This two-volume handbook provides guidance on implementing Total Quality Management (TQM) and Quality Control Circles (QCC). Volume I is intended for managers and explains the concepts and benefits of TQM and QCC. It also provides guidance on installing and implementing TQM and QCC programs in organizations. Volume II is a practical guide for starting QCC programs. It provides guidance for facilitators and circle leaders on carrying out daily QCC activities and solving common problems. The handbook aims to explain TQM and QCC at a level appropriate for different readers, from top managers to frontline employees.

![1 Quality Assurance in the 21st Century

1-1-2 Quality Management in a Changing World

Across nations and regions, companies are facing new challenges in a

changing environment. First, the integration of world markets has been

rapidly proceeding. With open market economies in many parts of the world,

overseas production has been accelerated ─ goods can now be produced

anywhere in the world where the cost of production is the cheapest. Such

globalization of markets has affected not only exporters and importers but

also domestic players, even small companies, in many ways: price

competition has become tougher, product diversification is in higher demand,

safety and reliability of goods have become indispensable, higher standards

of quality in developed countries are also being applied to markets in

developing countries, and so on.

A second challenge to providers of goods and services is that their

stakeholder base has been substantially broadened, and consequently, their

social responsibilities have enlarged. The requirement for environmental

consideration is a typical example. Another one, product liability legislation,

has become prevalent in many economies, making goods and service

providers much more accountable for their work than they were a decade ago.

Third is an increasing need for companies to focus on accountability and

transparency of management in order to demonstrate good risk management.

The chance that a company could have its reputation damaged overnight has

increased, because society today has a highly developed information network

that can easily proliferate public mistrust. In fact, examples of foul play by

renowned companies, both domestic and international, can be found easily

(e.g., Firestone Bridgestone [U.S., 2000], Mitsubishi Motors [Japan, 2000],

Snow Brand [Japan, 2002], Nippon Ham [Japan, 2002]). Companies have

been forced to retreat from the market or at least temporarily set back

because of fraud.

Fourth is a proliferation of complications related to customer satisfaction.

Customer needs continue to evolve in line with the diversification of lifestyles,

and high quality and functionality are expected of every product. With

information technology far developed compared to a decade ago, availing

much more product information, customers are demanding more real value

in products. In addition to price and usability, factors such as fashion and

uniqueness are involved. World markets being more integrated, consumers

now have a wider selection of goods and services with which to satisfy their

appetites.

Overall, the current business environment has become much more complex,

and elements concerning quality of products and services that were not

considered as crucial for business success a decade ago, now are. As noted

earlier, TQM provides a powerful platform on which companies apply quality

management not only at the production or service delivery levels, but also on

a company-wide scale. Therefore, TQM’s potential needs to be exhausted

more completely than it ever has. At the same time, the TQM concept will

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handbook-for-tqm-qcc-1-100717101128-phpapp02/85/Handbook-for-tqm-qcc-1-18-320.jpg)

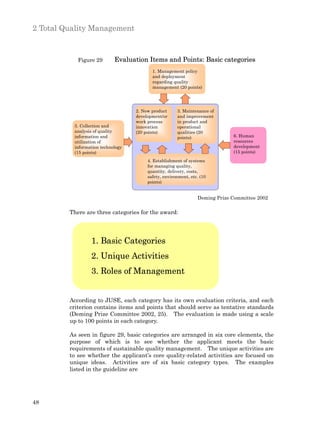

![2 Total Quality Management

management. At the same time, it aims to publicize organizations’

successful business performance and disseminate the business management

ideas of the awarded companies. Now the award is the “highest honor for

performance excellence, and it is presented annually to U.S. organizations by

the President of the United States” (the National Institute of Standards and

Technology [NIST] homepage).

Winners of the award in 2001 were

n Clarke American Checks, Incorporated (manufacturing)

n Pal’s Sudden Service (small business)

n Chugach School District (Education)

n Pearl River School District (Education)

n University of Wisconsin-Stout (Education)

In the past, companies like IBM Rochester, Xerox Corp., and Merrill Lynch

Credit Corp. have also won the award.

The award originated in circumstances in which American industry

competitiveness in the world market was declining due to deficiencies in

quality and productivity. U.S. industry’s long history of dominance in the

world market had made it less sensitive to the outside market, and caused it

to neglect the development of new technology, which resulted in a lack of

policy strategy in production management. Beginning in the late 1970s, its

dominance in world markets, particularly in manufacturing industries, such

as automobile, textile, and semiconductor, was overridden by Japanese

products. Massachusetts Institute of Technology established a committee

on productivity and initiated its own research aimed to examine deficiency in

American productivity and find a potential strategy for quality control

(Mikata 1995, 80). The two-year research revealed the following conclusions

about U.S. industry in its final report.

n Outdated management strategy

n Short-term perspective

n Lack of technology in research and production

n Neglected human resources

n Lack of cooperative structure within the organization

(Mikata 1995, 80)

The research group also proposed a list of successful elements and efforts

commonly seen in well performing companies. The cause of backward

productivity was often explained by environmental factors, such as

macroeconomic issues, yet these elements had pointed out that much effort

was needed in management of the companies themselves.

The key elements identified were improvement in quality, cost and time of

delivery; assurance of customer needs; relationship with suppliers; effective

usage of technology for strategic management; decentralization of the

stratum of organization so as to correspond to the management trend; and

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/handbook-for-tqm-qcc-1-100717101128-phpapp02/85/Handbook-for-tqm-qcc-1-64-320.jpg)