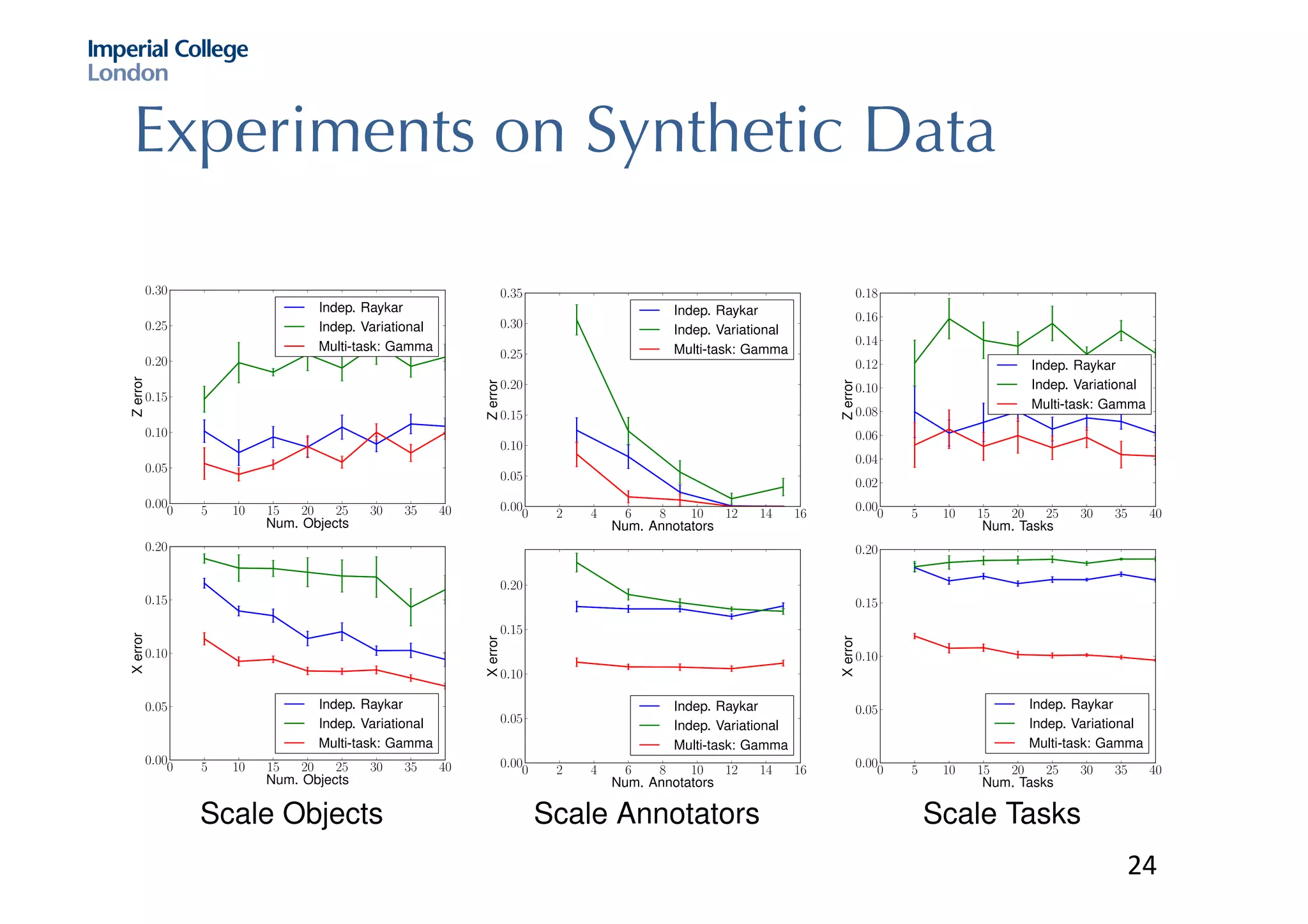

The document discusses hybrid machine learning and crowdsourcing approaches for various tasks. It proposes combining machine learning algorithms with human input to contextualize data, identify patterns, process difficult data, and improve algorithms. Example application areas mentioned include transportation (predicting congestion), shopping/advertising (understanding consumer behavior), healthcare (monitoring epidemics), and document translation. It also addresses challenges like privacy, cost, and ensuring high quality contributions from humans. Methods developed so far include crowdsourcing mobile app architectures, learning privacy policies with human guidance, combining Twitter data with transportation agency reports, and algorithms for estimating ground truth and contributor trustworthiness.