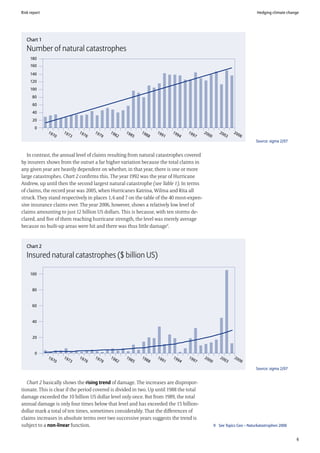

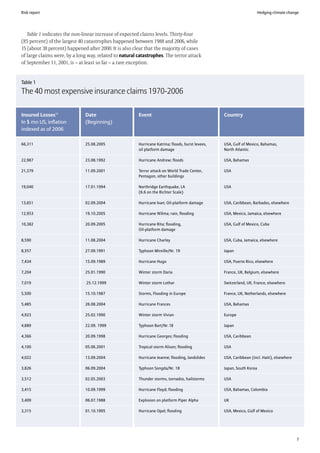

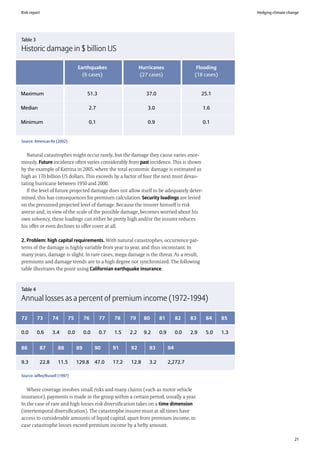

The risk report on hedging climate change by Allianz discusses the rising trend of natural catastrophes linked to climate change and the challenges facing insurers in managing these risks. It highlights the need for innovative solutions such as catastrophe bonds and public-private partnerships to improve insurability amidst significant under-insurance. The report emphasizes that despite the challenges, there are opportunities for growth in emerging markets focused on energy efficiency and sustainability.